The role of Bifidobacterium longum in a healthy human gut community: Difference between revisions

| Line 32: | Line 32: | ||

With their interesting “Y” shape, <i>Bifidobacterium longum</i> are considered to be bacilli, rod-shaped, organisms. The use of their unique “Y” is unknown, although it does increase their surface area to volume ratio and could also assist in compartmentalizing cellular structures. <i>B. longum</i> are naturally found in the human digestive system and the vagina [[#References|[7]]]. Both of these habitats are hypoxic, which makes sense because <i>B. longum</i> are anaerobic microorganisms. <i>B. longum</i> also lack the catalase enzyme, an enzyme commonly found in aerobic organisms, furthering its anaerobic evidence [[#References|[7]]]. <i>B. longum</i> stain gram-positive meaning they have a single cell membrane and a thick peptidoglycan cell wall. The size of <i>B. longum</i> ranges from 4-8µm. | With their interesting “Y” shape, <i>Bifidobacterium longum</i> are considered to be bacilli, rod-shaped, organisms. The use of their unique “Y” is unknown, although it does increase their surface area to volume ratio and could also assist in compartmentalizing cellular structures. <i>B. longum</i> are naturally found in the human digestive system and the vagina [[#References|[7]]]. Both of these habitats are hypoxic, which makes sense because <i>B. longum</i> are anaerobic microorganisms. <i>B. longum</i> also lack the catalase enzyme, an enzyme commonly found in aerobic organisms, furthering its anaerobic evidence [[#References|[7]]]. <i>B. longum</i> stain gram-positive meaning they have a single cell membrane and a thick peptidoglycan cell wall. The size of <i>B. longum</i> ranges from 4-8µm. | ||

<i>Bifidobacterium longum</i> is more common in the gastrointestinal tract of infants as opposed to adults. Nine out of every 10 bacteria in an infant’s stool sample is <i>B. longum</i>, while only 3% of adult’s gut microbiota is <i>B. longum</i> [[#References|[8]]]. This can be explained by the special metabolization <i>B. longum</i> possesses for oligosaccharides. <i>B. longum</i> have a large quantity of genes responsible for transcribing proteins that catabolize a variety of oligosaccharides [[#References|[7]]]. Infants only food source is their mother’s breast milk. There are many oligosaccharides that are unique to and highly concentrated in breast milk [[#References|[9]]]. | <i>Bifidobacterium longum</i> is more common in the gastrointestinal tract of infants as opposed to adults. Nine out of every 10 bacteria in an infant’s stool sample is <i>B. longum</i>, while only 3% of adult’s gut microbiota is <i>B. longum</i> [[#References|[8]]]. This can be explained by the special metabolization <i>B. longum</i> possesses for oligosaccharides. <i>B. longum</i> have a large quantity of genes responsible for transcribing proteins that catabolize a variety of oligosaccharides [[#References|[7]]]. Infants only food source is their mother’s breast milk. There are many oligosaccharides that are unique to and highly concentrated in breast milk [[#References|[9]]]. It is logical that <i>B. longum</i> assists infants in harvesting as many nutrients as possible from their lone food source in order to grow and develop normally. Oligosaccharides are short carbohydrate polymers containing 3-10 simple sugars linked through oxygen or nitrogen linkages. Sources of oligosaccharides include breast milk and plant fibers [[#References|[10]]]. Since <i>B. longum</i> is located in the vagina, infants are able to acquire this microorganism by passing through the birth canal. As humans mature and their diets diversify, they require a greater variety of microorganisms to assist in digestion. However, in vitro experiments have shown that <i>B. longum</i> can assist IECs to ultimately prevent having a leaky gut [[#References|[11]]]. In vivo experiments have also been done with <i>B. longum</i> to show its beneficial effect on the gastrointestinal system [[#References|[12]]]. | ||

==Section 4== | ==Section 4== | ||

Revision as of 02:58, 28 April 2016

Classification

Kingdom: Bacteria

Division: Actinobacteria

Class: Actinobacteria

Order: Bifidobacteriales

Family: Bifidobacteriaceae

Genus: Bifidobacterium

Species: longum

By Luke Calcei

An Overview of Digestive Health

A healthy human gut is imperative to living a healthy life. Faulty digestion can limit the amount of nutrients extracted from healthy food sources. Unhealthy immune systems lend themselves to having a ‘leaky gut’ [1]. Leaky guts are caused by weak intestinal epithelial cells (IECs). Although the intestines are deep within humans, the intestinal barrier is a primary barrier from the external environment. Although, it is not typically viewed this way, a leaky gut is similar to having an open wound. Intestinal wounds occur when pathogenic microflora out compete healthy gut microflora. When flourishing, pathogenic microflora release toxins and inflammatory factors, which compromises IECs [1]. Compromised IECs allow those toxins and undigested food particles into the bloodstream, activating the immune system. If this is a continuous problem, the immune system can become overactive causing various autoimmune diseases where the immune system attacks its own cells. Autoimmune diseases include lupus, alopecia, and arthritis and affect approximately 50 million Americans, nearly 20% of the population [2]. Autoimmune diseases are not life threatening, yet they dramatically inconvenience life and distract the immune system, thus making those with autoimmune diseases more susceptible to contracting and being effected by minor illnesses. Autoimmune responses can be triggered by environmental toxins, foreign bacteria, and viruses in individuals who are genetically predisposed [2]. Improving digestive health can decrease autoimmune incidences improving the overall health of populations in developed countries.

Digestive health can be influenced by the foods you eat, which is directly linked to the microorganisms inhabiting the human gut. Bifidobacterium is a genera of bacterium that has been linked to improving digestive health.

The Discovery and History of Bifidobacterium longum

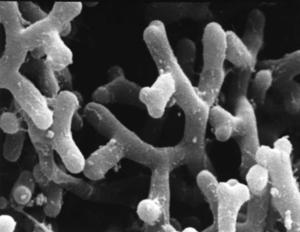

The Pasteur Institute has played a large role in the discovery and knowledge of Bifidobacterium. Bifidobacterium were first discover in 1899 by a French pediatrician, Henry Tissier, who observed a peculiar “Y” shaped microorganism in the stool of infants having diarrhea [3]. Tissier named these microorganisms using the Latin root “bifid” meaning divided by a deep cleft, like the letter “Y” (Figure 1)[4]. Later, in 1907, Nobel prize winning immunologist, Elie Metchnikoff, suggested implanting beneficial bacteria orally would help the digestive system. Tissier and Metchnikoff were the first to introduce the idea of probiotics, ingesting healthy gut microbes to improve overall digestive health.

In 2002, three previously separate species of Bifidobacterium merged into one species due to DNA similarities [5]. B. longum, B. infantis, and B. suis became B. longum as the three shared 97% DNA similarities [6]. B. longum subspecies infantis strain 35624 has become the main microorganism related to beneficiary gut function in humans.

An Overview of Bifidobacterium longum

With their interesting “Y” shape, Bifidobacterium longum are considered to be bacilli, rod-shaped, organisms. The use of their unique “Y” is unknown, although it does increase their surface area to volume ratio and could also assist in compartmentalizing cellular structures. B. longum are naturally found in the human digestive system and the vagina [7]. Both of these habitats are hypoxic, which makes sense because B. longum are anaerobic microorganisms. B. longum also lack the catalase enzyme, an enzyme commonly found in aerobic organisms, furthering its anaerobic evidence [7]. B. longum stain gram-positive meaning they have a single cell membrane and a thick peptidoglycan cell wall. The size of B. longum ranges from 4-8µm.

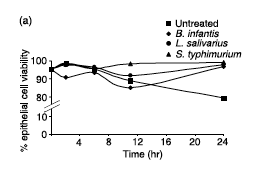

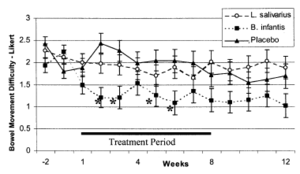

Bifidobacterium longum is more common in the gastrointestinal tract of infants as opposed to adults. Nine out of every 10 bacteria in an infant’s stool sample is B. longum, while only 3% of adult’s gut microbiota is B. longum [8]. This can be explained by the special metabolization B. longum possesses for oligosaccharides. B. longum have a large quantity of genes responsible for transcribing proteins that catabolize a variety of oligosaccharides [7]. Infants only food source is their mother’s breast milk. There are many oligosaccharides that are unique to and highly concentrated in breast milk [9]. It is logical that B. longum assists infants in harvesting as many nutrients as possible from their lone food source in order to grow and develop normally. Oligosaccharides are short carbohydrate polymers containing 3-10 simple sugars linked through oxygen or nitrogen linkages. Sources of oligosaccharides include breast milk and plant fibers [10]. Since B. longum is located in the vagina, infants are able to acquire this microorganism by passing through the birth canal. As humans mature and their diets diversify, they require a greater variety of microorganisms to assist in digestion. However, in vitro experiments have shown that B. longum can assist IECs to ultimately prevent having a leaky gut [11]. In vivo experiments have also been done with B. longum to show its beneficial effect on the gastrointestinal system [12].

Section 4

Conclusion

References

1. Kathy, M. "The Surprising Link between Alopecia and the Gut." OptiBac Probiotics. Wren Laboratories, 9 Oct. 2015. Web. 11 Apr. 2016. <http://www.optibacprobiotics.co.uk/blog/2015/10/the-surprising-link-between-alopecia-and-the-gut>.

2. American Autoimmune Related Diseases Association. "Questions and Answers." AARDA. AARDA, 12 Dec. 2015. Web. 18 Apr. 2016. <http://www.aarda.org/autoimmune-information/questions-and-answers/>.

3. Oyetayo, V.O. and Oyetayo, F. L. 2004. Potential of probiotics as biotherapeutic agents targeting the innate immune system. African Journal of Biotechnology 4:123-127. https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=0ahUKEwjyr5GanbDMAhUlroMKHQbAChkQFggfMAA&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.academicjournals.org%2Farticle%2Farticle1379957698_Oyetayo%2520and%2520Oyetayo.pdf&usg=AFQjCNGyDMebAZivghDU34h_isLC_XmQLA&bvm=bv.120853415,d.amc

4. "bifid". Dictionary.com Unabridged. Random House, Inc. 20 Apr. 2016. <Dictionary.com http://www.dictionary.com/browse/bifid>.

5. Sakata, S., Kitahara, M., Sakamoto, M., Hayashi, H., Fukuyama, M. & Benno, Y. 2002. Unification of Bifidobacterium infantis and Bifidobacterium suis as Bifidobacterium longum. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 52: 1945–1951. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12508852

6. Mattarelli, P., C. Bonaparte, B. Pot, B. Biavati. 2008. Proposal to reclassify the three biotypes of Bifidobacterium longum as three subspecies. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 58: 767-772. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18398167

7. Schell, M. A., M. Karmirantzou, B. Snell, D. Vilanova, B. Berger, G. Pessi, M. C. Zwahlen, F. Desiere, P. Bork, M. Delley, R. D. Pridmore, F. Arigoni. 2002. The genome sequence of Bifidobacterium longum reflects its adaptation to the human gastrointestinal tract. PNAS 99: 14422-14427. http://www.pnas.org/content/99/22/14422.full

8. Garrido, D., S.R. Moyano, R. J. Espinoza, H.J. Eom, D.E. Block, D.A. Mills. 2013. Utilization of galatoogligosaccharides by Bididobacterium longum subsp. infantis isolates. Food Microbiol 33(2): 262-270. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3593662/

9. Bode, L. 2012. Human milk oligosaccharides: every baby needs a sugar mama. Glycobiology 22: 1147-1162. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22513036

10. National Library of Medicine. "Oligosaccharides." U.S National Library of Medicine. U.S. National Library of Medicine, 2011. Web. 25 Apr. 2016. <https://www.nlm.nih.gov/cgi/mesh/2011/MB_cgi?mode=&term=Oligosaccharides>.

11. O'Hara, A., O'Regan, P., Fanning, A., O'Mahony, C., MacSharry, J., Lyons, A., Bienenstock, J., O'Mahony, L., Shanahan, F. "Functional modulation of human intestinal epithelial cell responses by Bifidobacterium infantis and Lactobacillus salivarius." 2006. Immunology 118:202-215.http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1365-2567.2006.02358.x/full

12. O’Mahony, L., J. McCarthy, P. Kelly, G. Hurley, F. Luo, K. Chen, G. C. O’Sullivan, B. Kiely, J. K. Collins, F. Shanahan, E. M. M. Quigley. 2005. Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium in irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 128: 541-551. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0016508504021559

13. Taylor, Paul. "C-section Babies Missing Crucial Gut Bacteria." The Globe and Mail. Health Navigator, 11 Feb. 2013. Web. 25 Apr. 2016. <http://www.theglobeandmail.com/life/health-and-fitness/health-navigator/c-section-babies-missing-crucial-gut-bacteria-study-finds/article8440728/>.

14. Group, Edward. "Probiotic Foods." Global Healing Center. N.p., 21 Jan. 2011. Web. 25 Apr. 2016. <http://www.globalhealingcenter.com/natural-health/probiotic-foods/>.

15. Watson, Elaine. "US per Capita Spending on Probiotic Supplements Expected to Nearly Double by 2016." Nutra. William Reed Business Media, 2 Feb. 2012. Web. 18 Apr. 2016. <http://www.nutraingredients-usa.com/Markets/US-per-capita-spending-on-probiotic-supplements-expected-to-nearly-double-by-2016>.

16. Jones, Linda B. "Anaerobic Bacteria Culture." Anaerobic Bacteria Culture. National Institues of Health, 5 Apr. 2003. Web. 15 Apr. 2016. <http://www.surgeryencyclopedia.com/A-Ce/Anaerobic-Bacteria-Culture.html>.

17. Hedges, Jones C., Cherie A. Singer, and William T. Gerthoffer. 2000. Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases Regulate Cytokine Gene Expression in Human Airway Myocytes. American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology, 23: 86-94.http://www.atsjournals.org/doi/abs/10.1165/ajrcmb.23.1.4014#.Vx7MvD-R_R1

18. Eskdale, J., D. Kube, H. Tesch, G. Gallagher. 1997. Mapping the human IL10 gene and further characterization of the 5’ flanking sequence. Immunogenetics 46: 120-128. http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs002510050250

19. Murphy, K. M., A. O’Garra, S. F. Wolf, C. S. Tripp, S. E. Macatonia, C. S. Hsieh. 1993. Development of TH1 CD4+ T cells through IL-12 produced by Listeria-induced macrophages. Science 260: 547-549. http://science.sciencemag.org/content/260/5107/547.long

20. International Foundation for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. "Facts About IBS." About IBS. Nternational Foundation for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders, 21 Apr. 2016. Web. 20 Apr. 2016. <https://www.aboutibs.org/site/what-is-ibs/facts/>.

21. Holzer, P., A. Farzi. 2014. Neuropeptides and the Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis. Adv Exp Med Biol 817: 195-219. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4359909/

22. Sample, Ian. "Probiotic Bacteria May Aid against Anxiety and Memory Problems." The Guardian. Guardian News and Media, 18 Oct. 2015. Web. 19 Apr. 2016. <https://www.theguardian.com/science/2015/oct/18/probiotic-bacteria-bifidobacterium-longum-1714-anxiety-memory-study>.

23. Eveleth, Rose. "There Are 37.2 Trillion Cells in Your Body." Smithsonian. Smithsonian Institution, 24 Oct. 2013. Web. 17 Apr. 2016. <http://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/there-are-372-trillion-cells-in-your-body-4941473/?no-ist>.

24. Sparks, and Honey. "Humans: 10% Human and 90% Bacterial." Big Think. N.p., 22 May 2013. Web. 20 Apr. 2016. <http://bigthink.com/amped/humans-10-human-and-90-bacterial>.

25. Gest, H. 2004. The discovery of microorganisms by Robert Hooke and Antoni Van Leeuwenhoek, fellows of the Royal Society. Notes Rec R Soc Land 58: 187-201. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15209075

Authored for BIOL 238 Microbiology, taught by Joan Slonczewski, 2016, Kenyon College.