Microorganism Bacillus licheniformis: Difference between revisions

| Line 33: | Line 33: | ||

==Description and Significance== | ==Description and Significance== | ||

[[Image:Colony_Morphology.jpeg|thumb|''Licheniform growth on agar plate'']] | [[Image:Colony_Morphology.jpeg|thumb|''Licheniform growth on agar plate'']] | ||

Latest revision as of 17:43, 4 December 2015

Classification

Domain: Bacteria Phylum: Firmicutes Class: Bacilli Order: Bacillales Family: Bacillaceae Genus: Bacillus

Species

|

NCBI: Taxonomy |

Bacillus licheniformis

Habitat Information

Bacillus licheniformis is a nonpathogenic soil organism. Because it is capable of forming endospores that can be easily disseminated, B. licheniformis can be isolated from a variety of places, though it is mainly associated with plant materials. It is also often found on feathers of ground-dwelling and aquatic species of birds.

Description and Significance

B. licheniformis is a rod-shaped, gram positive motile bacterium. It is spore-forming under harsh conditions and closely related to the widely studied B. subtilis. Unlike other bacilli which are predominately aerobic, B. licheniformis is a facultative anaerobe, which explains it's ability to grow in additional ecological niches and environments.

Colonies are both round and irregular in shape, with irregular (undulate, fimbriate) margins. The surface of B. licheniformis colonies are often rough and wrinkled, with "licheniform", or hair-like growths. Color ranges from opaque to white.

B. licheniformis exhibits antimicrobial activity against both Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus. It is also resistant to some commonly used antibiotics, including oxacillin and nafcillin. It is also used to produce bacitracin, a peptide topical and intramuscular antibiotic.

Genome Structure

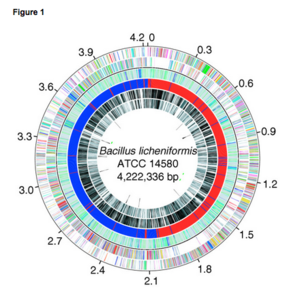

The complete nucleotide sequence of B. licheniformis is ATCC 14580 genome which forms a circular chromosome of 4,222,336 base-pairs (bp) containing 4,208 predicted protein-coding genes with size averaging at 873 bp, 7 rRNA operons, and 72 tRNA genes. The B. licheniformis chromosome contains large regions that are colinear with the genomes of B. subtilis and Bacillus halodurans, and approximately 80% of the predicted B. licheniformis coding sequences have B. subtilis orthologs [1].

Ribosomal sequence obtained from PCR:

ANACGGAGCAACGCCGCGTGAGTGATGAAGGTTTTCGGATCGTAAAACTCTGTTGTTAGGGAAGAACAAGTACCGTTCGAATAGGGCGGTACCTTGACGGTACCTAACCAGAAAGCCACGGCTAACTACGTGCCAGCAGCCGCGGTAATACGTAGGTGGCAAGCGTTGTCCGGAATTATTGGGCGTAAAGCGCGCGCAGGCGGTTTCTTAAGTCTGATGTGAAAGCCCCCGGCTCAACCGGGGAGGGTCATTGGAAACTGGGGAACTTGAGTGCAGAAGAGGAGAGTGGAATTCCACGTGTAGCGGTGAAATGCGTAGAGATGTGGAGGAACACCAGTGGCGAAGGCGACTCTCTGGTCTGTAACTGACGCTGAGGCGCGAAAGCGTGGGGAGCGAACAGGATTAGATACCCTGGTAGTCCACGCCGTAAACGATGAGTGCTAAGTGTTAGAGGGTTTCCGCCCTTTAGTGCTGCAGCAAACGCATTAAGCACTCCGCCTGGGGAGTACGGTCGCAAGACTGAAACTCAAAGGAATTGACGGGGGCCCGCACAAGCGGTGGAGCATGTGGTTTAATTCGAAGCAACGCGAAGAACCTTACCAGGTCTTGACATCCTCTGACAACCCTAGAGATAGGGCTTCCCCTTCGGGGGCAGAGTGACAGGTGGTGCATGGTTGTCGTCAGCTCGTGTCGTGAGATGTCATAGNCTGTTTTNCNGNC

Cell Structure, Metabolism and Life Cycle

The cell wall of Bacillus licheniformis is composed of mucopeptide, which is made up of linear chains of alternating amino sugars and short peptide chains of 3-5 amino acids. Cross-links between peptide chains create a crystal-lattice like structure [6].

Optimal growth of B. licheniformis occurs around 50°C, but the organism can survive at much higher/lower temperatures for extended periods because it is spore-forming. Endospores allow the organism to survive in a variety of harsh environments (high salt concentrations, for example) until conditions are more favorable, when it returns to a vegetative state. Optimal temperature for enzyme secretion is at human body temperature, 37°C. B. licheniformis produces many extracellular enzymes, including proteases and lipases which aid in digestion of proteins and fats, respectively. It is also a facultative anaerobe.

Physiology and Pathogenesis

B. licheniformis is closely related to Bacillus subtilis.

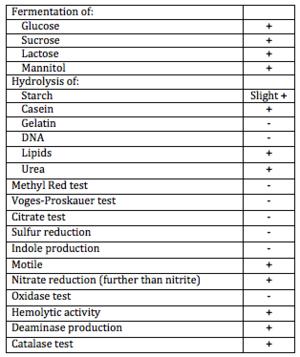

B. licheniformis is a motile organism capable of fermenting sugars (lactose, glucose, mannitol) and excreting useful extracellular enzymes including but not limited to: catalase, casease, urease, deaminase, protease, and lipase. It also exhibits some hemolytic activity and is salt tolerant.

B. licheniformis lives in the barbules, or terminal branches of the barbs of a bird feather. The organism secretes a keratinase which is capable of complete degradation of a feather within 24 hours, as feathers are made up of 90% keratin.

Some toxins produced by B. licheniformis have been shown to cause food poisoning in humans. Outbreaks are predominately associated with cooked meats, vegetables, milk products, and baby food. Because B. licheniformis is spore-forming, it it likely to survive industrial processing, i.e. milk pasteurization. Although B. licheniformis often occurs in high numbers in these foods, it's presence is not usually regulated in contrast to B. cereus, which is credited with most food poisoning incidents by the Bacillus species. Food poisoning can cause cramping, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, and fatalities by B. licheniformis toxins, though rare, have been reported.

Applications

Manufacture of Enzymes, Chemicals, Antibiotics

The ability of B. licheniformis to form endospores allows it to survive in the harsh environments required to manufacture industrial enzymes, chemicals, and antibiotics. Proteases are often included in detergents, and amylases in the desizing of textiles and sizing of papers. Specific strains are also used to produce peptide antibiotics like bacitracin and proticin, as well as some specialty chemicals, including citric acid, inosine, inosinic acid, and poly-γ-glutamic acid [1].

Animal Feed Industry

Feathers are a major by-product of the poultry processing industry that are particularly difficult to degrade. Keratinolytic activities of B. licheniformis could aid in converting this by-product into a useful protein source for animal feed. The ability to turn waste feathers into feed would reduce feed costs and decrease the need for pollutants currently used to degrade these feathers [3].

Dental

Scientists at Newcastle University have been researching how the organism's ability to release an enzyme that breaks down external DNA may aid in breakdown of dental biofilms, or plaque. Lab tests have confirmed the enzyme's ability to break up and remove bacteria present in plaque, and thus prevent the build up of plaque. Addition of this enzyme to toothpastes, mouthwash, etc. could help reduce the prevalence of dental caries. [5]

References

(5) Wilkinson, T. (4 July 4 2012). "Seaweed could fight tooth decay – scientists". Independent.ie.

Author

Page authored by Clarissa Alejandro and Erin Collins, students of Prof. Kristine Hollingsworth at Austin Community College.