Infectious Myositis

Overview

By [Chris Santucci]

Infectious Myositis is an infection that can be caused by microbes of all domains. It is characterized by muscle inflammation and usually is seen in voluntary muscle. [1] It is an uncommon infection and is very diverse in the way it can come about. Infectious myositis can result from surgeries in which incisions allow microbes in, wounds that are contaminated, injectable drug needles that are unsterilized, undercooked foods, among other reasons, making it difficult to detect and prevent at first. Immunocompromised individuals are always at risk for myositis. Myositis is not caused by one microbial group, but rather can be caused by a broad range of microbes including bacteria, fungi, viruses, and parasites. The infection can be polymicrobial, but in many cases one organism dominates the infected site. In order to identify the specific microbe responsible, culturing is necessary. This page hopes to express the vast array of infection and treatments associated with the main types of myositis.

To the right is a photograph depicting a patient with myositis of the gastrocnemius (Figure 1). This is a typical case of myositis in voluntary skeletal muscle.

Bacterial Infectious Myositis

Bacteria are the most common domain that can infect muscle leading to myositis from infection according to the literature. Staphylococcus aereus and Streptococcus strains, both gram-positive and typically facultative anaerobes, are the most common bacteria causing agents of myositis and are categorized into their own type of myositis. Some cases of bacterial myositis are polymicrobial, especially when infections are contaminated with soil. In events of bacterial myositis, it is necessary to culture on differential media and use gram staining to determine the bacteria responsible for the infection in order to treat the infection. Pyomyositis, psoas abscess, S. aereus myositis, group A and group B streptococcal myositis, Clostridial gas gangrene, and nonclostridial myositis are the distinctive categories of bacterial myositis. [2]

Pyomyositis

Pyomyositis, also known as tropical myositis because it is found often in tropical climates, is a bacterial infection due to hematogenous spread (spread through the blood stream) mainly caused by Staphylococcus aereus that is only present in one muscle group. [3]. This infection is often seen in children, but not always. [4] In fact, it can be found in people of all ages and is becoming more prevalent in the United States in the past 40 years. [5]

It was discovered that immunocompromised individuals, such as those with HIV, are more likely to acquire pyomyositis. [6] This can be attributed to many reasons, but most importantly the fact that S. aureus grows much more easily in immunocompromised people that have a weaker defense mechanism. [7] Pyomyositis cases, in general, have increased since the HIV epidemic has broken out. [8]

Some particular studies done examining the colonization of Staphylococcus aereus (the main causative agent of pyomyositis) in patients with AIDS in the United States presented data supporting the hypothesis that AIDS patients, as well as other immunodefficient patients, are more susceptible to S. aureus and, in turn, pyomyositis.

It is suggested that defective polymorphonuclear neutrophil function, neutropenia, and defective T-lymphocyte function may be what causes that higher incidence rate in immunodeficient patients. Patients with AIDS have less effective monocytes and granulocytes in the phagocytosis of S. aureus than those of healthy individuals, and B lymphocyte function in AIDS patients is defective which could cause a decreased resistance to staphylococcal infections.[9]

Ganesh et al. revealed that the susceptibility of Staphylococcus aureus increased by 49% in patients with asymptomatic HIV.[10] In a study of 8 patients with Staphylococcus aureus pyomyositis, the colonization rate of S. aureus in HIV patients was 37.5% and the colonization rate of S. aureus in AIDS patients was even higher at 58.8%.[11]

It is remarked that persons infected with HIV have a higher prevalence of nasopharyngeal colonization with S. aureus at 44% rather than non-HIV patients at 30.8%.[12] These statistics further confirm the hypothesis that there is an increased susceptibility of HIV and AIDS patients for infections by S. aureus and therefore pyomyosits and other infectious myositis.

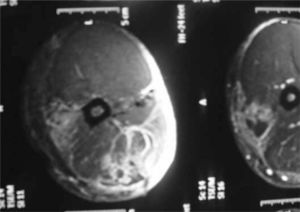

Since pyomyositis occurs in single muscle groups, it is no surprise that cases of pyomyositis have been identified in bodybuilders who use anabolic steroids, known to increase athletic performance. Anabolic steroids are commonly injected into sites in which the athlete desires mass gain, [13] which poses more risks than just the detrimental effects anabolic steroids have on healthy individuals who do not need them for health reasons. In a case study, one bodybuilder began to have pain in his right arm and was diagnosed with pyomyositis of brachial biceps. The diagnosis was a result of culturing of a sample of the patient’s steroid needle, which was positive for S. aereus, which can be treated with antibiotics. [14] Another bodybuilding, anabolic steroid-user with the same diagnosis of S. aereus pyomyositis in the brachial biceps underwent surgical cleaning and a Penrose drain (essentially a tube that drains fluid after surgery) was used in addition to antibiotic treatment. [15] In a third similar case, a steroid user was found to have pyomyositis of the brachial biceps and ipsilateral triceps with culturing revealing presence of S. viridians, which was treated with antibiotics. Figure 2 shows magnetic resonance imaging of the bicep.

In all three cases, the athletes were able to return to full athletic activity within 42 days. Since anabolic steroids in bodybuilders, among other drugs administered without clinical approval, are injected in a nonsterile site, the site at which the steroids are injected is at high risk for infections i.e. pyomyosits.

Psoas Abscess

A psoas abscess is essentially pyomyositis that occurs specifically in the psoas muscle in the lower back and is caused by many different bacteria, but most commonly Mycobacterium tuberculosis and S. aereus. It is classified separately because pyomyositis in the psoas muscle is more common than any other muscle group. Primary psoas abscesses occur directly in the psaos muscle, but secondary infections can occur from nearby bacterial infection that spreads into the psoas muscle. [16] The psoas muscle is subject to infection as a result of its positioning in the body. Because it is very close to the spine, which is subject to infection, bacteria can easily move through the blood and into the psoas muscle. In addition, the muscle is close to other structures like the colon, appendix, jejunum, and pancreas, which can all spread bacteria through blood to the psoas. [17] Psoas abscesses are usually treated with anti-staphylococcal antibiotics because S. aereus is the most common cause, but other antibiotics suited for gram-negative and anaerobic bacteria are necessary in other situations when the infection is polymicrobial. [18]

Primary psoas abscesses are typically caused by S. aereus as seen in cases of pyomyositis, since it is localized in one muscle group. [19]In the same way as other types of pyomyositis, primary psoas abscesses are commonly seen in heroin or other injectable drug users, and immunocompromised individuals are more susceptible. [20] To the right is a CT scan of a psoas abscess by Group A streptococci in a patient with HIV (Figure 3).

In rare cases, primary psoas abscesses can be due to S. pneumoniae, S. milleri, and other streptococci as well as gram-negative bacteria including Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas, Haemophilus, and Pasteurella. [21]

Secondary psoas abscesses are more versatile as they result from bacterial spread from other nearby organs and muscles. S. aereus as well as Mycobacterium tuberculosis, a gram-positive Actinobacteria pathogen that typically causes tuberculosis [22] are the most common causes and are easily spread through vertebrae and other nearby structures into the psoas muscle. S. aereus and Mycobacterium tuberculosis often infect the psoas muscle in patients who have vertebral osteomyelitis, which is a bacterial infection of the spine. [23] In addition, Pott’s disease, which is a Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection of the spine tends to cause a secondary psoas abscess. Secondary psoas abscesses in many cases, though, have more than one microbe involved. Gram-negative E.coli, Enterobacter, Salmonella, and Klebsiella and anaerobes like Clostridium and Bacteroides can all be responsible for secondary psoas abscesses. [24] Because of this, many different antiobiotics may be needed for treatment. Individuals with cancers, appendicitis, and other gastrointestinal infections are more susceptible to secondary psoas abscesses as bacteria can be spread into the psoas from their preexisting conditions. [25]

In an interesting case, a 45-year-old female was diagnosed with a psoas abscess in the right psoas muscle that was first identified through sharp pain in the lower back and thigh. She was not a drug user, but had a job that involved labor and heavy lifting. After an MRI that was negative for vertebral osteomyelitis, a CT scan of the lumbar spine was performed identifying a psoas abscess and can be seen to the left in Figure 4.

Upon culturing, gram-positive cocci were found and were further identified as methicillin-sensitive S. aereus allowing antiobiotic treatment with methicillin to subdue the infection. [26]

Bacterial Myositis

Bacterial Myositis is different from pyomyositis and psoas abscesses because it is unlocalized and usually does not present a large abscess. It is much less common than pyomyositis and psoas abscesses. Bacterial Myositis is usually caused by Streptococcus, although other gram-positive bacteria can lead to myositis including Clostridium species, the bacteria that causes gas gangrene. [27] Clostridium myositis (gas gangrene) caused by C. perfringens is an infection where necrosis is present and usually results from wounds contaminated with soil, since Clostridium species live in soil, and can also be due to surgeries and intravenous drug use. Rare cases of gas gangrene can result with no skin breakage, but typically are due to gastrointestinal problems. [28] When in low-oxygen environments, like inside muscle, Clostridium convert from their spore shape to their vegetative structure and produce toxins that can cause tissue damage. Although gas is found in tissue and is excreted from the wound of most patients with gas gangrene (giving it its name), not all patients will experience gas bubbles, making those cases difficult to diagnose. Commonly, C. perfringens-infected muscle will be unable to contract and there will be less blood from the wound than in uninfected tissue, yielding physical signs of gas gangrene, and when doing culture diagnostics, the absence of neutrophils and presence of gram-positive bacilli indicate the possibility of gas gangrene. In treatment of cases of contaminated wounds, antibiotics that can kill gram-negative organisms as well as gram-positive organisms like C. perfringens must be used because of other organisms potentially contributing to the infection. [29]

Another category of bacterial myositis involves Group A streptococci, which, seen above, can also cause pyomyositis. [30] Group A streptococcal delocalized myositis, caused by Streptococcus pyogenes, is unprompted with no certain condition leading to the infection. Literature claims that pharyngitis and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications may put an individual at risk for Group A streptococci myositis, but the majority of infections seem to have no preliminary factor. The infection typically begins with symptoms associated with the flu and muscle pain follows that is not localized to one muscle group, unlike in pyomyositis. Group A streptococci necrotizing myositis is the most severe form and can be fatal, but is very uncommon. [31] Group A streptococcal necrotizing myositis is worse than other types of myositis because it forms in days, rather than other types of myositis, which can take weeks to become problematic, and the muscle tissue actually dies in this scenario. Necrotizing myositis can be identified by the discovery of muscle necrosis that has gram-positive cocci among the muscle fibers. Because of the necrotizing nature, repeated surgeries are necessary to completely rid the muscle of any necrotizing bacteria and in rare cases, amputation may be necessary. [32] In addition to typical antibiotic treatment after surgery, Clindamycin is used as it stops the formation of toxins released by streptococcal bacteria. [33]

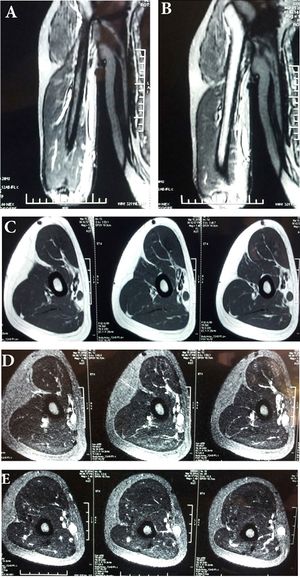

A third, less common category of bacterial myositis is caused by Group B streptococci, Streptococcus agalactiae. Unlike in Group A streptococcal myositis, Group B streptococcal myositis is commonly seen in individuals with diabetes, alcoholism, and other immunocompromising conditions. [34] Group B streptococcal myositis was identified in a male who had a fever and enlargement of both the left and right rectus muscles after straining his groin and abdomen while bowling. Originally, this patient was diagnosed with pyomyositis, but since the infection became delocalized to two different muscle groups, the diagnosis called for further examination. Upon a blood culture, Streptococcus agalactiae was identified, confirming Group B streptococcal myositis, and in Figure 5, an MRI of the rectus muscle can be seen.

[35] Since the patient was a type II diabetic, he was more prone to infection.

Myositis by Fungi

Myositis caused by Fungi is even more rare than other cases of myositis seen above. Fungal myositis has very similar symptoms to bacterial myositis, so culturing is imperative to distinguishing and treating these fungal infections. [36] Fungal myositis is usually the result of prescription steroid use, which prevent the immune system from fighting infection, or chemotherapy, which can cause granulocytopenia, which is where granulcytes (white blood cells) are in too low of quantities to fight infection. [37] Another gateway for fungal myositis is when antibiotics are used for extensive periods of time and kill certain bacteria, allowing fungi to proliferate. HIV patients are the victims of most fungal myositis. [38] Candida species are the most commonly seen fungi responsible, and as seen in bacterial myositis, fungal myositis is not localized in one muscle and typically forms small abscesses. C. tropicalis is the specific species that causes most fungal myositis and can be identified when budding organisms with hyphae are seen in the muscle. [39] Because this is a fungal infection, besides the use of drainage, antifungal agent administration is imperitive, but because it is such a rare infection, it is difficult to diagnose. Other fungi that can cause myositis include Histoplasma capsulatum, Coccidioides, Aspergillus, Pneumocystis jiroveci,and Fusarium. [40]

In a specific case of fungal myositis, a 9-year old Korean boy whom was suffering from leukemia was diagnosed with fungal myositis in 1997.[41] Ten days into chemotherapy treatment, the boy experienced a fever and pain in the left thigh. In addition, his total white blood cell count was 400/ microliter, which is extremely low leading the doctor to look for potential myositis. An excisional biopsy was performed, revealing inflamed necrotic muscle tissue with irregular shaped organisms with hyphae. To the right is a Bright-field microscopy photograph of the fungus (Figure 6).

Cultural diagnostics were negative, but the shape of the organisms allowed them to diagnose fungal myositis. The muscle was surgically drained and the boy was given amphotericin-B, a very strong antifungal agent, since the culturing revealed no specific fungal species. [42] This particular case emphasized the difficulty with diagnosing and treating infectious myositis because the micrograph presents fungi that could not be identified and therefore a treatment must be extreme to account for all fungi. The fungi in the micrograph are not ambiguous, so it is concerning that an unknown microbe could cause such an infection.

Myositis by Viral infection

Influenzas A and B, Enteroviruses, HIV, HTLV-1, and Hepatitis B and C are the most common myositis causing viruses. Because Influenzas are common and reoccurring, myositis has been reported much more than in the other viruses. Influenzas A and B typically cause myositis in the calf muscles, but Influenza B leads to myositis much more often than does Influenza A. Myositis from Influenzas A and B are found most often in children since the immature muscle is thought to be specifically targeted by viruses. Myositis from these influenzas are mild and do not need specific treatment other than the standard treatment for the flu with antiviral medication. [43]

Parasitic Myositis

Many parasites can contribute to myositis and there is not one genus that dominates these infections. Most parasites will form cysts in the muscle, so this myositis is specifically characterized as cysticercosis. Taenia solium, a tapeworm parasite can cause myositis. It is found in pork, and when pork is undercooked and consumed, an individual becomes at risk for myositis, but sometimes T. solium is spread from feces of an individual that already has been infected by it, which is much harder to prevent. Gastric juices activate the eggs that develop into larvae that are able to pass through the intestinal wall and into muscle associated with the central nervous system, but symptoms are rare with little to no muscle inflammation.[44] In an actual report of parasitic myositis by T. solium, a middle aged man who worked a manual labor job began to experience pain and swelling in his bicep, but initially ignored the pain. The pain began to increase and spread into his elbow, and it was discovered that he had cysts developing in the biceps brachii with T. solium present in an antibody test, so was administered ELISA to kill the parasite. [45] An MRI of the bicep was taken to reveal the myositis and can be seen to the right in Figure 7.

To be sure there was no other cyst formation, the brain and eyes were checked in a CT scan, confirming no further spread [46] Other parasites such as Trichinella, a parasitic worm of the nematoda phylym found in undercooked meats, and Toxoplasma gondii, of the Apicomplexa phyla, can also infect musculature. [47] Cooking meat fully is the best prevention technique to rid meat of these parasites.

Conclusion

Overall, myositis is a very uncommon infection, but can be a serious problem. Because it is rare, it is difficult to diagnose and is not the first diagnosis made in most cases. Myositis is ignored by many individuals who may have the infection because of the assumption that it may just be a muscle tear and therefore, the infection worsens before treatment is administered. Although bacteria are the most common cause of myositis, the other groups are prevalent and make treatment extensive since there is not one single treatment that will work for all cases. Even within the bacterial cases themselves, different antibiotics must be administered upon cultural diagnostics to selectively remove infection. In polymicrobial infections, the treatment becomes even more difficult as different microorganisms have such diverse structures that need specific treatment. Myositis is not an infection that can be completely diminished with one cure, so it will continue to appear in individuals, especially in those in immunocompromised condition. Although it is rare, it must not be overlooked in the medical field and is a fascinating infection as it can be due to organisms spread across all domains of life.

References

- ↑ [Crum-Cianflone, Nancy F. “Bacterial, Fungal, Parasitic, and Viral Myositis.” Clinical Microbiology Reviews 21.3 (2008): 473–494. PMC]

- ↑ [Crum-Cianflone, Nancy F. “Bacterial, Fungal, Parasitic, and Viral Myositis.” Clinical MicrobiologyReviews 21.3 (2008): 473–494. PMC]

- ↑ [Crum-Cianflone, Nancy F. “Bacterial, Fungal, Parasitic, and Viral Myositis.” Clinical Microbiology Reviews 21.3 (2008): 473–494. PMC]

- ↑ [Horn, C. V., and S. Master. 1968. Pyomyositis tropicans in Uganda. East Afr. Med. ]

- ↑ [Levin, M. J., and P. Gardner. 1971. “Tropical” pyomyositis: an unusual infection due to Staphylococcus aureus. N. Engl. J. Med. 284:196-198.]

- ↑ [Crum-Cianflone, Nancy F. “Bacterial, Fungal, Parasitic, and Viral Myositis.” Clinical Microbiology Reviews 21.3 (2008): 473–494. PMC]

- ↑ [Widrow, C. A., S. M. Kellie, B. R. Saltzman, and U. Mathur-Wagh. 1991. Pyomyositis in patients with the human immunodeficiency virus: an unusual form of disseminated bacterial infection. Am. J. Med]

- ↑ [Christin, L., and G. A. Sarosi. 1992. Pyomyositis in North America: case reports and review. Clin. Infect. Dis. 15:668-677]

- ↑ [Antony, S.J., and Kernodle, D.S. Nontropical Pyomyosits in patients with AIDS. J Natl Med Assoc, 1996.]

- ↑ [Ganesh R, Castle D, McGibbon D, Phillips I, Bradbeer C: Staphylococcal carriage and HIV infection. Lancet 1989, ii: 558.]

- ↑ [Weinkel, T., Schiller, R., Fehrenbach, E.J., Pohle H.D. Association between Staphylococcus aureus Nasopharyngeal Colonization and Septicemia in Patients Infected with the Human Immunodeficiency Virus. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis., November 1992.]

- ↑ [Antony, S.J., and Kernodle, D.S. Nontropical Pyomyosits in patients with AIDS. J Natl Med Assoc, 1996.]

- ↑ [Filho, Nivaldo Souza Cardozo et al. “PYOMYOSITIS IN ATHLETES AFTER THE USE OF ANABOLIC STEROIDS - CASE REPORTS.” Revista Brasileira de Ortopedia 46.1 (2011): 97–100. PMC]

- ↑ [Filho, Nivaldo Souza Cardozo et al. “PYOMYOSITIS IN ATHLETES AFTER THE USE OF ANABOLIC STEROIDS - CASE REPORTS.” Revista Brasileira de Ortopedia 46.1 (2011): 97–100. PMC]

- ↑ [Filho, Nivaldo Souza Cardozo et al. “PYOMYOSITIS IN ATHLETES AFTER THE USE OF ANABOLIC STEROIDS - CASE REPORTS.” Revista Brasileira de Ortopedia 46.1 (2011): 97–100. PMC]

- ↑ [ Crum-Cianflone, Nancy F. “Bacterial, Fungal, Parasitic, and Viral Myositis.” Clinical Microbiology Reviews 21.3 (2008): 473–494. PMC]

- ↑ [ Crum-Cianflone, Nancy F. “Bacterial, Fungal, Parasitic, and Viral Myositis.” Clinical Microbiology Reviews 21.3 (2008): 473–494. PMC]

- ↑ [Tomich, Eric B., and David Della-Giustina. “Bilateral Psoas Abscess in the Emergency Department.” Western Journal of Emergency Medicine 10.4 (2009)]

- ↑ [Gruenwald, I., J. Abrahamson, and O. Cohen. 1992. Psoas abscess: case report and review of the literature. J. Urol]

- ↑ [Santaella, R. O., E. K. Fishman, and P. A. Lipsett. 1995. Primary vs secondary iliopsoas abscess. Presentation, microbiology, and treatment. Arch. Surg]

- ↑ [Crum-Cianflone, Nancy F. “Bacterial, Fungal, Parasitic, and Viral Myositis.” Clinical Microbiology Reviews 21.3 (2008): 473–494. PMC]

- ↑ [MicrobeWiki, Mycobacterium tuberculosis]

- ↑ [Crum-Cianflone, Nancy F. “Bacterial, Fungal, Parasitic, and Viral Myositis.” Clinical Microbiology Reviews 21.3 (2008): 473–494. PMC]

- ↑ [Santaella, R. O., E. K. Fishman, and P. A. Lipsett. 1995. Primary vs secondary iliopsoas abscess. Presentation, microbiology, and treatment]

- ↑ [van den Berge, M., T. de Marie, S. Kuipers, A. R. Jansz, and B. Bravenboer. 2005. Psoas abscess: report of a series and review of the literature. Neth. J. Med]

- ↑ [Tomich, Eric B., and David Della-Giustina. “Bilateral Psoas Abscess in the Emergency Department.” Western Journal of Emergency Medicine 10.4 (2009)]

- ↑ [Adams, E. M., S. Gudmundsson, D. E. Yocum, R. C. Haselby, W. A. Craig, and W. R Sundstrom. 1985. Streptococcal myositis. Arch. Intern. Med.]

- ↑ [ El-Masry, S. 2005. Spontaneous gas gangrene associated with occult carcinoma of the colon: a case report and review of the literature. Int. Surg]

- ↑ [Crum-Cianflone, Nancy F. “Bacterial, Fungal, Parasitic, and Viral Myositis.” Clinical Microbiology Reviews 21.3 (2008): 473–494. PMC]

- ↑ [Kallen, P. S., J. S. Louie, K. M. Nies, and A. S. Bayer. 1982. Infectious myositis and related syndromes. Semin. Arthritis Rheum]

- ↑ [Subramanian, K. N., and K. S. Lam. 2003. Malignant necrotizing streptococcal myositis: a rare and fatal condition. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br]

- ↑ [Crum-Cianflone, Nancy F. “Bacterial, Fungal, Parasitic, and Viral Myositis.” Clinical Microbiology Reviews 21.3 (2008): 473–494. PMC]

- ↑ [Stevens, D. L., A. E. Gibbons, R. Bergstrom, and V. Winn. 1988. The Eagle effect revisited: efficacy of clindamycin, erythromycin, and penicillin in the treatment of streptococcal myositis. J. Infect. Dis]

- ↑ [Crum-Cianflone, Nancy F. “Bacterial, Fungal, Parasitic, and Viral Myositis.” Clinical Microbiology Reviews 21.3 (2008): 473–494. PMC]

- ↑ [Back, S. A., T. O'Neill, G. Fishbein, and G. Gwinup. 1990. A case of group B streptococcal pyomyositis]

- ↑ [Crum-Cianflone, Nancy F. “Bacterial, Fungal, Parasitic, and Viral Myositis.” Clinical Microbiology Reviews 21.3 (2008): 473–494. PMC]

- ↑ [Tsai, S. H., Y. J. Peng, and N. C. Wang. 2006. Pyomyositis with hepatic and perinephric abscesses caused by Candida albicans in a diabetic nephropathy patient. ]

- ↑ [Crum-Cianflone, Nancy F. “Bacterial, Fungal, Parasitic, and Viral Myositis.” Clinical Microbiology Reviews 21.3 (2008): 473–494. PMC]

- ↑ [Crum-Cianflone, Nancy F. “Bacterial, Fungal, Parasitic, and Viral Myositis.” Clinical Microbiology Reviews 21.3 (2008): 473–494. PMC]

- ↑ [ Crum-Cianflone, Nancy F. “Bacterial, Fungal, Parasitic, and Viral Myositis.” Clinical Microbiology Reviews 21.3 (2008): 473–494. PMC]

- ↑ [Kang, Chin Moo, et al., Localized Muscular Mucormycosis in a Child with Acute Leukemia, 1997]

- ↑ [Kang, Chin Moo, et al., Localized Muscular Mucormycosis in a Child with Acute Leukemia, 1997]

- ↑ [Crum-Cianflone, Nancy F. “Bacterial, Fungal, Parasitic, and Viral Myositis.” Clinical Microbiology Reviews 21.3 (2008): 473–494. PMC]

- ↑ [Crum-Cianflone, Nancy F. “Bacterial, Fungal, Parasitic, and Viral Myositis.” Clinical Microbiology Reviews 21.3 (2008): 473–494. PMC]

- ↑ [Chaudhari, Prasad et al. A rare case of isolated cysticercosis of the biceps brachii muscle.]

- ↑ [Chaudhari, Prasad et al. A rare case of isolated cysticercosis of the biceps brachii muscle]

- ↑ [Crum-Cianflone, Nancy F. “Bacterial, Fungal, Parasitic, and Viral Myositis.” Clinical Microbiology Reviews 21.3 (2008): 473–494. PMC]

Authored for BIOL 238 Microbiology, taught by Joan Slonczewski, 2017, Kenyon College.