Histoplasma capsulatum: Difference between revisions

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

[[Image:HC37C.jpg|350px|right|Yeast phase from a culture at 37°C on Kurung medium (Unstained)]] | [[Image:HC37C.jpg|350px|right|Yeast phase from a culture at 37°C on Kurung medium (Unstained)]] | ||

Histoplasma capsulatum is a biologically interesting inhabitant of soil and mammalian hosts, a clinically significant cause of respiratory and systemic infection, and an excellent fungal model of dimorphic cell development and facultative intracellular pathogenesis. [4] H. capsulatum is unique in its dimorphism. Dimorphism allows H. capsulatum to infect mammals by going through three significant development stages depends on the temperature shift from 25 °C to 37 °C. [1, 12] In the soil when the temperature is about 25 °C, H. capsulatum exists in a filamentous mycelia form. It thrives in moist rich soil in temperate climates and is particularly closely associated with soil containing bird or bat guano. [4] However, when humans inhale H. capsulatum into their respiratory tracks, in order to replicate its DNA in the host at 37C, the pathogen has to be able to convert it’s tissue from one form to another. In this case, H. Capsulatum changed from fungi to yeast when it’s growing in the human bodies. [5, 16] H. capsulatum is thought to cause approximately 500,000 respiratory infections a year in the central river valleys in the Midwestern and south central United States. [2, 7] | Histoplasma capsulatum is a biologically interesting inhabitant of soil and mammalian hosts, a clinically significant cause of respiratory and systemic infection, and an excellent fungal model of dimorphic cell development and facultative intracellular pathogenesis. [4] H. capsulatum is unique in its dimorphism. Dimorphism allows H. capsulatum to infect mammals by going through three significant development stages depends on the temperature shift from 25 °C to 37 °C. [1, 12] In the soil when the temperature is about 25 °C, H. capsulatum exists in a filamentous mycelia form. It thrives in moist rich soil in temperate climates and is particularly closely associated with soil containing bird or bat guano. [4] However, when humans inhale H. capsulatum into their respiratory tracks, in order to replicate its DNA in the host at 37C, the pathogen has to be able to convert it’s tissue from one form to another. In this case, H. Capsulatum changed from fungi to yeast when it’s growing in the human bodies. [5, 16] H. capsulatum is thought to cause approximately 500,000 respiratory infections a year in the central river valleys in the Midwestern and south central United States. [2, 7] | ||

Revision as of 02:38, 27 August 2007

A Microbial Biorealm page on the genus Histoplasma capsulatum

Classification

Higher order taxa

Cellular Organisms; Eukaryota (Superkingdom); Fungi (Kingdom); Dikarya (Subkingdom); Ascomycota (Phylum); Pezizomycotina (Subphylum); Eurotiomycetes (Class); Eurotiomycetidae (Subclass); Onygenales (Order); Ajellomycetaceae (Family); Ajellomyces (Genus) [16]

Species

Species: Ajellomyces capsulata

Anamorph (an asexal reproductive stage): Histoplasma capsulatum [5]

Description and significance

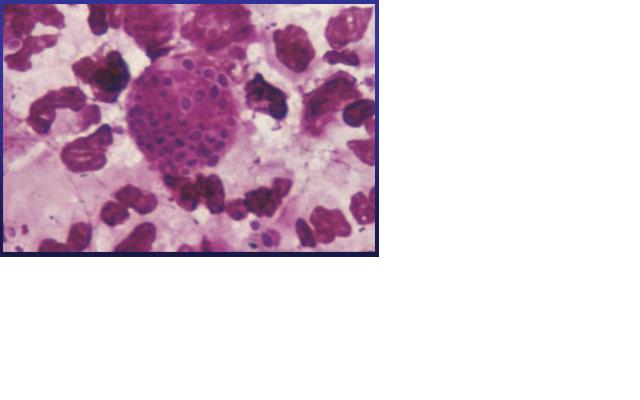

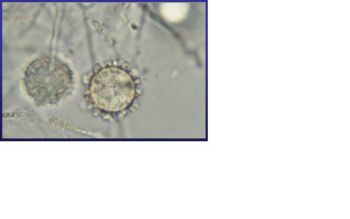

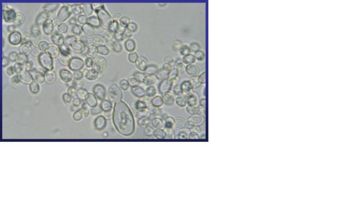

Histoplasma capsulatum is a biologically interesting inhabitant of soil and mammalian hosts, a clinically significant cause of respiratory and systemic infection, and an excellent fungal model of dimorphic cell development and facultative intracellular pathogenesis. [4] H. capsulatum is unique in its dimorphism. Dimorphism allows H. capsulatum to infect mammals by going through three significant development stages depends on the temperature shift from 25 °C to 37 °C. [1, 12] In the soil when the temperature is about 25 °C, H. capsulatum exists in a filamentous mycelia form. It thrives in moist rich soil in temperate climates and is particularly closely associated with soil containing bird or bat guano. [4] However, when humans inhale H. capsulatum into their respiratory tracks, in order to replicate its DNA in the host at 37C, the pathogen has to be able to convert it’s tissue from one form to another. In this case, H. Capsulatum changed from fungi to yeast when it’s growing in the human bodies. [5, 16] H. capsulatum is thought to cause approximately 500,000 respiratory infections a year in the central river valleys in the Midwestern and south central United States. [2, 7]

Histoplasma capsulatum reproduce occurring in the mold form of the fungus and is heterothallic. H. capsulatum is the anamorphic classification, while the teleomorph or perfect form is known as Ajellomyces capsulatus. Many approaches have been used to differentiate H. capsulatum strains. Three variants have been described based on host predilection, clinical presentation, geographic distribution, or serology: variant duboisii in Africa, variant farciminosum in horses, and variant capsulatum for the mijority isolates. [4, 5] The structure of H. capsulatum has not yet been studied with detail. There have been studies that focused on the polysaccharides composition of the cell walls. [5] The genome of H. capsulatum has also not yet been totally sequenced; however, certain strains of DNA have been studied. For examples, the G217B, G186A, and the Downs strain. [5] Many of the research centers are currently focusing on constructing the genome of H. capsulatum, such as University of Washington School of Medicine, and the Broad Institute. [8, 13] It will be useful to sequence the genome of H. capsulatum, because it can help answering many biological questions that scientists have. For example, the capacity to undergo the morphologic transition to the yeast phase, the different genes code for different functions necessary for survival, and the phase specific genes regulation. [1]

Genome structure

Describe the size and content of the genome. How many chromosomes? Circular or linear? Other interesting features? What is known about its sequence? Does it have any plasmids? Are they important to the organism's lifestyle?

Cell structure and metabolism

Describe any interesting features and/or cell structures; how it gains energy; what important molecules it produces.

Ecology

Describe any interactions with other organisms (included eukaryotes), contributions to the environment, effect on environment, etc.

Pathology

How does this organism cause disease? Human, animal, plant hosts? Virulence factors, as well as patient symptoms.

Application to Biotechnology

Does this organism produce any useful compounds or enzymes? What are they and how are they used?

Current Research

Enter summaries of the most recent research here--at least three required

References

1. Bossche, Hugo, Frank Odds, and David Kerridge. Dimorphic Fungi in Biology and Medicine. 1st ed. New York and London: Plenum Press, 1993

2. Chang, Ryan. "Histoplasmosis." 19 Sep 2005. emedicine. 25 Aug 2007 <http://www.emedicine.com/MED/topic1021.htm>.

3. Hayward, Chris A. "Microorganisms." Encyclopedia of Life Sciences 20062006 1-13. <http://www.mrw.interscience.wiley.com/emrw/9780470015902/els/article/a0000460/current/pdf>.

4. Heitman, Joseph, Scott G. Filler, Aaron P. Mitchell, and John E. Edwards, Jr.Molecular Principles of Fungal Pathogenesis. 1st ed. New York: ASM Press, 2006. (Heitman et al. 321-331)

5. Heitman, Joseph, Scott G. Filler, Aaron P. Mitchell, and John E. Edwards, Jr.Molecular Principles of Fungal Pathogenesis. 1st ed. New York: ASM Press, 2006. (Heitman et al. 611-626)

6. "Histoplasmosis." Histoplasmosis Resource Guide. Mar 2007. National Eye Institute. 25 Aug 2007 <http://www.nei.nih.gov/health/histoplasmosis/index.asp>.

7. "Histoplasmosis." Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 12 Oct 2005. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 25 Aug 2007 <http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dbmd/diseaseinfo/histoplasmosis_g.htm>.

8. Hwang, Lena, Davina Hocking-Murray, Adam K. Bahrami, Margareta Andersson, and Jasper Rine. "Identifying Phase-specific Genes in the Fungal Pathogen Histoplasma capsulatum Using Genomic Shotgun Microarray." Molecular Biology of the Cell June 2003 2314-2326. .

9. Johnson, Clayton, Jonathan T. Prigge, Aaron D. Warren, and Joan E. McEwen. "Characterization of an alternative oxidase activity of Histoplasma Capsulatum." Yeast 2003 381-388. .

10. Kendrick, Bryce. "Fungi: Ecological Importane and Impact on Humans." Encyclopedia of Life Sciences 20012001 1-5. <http://www.mrw.interscience.wiley.com/emrw/9780470015902/els/article/a0000369/current/pdf>.

11. Kobayashi, George S. "Mycoses." Encyclopedia of Life Sciences 20012001 1-6. <http://www.mrw.interscience.wiley.com/emrw/9780470015902/els/article/a0000371/current/pdf>.

12. Kobayashi, George S.. "Molecular Basis of Adaptation in Histoplasma capsulatum ." Washington University School of Medicine. 25 Aug 2007 <http://research.medicine.wustl.edu/OCFR/Research.nsf/Abstracts/64ABA9996B650C50862567ED00029E69?OpenDocument&VW=Infectious+Diseases>.

13. Lai, Chung-Hsu, Chun-Kai Huang, Chuen Chin, Ya-Ting Yang, and Hsiu-Fang Lin. "Indigenous Case of Disseminated Histoplasmosis, Taiwan." Emerging Infectious Diseases Jan 2007 127-129. .

14. Maubon, Daniele, Stephane Simon, and Christine Aznar. "Histoplasmosis diagnosis using a polymerase chain reaction method. Application on human samples in French Guiana, South America." 04 Aug 2007

15. Mitchell, Thomas G. "Fungal Pathogens of Human." Encyclopedia of Life Science 20022002 1-15. <http://www.mrw.interscience.wiley.com/emrw/9780470015902/els/article/a0000359/current/pdf?hd=All%2Chistoplasma&hd=All%2Ccapsulatum>.

16. National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Taxonomy Browser. Taxonomy ID:5037

17. Nittler, M.Paige, Davina Hocking-Murray, Catherine K. Foo, and Anita Sil. "Identification of Histoplasma capsulatum Transcripts Induced in Response to Reactive Nitrogen Species." Molecular Biology of the Cell Oct 2005 4792-4813. .

18. Rappleye, C. A., Eissenberg, L. G. & Goldman, W. E. Histoplasma capsulatum (1,3)-glucan blocks innate immune recognition by the -glucan receptor. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 23, 1366–1370 (2007)

Edited by Shen-Yin (Mandy) Hung of Rachel Larsen