Meningitis and Effects on Epilepsy: Difference between revisions

| Line 48: | Line 48: | ||

Revision as of 23:46, 18 April 2022

Introduction

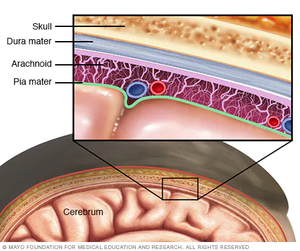

Meningitis is an infection that results in the swelling of the meninges (membranes) and fluid of the spinal cord and back.[1] Severity of acute infection can vary from person to person. In some cases, the bacteria die off on their own and the infection fades away after a few weeks. In other cases of meningitis, immediate hospitalization is required with the treatment of IV antibiotics. [2] However, the severity of a person’s meningitis case can vary with the mode of infection as well. There are as many as 6 different ways to contract meningitis but the most common ways are through a virus, fungus, and bacteria. Fungal infections of meningitis are rarer and fungal and viral infections cause fewer complications and are easier to treat.[3] As always, younger and immune-compromised persons have a higher risk of serious complications with this infection. Unfortunately, not all symptoms and side effects of this disease are short-term. Long-term neurological issues such as learning disabilities, narcolepsy, and even epilepsy are being discovered and researched.

Epilepsy, also known as the “chronic seizure disorder”, is exactly what the name implies. It is a disorder that is characterized by a person experiencing unprompted and reoccurring seizures.[4] Many affected people will experience a variety of seizures including but not limited to tonic, clonic, and absence. Tonic seizures are when the muscles in the body freeze up and become stiff, clonic seizures are characterized by uncontrolled jerking movements, and absence seizures are lapses in a person’s awareness or consciousness for short periods of time. When combined together, Tonic-Clonic seizures are also called Grand Mal.[5][6] Epilepsy is known to have several different causes such as genetic abnormalities, brain injury, and defects in development. However, recent studies show that brain infections, such as meningitis, are becoming a much more prevalent cause of epilepsy.[7]

Continued research into this growing field of long-lasting effects of brain infections has furthered the understanding of their effects on different parts of the brain, including those that affect epilepsy. The link between these two health problems is becoming increasingly more clear as linked cases continue to rise every day. Current information suggests and proves that meningitis patients have an increased risk of developing epilepsy than those who have not contracted meningitis.[8]

Viral Meningitis

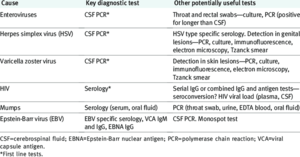

Viral meningitis is the most common form. It is most often caused by non-polio enteroviruses. These can include mumps, Epstein-Barr, influenza, measles, and others. Fortunately, only a small number of those infected with any of the above viruses will contract meningitis as a result. The contagion of viral meningitis is determined by the contagion of the virus causing meningitis. However, before current medications and vaccines, once contracted, there was a 30-40% chance of developing meningitis from any of the above viruses. Now, here is only a 5-10% chance (varies by virus).[9]

While common symptoms can vary based on age, there are similarities in patients of all age groups. These are fever, headache, poor appetite, photophobia, sleepiness, vomiting, and lethargy. As with most viral infections, there is no specific treatment such as antibiotics. If someone is seriously ill and needs to be admitted to the hospital, they will most likely have their symptoms treated and monitored.[10]

Bacterial Meningitis

Bacterial meningitis is the second most prevalent form of meningitis. It is also the most deadly form. It is fact acting and can cause serious paint throughout the entire experience. Some who contract this are unlucky enough to be affected for a few weeks while others pass within a few hours of contraction.

Just like viral meningitis, there are multiple different pathogens that can cause the bacterial form such as Streptococcus pneumoniae, Group B Streptococcus, Neisseria meningitidis, Haemophilus influenzae, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis.[11] Group B Streptococcus can be spread mother to child during birth or breastfeeding. Streptococcus pneumoniae, Neisseria meningitidis, Haemophilus influenzae, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis are spread through physical contact with body fluids such as spit or by breathing in the pathogens. E. Coli can even cause bacterial meningitis when contracted from a food source.[12]

The signs and symptoms are similar if not identical to viral meningitis but the treatment is different. For bacterial meningitis, IV antibiotics are a possibility. Most patients are also given steroids for brain swelling, oxygen in case of lung complications, and other IV fluids for dehydration.

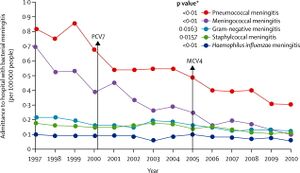

There are vaccines as well to prevent the spread and contraction before it begins. In the late 1990s to early 2000s, the rate of death from meningitis was almost 30% and the hospitalization rate was as high as 90% for some original pathogens. It is now down to about 10% for the death rate and an average of 30% for hospitalization.[13]

Fungal Meningitis

Include some current research, with at least one figure showing data.

Neisseria meningitidis and its Genome

What Meningitis does to the Brain

Epilepsy

How Meningitis causes Epilepsy

References

- ↑ [1] “Meningitis.” Mayo Clinic, Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research, 1 Oct. 2020

- ↑ [2] "Meningitis: Symptoms, Causes, Transmission, and Treatment.” WebMD, WebMD

- ↑ [3] “Meningitis.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 30 Mar. 2022

- ↑ [https://www.epilepsy.com/learn/about-epilepsy-basics/what-epilepsy ]“What Is Epilepsy? Disease or Disorder?” Epilepsy Foundation, 21 Jan. 2014

- ↑ [4]“Types of Seizures.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 30 Sept. 2020.

- ↑ [5]“Absence Seizure.” Mayo Clinic, Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research, 24 Feb. 2021.

- ↑ [6]“Epilepsy.” Mayo Clinic, Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research, 7 Oct. 2021.

- ↑ [7]Vezzani, Annamaria, et al. “Infections, Inflammation and Epilepsy.” Acta Neuropathologica, U.S. National Library of Medicine, Feb. 2016.

- ↑ [8]“Viral Meningitis.” Mayo Clinic, Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research, 1 Oct. 2020.

- ↑ [9]“Meningitis from Viruses.” Meningitis Now.

- ↑ [10]“Bacterial Meningitis.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 15 July 2021.

- ↑ [11] “Bacterial Meningitis: Causes, Symptoms, Treatment & Prevention.” Cleveland Clinic.

- ↑ https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/meningitis/treatment/] “Bacterial Meningitis.” NHS Choices.

Authored for BIOL 238 Microbiology, taught by Joan Slonczewski, 2022, Kenyon College