Oral bacteria and cardiovascular health

Introduction

At first thought, our mouths and our cardiovascular system do not seem to be connected. However, our cardiovascular system is intertwined with our entire anatomy. Our gums have tiny blood vessels, automatically linking our mouth to our blood and subsequently, our heart. Oral disease and cardiovascular disease (CVD) are two incredibly prominent health issues in America. Oral disease and cardiovascular disease (CVD) are two incredibly prominent health issues in America. Oral diseases or periodontal diseases are caused by infections or inflammation of the gums.[1] One type of oral disease is periodontitis. It is an inflammatory disease of the tissues (gums). Another disease, gingivitis is an inflammation of the gingival sulcus which is the space between a tooth and gingival tissue. Lastly, dental caries include tooth decay, cavities, or general breakdown of teeth due to bacteria.[2] According to the CDC, 47.2% of adults who are 30 years or older and 70.1% of adults 65 years and older report having periodontal disease. Additionally, 56.4% of men report periodontal disease whereas 38.4% of women report it.[1]

Cardiovascular diseases are one of the leading causes of death for both men and women within the United States.[3] There are several types of heart disease including valvular heart disease, arrhythmias, hypertension, and atherosclerotic disease.[4] An estimated 560,000 people die due to CVD each year.[5] Other types of CVD include peripheral artery disease, congestive heart failure and stroke.[2]

Research in recent decades draws several connections between increased periodontal disease to increased risk of CVD.[4][6][7] There are several connecting factors such as systemic inflammation, bacteremia, and overlapping risk factors (i.e. smoking, diabetes, etc.).[8] Other studies done demonstrate reduction of certain markers of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Over the course of 6 months of periodontal therapy resulted in the lowering of c reactive proteins, improvement of endothelial function, and a lowering of carotid intima thickness.[4] C reactive proteins (CRP) are produced by the liver and found in blood plasma. Rising CRP levels indicate increasing inflammation or the beginning of an infection.[9] The endothelium is a very thin membrane that lines the inside of the heart and blood vessels. Endothelial cells are critical to heart function because they release substances that control the heart beat (contraction and relaxation) and enzymes that regulate blood clotting, immune function and platelet adhesion. Platelets or thrombocytes are blood cells that form bone marrow and play a major role in blood clotting. The ability to clot is critical to controlling any type of bleeding. Any dysfunction of endothelial cells can be an indicator of heart disease, more specifically is a precursor to atherosclerosis.[10][11] Similar to endothelial dysfunction, thickening of the carotid intima (the inner two layers of the carotid artery) also indicates atherosclerotic disease.[12]

Initial therapies and experiments have been conducted targeting periodontal disease that show a decrease in heart disease when there is a decrease in periodontal disease [8] By identifying and studying the correlating or possible causal relationships, therapies and preventative measures can be developed. Given the severity, prevalence and ramifications of cardiovascular disease and periodontal disease, it is vital to understand the nature of the relationship between the two health related conditions.

Oral Cavity Structure and Function

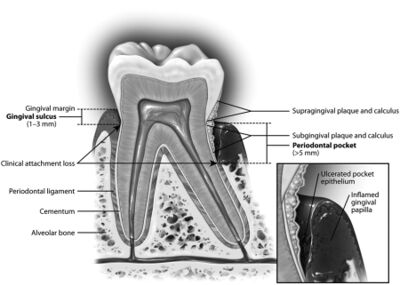

Our teeth are multilayered structures that connect to our jaw to form a functional relationship allowing us to chew, speak, and drink. The part of the tooth that we see when we open our mouth is the dental crown. It is covered by enamel, a tough bodily tissue that covers the surface. Below the surface is the tooth root.[13] Dentin is the tissue that makes up the tooth between the dental crown and the tooth root. It is within the enamel and cementum, however is not as tough as enamel.[13]

Cementum is a connective tissue on the surface of the tooth root. It attaches the alveolar bone with the tooth by the periodontal ligament which is mainly fibrous tissue and prevents injury to the alveolar bone while we chew. The alveolar bone is the jaw bone that supports the tooth that is implanted in it.

This structure is greatly affected by periodontal disease. Lastly are the gingiva and gingival sulcus. The gingiva is the soft tissue that surrounds the alveolar bone. It is commonly known as the gums. The gingival sulcus is a tiny space in between the tooth and the gums. This pocket grows due to inflammation. When it deepens, it is referred to as the periodontal pocket. [13]

Cardiovascular System

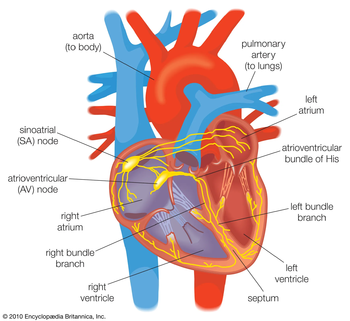

Our cardiovascular system is incredibly complex and central to our survival. It is fundamental to circulating oxygen and nutrients to our entire body and removing waste. It is made up of our heart and blood vessels distributed throughout our body.[14])

Our blood carries the oxygen, nutrients, and waste throughout our body. There are certain functions of the circulatory system such as vasodilation/vasoconstriction and coagulation. These functions play a role in maintaining the conditions of the heart. Especially vasodilation and vasoconstriction which affect blood pressure. Vasodilation and vasoconstriction are the widening and narrowing of blood vessels, respectively. When vasoconstriction occurs, blood flow to bodily tissues is limited and also results in increased blood pressure. High blood pressure can put undue stress on the heart.[15] Coagulation refers to the blood transforming into a semi-solid gel like state. This is the formation of a blood clot. To be able to clot is vital for survival. For example, if you scrape your knee and are bleeding, clotting occurs so that eventually, the bleeding will stop. This is critical so that people don’t bleed out anytime they get an injury (internally or externally).[16]

The heart constantly works to circulate thousands of gallons of blood every day. Veins bring blood to your heart while arteries carry blood away.[14] Coronary arteries bring oxygenated blood to the muscle of the heart. These arteries wrap around the entire outside of the heart.[17]. Another important artery is the carotid artery. This is a major blood vessel that is responsible for transporting both blood and oxygen to the brain.[18]

Two important circulation processes are pulmonary circulation and systemic circulation. Pulmonary circulation brings blood without oxygen that enters the right side of the heart to the lungs to be oxygenated and ensures the removal of carbon dioxide (waste). The now oxygenated blood enters the heart again through the left side. Systemic circulation takes the newly oxygenated blood that just reentered the left side of the heart out to the rest of the body’s cells to receive oxygen and nutrients.[14]

Cardiovascular Disease

As mentioned, there are several categories of heart disease. Cardiovascular disease is classified as any disease pertaining to the cardiovascular system outlined above. This includes disease of the coronary arteries, carotid artery, or peripheral arteries. Causes of heart disease can be environmental or genetic. Certain lifestyle choices can be beneficial to preventing heart disease such as increased exercise, reduced salt or fatty food intake, and not smoking.[19] Specifically looking at atherosclerosis, a disease of the arteries that is due to a buildup of plaque and fatty material, there is a clear increase in incidence with patients that also have chronic inflammatory diseases such as periodontitis.[8][19] Plaque consists of white blood cells (which are launched as an immune response), fatty substances, and cholesterol.[19]

There are certain biomarkers (a measure of what is happening within a cell at a certain time) that indicate heart disease. [20][21] These biomarkers include low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and C-reactive proteins (CRP). The presence of these biomarkers indicates the activation of pathways that indicate an infection.[20] Lipoproteins transport cholesterol which is a fatty substance in the blood. [22] There are two types of lipoproteins: high density lipoprotein (HDL) and low density lipoproteins (LDL). HDL is often referred to as good cholesterol and LDL bad cholesterol. [22] High levels of LDL is a major indicator of atherosclerosis. [23] The ingestion of LDL causes lipid oxidation resulting in the formation of and accumulation of lipid products in the arterial vascular wall. High CRPs can be a predictor of future strokes or systemic arterial hypertension. They indicate that there is an infection or increased inflammation. They also play a role in endothelial cell dysfunction which as previously mentioned are essential for regulating the heart.[8] [10]

Another type of cardiovascular disease is infective endocarditis (IE). Infective endocarditis is the result of a bacterial infection on the endocardial surface of the heart [24] The endocardium is a smooth and thin tissue that lines the chambers and valves of the heart.[25] There is an interaction between bacteraemia and the endocardium. Bacteraemia is an infection of the bloodstream (usually due to the presence of bacteria).[25] Invasive or pathogenic microorganisms and host immune system interaction with bacteraemia sometimes results in infection, affecting the endocardial tissue composition. Typically, the valvular endothelium resists bacterial colonization. However, with IE, the tissue is modified which produces a site for bacterial attachment and subsequently bacterial colonization.[25]

Connecting Oral Disease and Bacteria

From brushing our teeth to breathing or eating, our mouths regularly encounter an enormous amount of bacteria. There are hundreds of healthy bacteria existing in the oral cavity. [7] [26] An equilibrium exists between the healthy bacteria and the host defense system. Biofilms are tough clusters of bacteria that stick to layers of substrates. These types of biofilms are not easily removed by an immune response.[27] Gingival crevicular fluid serves as the nutritional source of carbon and nitrogen for bacteria found in periodontal pockets. T cells and B cells show fast responses against foreign substances/invaders.[27] T cells are unable to respond to polysaccharide antigens like glycolayx (a biofilm matrix). As a result, the immune response of the host cells is not sufficient to eliminate biofilm matrix antigens. Specific antibodies are able to eliminate biofilm, but only on the surface of bacterial cells in dental plaque. For example, phagocytosis can eliminate the bacteria found on the surface of biofilms. However, phagocytic cells cannot kill the bacterial cells within the biofilm. As a result, there are persisting infections existing in the subgingival regions.[27]

Dental plaque has adapted to favor survival in this environment since the host cells contain adaptive immune response in an attempt to limit plaque growth.[26] Combinations of certain microbial species or if the host lacks an adaptive immune response can cause damaging inflammation. The bacteria releases antigens which the host recognizes as foreign or invasive species and triggers the immune response to limit further growth.[26] The formation of dental plaque results in pellicles forming which allows bacteria such as Streptococcus gordonii to bind to protein rich regions found in the pellicle. This is an example of a bacteria that when bound in excess, can cause harmful inflammation. [26] Periodontitis begins with a microbial infection and can cause immunological responses that elevate levels of serum immunoglobulin antibodies against bacteria.[7] Infecting bacteria include Porphyromonas gingivalis, Tannerella forsythia, Streptococcus oralis, and Staphylococcus epidermidis. S. oralis exists as a common oral bacteria, but can become pathogenic. Pathogenic means that a bacteria or other microorganism causes a certain disease.[28]

Following the initial microbial infection, the soft tissues are attacked by hyperactivated leukocytes and the generation of cytokines. Leukocytes are a type of white blood cell that travel within the blood and counteract foreign substances such as disease.[29] Cytokines can cause connective tissue and bone destruction.[7] [30], Neutrophils play a role in the immune response. They factor into the host response against periodontopathogenic microorganisms. If bacterial biofilms are not disrupted such as they are when we brush our teeth, ecologic changes occur like the the development of a small set of gram-negative anaerobic bacteria (like P. gingivalis) develops. This then triggers the host immunoinflammatory process in an attempt for bacterial removal. [30] The epithelium within the gingival sulcus communicates with bacteria found in the subgingival crevicular space. This interaction causes and transmits signals between the bacteria and nearby immune cells. If there is an increase in bacteria, it can cause the increase of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines. These recruit cells that are involved in the immune and subsequent inflammatory response (increase in dendritic cells, T and B cells, macrophages, and neutrophils).[8]

Linking Oral Disease and Cardiovascular Disease

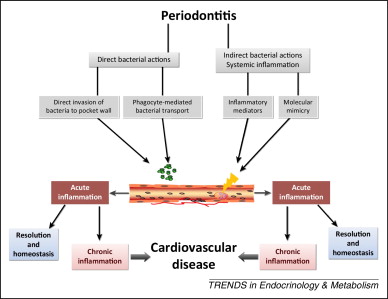

While seemingly separate health conditions, there is great evidence directly and indirectly linking oral health to cardiovascular health. As previously mentioned, periodontitis is an inflammatory disease that affects the tissues that support teeth due to plaque build up.[2] Plaque is a microbial biofilm that forms on the surface of teeth. It enables bacterial populations to adhere to surfaces and each other. A pellicle can result from plaque build up. A pellicle is a film of proteins found in saliva that enhances bacterial attachment.[26] Significant plaque formation results in continual deposition of bacteria and cell surface components into the oral cavity and gingival sulcus. The gingival sulcus ends up being a portal for bacteria into the bloodstream.[26] P. gingivalis along with other bacteria demonstrate invasion of coronary artery cells. P. gingivalis specifically degrades epithelial cell junctional complexes and proteins, including the vascular epithelium.[8][27] Atherosclerosis is a disease of the arteries due to a build up of fats and cholesterol on their walls. Periodontitis results in significant plaque formation which breaks off and through endothelial tissues enters the bloodstream. This demonstrates how periodontitis can factor into the development of atherosclerosis.[2] Patients with atherosclerosis also demonstrated higher levels of periodontitis. Bacteria found in periodontal pockets have also been linked to atherosclerosis via a sample of the plaque formed in the arteries.

Dental plaque bacteria that form biofilms are able to enter the bloodstream causing bacteremia.[27] Bacteremia is the presence of bacteria circulating in our blood.[2] For example, Streptococcus sanguinis, the streptococcus species most commonly found in dental plaque forms biofilms. It is often localized in blood. Together, this indicates that dental plaque is a cause of bacterial infections in the bloodstream.[27] In tandem with bacterial translocation originating in periodontal injury, bacteremia is one instance of invasion of bacteria into cardiovascular tissue. Since periodontitis is an inflammatory disease, it can result in systemic inflammation. This causes additional stress on the cardiovascular system. Increased systemic inflammation is a common marker of both periodontitis and atherosclerosis. It results in the chronic elevation of inflammatory markers.[4] This includes the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines resulting from infection and inflammation of the gums.[20] P. gingivalis, a bacteria that results in the infection of the gums, causes increased elevation of c-reactive proteins, upregulating systemic inflammation factors even more.[20]

Phagocytes (a type of cell that can engulf bacteria) containing oral bacteria promote the growth of atheroma which is plaque deposits in arteries, increasing risk of CVD such as atherosclerosis. Any damage or inflammation allows bacteria to enter our circulatory system. In certain studies, evidence of periodontal bacteria was found in affected cardiovascular tissue, demonstrating that it can reach systemic vascular tissue. [2] Specifically, periodontal pathogens have been found on carotid atheromatous plaques, a result of artherotisis. [31]

The release of pro-inflammatory cytokines stemming from inflamed periodontal tissue causes increased resistance to insulin.[11] Mainly, insulin manages glucose levels in the blood. It also mediates vasodilation and blood clotting.[32] Production of insulin triggers the synthesis of nitric oxide (NO). This then causes the release of NO from vascular surfaces resulting in vasodilation.[33] If there is increased resistance to insulin, there is an increase in glucose levels found in blood. Higher glucose levels can cause hyperactivation of platelets causing higher rates of clotting.[34]For these reasons, changes in insulin resistance causes changes in hypercoagulability and vasodilation as a result. Platelets play a functional role in blood clotting. As cited above, clotting is essential to stopping bleeding.[16][11] With heart disease, there is increased platelet activity i.e. too much clotting (hypercoagulability) can occur resulting in blockages.[20] Also caused by heart disease is an increase in reactive oxidative species (ROS). ROS are associated with both periodontitis and CVD. Higher levels of ROS upregulates the oxidation of LDL cholesterol.[20] As discussed in the cardiovascular disease section, LDL cholesterol is a major factor of atherosclerosis.[22] Periodontal disease affects oxidized LDL also as a result in the increase of ROS. Oxidized LDL is central in the pathogenesis of atherosclerotic plaque.[20] Mainly, the increased inflammation, changes in vasodilation, and resulting resistance to insulin are all indicators of a relationship between oral bacteria and increased risk of cardiovascular disease. Another relation between periodontitis and CVD is the increase in serum fibrinogen. Elevated levels of this serum are indicative of CVD. It also increases the risk of hypercoagulability [20].

Conclusion

Understanding the relationship between cardiovascular disease and oral bacteria is difficult because you cannot induce periodontitis or other heart diseases in human subjects. It is also difficult because cardiovascular disease progresses over a lifetime so the studies would have to be over the course of many years. As a result, most of the data demonstrates associations and trends rather than a casual relationship.[31]Studies have been done using animal models. One study examined different immune responses in mice.[27] Looking at the cytokine network, they showed that periodontopathic bacterial lipopolysaccharides (LPS) activate cytokine molecules. P. gingivalis LPS cause a significantly higher activation of cytokine molecules. This demonstrates the relationship between periodontopathic bacteria and the triggering of inflammatory responses.[27][31] The goal of these studies is to ultimately develop a solution. Therapies such as intense dental cleanings and antibiotic treatments have shown benefits in oral health and subsequently improvement in endothelial function. The implications of reduced systemic inflammatory is an improvement of cardiac function.[31] Future studies should continue to examine this relationship as well as focusing on preventative measures.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Eke PI, Dye B, Wei L, Thornton-Evans G, Genco R. Prevalence of Periodontitis in Adults in the United States: 2009 and 2010. J Dent Res. Published online 30 August 2012:1–7.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Kholy, K., Genco, R., & Van Dyke, T. (2015). Oral infections and cardiovascular disease. Trends In Endocrinology &Amp; Metabolism, 26(6), 315-321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tem.2015.03.001

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Underlying Cause of Death, 1999–2018. CDC WONDER Online Database. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2018. Accessed March 12, 2020

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Dietrich, T., Webb, I., Stenhouse, L. et al. Evidence summary: the relationship between oral and cardiovascular disease.Br Dent J 222 , 381–385 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.224

- ↑ Virani SS, Alonso A, Aparicio HJ, Benjamin EJ, Bittencourt MS, Callaway CW, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2021 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2021;143:e254–e743.

- ↑ Mathews, M.J., Mathews, E.H. & Mathews, G.E. Oral health and coronary heart disease. BMC Oral Health 16, 122 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-016-0316-7

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Friedewald, V.E., Kornman, K.S., Beck, J.D., Genco, R., Goldfine, A., Libby, P., Offenbacher, S., Ridker, P.M., Van Dyke, T.E. and Roberts, W.C. (2009), The American Journal of Cardiology and Journal of Periodontology Editors' Consensus: Periodontitis and Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease. Journal of Periodontology,80: 1021-1032. https://doi.org/10.1902/jop.2009.097001

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 Lockhart, P., Bolger, A., Papapanou, P., Osinbowale, O., Trevisan, M., & Levison, M. et al. (2012). Periodontal Disease and Atherosclerotic Vascular Disease: Does the Evidence Support an Independent Association?. Circulation , 125(20), 2520-2544. doi: 10.1161/cir.0b013e31825719f3

- ↑ C-Reactive Protein (CRP) | Labcorp. Labcorp.com. (2022). Retrieved 16 April 2022, from https://www.labcorp.com/help/patient-test-info/c-reactive-protein-crp.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Endothelial Function Testing | Cedars-Sinai. Cedars-sinai.org. (2022). Retrieved 16 April 2022, from https://www.cedars-sinai.org/programs/heart/clinical/womens-heart/conditions/endothelial-function-testing.html#:~:text=The%20endothelium%20is%20a%20thin,substance%20in%20the%20blood)%20adhesion.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Topics, H. (2022). Thrombocytopenia | Platelet Disorders | MedlinePlus. Medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 16 April 2022, from https://medlineplus.gov/plateletdisorders.html#:~:text=Platelets%2C%20also%20known%20as%20thrombocytes,injured%2C%20you%20start%20to%20bleed.

- ↑ Carotid Intima-Media Thickness Test (CIMT) | Cedars-Sinai. Cedars-sinai.org. (2022). Retrieved 16 April 2022, from https://www.cedars-sinai.org/programs/heart/clinical/womens-heart/conditions/cimt-carotid-intima-media-thickness-test.html.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 The Roles and Structure of Teeth|Lion Corporation. Lion.co.jp. (2022). Retrieved 15 April 2022, from https://www.lion.co.jp/en/oral/role/01.htm

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 (What Is Your Cardiovascular System?. Cleveland Clinic. (2022). Retrieved 15 April 2022, from https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/21833-cardiovascular-system.

- ↑ Vasodilation: Your Blood Vessels Opening. Healthline. (2022). Retrieved 16 April 2022, from https://www.healthline.com/health/vasodilation.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Coagulation - Wikipedia. En.wikipedia.org. (2022). Retrieved 16 April 2022, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coagulation.

- ↑ Coronary arteries - Wikipedia. En.wikipedia.org. (2022). Retrieved 16 April 2022, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coronary_arteries.

- ↑ Macleod, M. (2022). PubMed: http://www.pubmed.org. Retrieved 16 April 2022, from https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/carotid-artery-disease

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Wakim, S., & Grewal, M. (2021, September 4). Cardiovascular Disease. Butte College. https://bio.libretexts.org/@go/page/17137

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 20.5 20.6 20.7 Mathews, M.J., Mathews, E.H. & Mathews, G.E. Oral health and coronary heart disease. BMC Oral Health 16, 122 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-016-0316-7

- ↑ Biomarkers. National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. (2022). Retrieved 16 April 2022, from Biomarkers.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Lipoprotein(a): What it is, test results, and what they mean. Medicalnewstoday.com. (2022). Retrieved 16 April 2022, from https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/lipoprotein-a-what-it-is-test-results-and-what-they-mean.

- ↑ Grundy, S. (2002). Low-Density Lipoprotein, Non-High-Density Lipoprotein, and Apolipoprotein B as Targets of Lipid-Lowering Therapy. Circulation, 106(20), 2526-2529. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.0000038419.53000.d6

- ↑ Holland, T. L., Baddour, L. M., Bayer, A. S., Hoen, B., Miro, J. M., & Fowler, V. G., Jr (2016). Infective endocarditis. Nature reviews. Disease primers, 2, 16059. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2016.59

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 Gurarie, M. (2022). What to Know About the Endocardium. Verywell Health. Retrieved 16 April 2022, from https://www.verywellhealth.com/endocardium-definition.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 26.4 26.5 (DARVEAU, R.P., TANNER, A. and PAGE, R.C. (1997), The microbial challenge in periodontitis. Periodontology 2000, 14: 12-32. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0757.1997.tb00190.x

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 27.4 27.5 27.6 27.7 Okuda, K., Kato, T. and Ishihara, K. (2004), Involvement of periodontopathic biofilm in vascular diseases. Oral Diseases, 10: 5-12. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1354-523X.2003.00979.x

- ↑ Pathogenic bacteria - Wikipedia. En.wikipedia.org. (2022). Retrieved 16 April 2022, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pathogenic_bacteria.

- ↑ Leukocytes. Physiopedia. (2022). Retrieved 16 April 2022, from https://www.physio-pedia.com/Leukocytes.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Folwaczny, M., Bauer, F., & Grünberg, C. (2019). Significance of oral health in adult patients with congenital heart disease. Cardiovascular diagnosis and therapy, 9(Suppl 2), S377–S387. https://doi.org/10.21037/cdt.2018.09.17)

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 Tonetti, M., D'Aiuto, F., Nibali, L., Donald, A., Storry, C., & Parkar, M. et al. (2007). Treatment of Periodontitis and Endothelial Function. New England Journal Of Medicine, 356(9), 911-920. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa063186

- ↑ Insulin and Glucagon: How Do They Work?. Healthline. (2022). Retrieved 16 April 2022, from https://www.healthline.com/health/diabetes/insulin-and-glucagon.

- ↑ Kawasaki, H., Kuroda, S., & Mimaki, Y. (2000). Nihon yakurigaku zasshi. Folia pharmacologica Japonica, 115(5), 287–294. https://doi.org/10.1254/fpj.115.287

- ↑ UI researchers study abnormal blood clotting in diabetes | Carver College of Medicine. Medicine.uiowa.edu. (2022). Retrieved 16 April 2022, from https://medicine.uiowa.edu/content/ui-researchers-study-abnormal-blood-clotting-diabetes.

Authored for BIOL 238 Microbiology, taught by Joan Slonczewski, 2022, Kenyon College