Bifidobacterium adolescentis: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 47: | Line 47: | ||

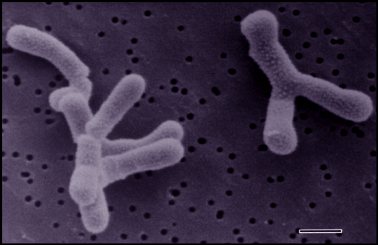

[[Image:bifidobacterium.jpg|frame|right|''Bifidobacterium adolescentis''. A helpful bacterium that is an inhabitant of the human intestinal tract. From [http://sci.agr.ca/crda/indust/microscope_e.htm The Food Research and Development Centre, Canada. Diane Montpetit]]] | [[Image:bifidobacterium.jpg|frame|right|''Bifidobacterium adolescentis''. A helpful bacterium that is an inhabitant of the human intestinal tract. From [http://sci.agr.ca/crda/indust/microscope_e.htm The Food Research and Development Centre, Canada. Diane Montpetit]]] | ||

''Bifidobacterium adolescentis'' are normal inhabitants of healthy human and animal intestinal tracts. Colonization of ''B. adolescentis'' in the gut occurs immediately after birth. Their population in the gut tends to maintain relative stability until late adulthood, where factors such as diet, stress, and antibiotics causes it to decline( | ''Bifidobacterium adolescentis'' are normal inhabitants of healthy human and animal intestinal tracts. Colonization of ''B. adolescentis'' in the gut occurs immediately after birth. Their population in the gut tends to maintain relative stability until late adulthood, where factors such as diet, stress, and antibiotics causes it to decline(2). This species was first isolated by Tissier in 1899 in the feces of breast-fed newborns. Tissier was the first to promote the therapeutic use of bifidobacteria for treating infant diarrhea by giving them large doses of bifidobacteria orally. Since then, their presence in the gut has been associated with a healthy microbiota (2,6). The correlation between the presence of bifidobacteria and gastrointestinal health has produced numerous studies focusing on gastrointestinal ecology and the health-promoting aspects that bifidobacteria are involved in. Obtaining more information about specific strains of bifidobacteria and their roles in the gastrointestinal tract have been on the rise as these probiotic organisms are being used as food additives, such as dairy products. Their name is derived from the observation that these bacteria often exist in a Y-shaped, or bifid form (2,4). | ||

There are currently 29 species of ''Bifidobacteria'' that have been described; Five of which, including ''B. adolescentis'' that have interested dairy manufacturers in producing "therapeutic fermented milk products" ( | There are currently 29 species of ''Bifidobacteria'' that have been described; Five of which, including ''B. adolescentis'' that have interested dairy manufacturers in producing "therapeutic fermented milk products" (2). | ||

| Line 55: | Line 55: | ||

Genome structure | Genome structure | ||

The genome of ''Bifidobacterium adolescentis'' averages 2.1 Mbp in length. Its form is either an elongated, thin irregular rod-, Y- or V-shape. ''B. adolescentis''contains one circular chromosome. ''B. adolescentis'' has 2,089,645 nucleotides, including 1,631 protein-encoding genes and 69 RNA genes ( | The genome of ''Bifidobacterium adolescentis'' averages 2.1 Mbp in length. Its form is either an elongated, thin irregular rod-, Y- or V-shape. ''B. adolescentis''contains one circular chromosome. ''B. adolescentis'' has 2,089,645 nucleotides, including 1,631 protein-encoding genes and 69 RNA genes (2). G-C content ranges from 42-67% (3), with an average range around 60% (2). To date, no plasmids have been detected in ''B. adolescentis''(7). | ||

| Line 62: | Line 62: | ||

Cell structure and metabolism | Cell structure and metabolism | ||

''B. adolescentis'' is a gram-positive organism, containing one cell membrane, and is not mobile ( | ''B. adolescentis'' is a gram-positive organism, containing one cell membrane, and is not mobile (2,4). Each species of bifidobacteria contain different components in their cell walls; ''B. adolescentis''' cell wall is made made primarily of murein, containing Lys- or Orn-D-Asp within its peptide chains. Its polysaccharide components include glucose and galactose. Myristic, palmitic, and oleic are the major fatty acids within the cell wall. Leipoteichoic acids on the cell wall's surface function to help the organism adhere to the intestinal wall (1). | ||

Bifidobacteria are anaerobes (though some can tolerate oxygen, using enzymes superoxide dismutase and catalase in their defense against the toxic effects of superoxide and hydrogen peroxide)( | Bifidobacteria are anaerobes (though some can tolerate oxygen, using enzymes superoxide dismutase and catalase in their defense against the toxic effects of superoxide and hydrogen peroxide)(1). ''B. adolescentis'', like all of the Bifidobacteria species, can ferment lactose and grow well in milk, as well as use many carbohydrates. Glucose is fermented using the fructose-6-phosphate pathway which requires the enzyme, fructose-6-phosphoketolase(F6PPK)(1). As a result of metabolizing various carbohydrates, bifidobacteria produce short-chain fatty acids such as propionate, butyrate, and acetate to be used as energy sources (1). | ||

Nitrogen metabolism is also observed in bifidobacteria, using ammonium sulfate as its nitrogen source. As a result, bifidobacteria's ability to use ammonia as a nitrogen source may decrease that amount of ammonia in the colon( | Nitrogen metabolism is also observed in bifidobacteria, using ammonium sulfate as its nitrogen source. As a result, bifidobacteria's ability to use ammonia as a nitrogen source may decrease that amount of ammonia in the colon(1). | ||

Bifidobacteria have also been found to synthesize vitamins; ''B. adolescentis''predominantly synthesizes cyanocobalamin and nicotine, as well as thiamin, folic acid, and pyridoxine. ''B. adolescentis''' ability to produce vitamins plays a beneficial role in increasing the nutritional quality of fermented dairy products when added in ( | Bifidobacteria have also been found to synthesize vitamins; ''B. adolescentis''predominantly synthesizes cyanocobalamin and nicotine, as well as thiamin, folic acid, and pyridoxine. ''B. adolescentis''' ability to produce vitamins plays a beneficial role in increasing the nutritional quality of fermented dairy products when added in (1,8). | ||

| Line 73: | Line 73: | ||

Ecology | Ecology | ||

Bifidobacteria colonize and reside in the gastrointestinal tracts of humans as well as most mammals. Before birth, human fetuses are microbe-free, and thus do not contain in bacteria within their digestive tracts. However, almost immediately after birth, bacteria begin to colonize in the newborn's intestinal tract, forming the intestinal micrflora (1, | Bifidobacteria colonize and reside in the gastrointestinal tracts of humans as well as most mammals. Before birth, human fetuses are microbe-free, and thus do not contain in bacteria within their digestive tracts. However, almost immediately after birth, bacteria begin to colonize in the newborn's intestinal tract, forming the intestinal micrflora (1,2,10). While various bacteria make up the microflora, bifidobacteria predominate as the main bacteria during the neonatal period of development, especially in infants that are breast-fed. Bifidobacteria's predominance in the intestinal tract has been confirmed by its high percentage (96%) of the bacterial content within infant fecal matter samples.(10) | ||

As a resident within the human gut, bifidobacteria create a bacteria-host, symbiotic-like relationship, providing the human host with many health benefits( | As a resident within the human gut, bifidobacteria create a bacteria-host, symbiotic-like relationship, providing the human host with many health benefits(1,4,6). Healthful contributions by bifidobactia include improved intestinal functioning, by increasing the absorption of human milk protein by removing the casein in human milk. Improved amino acid metabolism is seen in bifidobacteria's production of various B vitamins. In infants, bifidobacteria play a significant role in preventing the loss of nutrients, by suppressing the growth of competing bacteria in the intestinal tract. Bifidobactia prevent constipation in the host by producing acids that stimulate peristalsis and promote normal bowel movements. This contribution is reinforced by the availability of Bifidus preparations for constipation sufferers, which work by moistening fecal material. Antibiotic activity is also carried by bifidobacteria, working against pathogens such as ''E.coli'', ''Staphylococcus aureus'', ''Shigella dysenteriae'', ''Salmonella typhi'', ''Proteus ssp.'', and ''Candida albicans'' by supressing their growth. | ||

Describe any interactions with other organisms (included eukaryotes), contributions to the environment, effect on environment, etc. | Describe any interactions with other organisms (included eukaryotes), contributions to the environment, effect on environment, etc. | ||

| Line 108: | Line 108: | ||

References | References | ||

1.[ | 1.[Arunachalam, Kantha D., et al. ''The Role of Bifidobacteria in Nutrition, Medicine, and Technology''. Nutrition Research. Vol 19, No. 10, pp. 1559-1597, 1999. Elsevier Science Inc., USA.] | ||

2.[Biavati, B. and Mattarelli, P. (2001) The family Bifidobacteriaceae. In: The Prokaryotes (Dworkin, M., Falkow, S., Rosenberg, | 2.[http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?db=genomeprj&cmd=Retrieve&dopt=Overview&list_uids=16321 Genome Project: ''Bifidobacterium adolescentis ATCC 15703'' project at Gifu University, Life Science Research Center, Japan/NCBI, Bethesda, USA] | ||

3.[Biavati, B. and Mattarelli, P. (2001) The family Bifidobacteriaceae. In: The Prokaryotes (Dworkin, M., Falkow, S., Rosenberg, | |||

E., Schleifer, K.H. and Stackebrandt, E., Eds.), pp. 1–70. Springer, New York.] | E., Schleifer, K.H. and Stackebrandt, E., Eds.), pp. 1–70. Springer, New York.] | ||

4.[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bifidobacterium ''Bifidobacterium''] (Wikipedia) | |||

5.[http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/doi/pdf/10.1016/j.femsle.2005.05.008 Haros, Monica. ''Phytase activity as a novel metabolic feature in Bifidobacterium''. FEMS Microbiology Letters 247, 2005, pp.231–239.] | 5.[http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/doi/pdf/10.1016/j.femsle.2005.05.008 Haros, Monica. ''Phytase activity as a novel metabolic feature in Bifidobacterium''. FEMS Microbiology Letters 247, 2005, pp.231–239.] | ||

Revision as of 06:51, 4 June 2007

Bifidobacterium adolescentis

From MicrobeWiki, the student-edited microbiology resource

Jump to: navigation, search

Contents [hide]

* 1 Classification

o 1.1 Higher order taxa

o 1.2 Genus

* 2 Description and significance

* 3 Genome structure

* 4 Cell structure and metabolism

* 5 Ecology

* 6 Pathology

* 7 Application to Biotechnology

* 8 Current Research

* 9 References

[edit]

Classification

[edit]

Higher order taxa

Bacteria; Actinobacteria; Actinobacteridae; Bifidobacteriales; Bifidobacteriaceae; Bifidobacterium; Bifidobacterium adolescentis ATCC 15703

[edit]

Genus

Bifidobacterium adolesecentis

Species

B. angulatum; B. animalis; B. asteroides; B. bifidum; B. boum; B. breve; B. catenulatum; B. choerinum; B. coryneforme; B. cuniculi; B. dentium; B. gallicum; B. gallinarum; B indicum; B. longum; B. magnum; B. merycicum; B. minimum; B. pseudocatenulatum; B. pseudolongum; B. psychraerophilum; B. pullorum; B. ruminantium; B. saeculare; B. scardovii; B. simiae; B. subtile; B. thermacidophilum; B. thermophilum; B. urinalis; B. sp.

NCBI: Taxonomy

[edit]

Description and significance

Bifidobacterium adolescentis are normal inhabitants of healthy human and animal intestinal tracts. Colonization of B. adolescentis in the gut occurs immediately after birth. Their population in the gut tends to maintain relative stability until late adulthood, where factors such as diet, stress, and antibiotics causes it to decline(2). This species was first isolated by Tissier in 1899 in the feces of breast-fed newborns. Tissier was the first to promote the therapeutic use of bifidobacteria for treating infant diarrhea by giving them large doses of bifidobacteria orally. Since then, their presence in the gut has been associated with a healthy microbiota (2,6). The correlation between the presence of bifidobacteria and gastrointestinal health has produced numerous studies focusing on gastrointestinal ecology and the health-promoting aspects that bifidobacteria are involved in. Obtaining more information about specific strains of bifidobacteria and their roles in the gastrointestinal tract have been on the rise as these probiotic organisms are being used as food additives, such as dairy products. Their name is derived from the observation that these bacteria often exist in a Y-shaped, or bifid form (2,4).

There are currently 29 species of Bifidobacteria that have been described; Five of which, including B. adolescentis that have interested dairy manufacturers in producing "therapeutic fermented milk products" (2).

[edit]

Genome structure

The genome of Bifidobacterium adolescentis averages 2.1 Mbp in length. Its form is either an elongated, thin irregular rod-, Y- or V-shape. B. adolescentiscontains one circular chromosome. B. adolescentis has 2,089,645 nucleotides, including 1,631 protein-encoding genes and 69 RNA genes (2). G-C content ranges from 42-67% (3), with an average range around 60% (2). To date, no plasmids have been detected in B. adolescentis(7).

[edit] Cell structure and metabolism

B. adolescentis is a gram-positive organism, containing one cell membrane, and is not mobile (2,4). Each species of bifidobacteria contain different components in their cell walls; B. adolescentis' cell wall is made made primarily of murein, containing Lys- or Orn-D-Asp within its peptide chains. Its polysaccharide components include glucose and galactose. Myristic, palmitic, and oleic are the major fatty acids within the cell wall. Leipoteichoic acids on the cell wall's surface function to help the organism adhere to the intestinal wall (1). Bifidobacteria are anaerobes (though some can tolerate oxygen, using enzymes superoxide dismutase and catalase in their defense against the toxic effects of superoxide and hydrogen peroxide)(1). B. adolescentis, like all of the Bifidobacteria species, can ferment lactose and grow well in milk, as well as use many carbohydrates. Glucose is fermented using the fructose-6-phosphate pathway which requires the enzyme, fructose-6-phosphoketolase(F6PPK)(1). As a result of metabolizing various carbohydrates, bifidobacteria produce short-chain fatty acids such as propionate, butyrate, and acetate to be used as energy sources (1).

Nitrogen metabolism is also observed in bifidobacteria, using ammonium sulfate as its nitrogen source. As a result, bifidobacteria's ability to use ammonia as a nitrogen source may decrease that amount of ammonia in the colon(1).

Bifidobacteria have also been found to synthesize vitamins; B. adolescentispredominantly synthesizes cyanocobalamin and nicotine, as well as thiamin, folic acid, and pyridoxine. B. adolescentis' ability to produce vitamins plays a beneficial role in increasing the nutritional quality of fermented dairy products when added in (1,8).

[edit]

Ecology

Bifidobacteria colonize and reside in the gastrointestinal tracts of humans as well as most mammals. Before birth, human fetuses are microbe-free, and thus do not contain in bacteria within their digestive tracts. However, almost immediately after birth, bacteria begin to colonize in the newborn's intestinal tract, forming the intestinal micrflora (1,2,10). While various bacteria make up the microflora, bifidobacteria predominate as the main bacteria during the neonatal period of development, especially in infants that are breast-fed. Bifidobacteria's predominance in the intestinal tract has been confirmed by its high percentage (96%) of the bacterial content within infant fecal matter samples.(10)

As a resident within the human gut, bifidobacteria create a bacteria-host, symbiotic-like relationship, providing the human host with many health benefits(1,4,6). Healthful contributions by bifidobactia include improved intestinal functioning, by increasing the absorption of human milk protein by removing the casein in human milk. Improved amino acid metabolism is seen in bifidobacteria's production of various B vitamins. In infants, bifidobacteria play a significant role in preventing the loss of nutrients, by suppressing the growth of competing bacteria in the intestinal tract. Bifidobactia prevent constipation in the host by producing acids that stimulate peristalsis and promote normal bowel movements. This contribution is reinforced by the availability of Bifidus preparations for constipation sufferers, which work by moistening fecal material. Antibiotic activity is also carried by bifidobacteria, working against pathogens such as E.coli, Staphylococcus aureus, Shigella dysenteriae, Salmonella typhi, Proteus ssp., and Candida albicans by supressing their growth.

Describe any interactions with other organisms (included eukaryotes), contributions to the environment, effect on environment, etc.

[edit]

Pathology

Bifidobacterium adolescentis is a non-pathogenic organism (1).

[edit]

Application to Biotechnology

B. adolescentis synthesizes various B vitamins that are beneficial to the nutritional health of the host organism. Vitamins that are synthesized included thiamin(B1), pyridoxine(B6), folic acid(B9), nicotine, cyanocobalamin(B12), ascorbic acid(Vitamin C), Biotin, and Riboflavin (4).

Also, bifidobacteria contain phytase activity, enabling the dephosphorylation of phytic acid (myo-inositol hexaphosphate, IP6) and produce several myo-inositol phosphate intermediates, IP3, IP4, and IP5. IP6 has been shown to have antinutritional effects by limiting the dietary bioavailability of amino acids and minerals such as Ca2+, Z2+, and Fe2+. However, bifidobacteria reduce these effects by dephosphorylating IP6 into lower phosphorylated products during food processing and gastrointestinal transit. Additionally, these lower phosphorylated intermediates are also involved in regulating vital cellular functions (5).

[edit]

Current Research

1. Bifidobacterium adolescentis as a producer of folate in the colon: testing various strains of Bifidobacterium revealed their ability to produce folate. Experiments analyzing cultured samples of feces showed that the addition of B. adolescentis may increase the folate concentration in a colonic environment. Results provided positive insight into the use of probiotics in preventing folate deficiency in colonic epithelial cells as well as more efficiently protecting the colon against inflammation and cancer(8).

2. Dietary Factors in inflammatory disease: (9).

3.

[edit] References

1.[Arunachalam, Kantha D., et al. The Role of Bifidobacteria in Nutrition, Medicine, and Technology. Nutrition Research. Vol 19, No. 10, pp. 1559-1597, 1999. Elsevier Science Inc., USA.]

3.[Biavati, B. and Mattarelli, P. (2001) The family Bifidobacteriaceae. In: The Prokaryotes (Dworkin, M., Falkow, S., Rosenberg, E., Schleifer, K.H. and Stackebrandt, E., Eds.), pp. 1–70. Springer, New York.]

4.Bifidobacterium (Wikipedia)

7.[http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=1352255 Lee, Ju-Hoon, and Sullivan, Daniel. Sequence Analysis of Two Cryptic Plasmids from Bifidobacterium longum DJO10A and Construction of a Shuttle Cloning Vector. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006 January; 72(1): 527–535. Copyright © 2006, American Society for Microbiology]

10.[Yaeshima T., et al. Bifidobacteria: their significance in human intestinal health. Malaysian Journal of Nutrition 3: 149-159, 1997. Morinaga Milk Industry Co. Ltd., Nutritional Science Laboratory, Japan.]

Edited by student of Rachel Larsen and Kit Pogliano