Effects of Pathogen-Vector Interactions on the Transmission of Dengue Virus: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

[[File:AD enhancement figure.jpg|600px|thumb|center|Figure 3. Antibody-dependent enhancement of DENV infection. [2]]] | [[File:AD enhancement figure.jpg|600px|thumb|center|Figure 3. Antibody-dependent enhancement of DENV infection. [2]]] | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

The FcγR receptors are effect in controlling other pathogens but DENV has evolved to exploit this pathway. The FcγR receptor is not needed for DENV entry but does increase infectivity DENV and allows the virus display cell tropisms not seen in primary DENV infection. With more cells infected more viroins are produced leading to higher levels of viremia in the blood which is correlated with increased risk for DHF and DSS. | |||

increase infectivity of the virus in immune cells by increasing overall viral load within the patient which in turn increases the risk of | increase infectivity of the virus in immune cells by increasing overall viral load within the patient which in turn increases the risk of | ||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

Revision as of 06:25, 7 December 2010

Effects of Pathogen-Vector Interactions on the Transmission of Dengue Virus

A Viral Biorealm page on the family Effects of Pathogen-Vector Interactions on the Transmission of Dengue Virus

Dengue Virus

Group IV: ss(+)RNA virus

Family: Flaviviridae

Genus: Flavivirus

Dengue virus (DENV) is the causative agent of both classical dengue fever, and the more severe manifestations; dengue hemorrhage fever (DHF) and dengue shock syndrome (DSS)[3]. It is most commonly transmitted by the mosquito vector Aedes aegypti but can be transmitted by other members of the genus Aedes including Aedes albopictus (Figure 2)[4]. There are four different serotypes of dengue virus (DENV 1-4). Infection with one serotype affords life-long immunity to that serotype but only partial (heterologous) immunity to other serotypes for a short period of time post-infection. After initial protective immunity the risk of developing DHF or DSS upon reinfection strain from a different serotype increases.

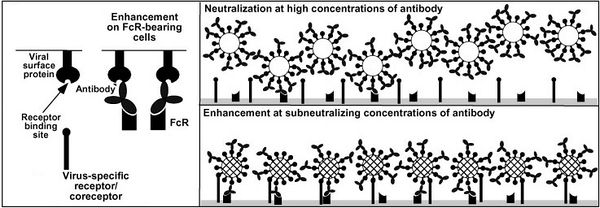

This increased risk for severe dengue is the result of antibody-dependent enhancement of viral infection. Host heterotypic non-neutralizing antibodies from previous DENV infection bind DENV virions. After recent DENV infection there are enough antibodies to neutralize any new dengue viruses but overtime the number of neutralizing antibodies drops. At some point there are so few enough antibodies left that upon reinfection with a new strain the anitbodies can bind but not nuetralize the virus. The constant region of the antibody can go on to bind a FcγR receptor on the surface of a number of different types of immune cells.Normally when a pathogen-antibody complex binds to a FcγR receptor a cytoxic or phagocytoic response initiated by the immunne cell. DENV somehow avoids this response and is brought close enough to its host cell receptor it can bind and infect the cell as seen in figure 3.

The FcγR receptors are effect in controlling other pathogens but DENV has evolved to exploit this pathway. The FcγR receptor is not needed for DENV entry but does increase infectivity DENV and allows the virus display cell tropisms not seen in primary DENV infection. With more cells infected more viroins are produced leading to higher levels of viremia in the blood which is correlated with increased risk for DHF and DSS.

increase infectivity of the virus in immune cells by increasing overall viral load within the patient which in turn increases the risk of

Within serotypes dengue viruses are organized by genotypes, then subtypes, then clades, variants, groups and finally strains [3]. The large number of dengue strains in the world combined with only partial crossover immunity to other strains makes concurrent (multiple strain) infections or reoccurring dengue infections possible (just like repeated bouts of the flu), especially in areas that have a high prevalence of dengue virus.

Dengue viruses are now endemic to tropical areas of the world putting about a third of the world’s population at risk of infection. There are estimated to be over one hundred million new infections per year and rising [4,5]. The rising rates of infection are the result of reduced vector control in areas that need it most and increased vector range. Global warming has made winters much milder at higher latitudes allowing adult and larvae mosquitoes to survive longer into the fall and return earlier in the spring. Dengue virus is becoming a threat to industrialized nations once thought to be too far away from the tropics for Dengue fever to be a threat. In the U.S. the number of indigenous dengue cases is rising. In Brownsville Texas, 25% of the residents who had never travelled outside the united states had antibodies indication prior exposure to the virus [discover article] [6].

The severity of dengue infection also continues to increase. The ratio of dengue hemorrhage fever and dengue shock syndrome cases to classical dengue fever have increased dramatically over the past sixty years. It has become the leading cause of hospitalization and death in children in several endemic countries [6].