Mycobacterium tuberculosis

A Microbial Biorealm page on the genus Mycobacterium tuberculosis

Classification

Higher order taxa

Domain: Bacteria; Phylum: Actinobacteria; Class: Actinobacteria; Order: Actinomycetales; family: Mycobacteriaceae; Genus: Mycobacterium

Species

The Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex (MTC) consists of Mycobacterium africanum, Mycobacterium bovis, Mycobacterium canettii, Mycobacterium microti, Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

Description and significance

Mycobacterium tuberculosis is a acid fast bacteria, which can form acid-stable complexes when certain arylmethane dyes are added. (4) All species of mycobacteria have ropelike structures of peptidoglycan that are arranged in such a way to give them properties of an acid fast bacteria. (4) Mycobacteria are abundant in soil and water, but Mycobacterium tuberculosis is mainly identified as a pathogen that lives in the host. Some species in its Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex have adapted their genetic structure specifically to infect human populations.

M. tuberculosis can be isolated in labs and stored at –80 degrees to be studied extensively, and the most commonly used strain of M. tuberculosis is the H37Rv strain. One way to study M. tuberculosis in culture is to collect samples of mononuclear cells in peripheral blood samples from a healthy human donor and challenge macrophages with the MTC. M. tuberculosis has very simple growth requirements and is able to grow slowly in harsh conditions. Their acid-fast property is the strongest when there is glycerol around. However, when glucose is the main source of nutrient, the utilization of glycerol by M. tuberculosis is inhibited. Therefore, it’s been shown that glutatmate, and not glucose, is actually the main source of nutrient for initiating growth. (4)

Since as many as 32% of the human population is affected by Tuberculosis (TB), an airborne disease caused by infection of M. tuberculosis in one way or another, and about 10% of them becomes ill per year (6), it is not hard to imagine the significance in understanding the genome of the pathogen to develop and improve strategies for treatment by developing specific drugs that target the gene products of M. tuberculosis.

Genome structure

Mycobacterium tuberculosis has circular chromosomes of about 4,200,000 nucleotides long. The G+C content is about 65%. (13)

The genome of M. tuberculosis was studied generally using the strain M. tuberculosis H37Rv. The genome contains about 4000 genes. Genes that code for lipid metabolism are a very important part of the bacterial genome, and 8% of the genome is involved in this activity. (7)

The different species of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex show a 95-100% DNA relatedness based on studies of DNA homology, and the sequence of the 16S rRNA gene are exactly the same for all the species. So some scientists suggest that they should be grouped as a single species while others argue that they should be grouped as varieties or subspecies of M. tuberculosis. (2)

Plasmids in M. tuberculosis are important in transferring virulence because genes on the plasmids are more easily transferred than genes located on the chromosome. One such 18kb plasmid in the M. tuberculosis H37Rv strain was proven to conduct gene transfers.

Cell structure and metabolism

M. tuberculosis has a tough cell wall that prevents passage of nutrients into and excreted from the cell, therefore giving it the characteristic of slow growth rate. The cell wall of the pathogen looks like a Gram-positive cell wall. The cell envelope contains a polypeptide layer, a peptidoglycan layer, and free lipids. In addition, there is also a complex structure of fatty acids such as mycolic acids that appear glossy. (8) The M. tuberculosis cell wall contains three classes of mycolic acids: alpha-, keto- and methoxymycolates. The cell wall also contains lipid complexes including acyl glcolipids and other complex such as free lipids and sulfolipids. There are porins in the membrane to facilitate transport. Beneath the cell wall, there are layers of arabinogalactan and peptidoglycan that lie just above the plasma membrane. (14)

The M. tuberculosis genome encodes about 190 transcriptional regulators, including 13 sigma factors, 11 two-component system and more than 140 transcription regulators. Several regulators have been found to respond to environmental distress, such as extreme cold or heat, iron starvation, and oxidative stress. (11) To survive in these harsh conditions for a prolonged period in the host, M. tuberculosis had learned to adapt to the environment by allowing or inhibiting transcription according to its surroundings.(3)

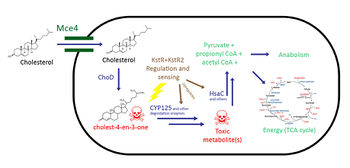

Cholesterol Catabolism

(note: references for this section are included at the bottom of this section)

Cholesterol metabolism has been studied extensively because of its possible therapeutic applications in Tuberculosis(TB) infections. It has been shown numerous times that TB requires cholesterol for virulence in vivo, because Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb), the causative agent, utilizes cholesterol as a source of carbon, energy, and steroid-derived metabolites throughout the course of infection (1-3,13,18). As a result, therapies targeting this catabolic dependency may be developed to treat TB once it’s better understood.

Regulation

The cholesterol catabolic pathway in Mycobacteria is regulated by KstR and KstR2, which regulate gene expression in a similar fashion to Tetracycline resistance regulators (TetR-like proteins) (4, 5). These TetR-like proteins function by binding to the operator and repressing transcription of its regulon, which represses cholesterol catabolism genes, in the absence of cholesterol (4, 5). In the presence of cholestenone – a cholesterol metabolite – KstR and KstR2 are released from the operator to allow transcription of cholesterol catabolism genes; furthermore, they also repress transcription of their own gene, resulting in less overall KstR and KstR2 being made (6).

Of these two proteins, KstR is better understood. KstR regulates a large regulon of proteins involved in lipid and cholesterol catabolism, while KstR2 is known to be involved in regulating a smaller and independent regulon within the KstR regulon that is hypothesized to be involved in the cholesterol catabolism pathway (4, 5). These two proteins also work independently from each other, suggesting perhaps the transcription of these regulons happen during different stages of infection (4).

Uptake

The uptake of cholesterol uses the Mce4 transport system on the M. tuberculosis cell wall, and is regulated by KstR (3,7-9). The exact mechanism of this transporter is not known, but it is known that Mce4 is an ATP-binding cassette transport system consisting of more than 8 proteins (7). Additionally, this transporter is able to transport other steroids that are similar in structure to cholesterol, including 4-androstene-3,17-dione (AD), which is a metabolite of cholesterol catabolism (7).

Catabolic Pathway

First, cholesterol is first oxidized into cholest-4-en-3-one (cholestenone) by a dehydrogenase protein in MTB called ChoD (1,10). This dehydrogenase oxidizes cholesterol into cholestenone, using the reduction of NAD+ to NADH as the oxidizing agent (11). The catabolism of cholesterol is then split into two parts: 1) the alkyl side chain degradation which eventually feeds into the TCA cycle (1) and 2) the ring cleavage of the steroid body (12). There is strong evidence that the alkyl side chain degradation occurs first (10).

The alkyl side chain degradation pathway is similar to normal alkane degradation systems. The pathway involves many oxygenases leading up to three beta-oxidation cycles (8,12). This process yields one molecule of acetyl-CoA and 2 molecules of propanyl-CoA, which can then generate energy via the TCA cycle or be used for anabolism. The enzymes that are involved in this oxidation process are homologous to the enzymes involved in classical fatty acid beta oxidation, however, they have evolved a unique structure in order to accommodate large, bulky steroid substrates (19).

The pathway for the degradation of the steroid rings is much less understood compared to the alkyl side chain. After the alkyl side chain is degraded, the remaining AD molecule is converted into 1,4-androstenedione (ADD) (8). This is followed by many ring-opening steps catalyzed by various oxygenases (15). After the opening of the A and B rings, the alkene that is produced is degraded into propionyl-CoA and pyruvate, which can be used for energy or anabolism. It is not known how the C and D rings are degraded (8).

Role of Cholesterol in Tuberculosis Infections

Tuberculosis infections have unique virulence factors compared to most pathogens. They infect host cell [ http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Macrophage macrophages] and persist inside phagosomes where there are limited nutrients (3). Tuberculosis’ unique ability to utilize cholesterol, which is a common component of human cell membranes, plays a role in its persistence (3). Furthermore, because the cholesterol catabolism pathway requires a large number of oxygenases, it is no surprise that TB infects the lungs where oxygen concentrations are highest (8).

Therapeutic applications

Because TB requires cholesterol to persist during an infection, inhibiting the Mce4 transporter can be a novel therapeutic option. Understanding the mechanism of the Mce4 transport system can provide insight into possible anti-mycobacterial targets.

Targeting the KstR regulation system may also be a possible treatment. If the KstR proteins are prohibited from unbinding its operator and de-repressing its regulon, TB’s cholesterol catabolism genes would not be expressed. As a result, the ability for TB to persist inside macrophages would be lost and thus would be faster to treat.

Within the cholesterol catabolism pathway, there are many metabolites that may be toxic. Cholestenone, the first product of the cholesterol pathway, has shown to be toxic and can kill the cell (13). Cholestenone is used up by CYP125, and knocking out CYP125 causes an accumulation of toxic cholestenone which kills the cell.16 Furthermore, a previous study revealed that knocking out HsaC resulted in catechol formation15, which can harm the cell due to formation of free radicals that can cause irreparable DNA damage (17). Inhibiting CYP125 and HsaC may also be possible therapeutic options in which the cell poisons itself to death (16).

References

1. Brzostek, A., Dziadek, B., Rumijowska-Galewicz, A., Pawelczyk, J. & Dziadek, J. Cholesterol oxidase is required for virulence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 275, 106 (2007).

2. Brzostek, A., Pawelczyk, J., Rumijowska-Galewicz, A., Dziadek, B. & Dziadek, J. Mycobacterium tuberculosis Is Able To Accumulate and Utilize Cholesterol. The Journal of Bacteriology 191, 6584-6591 (2009).

3. Pandey, A. K. & Sassetti, C. M. Mycobacterial Persistence Requires the Utilization of Host Cholesterol. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105, 4376-4380 (2008).

4. Uhía, I., Galán, B., Medrano, F. J. & García, J. L. Characterization of the KstR-dependent promoter of the gene for the first step of the cholesterol degradative pathway in Mycobacterium smegmatis. Microbiology 157, 2670 (2011).

5. Kendall, S. L. et al. A highly conserved transcriptional repressor controls a large regulon involved in lipid degradation in Mycobacterium smegmatis and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol. Microbiol. 65, 684-699 (2007).

6. Ramos, J. L. et al. The TetR family of transcriptional repressors. Microbiology and molecular biology reviews : MMBR 69, 326-356 (2005).

7. William W. Mohn et al. The Actinobacterial mce4 Locus Encodes a Steroid Transporter. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 35368-35374 (2008).

8. Van der Geize, R. et al. A Gene Cluster Encoding Cholesterol Catabolism in a Soil Actinomycete Provides Insight into Mycobacterium tuberculosis Survival in Macrophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104, 1947-1952 (2007).

9. Chang, J. C. et al. igr Genes and Mycobacterium tuberculosis cholesterol metabolism. J. Bacteriol. 191, 5232-5239 (2009).

10. Chiang, Y. R. et al. Cholest-4-en-3-one-delta 1-dehydrogenase, a flavoprotein catalyzing the second step in anoxic cholesterol metabolism. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 107-113 (2008).

11. Yang, X., Dubnau, E., Smith, I. & Sampson, N. S. Rv1106c from Mycobacterium tuberculosis is a 3beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase. Biochemistry (N. Y. ) 46, 9058 (2007).

12. Griffin, J. E. et al. High-resolution phenotypic profiling defines genes essential for mycobacterial growth and cholesterol catabolism. PLoS pathogens 7, e1002251 (2011).

13. Ouellet, H. et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis CYP125A1, a steroid C27 monooxygenase that detoxifies intracellularly generated cholest-4-en-3-one. Mol. Microbiol. 77, 730 (2010).

14. Thomas, S. T., VanderVen, B. C., Sherman, D. R., Russell, D. G. & Sampson, N. S. Pathway profiling in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: elucidation of cholesterol-derived catabolite and enzymes that catalyze its metabolism. The Journal of biological chemistry 286, 43668-43678 (2011).

15. Yam, K. C. et al. Studies of a ring-cleaving dioxygenase illuminate the role of cholesterol metabolism in the pathogenesis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS pathogens 5, e1000344 (2009).

16. Ouellet, H., Johnston, J. B. & de Montellano, P. R. O. Cholesterol catabolism as a therapeutic target in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Trends Microbiol. 19, 530 (2011).

17. Schweigert, N., Zehnder, A. J. & Eggen, R. I. Chemical properties of catechols and their molecular modes of toxic action in cells, from microorganisms to mammals. Environ. Microbiol. 3, 81 (2001).

18. Wipperman, Matthew, F., Sampson, Nicole, S., Thomas, Suzanne, T. Pathogen Roid Rage: Cholesterol utilization by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 49(4):269-93. (2014) doi: 10.3109/10409238.2014.895700.

19. Wipperman, M.F., Yang, M., Thomas, S.T., Sampson, N.S. Shrinking the FadE proteome of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: Insights into cholesterol metabolism through identification of an α2β2 heterotetrameric acyl coenzyme A dehydrogenase family. J Bacteriol. 195(19):4331-41. (2013) doi: 10.1128/JB.00502-13.

Ecology

The Mycobacterium tuberculosis forms a complex with other higher related bacteria called the M. tuberculosis complex that consists of 6 members: Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium africanmum, which infect humans; Mycobacterium microti, which infects vole; Mycobacterium bovis, which infects other mammalian species as well as humans; M. bovis BCG, a variant of Mycobacterium bovis and Mycobacterium canettii, a pathogen that infects humans. (7) M. tuberculosis first infected humans 10,000-15,000 years ago. (10) It has been found in early hominids originating in East-Africa. Therefore, studying the population structure of the species might provide insights about Homo sapiens' migratory and demographic history.

Once inside the human host cell, Mycobacterium tuberculosis inflicts a contagious-infectious disease called tuberculosis (TB), although the disease could either be latent or active depending on the ability of the person’s immune system to defend against the pathogen. In 1993, the World Health Organization declared TB a global public health emergency. It is estimated that one third of the world population is infected by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which leads to 8 to 10 million new cases, and 3 million deaths each year. (10) The disease especially affects those in developing countries, those of the aging population and those who have HIV/AIDs because of their weak immune system. (10)

Because TB is an infectious disease for humans, it is important to sequence the genome of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis in order to find drugs fight against the bacteria by developing potential drug targets. Especially since Mycobacterium tuberculosis is multi-drug resistance and could cause latent infection, it is especially hard to treat and prompts scientists to research for new drug targets by looking through the Mycobacterium tuberculosis genome and gene products.

Tuberculosis

The Disease

Tuberculosis (TB) is a disease caused by infection from the bacteria M. tuberculosis. If not treated

properly, TB can be fatal (1). Currently, the World Health Organization

estimates that over 13 million people have TB and about 1.5 million die each

year from the disease. Tuberculosis most commonly affects the lungs (pulmonary

TB). Patients with active pulmonary TB usually have a cough, an abnormal chest

x-ray, and are infectious. TB can also occur outside of the lungs

(extrapulmonary), most commonly in the central nervous, lymphatic, or

genitourinary systems, or in the bones and joints (1). Tuberculosis which occurs

scattered throughout the body is referred to as miliary TB. Extrapulmonary TB is

more common in immunosuppressed persons and in young children (2).

When a

person with active pulmonary TB coughs, sneezes, or talks, the bacteria that

cause TB may spread throughout the air. If another person breathes in these

bacteria, there is a chance that they will become infected with tuberculosis.

Repeated contact is usually required for infection (1). However, not everyone

infected with TB bacteria becomes sick. Roughly 5% of people infected with M.

tuberculosis actually develop TB. People who are infected but not sick have

latent TB infection. Those who have a latent infection are asymptomatic, do not

feel sick, and are not contagious.

Symptoms

Early symptoms of active pulmonary TB can include weight loss,fever, night sweats, and loss of appetite (1). Due to the vague initial symptoms of TB, an infected person may not feel that there is anything wrong. The infection can either go into remission or become more serious with the onset of chest pain and coughing up bloody sputum (3). The exact symptoms of extrapulmonary TB vary according to the site of infection in the body.

Transmission

TB is spread through the air from one person to another. Microscopic droplets that contain the bacteria may be expelled when a person who has infectious TB coughs or sneezes. They can remain suspended in the air for several hours, depending on the environment. When a person breathes in M. tuberculosis, the bacteria can settle in the lungs and begin to grow. From there, they can move through the blood to other parts of the body. TB in the lungs can be infectious because the bacteria are easily spread to other people. TB in other parts of the body, such as the kidney or spine, is usually not infectious (1). If a person has confirmed TB or is suspected of having TB, the best way to stop transmission is through immediate isolation. Therapy should

begin immediately. Contagiousness declines rapidly after a standard treatment regimen has begun, provided the patient adheres to the course of therapy.

Risk Groups

Anyone can get TB. However, some groups are at higher risk to get active TB disease. People at high risk include those (2):

1. with HIV infection

2. in close contact with those known to be infectious with TB

3. with medical conditions that make the body less able to protect itself from disease (for example: diabetes, or people undergoing treatment with drugs that

can suppress the immune system, such as long-term use of corticosteroids)

4. from countries with high TB rates

5. who work in or are residents of long-term care facilities (nursing homes, prisons, some hospitals)

6. who are malnourished

7. who are alcoholics or IV drug users

Infection

Infection can develop when a person breathes in tubercle bacilli from expelled droplets from an infected individual. The droplets reach the alveoli of the lungs where the bacilli can be deposited (4). Alveolar macrophages ingest the tubercle bacilli and destroy most of them. Some can multiply within the macrophage and be released when the macrophage dies. From there, the bacilli can spread to other regions of the body through the bloodstream. The areas in which TB is most likely to develop are: the apex of the lung, the kidneys, the brain, bones and lymph nodes. This process of dissemination prepares the immune system for a reaction (2).

In most infected individuals, the response from the immune system kills most of the bacilli. At this stage, a latent TB infection has been created, which may be

detected by using the Mantoux tuberculin skin test (see below). Within weeks after infection, the immune system is usually able to halt the multiplication of

the tubercle bacilli, preventing further progression. Most people recover completely from an initial infection, and the bacteria eventually die off

(3,4). In some people, the tubercle bacilli overcome the defenses of the immune system and begin to multiply, resulting in the advancement to active TB

disease. This process may occur shortly after infection or several years later (5).

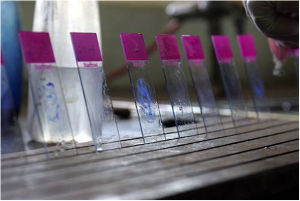

Diagnosis

The Mantoux tuberculin skin test, also known as the PPD (purified protein derivative) test, is used to detect TB infection. It is performed by injecting a small amount of tuberculin, a complex of purified M. tuberculosis proteins, into the skin of the arm. The reaction formed on the arm

determines the result of the test. A positive reaction for TB infection only

reports that a person has been infected with TB bacteria. It does not tell

whether or not the person has active disease. Other tests, inclluding a chest

x-ray and a sample of sputum, are needed to determine whether the person has

active disease(6). In pulmonary TB, lesions on x-rays are often seen in the apical segments of the upper lobe or in the upper segments of the lower lobe. However, lesions may appear anywhere in the lungs, especially in HIV-positive and other immunosuppressed persons (1).

An abnormal chest x-ray may indicate TB infection which is then confirmed or not by additional tests. Chest x-rays may be

used to rule out the possibility of pulmonary TB in a person who has a positive

reaction to the tuberculin skin test and no symptoms of disease. Persons

suspected of having pulmonary TB generally will have sputum specimens examined

by acid-fast bacilli smear and culture. Detection of acid-fast bacilli in

stained smears examined microscopically may provide the first clear evidence of

the presence of M. tuberculosis. Positive cultures for M.

tuberculosis are used to confirm the diagnosis of TB (6).

Stained slides of sputum smears ready for microscopy.

World Lung Foundation 2006

Treatment of Tuberculosis

M. tuberculosis is a very slow-growing, intracellular organism. Consequently, treatment requires the use

of multiple drugs for several months (5). With appropriate antibiotic treatment,

TB can be cured in most people. Treatment usually combines several different

antibiotic drugs that are given for at least 6 months, sometimes for as long as

12 months. However, many M. tuberculosis strains are resistant to one or

more of the standard TB drugs, which complicates treatment greatly

(3)

Currently, there are 10 drugs approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of TB. Of the approved drugs, isoniazid (INH), rifampin (RIF), ethambutol (EMB), and pyrazinamide (PZA) are considered

first-line antituberculosis agents. These four drugs form the foundation of

initial courses of therapy

Drug-resistant TB is major problem for the treatment of the disease. Multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB), is defined as disease

caused by TB bacilli resistant to at least isoniazid and rifampicin, the two

most powerful anti-TB drugs (7). MDR-TB is intrinsically resistant to drugs but

its resistance can be exacerbated by inconsistent or partial treatment. When

patients do not take all their medicines regularly for the required period

because they start to feel better, drug-resistant bacteria can arise. While

drug-resistant TB is generally treatable, it requires extensive chemotherapy (up

to two years of treatment) with second-line anti-TB drugs. These second line

drugs produce more severe adverse drug reactions more frequently than the

preferred first line drugs. There are six classes of second-line drugs used for

the treatment of TB

1. aminoglycosides

2. fluoroquinolones

3.

polypeptides

4. thioamides

5. cycloserine

6. p-aminosalicylic

acid

Within the last few years a new form of TB has emerged, extensively

drug-resistant TB (XDR-TB). Whereas regular TB and even MDR TB progress

relatively slowly, XDR TB progresses much more rapidly and can be fatal within

months or even a few weeks. XDR-TB is defined as TB that has developed

resistance to at least rifampin and isoniazid, as well as to any member of the

fluoroquinolone family and at least one of the aminoglycosides or polypeptides.

The emergence of XDR-TB, particularly in settings where many TB patients are

also infected with HIV, poses a serious threat to TB control (7).

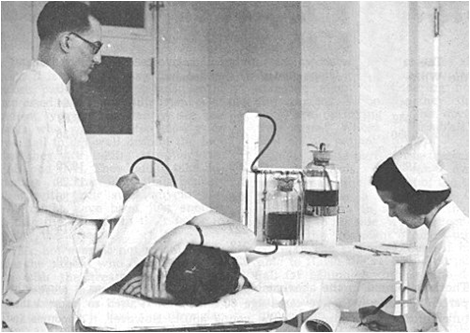

Currently, short course Direct Observation Therapy (DOTS) is a key component of the World

Health Organization's campaign to stop TB. DOTS involves patient case management

by trained health professionals who ensure that the patient is taking his/her TB

drugs (7,8). Because TB has such a long course of treatment, many patients stop

their medications prematurely. DOTS sends health professionals to the patient to

ensure s/he is taking the medication and may also supply the medicine to the

patient. In some areas, patients come to the DOT clinic instead of the health

worker traveling to them (7,8). Often, DOTS provides enablers or incentives to

ensure patients continue their treatment, such as transportation or free meals.

DOTS also tries to support TB patients (7,8). DOTS has been extremely successful

at decreasing the default rates, with cure rates above 80% and default rates

less than 10% (8).

Supervision of drug administration

in the TB hospital in

Benin, Africa

(www.WorldLungFoundation.org)

Prevention

TB is largely a preventable disease. Isolation of patients and adequate ventilation are the

most important measures to prevent its transmission in the community. In the

United States, healthcare providers try to identify people infected with M.

tuberculosis as early as possible, before they have developed active TB.

In those parts of the world where the disease is more common, the World

Health Organization recommends that infants and children receive a vaccine

called BCG (Bacille Calmette Guerin). BCG is made from live weakened

Mycobacterium bovis, a bacterium related to M. tuberculosis. BCG

vaccine prevents M. tuberculosis from spreading within the body, thus

preventing TB from developing.

BCG has drawbacks. It is reasonably effective

in preventing development of active disease in children. However, it does not

protect against TB in adults. In addition, BCG may interfere with the TB (PPD)

skin test, showing a positive skin test reaction in people who have received the

vaccine. BCG is used for children in countries where TB is endemic.

Consequently, much of the population would have a positive TB test regardless of

the vaccine. However, many countries where BCG vaccine is used have a limited

infrastructure and public health system Consequently, the problem is not as

important as it would be in countries without endemic TB (3).

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2009)

"Division of Tuberculosis Elimination (DTBE)", <HTTP: default.htm tb

www.cdc.gov>

2. American Lung Association (2009) "Tuberculosis (TB)" <HTTP:

content3.aspx?c="dvLUK9O0E&b=2060731&content_id={50031760-2D7C-4FFF-AD75-4C49BDD1CD7D}¬oc=1"

nlnet apps site www.lungusa.org>

3. National Institute of Allergy and

Infectious Diseases (2009), "Tuberculosis (TB)"

http://www3.niaid.nih.gov/topics/tuberculosis/

4. Harries A.D. and C. Dye

(2006) "Tuberculosis," Ann Trop Med Parasitology 100:415-431.

5. Goodman A, and M. Lipman (2008) "Tuberculosis," Clinical Med.

8:531-534.

6. Nahid P., M. Pai and P.C. Hopewell (2006) "Advances in

the diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis," Proc Amer Thoracic Soc

3:103-110.

7. World Health Organization (2009) Tuberculosis (TB)

http://www.who.int/tb/en/

8. Frieden, T.R. and J.A. Sbarbaro (2007)

"Promoting adherence to treatment of tuberculosis: The importance of direct

observation," Bull World Health Org. 85 2007, 325-420.

http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/85/5/06-038927/en/index.html

The Sanatorium Movement for Treatment of Tuberculosis

Until the discovery of tubercle bacillus, tuberculosis was primarily treated in the home. There was no

effective treatment. Doctors prescribed a variety of treatments including snake

oil and wearing a beard (1). However, in the mid-1800s, physicians began

recommending moving to temperate climates with clear air and a new treatment

regimen was born. The sanatorium made its first appearance in the 1850s in

Germany. The idea was developed by Herman Brehmer after he was apparently cured

by living in the Himalayan climate (2). Contributing to the development of

sanitoria was a developing fear of the spread of the disease, due in part to the

ability to detect the bacterium. Particularly in American, the success of

institutionalized treatments in Germany led to construction of sanatoria across

the United States. Sanatoria treatment was generally however reserved for the

middle and upper class due to the costs associated with providing the 24-hour

care, surgeries, and resort-type activities found at these institutions.

The Prince Albert Sanatorium was the largest

and most modern sanatorium in Saskatchewan;

it opened in 1930 at Prince Albert, Saskatchewan

(Valley Echo 34:30 (1953).

Part of the idea behind sanatoria was to assuage the societal pressure for

the isolation of those infected ensuring public health while providing the

afflicted with therapeutic regimens, including patient education. Educational

programs taught the infected what was known about the disease, new health

habits, and how to live with and protect others (3). After treatment was

completed, sanatoria offered rehabilitation to assist patients in achieving a

satisfactory economic status. Rehabilitation involved slowly introducing

occupational therapy into the treatment regimen in order to identify a job that

was interesting for the patient while remaining appropriate for recovery.

Patients at sanatoria were categorized into treatment groups based on the

seriousness of their infection. These treatment groups ranged from

'absolute'-meaning complete bed rest to 'graded'-allowed work and exercise.

Preliminary treatment for tuberculosis involved following two rules (4):

1. Absolute and utter rest of mind and body-no bath, no movement except to toilet

once a day, no sitting up except propped by pillows and semi-reclining, no deep

breaths.

2. Eat nourishing food and have plenty of fresh air

A tuberculous mother, on strict bed rest,

leaves her room at the sanatorium

for a Sunday walk with her family.

But she does not leave her bed

(Valley Echo 11:17 (1930).

The majority of sanatoria were built in the country because it was believed that the country

air aided in recovery. Patients were encouraged to leave the pestilential cities

and take in the fresh air and sunshine (1). A woman sent to a sanatorium in

England in 1945 described it as a "really nice atmosphere" with great meals and

a friendly staff (5). The Essex Sanatorium complex in New Jersey included a

state of the art hospital, cottages for patients, an auditorium and chapel. Many

facilities also included farmland that was used to provide tuberculosis patients

with fresh food and milk. A typical day in the life of a tuberculosis patient in

a sanatorium was (6):

1. Breakfast

2. Sitting or laying on a screened

porch for fresh air

3. Lunch

4. Sitting or laying on the porch-visiting

hours

5. Dinner

6. Bedtime

Bethesda Sanatorium

c1920. Interior view of balcony wing,

Bethesda Sanatorium, Denver, Colorado

( Photo by Louis Charles McClure, 1867-1957

www.hellodenver.com/Photos_People.Cfm)

This schedule varied for patients in recovery and would be modified to include 1-4 hours of exercise, activity, or

work. The social structure of sanatoria could resemble a prison, boarding

school, or resort depending on the location, staff, and the personal feelings of

the patients. Some patients felt like prisoners in the sanatorium due to all of

the restrictions on their activity while others enjoyed the relaxation and

outdoors. The healthier patients oftentimes would form clubs or 'gangs' that can

be compared University Greek organizations. These groups provided distractions

for the patients and a close network of friends during the isolation at the

sanatorium (2). The clubs were often very elitist and wary of outsiders; most

required membership dues and a demonstration of loyalty before a person would be

admitted. Groups such as these were extremely prevalent in European sanatoria

but were less evident in the later American establishments.

A sanatorium patient receives pneumothorax treatment

from Dr. GH Hames in Saskatchewan during the 1940s

(Valley Echo 40:21 (1959))

Recovery in the sanatoria setting depended largely on the stage of disease at admission; early diagnosis was essential for the treatments of the times (3). Stays at the sanatorium could last from months to years depending on the success of treatment and the willingness of the patient to follow the regimen rules. Discharge only

became a possibility after three negative sputum smears and a negative culture

(7).

The decline of sanatoria began with the scientific strides in the

treatment of tuberculosis, particularly after the discovery of antibiotics (2).

The responsibility for recovery shifted from patients to doctors with the

introduction of antibiotic treatment. Patients were no longer required to adjust

their lifestyle, personal habits, or mentality for recovery (1). The advent of

streptomycin after 1950 caused the number of patients requiring treatment

declined so drastically that sanatoria around the nation were abandoned. Many of

these facilities were converted to mental asylums or geriatric centers; others

were demolished.

References

1. Tulloch, M., "Tuberculosis." Blue Ridge Sanatorium, http://www.faculty.virginia.edu/blueridgesanatorium

2.

Condrau, F. (2001) 'Who Is the Captain of All These Men of Death': The Social

Structure of a Tuberculosis Sanatorium in Postwar Germany," J Interdisc

Hist 32: 243-263.

3. Bobrowitz, I.D. (1940) "Sanatorium Treatment

of Tuberculosis." Chest 6: 278-280.

4. Hurt, R. (2004)

"Tuberculosis sanatorium regimen in the 1940s: a patient's personal diary," J

Royal Soc Med 97:350-353.

5. "History of the Essex Mountain

Sanatorium http://www.mountainsanatorium.net

6. Bayne, R. (1998) "Ascending

the Magic Mountain," Can Med Assoc J 159:517-8.

7. Riehl,

E.D., G. Bereznicki, G. Rogers, R. Reza and J. Eagan (1977) "An Integrated

Approach to Tuberculosis Care in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania," Amer J

Publ Health 67:162-164.

Exploring the relationship between tuberculosis and nutrition

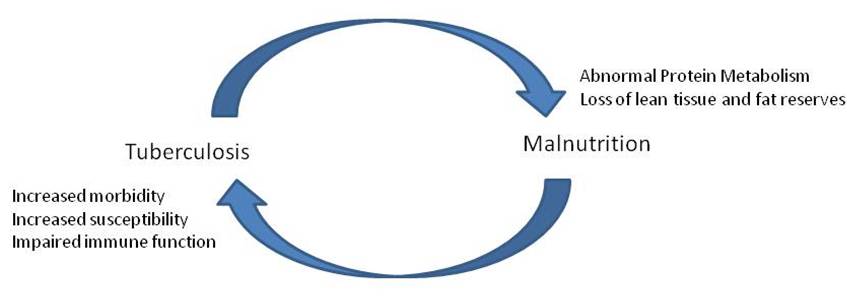

The relationship between tuberculosis and nutrition is complex and bi-directional (1). It is clear that individuals who

are malnourished are more susceptible to TB infection or to a latent infection

becoming active. TB infection also decreases the nutritional status of the

patient. However, because TB decreases the nutritional status of a patient, it

is difficult to accurately determine what the patient's nutritional status was

before TB infection and to conclude whether malnutrition or infection came

first. Regardless of cause and effect, 34% of TB cases are associated with

malnutrition, making malnutrition the second highest risk factor for active TB

after HIV (2). In a malnourished individual, TB may present atypically, causing

difficulty in diagnosis and longer periods before treatment (4). Similarly,

protein energy malnutrition has been found to decrease the effectiveness of the

tuberculin skin test because of decreased immune response (3).

Redrawn from

(1): Bidirectional interaction of tuberculosis

and malnutrition and some

putative mechanisms

How does nutrition affect the risk of getting TB?

Malnutrition has been linked with decreased immune function in

multiple studies in diseases unrelated to TB (1). Cell mediated immunity is the

body's way of keeping TB latent, but if a patient is malnourished, his or her

immune status is lower; consequently, the risk of progression to active TB

increases (3). Some argue that malnutrition is not actually a risk factor for

active TB, but that the same risk factors for malnutrition are risk factors for

TB, most commonly, poverty (3). In many countries, even HIV negative patients

without TB are underweight so it is difficult to say if malnutrition is a risk

factor for TB or just a fact of life in those countries that are commonly

affected by TB.

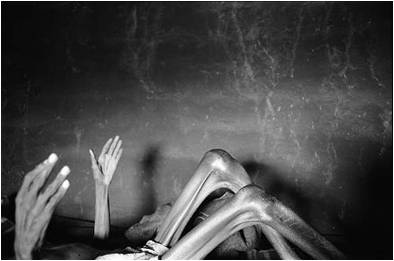

A severely malnourished individual

(World Lung Foundation,

2006)

How does TB change the patient's nutritional status?

During active TB infection even well-fed patients have altered protein metabolism (1).

A patient with active TB uses less protein to build up muscle, leading to

increased oxidation of amino acids and increased oxidative stress that the body

has to fight. Reduced antioxidant intake (vitamins A, C, and E) causes a

decrease in the body's immune response and also means that oxidant and free

radical induced damage and inflammation increases (5). The combination of poor

amino acid utilization and low antioxidant intake may lead to the exacerbation

of active TB or make the patient more susceptible to develop active TB from a

latent infection. It is difficult to say which is cause and effect. Anemia is

common in TB patients, but iron overload causes oxidative stress may exacerbate

the disease (5). The risk of increasing a patient's oxidative stress levels

makes treating TB related malnutrition more difficult.

Active TB increases a patient's resting energy expenditure, which leads to wasting if extra calories

are not provided in the diet (1). Interestingly, in the wasting of TB, women

seem to lose fat while men lose lean (muscle) tissue (6). In a study in Malawi,

69% of active TB patients had a BMI (body mass index, metric weight/metric

height2) less than 19 (4). A BMI less than 19 is considered

underweight, while a BMI under 17 is considered severely underweight (see

below). The Malawi study also found that a lower BMI was correlated with a more

advanced TB infection. HIV negative adults with extremely advanced TB infection

had a mean BMI of 17 (4). In another study, a BMI of 17 or less meant the

individual had twice the risk of early death associated with TB (5). Individuals

who were 10% below their ideal body weight were three times more likely to

become infected with TB than those who were 10% above their ideal body weight

(3). )

| Classification | BMI |

| Underweight | <19 |

| Normal Weight | 19-25 |

| Overweight | 25-30 |

| Obese | >30 |

From http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/obesity/BMI/bmicalc.htm

Unfortunately, TB patients often want to eat less than healthy people, making it even more difficult to

prevent wasting or to rebuild body stores (5). HIV co-infection particularly

causes a decrease in patients' appetites, and also brings nutritional indicators

down even more. Thus, nutrition and supplementation in co-infected individuals

must be closely monitored and constructed (5). It can take at least 12 months

for patients to build up their body stores after TB infection (1). Often, this

is difficult if they return home because they are likely to return to work

(expending more energy), and their diet may be poorer and less balanced than at

a care facility (1).

One nutritionally related aspect of immunity is the finding that vitamin D deficiency may increase the risk of infection and/or progression to the active form of the disease. This is because vitamin D is

critical for macrophage activity (4). Another specific nutrition related concern

is vitamin A deficiency, which has been linked to chronic infections and

infection with HIV (7). In a study of TB patients and controls who were HIV

positive and negative, the lowest vitamin A levels were found in patients with

HIV and TB co-infections. After two months of TB treatment, HIV negative

patients had increased vitamin A levels while those with the HIV co-infection

had decreased vitamin A levels (7). This may be related to the changes in

protein metabolism noted above since vitamin A loss is associated clinically

with protein losses, while protein rich diets increase levels of Vitamin A (7).

How does nutritional therapy help cure active TB or reduce the risk of TB infection?

When protein energy malnourishment is reversed, treatment of TB

is more effective (3). However, when TB is treated and patients begin gaining

weight, it is usually fat mass that increases, not lean mass (5). Thus, specific

nutrition therapy strategies need to be developed to increase patients' lean

mass. Protein supplementation may increase the patient's restoration of lean

mass, although this can take more than 12 months (5).

Vitamin rich cod liver oil was a common early treatment for TB (5), and vitamin A supplementation

during treatment may speed the patient's initial recovery and decrease their

infectiousness more quickly (5). Vitamin supplementation for family members of

active TB patients may decrease their risk of acquiring active TB (3).

Policy and Treatment Implications for Malnutrition in TB

Because nutrition can help with the prevention of active TB infection, it is important

that policies of governmental or other agencies targets the problem underlying

malnutrition: poverty (2). All malnourished individuals are considered at risk

for TB. Food security is a major goal for such people, not just the severely

malnourished ones. Malnutrition often continues after treatment, and low weight

correlates with TB relapse (5), so policy must be put in place to increase food

security and nutrition for those who have been cured of active TB.

Because TB is so infectious, treatment is a community problem. Providing adequate

nutrition to malnourished individuals helps the entire community. Unfortunately,

in nations with endemic TB, food comes from small community farms, TB can also

create a cyclical problem because it eliminates workers from crucial activities

like farming, creating increased hunger and increased susceptibility to active

TB in a community (5).

Providing food can encourage people to come for treatment, so it can be an effective part of DOTS (5). However, programs that

have tried distributing food to patients encounter many questions about who

should get the food: should rations be provided only for patients, or should

food be provided for their families as well? It costs <$1 per day in many

developing countries to support an AIDS patient and their family with food, and

estimates put an equal price on supporting a TB patient and their family (5).

Providing food for the family as well as the patient may be important because

patients receiving food for themselves are likely to share the food with family

members, thus decreasing the amount the patient eats. Families have positive

perceptions of food aid, and believe it helps their relative recover.

File:TB-Picture5.png

Food aid for patients with TB

(www.WorldLungFoundation.org)

References

1. Macallan, D.C. (1999) "Malnutrition in Tuberculosis,"

Diag Microbiol Infect Dis 34:153-157.

2. Lonnroth, K., and M.

Raviglione (2008) "Global Epidemiology of Tuberculosis: Prospects for Control,"

Sem Resp Crit Care Med 29:481-491.

3. Cegielski, J.P., and

D.N.McMurray (2004) "The relationship between malnutrition and tuberculosis:

evidence from studies in humans and experimental animals," Int J Tuberculosis

Lung Dis 8:286-298.

4. Lettow, M.V., J.J. Kumwenda, A.D. Harries,

C.C. Whalen, T.E. Taha, N. Kumwenda, C. Kang'ombe and R.D. Semba (2004)

"Malnutrition and the severity of lung disease in adults with pulmonary

tuberculosis in Malawi," Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 8:211-217.

5.

Papathakis, P. and E. Piwoz (2008) "Nutrition and Tuberculosis: A review of the

literature and considerations for TB control programs," USAID: Africa's Health

in 2010 project, http://www.aidsportal.org/Article_Details.aspx?ID=7931

6.

Swaminathan, S., C. Padmapriyadarsini, B. Sukumar, S. Iliayas, S.R. Kumar, C.

Triveni, P. Gomathy, B. Thomas, M. Matthew and P.R. Narayanan (2008)

"Nutritional Status of Persons with HIV Infection, Persons with HIV Infection

and Tuberculosis, and HIV-Negative Individuals from Southern India," Clin

Infect Dis 46:946-9.

7. Mugusi, F.M., O. Rusizoka, N. Habib and

W. Fawzi (2003) "Vitamin A status of patients presenting with pulmonary

tuberculosis and asymptomatic HIV-infected individuals, Dar es Salaam,

Tanzania," Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 7:804-807.

HIV and TB

Introduction

It is estimated that a third of the 36 million people on the planet with HIV/AIDS are infected with M. tuberculosis (1). This co-infection has been dubbed the "cursed duet," draining approximately 30%

of the annual income of an infected household in both direct and indirect costs,

becoming a social and economic disaster for families (2).

The countries with the highest TB/HIV co-infection rates continue to be in Sub-saharan Africa,

where HIV is ravaging the population. One example is Zambia. It's TB rates were

stable in the 1960's and 1970's, but the number of TB cases quadrupled as HIV

spread across the country (3). Worldwide, the largest increase in co-infection

with TB and HIV has occurred in the 25-44 year old population range (4). Since

this age group is generally so active in the workforce, the consequent economic

impact is huge.

A TB patient who is infected with HIV has lost

over half his

body weight

(www.WorldLungFoundation.org)

Co-Infection

Why is co-infection so common? HIV infection is commonly listed as the highest

risk-factor for becoming infected with TB, as well as greatly increasing a

person's risk for developing active tuberculosis. Because HIV/AIDS depletes the

immune system, opportunistic infections become serious problems. (An

opportunistic infection is an infection that is kept under control in an

immuno-competent person, but becomes too much for the immune system when

infected with HIV.) People with healthy immune systems can become infected with

TB but only about 5% develop active disease. In the population with latent TB,

the infection may lie dormant for years, becoming active disease only when the

body's immune system is weakened, as occurs with HIV infection (2).

Once latent TB resurfaces in an HIV-positive patient, it can move from the lungs to

other organs more rapidly than in patients without HIV infection. This is known

as extrapulmonary TB. As it moves into other organs and tissues, it causes

irreversible damage. With time, more systems become involved with the

extrapulmonary TB, weakening them in turn and allowing the body to become

devastated with increasing speed. These weakened systems allow the HIV to

progress more rapidly, greatly expediting both disease processes and greatly

decreasing life expectancy (2).

Treatment and Related Issues

Medical treatment of TB and HIV/AIDS is extremely complicated due

to several severe medication interactions, often malnutrition and conflicting

disease processes. Treatment for TB always takes precedence over HIV/AIDS

treatment due to TB's infectious nature through the air. However, with

antiretroviral therapy taking a backseat to TB, the HIV infection may progress

more quickly, weakening the immune system even more rapidly. This makes it

easier for opportunistic infections to take over, putting more stress on the

patient's body, lowering life-expectancy (5).

The anti-TB drug thiacetazone can cause serious,

sometimes fatal, side effects in many HIV-positive patients

(www.WorldLungFoundation.org)

A major issue affecting treatment of HIV/TB Co-infection is the potential cost of treatment. The preferred treatment for HIV

is highly active combination anti-retroviral therapy. While these drugs are very

effective at slowing the progression of HIV to AIDS, they are expensive,

especially for people in developing countries. Adding the cost of the common

antibiotics used to treat TB moves the price of medication out of reach for even

more people (6). Further complicating the problem is that the co-infection and

weakened immune system makes the patients more susceptible to adverse drug

reactions from potentially quite toxic drugs.

The stigma associated with both diseases is another major issue surrounding diagnosis and treatment of both HIV

and TB. The stigma of the separate and combined diseases is intertwined with

disease perception. Many consider the TB of co-infection with HIV to be a new

disease, since "the TB of today should be given another name because it doesn't

cure" (7). In many developed countries, the TB of the past was viewed as a

curable, relatively simple infection that was acquired in more mundane ways like

"men smoking tobacco or marijuana," or "drinking home brewed liquor." In

contrast, new TB is acquired though "hanging out in bars" and "sexual

transgressions" (7). When someone is diagnosed with TB, their past behavior is

often viewed as improper, immoral, with a consequent judgment passed about how

the person contracted HIV/TB. These judgments can be reinforced by moral

judgments from religious leaders, since "Satan is these two diseases"

(7).

This problem with TB is compounded by the presence of HIV, which has

been highly stigmatized since it exploded in the 1980's. The most common ways to

transmit HIV are through intimate sexual contact and blood-to-blood contact from

transfusions or sharing needles, which is common among injection drug users.

Thus, HIV infection is commonly associated with unprotected sex and drug use.

In many parts of the world, TB and HIV are both so common and occur together

so often that the distinctions between the two diseases are obscured, creating

the need to create a new label for the joint stigmatization faced by patients.

Further compound the TB-HIV stigma is the misinformation surrounding treatment

of both diseases. People with active cases of TB are considered most contagious

for the first 2-3 weeks of treatment. Close contact should be avoided during

those weeks; however, misinformation often leads to exaggerated fears about

contracting the disease, causing prolonged physical and social isolation

(7).

One positive aspect is that concurrent testing for HIV and TB is

becoming an increasingly common intervention at HIV treatment centers worldwide.

Previously, neither HIV nor TB clinics commonly tested for the other disease.

While the disapprobation surrounding both diseases can make dual testing

difficult, it is an important step in reducing the number of co-infections.

Early detection of TB/HIV infection and early treatment can help to reduce the

severe effects of co-infection on the body's immune system, increasing life

expectancy. The sooner a person begins treatment for TB, the less chance they

have of infecting others, and the sooner they are aware of their HIV positive

status, the more they are able to limit their high-risk behavior, providing less

chances to infect others with HIV (6).

References

1. Colebunders, R. and M.L. Lambert 2002) "Management of co-infection with HIV and TB: Improving

tuberculosis control programmes and access to highly active antiretroviral

treatment is crucial" Brit Med J 324:802-803.

2. Sharma, S.K.,

A. Mohan, and T. Kadhiravan (2005) "HIV-TB co-infection: Epidemiology, diagnosis

and management," Ind. J Med Res 212:550-567.

3.

Godfrey-Faussett, P. and H. Ayles (2003) "Can we control tuberculosis in high

HIV prevalence settings?," Tuberculosis 83:68-76.

4. World

Health Organization (2006) "Tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS - Some Questions and

Answers" http://www.searo.who.int/en/Section10/Section18/Section356/section421_1624.htm

5. Corbett, E.L., C.J. Watt, N. Walker, D. Maher, B.G. Williams, M.C.

Raviglione and C. Dye (2003). "The Growing Burden of Tuberculosis: Global Trends

and Interactions with the HIV Epidemic," Arch Intern Med

163:1009-1021.

6. Manosuthi, W., S. Chottanapand, S. Thongyen, A.

Chaovavanich, and S. Sungkanuparph (2006) "Survival Rate and Risk Factors of

Mortality Among HIV/Tuberculosis Coinfected Patients With and Without

Antiretroviral Therapy," J Acq Immun Def Syndrome 431:42-46.

7. Bond, V. and L. Nyblade (2006) "Importance of Addressing the Unfolding

TB-HIV Stigma in High HIV Prevalence Settings," J Comm Appl Soc Psych

16:452-461.

Application to Biotechnology

Gene for histone-like protein (hupB [Rv2986c]) of Mycobacterium tuberculosis had been used to distinguishing members of the MTB complex from other mycobacterium species and differentiating between members within the complex.

In addition, in vivo complementation in Mycobacterium tuberculosisstrain H37Ra can be used to identify genomic fragments associated with virulence. By studying the genes encoding for virulent gene products, a combination of drugs and vaccines could be developed to target the MDR and XDR characteristic of the pathogen.

Current Research

Since the pathogen-host interaction of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is still unknown, much of the current research is geared towards the understanding of the mechanism of virulence. For example, one such research showed that prokaryotic- and eukaryotic-like isoforms of the glyozxylate cycle enzyme isocitrate lyase (ICL) are jointly required for fatty acid catabolism and virulence in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. This discovery provides insight such as drugs that are glycoxylate cycle inhibitors could be used to treat tuberculosis. (12).

Another group of scientists found that a newly identified protein with carboxyesterase activity is required for the virulence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. They found that the gene MT2282 encodes a protein that is associated with carboxyesterase. It hydrolyzes ester bonds of the substrate. When a strain containing a mutant of this gene was used to infect mice, the mice’s life was prolonged as compared with those that were infected with the wild type strain. (5)

In addition, as mentioned earlier, very little is known regarding host-microbe interaction that happens before M. tuberculosis gets into the macrophages and how M. tuberculosis adheres to the host is still being researched. One research suggested M. tuberculosis produces tiny pili that enable them to colonize the host by adhering to the host and invading the macrophages and epithelial cells of the host. (1) The pili produced are called MTP. The study is important because MTP could be used as vaccine because MTP-mediated events are critical for TB infection. (1)

References

1. Alteri, C.J., Xicohtencatl-Cortes, J., Hess, S. Caballero-Olin, G., Giron, J.A., and Friedman, R.L. “Mycobacterium tuberculosis produces pili during human infection.” Microbiology 2007; 104(12): 5145-5150.

2. Aranaz A, Liébana E, Gomez-Mampaso E, et al. “M. Tuberculosis subsp. caprae subsp. nov.: a taxonomic study of a new member of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex isolated from goats in Spain. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1999; 49:1263 73.

3. Banaiee, N., Jacobs Jr, W.R., and Ernst, J.D. “Regulation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis whiB3 in the mouse lung and macrophages.” Infection and Immunity 2006; 74: 6449-6457.

4. Barksdale, L. and Kim, K. “Mycobacterium.” Bacteriological Reviews 1977; 41: 217-372.

5. Bishai, W.R., Lun, S. “Characterization of a novel cell wall-anchored protein with carboyesterase activity required for virulence in Mycobacterium tuberculosis.” The Journal of Biological Chemistry 2007; 1-22.

6. Chen, M., Gan, H., and Rernold, H.G. “A mechanism of virulence: virulent M. Tuberculosis strain H37Rv, but not attenuated H37Ra, causes significant mitochondrial inner membrane disruption in macrophages leading to necrosis.” The Journal of Immunology 2006; 176: 3707-3716.

7. Cole, S.T. “Comparative and functional genomics of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex.” Microbiology (2002); 148: 2919-2928.

8. Cole, S. T. , Brosch, R. , Parkhill, J. , Garnier, T. , Churcher, C. , Harris, D. , Gordon, S. V. , Eiglmeier, K. , Gas, S. , Barry, C. E. “Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence.” Nature 1998; 393(6685): 537-44.

9. Cosma, C. L., K. Klein, R. Kim, D. Beery, and L. Ramakrishnan. “Mycobacterium marinum Erp is a virulence determinant required for cell wall integrity and intracellular survival.” Infect. Immun. 2006; 74:3125-3133.

10. Ducati, R.G., Ruffino-Netto, A., Basso, L.A., Santos, D.S. “The resumption of consumption – A review on tuberculosis.” Rio de Janeiro 2006; 101: 697-714.

11. Manganelli, R., Voskuil, M.I., Schoolnik, G.K., and Smith, I. “The Mycobacterium tuberculosis ECF sigma factor sigmaE: role in global gene expression and survival in macrophages.” Mol Microbiol 2006; 41: 423– 437.

12. Munoz-Elias, E.J., McKinney, J.D. “Mycobacterium tuberculosis isocitrate lyases 1 and 2 are jointly required for in vivo growth and virulence.” Nat Med. 2005; 11: 638-644.

13. NCBI. 24 May 2007. Welcome Trust Sanger Insitute. 2 June 2007 <http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?db=genomeprj&cmd=Retrieve&dopt=Overview&list_uids=224>.

14. Riley, L.W. “Of mice, men and elephants: Mycobacterium tuberculosis cell envelope lipids and pathogenesis.” American Society for Clinical Investigation 2006; 116:1475-1478.

Edited by Ying Liu of Rachel Larsen and Kit Pogliano

KMG