Canine parvovirus strain 2 (CPV-2)

Classification

Virus/Parvoviridae/Parvovirinae

Parvovirus feline panleukopenia virus (Canine parvovirus strain 2)

]

Description and Significance

Canine parvovirus strain 2 (CPV2) is the causative agent of "Parvo", an extremely virulent and contagious illness. CPV2 is the most significant viral infection of puppies in the United States. [2] Parvo is well controlled in the United States through the use of the parvovirus vaccine recommended for all dogs starting between the ages of 6-8 weeks and continued for the duration of their lives. CPV2 is almost identical to feline panleukopenia virus and only differs by two amino acids in the viral capsid and this small difference causes the virus to almost exclusively affect canines.

Structure, Metabolism, and Life Cycle

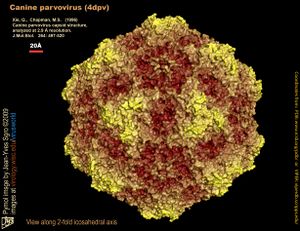

CPV2 is a non-enveloped, single-stranded DNA virus. It has a symmetrical icosahedral capsid enclosing a genome about 5000 nucleotides long. CPV2 enters the host cell via endocytosis, moves to the nucleus of the cell, and its genome is replicated by utilizing the host DNA polymerase. The viral DNA is then transcribed into mRNA and translated into viral capsid proteins by the host ribosomes. The viral genome is inserted into each capsid to form a virion and CPV2 virions leave the host cell by budding and are free to infect new host cells. [5]

Ecology and Pathogenesis

CPV2 can be found in the feces of infected dogs and can survive for up to two months indoors at room temperature, and persists for up to five months outdoors. Canine parvovirus targets the cells of the small intestine, lymph nodes and bone marrow, causing necrosis of the intestines and depletion of lymphocytes. Clinical symptoms that are associated with CPV2 infection are lethargy, vomiting fever and bloody diarrhea. These common symptoms can lead to dehydration and secondary infection. Necrosis of the intestines can cause protein and blood to leak into the the intestines causing anemia and endotoxemia. If the infection goes untreated, these complications can lead to shock or death. [4]]]

References

[1] Prittie, Jennifer (September 2004). "Canine Parvoviral Enteritis: A Review of Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention". J Vet Emerg Crit Care. 14 (3): 167–176. doi:10.1111/j.1534-6935.2004.04020.x.

[2] Kapil, S. (2007). "Canine Parvovirus Types 2c and 2b Circulating in North American Dogs in 2006 and 2007", Journal of clinical microbiology. 45(12), 4044-4047. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01300-07

[3] virology.wisc.edu/virusworld

[4] Mitchell, K, ed. "Canine Parvovirus: Diseases of the Stomach and Intestines in Small Animals." The Merck Veterinary Manual. The Merck Veterinary Manual, n.d. Web. 22 Jul 2013. <http://www.merckmanuals.com/vet/digestive_system/diseases_of_the_stomach_and_intestines_in_small_animals/canine_parvovirus.html?qt=canine parvovirus&alt=sh

[5] Truyen U (2006). "Evolution of canine parvovirus--a need for new vaccines?". Vet. Microbiol. 117 (1): 9–13. doi:10.1016/j.vetmic.2006.04.003. PMID 16765539.

Author

Page authored by Brandon VanHee, student of Mandy Brosnahan, Instructor at the University of Minnesota-Twin Cities, MICB 3301/3303: Biology of Microorganisms.