Pseudomonas syringae: Bioprecipitation Mechanisms and Implications: Difference between revisions

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

[[Image:Project Pic.jpg|thumb|800px|left|Fig.2 The bioprecipitation cycle diagram with two key factors that highlight the system. First, micro-organisms such as <i>P.syringae</i> that conduct the ice nucleation process. Second, the water vapor from plants, oceans, and aquatic environments that these micro-organism use in the atmosphere. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/gcb.12447/epdf.]] | [[Image:Project Pic.jpg|thumb|800px|left|Fig.2 The bioprecipitation cycle diagram with two key factors that highlight the system. First, micro-organisms such as <i>P.syringae</i> that conduct the ice nucleation process. Second, the water vapor from plants, oceans, and aquatic environments that these micro-organism use in the atmosphere. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/gcb.12447/epdf.]] | ||

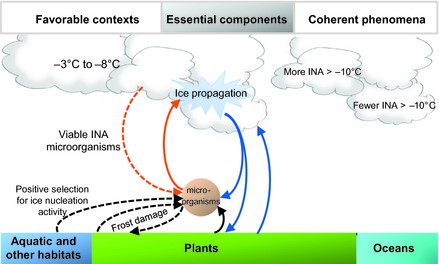

Bioprecipitation is a term used to describe the concept in which precipitation is caused by bacteria. This is important because organisms such as bacteria that can drive our precipitation patterns, due to cloud formation, of any given area can be vital in predicting weather patterns. Also it deepen our understanding of the water cycle and how the water cycle effects ecosystems based on the makeup of the microbial community. Bioprecipitation has a strong correlation with <i>P.syringae</i>. <i>P.syringae</i> is thought to have two significant roles in cloud formation that effect bioprecipitation (Morris et al. 2013) | Bioprecipitation is a term used to describe the concept in which precipitation is caused by bacteria. This is important because organisms such as bacteria that can drive our precipitation patterns, due to cloud formation, of any given area can be vital in predicting weather patterns. Also it deepen our understanding of the water cycle and how the water cycle effects ecosystems based on the makeup of the microbial community. Bioprecipitation has a strong correlation with <i>P.syringae</i>. <i>P.syringae</i> is thought to have two significant roles in cloud formation that effect bioprecipitation (Morris et al. 2013)[[#References|[9]]]. One role is that due to its warm temperature ice nucleation activity, temperatures range from subzero to eight degrees Celsius. <i>P.syringae</i> is an organism that can cause water vapor droplets to freeze at temperatures and conditions that normal abundant mineral ice nucleator particles are unsuccessful at achieving. The second role that this bacteria causes water vapor to freeze to a large enough size for gravity to act on the droplets in clouds which causes precipitation such as snow or rain. This is important because much of rainfall that comes from mid-high altitudes are as result of this water droplet freezing process (Morris et al. 2013)[[#References|[9]]]. This process either occurs by nucleation minerals present in clouds or microbial life such as <i>P.synrigae</i> that are also present in clouds. As described by in recent studies, <i>P.syringae</i> bioprecipitiation is constructed within the water cycle (Christner 2012)[[#References|[2]]]. It was first discovered by a man named David Sands in the 1970s. Sands found the same pseudomonas bacteria that caused frost damage was also found in the rainfall of that area (Prasanth 2015)[[#References|[15]]]. The bioprecipitation process can be compartmentalized and explained in a few steps within the water cycle (Figure 2). The first step is for ice nucleators such as <i>P.syringae</i> to become airborne in atmosphere ready to act on water vapor and ice nuclei at very low temperatures. The second step is for ice nucleation to occur using proteins that <i>P.syringae</i> possesses to facilitate this process. At this step cloud formation occurs and condensation of water vapor and ice nuclei takes place. The third step is traditional for the water cycle: the cloud becomes too heavy and gravity pulls the snow, rain, or any other form of precipitation from the cloud down to the Earth’s surface. This cycle continues which could potentially have a major impact on cloud formation and climate patterns. However, it has been found that <i>P.syringae</i> only accounts for only a small fraction of the total microbial life deposited by rainfall (Christner 2012)[[#References|[2]]]. This makes it difficult to make the claim that bioprecipitation caused by <i>P.syringae</i> influences ecosystems on a global scale. However, research has suggested that <i>P.syringae</i> and other similar bacteria lose their ability to be cultured but continue their high ice nucleation activity (Christner 2012)[[#References|[2]]]. This leaves more opportunity to explore how the rate of ice nucleation via <i>P.syringae</i> effects bioprecipitation despite their low atmospheric population discovered through precipitation samples. Also, the potential potency of <i>P.syringae</i> increases because they are able to grow in a wide range of environments (Morris et al. 2014)[[#References|[12]]]. This bacteria’s life cycle can be conducted in air-borne environments, as well as soil and non-air-borne environments. Other microbial species’ life cycle are heavily dependent on air-borne distribution and deposition through rainfall. These species have recently been shown to be high in ice nucleation activity as well (Morris et al. 2014)[[#References|[12]]]. This is noteworthy because more microbes other than <i>P.syringae</i> may have a high impact on bioprecipitation. This could also potentially explain the low population numbers of <i>P.syringae</i> in precipitation samples. A deeper understanding of <i>P.syringae’s</i> protein structure and function regarding ice nucleation is important to expanding knowledge on bioprecipitation as a whole. | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

Revision as of 00:51, 29 April 2016

Overview

By Brandon Byrd

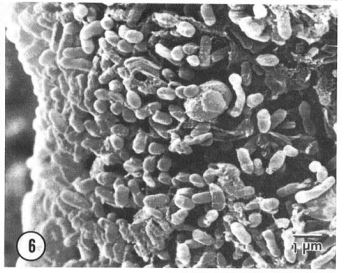

Pseudomonas syringae have a significant impact on weather systems and ecosystems worldwide. This bacteria has previously been studied in depth as a plant pathogen, and it has recently been studied as a major contributor to bioprecipitation. P.syringae are rod shaped, gram-negative bacteria with polar flagella that is a plant pathogen to a wide variety of plant species at cold temperatures (Morris et al. 2008)[10]. This bacteria is found in agricultural locations as well as non-agricultural locations such as clouds (Morris et al. 2008)[10]. The fact that it has the capability to grow in a wide range of environments and ecosystems gives this bacteria the potential to drastically impact biogeographical systems. P.syringae also has an extraordinary ice nucleation activity which allows this bacteria to catalyze freezing water at warm temperatures which sparked interest in its role in the water cycle (Maki et al. 1974)[8]. This is a major key for P.syringae’s effect on biogeographical systems. It is also important to further analyze their ice nucleation ability to understand the mechanisms in which they influence major weather systems such as the water cycle. Furthermore, how P.syringae can impact humans and biodiversity based on their influence on ecosystems and the environment.

History

.

P.syringae are a part of the pseudomonas genus (Figure 1). This genus is gram-negative aerobic proteobacteria. This genus is categorized as pathogens with a wide variety of niche potential due to much variation in metabolism across the species in this genus (Morris et al. 2013)[9]. The history of the pseudomonas genus dates back millions of years ago to when they were found in aquatic habitats before plants and land agriculture (Morris et al. 2013)[9]. Pseudomonas is still one of the most common bacteria present in many aquatic environments today such as oceans and wetlands. Also, a study done by Pesciaroli[14] and colleagues have shown a new strain of P.syringae to be present in intertidal aquatic environments (Morris et al. 2013)[9]. P.syringae was first discovered by Paul Hoppe in 1961 while studying corn crops for the U.S. Department of Agriculture (Parrott 1993)[13]. His study demonstrated a bacteria that caused crop freezing problems at temperatures around negative two to four degrees Celsius. His research led to further research in later years which revealed P.syringae and its ice nucleation characteristics which were causing the crop freezing problems. The crop freezing problem that occurred is that between negative eight to four degrees plant stems and roots would freeze due to the presence of P.syringae. Ice nucleation research of P.syringae has led to a cascade of promising discoveries linking this species to important bioprecipitation mechanisms that continue to influence weather in many ecosystems. There was a discovery of ice nucleation proteins that protrude from the outer membrane of P.syringae which facilitates their ice nucleation ability (Morris et al. 2013)[9]. These proteins are believed to have arisen without the use of horizontal gene transfer millions of years ago because of evidence of a three secretion system (Morris et al. 2010)[11]. The gene for the outer membrane ice nucleation protein is most likely in the core genome of proteobacteria such as Pseudomonas syringae. The most likely common ancestor of this gene came from more general orders including Pseudomonadales and also Enterobacteriales (Morris et al. 2013)[9]. The study of these ice nucleation proteins have given rise to the present research regarding P.syringae in its direct significance to the water cycle and indirect significance to other biogeographical systems.

Bioprecipitation and P.syringae’s Role in Bioprecipitation

Bioprecipitation is a term used to describe the concept in which precipitation is caused by bacteria. This is important because organisms such as bacteria that can drive our precipitation patterns, due to cloud formation, of any given area can be vital in predicting weather patterns. Also it deepen our understanding of the water cycle and how the water cycle effects ecosystems based on the makeup of the microbial community. Bioprecipitation has a strong correlation with P.syringae. P.syringae is thought to have two significant roles in cloud formation that effect bioprecipitation (Morris et al. 2013)[9]. One role is that due to its warm temperature ice nucleation activity, temperatures range from subzero to eight degrees Celsius. P.syringae is an organism that can cause water vapor droplets to freeze at temperatures and conditions that normal abundant mineral ice nucleator particles are unsuccessful at achieving. The second role that this bacteria causes water vapor to freeze to a large enough size for gravity to act on the droplets in clouds which causes precipitation such as snow or rain. This is important because much of rainfall that comes from mid-high altitudes are as result of this water droplet freezing process (Morris et al. 2013)[9]. This process either occurs by nucleation minerals present in clouds or microbial life such as P.synrigae that are also present in clouds. As described by in recent studies, P.syringae bioprecipitiation is constructed within the water cycle (Christner 2012)[2]. It was first discovered by a man named David Sands in the 1970s. Sands found the same pseudomonas bacteria that caused frost damage was also found in the rainfall of that area (Prasanth 2015)[15]. The bioprecipitation process can be compartmentalized and explained in a few steps within the water cycle (Figure 2). The first step is for ice nucleators such as P.syringae to become airborne in atmosphere ready to act on water vapor and ice nuclei at very low temperatures. The second step is for ice nucleation to occur using proteins that P.syringae possesses to facilitate this process. At this step cloud formation occurs and condensation of water vapor and ice nuclei takes place. The third step is traditional for the water cycle: the cloud becomes too heavy and gravity pulls the snow, rain, or any other form of precipitation from the cloud down to the Earth’s surface. This cycle continues which could potentially have a major impact on cloud formation and climate patterns. However, it has been found that P.syringae only accounts for only a small fraction of the total microbial life deposited by rainfall (Christner 2012)[2]. This makes it difficult to make the claim that bioprecipitation caused by P.syringae influences ecosystems on a global scale. However, research has suggested that P.syringae and other similar bacteria lose their ability to be cultured but continue their high ice nucleation activity (Christner 2012)[2]. This leaves more opportunity to explore how the rate of ice nucleation via P.syringae effects bioprecipitation despite their low atmospheric population discovered through precipitation samples. Also, the potential potency of P.syringae increases because they are able to grow in a wide range of environments (Morris et al. 2014)[12]. This bacteria’s life cycle can be conducted in air-borne environments, as well as soil and non-air-borne environments. Other microbial species’ life cycle are heavily dependent on air-borne distribution and deposition through rainfall. These species have recently been shown to be high in ice nucleation activity as well (Morris et al. 2014)[12]. This is noteworthy because more microbes other than P.syringae may have a high impact on bioprecipitation. This could also potentially explain the low population numbers of P.syringae in precipitation samples. A deeper understanding of P.syringae’s protein structure and function regarding ice nucleation is important to expanding knowledge on bioprecipitation as a whole.

Mechanisms for Ice Nucleation

P.syringae ice nucleation is due to the proteins within its outer membrane of the bacteria. This protein is known as the lnaZ protein. The structure of InaZ has been studied in depth as well. Model simulations have proposed the structure of ice nucleation proteins such as InaZ to have on side for the purpose of organizing water molecules into an ice structure, and the other side of the protein for binding to the cell membrane of the bacteria (Kajava and Lindow 1993)[1]. More recent studies have shown that there are significant greater amounts of beta-sheets than alpha-helices in quaternary protein structure (Graether and Jia 2001)[2]. The significance of this is not known, but these results produce an intriguing area of research since increasing our knowledgebase of the InaZ protein structure influencing its function will aid in understanding the mechanisms of InaZ proteins.

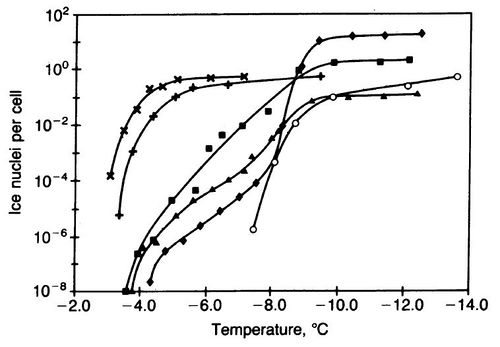

Studies have proven that the lnaZ protein is coded by the p153 gene in P.syringae (Wolber et al. 1986)[3]

. P.syringae with functioning InaZ proteins have a genotype of InaZ+ whereas P.syringae without functioning InaZ have a genotype of InaZ-. Most InaZ- P.syringae are mutates in comparative studies regarding InaZ protein function in an experiment (Figure 3). The main function of the InaZ protein is to participate in ice crystallization of pure water. Other studies have shown that there is no evidence that the ice nucleation protein serves any function other than ice nucleation; therefore, the positive natural selection of the InaZ protein is based on the ability of an organism to ice nucleate (Morris et al. 2014)[4]. There are two types of crystallization: homogeneous and heterogeneous. Homogeneous crystallization occurs when the right conditions-negative eight to four degree temperature range, water vapor, atmospheric pressure- are reached for the formation of ice due to a group of water molecules to orientate their particles into a certain order (Wolber et al. 1986)[5]

. This type of crystallization is also known as ice nuclei crystallization. Heterogeneous crystallization is when solid, non-water molecules, are used for ice formation sites (Wolber et al. 1986)[6]

. P.syringae InaZ proteins conduct homogenous or ice nuclei crystallization. The efficiency of the ice crystallization depends on the environmental conditions and cell concentration. Wolber and colleagues also found a common repeating Alanine-Glycine-Tyrosine-Glycine-Serine-Threonine-Leucine pattern within a 1200 amino acid sequence in the InaZ protein complex. This sequence is considered to be responsible for water molecule organization due to alterations in spatial location and alignment prompting ice formation (Cid et al. 2016)[7]. The most favorable environment for optimal P.syringae is a high water vapor environment, although there has been a water vapor threshold or capacity where efficiency becomes independent of the concentration (Wolber et al. 1986)[8]. However, InaZ have been shown to be more efficient than other ice nucleators such as other fungi species and ash, dust, soot, and other ice nucleation minerals (Morris et al. 2014)[9]. One proposed reason for this is that P.syringae InaZ proteins have more amounts of ice active sites per surface area of their cells in fungi InaZ proteins. The mechanisms of InaZ gene to protein pathways and InaZ protein function are still being investigated in the present day.

Ecological Implications of

P.syringae Bioprecipitation

P.syringae is a fairly abundant bacteria in nature. P. syringae has been found in a wide range of environments that have favorable substrates to the water cycle. These include plant canopies, clouds, snow and rainfall, leaf litter, lakes, oceans, rivers, and biofilms associated with wild and cultured plants (Morris et al. 2013)[10]. This is significant since these locations are high in water and water vapor content. Therefore, P.syringae is very important for recycling water in many different ecosystems due to its ice nucleation abilities. It has the potential to change the amount of precipitation in a given ecosystem which can possibly limit plant diversity based on water level tolerances of a given plant species. Also, if there are less P.syringae in the atmosphere then the amount of water vapor increases since the vapor is not being condensed and frozen into potential precipitation from clouds. Both of these factors can control the diversity of ecosystems that depend on P.syringae to drive a significant part of their regional water cycle. This diversity dynamic not only effects plant species but also other animal species at higher trophic levels that depend on these plants for energy. Less plant diversity could lead to less available energy in a given system if other plant species are not able to fill previous plants’ ecological niches. This is logical reasoning because the science community knows that plants are the primary producers in a trophic web ecosystem. Therefore, reduction or addition of more plants into an ecosystem can alter the amount of available energy in a system, which causes a cascade of effects.

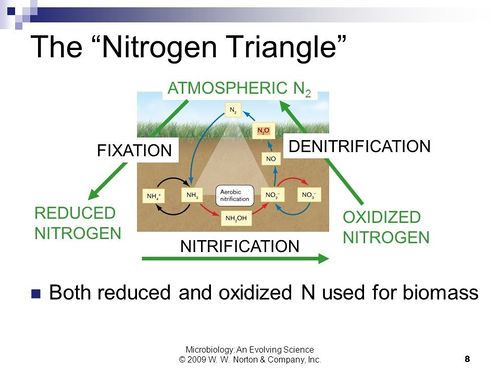

Ecologcial effects caused by P.syringae’s impact on the water cycle may bleed into other important natural cycles and biodiversity. For example, if there is more precipitation in a heavily agricultural based area such as a farm, this can lead to more nitrogen runoff into water systems such as nearby rivers and lakes. Therefore, the population numbers of an ice nucleating organism like P.syringae can have a profound effect on the nitrogen cycle. The nitrogen cycle can be broken into three sections of the organization model known as the nitrogen triangle (Figure 4). High populations can accelerate the nitrification phase of the cycle in the nitrogen triangle and decelerate denitrification of oxidized compounds returning to atmospheric form. This happens because the higher populations of P.syringae in the atmosphere could lead to precipitation increases due to their ice nucleation ability via the InaZ protein (Morris et al. 2013)[11]. Consequently, increasing in the amount of nitrogen runoff into local water systems from farm fertilizers and thereby causing reactive nitrogen levels in these water systems to increase. This not only effects the nitrogen cycle, but it also affects the organisms that live in these lakes and streams.

Nitrogen level effects on marine has been studied in detail throughout the science community. In the aquatic ecosystem, reactive deposition into primarily fresh water ecosystems can increase the acidity of the water (Erisman et al. 2013)[12]. Constant acidification of the water systems can cause the ecosystem to favor acid tolerant organisms such as phytoplankton. This changes the food chain dynamic of the ecosystem because many fish and invertebrates in aquatic ecosystems are sensitive to acidification. Thus, resulting in a decrease in their population levels (Erisman et al. 2013)[13] Acidification also has also been shown to effect organisms at higher trophic levels such as birds, zooplankton, amphibians, and benthic invertebrates directly and indirectly (Erisman et al. 2013)[14]. Eutrophication can be a result of higher nitrogen levels into marine ecosystems via fertilizer runoff. Local water systems such as lakes are typically low in nitrogen nutrients. However, the introduction of nitrogen to the water system can cause the nutrients to increase. Organisms like phytoplankton that are more effective in assimilating these nutrients are better suited for these conditions over species limited by other factors (Erisman et al. 2013)[15]. For example, diatoms’ limiting factor is silica and benthic plants are limited by light availability. The higher nutrients in the water can cause algal blooms by cyanobacteria which can cover the surface water of lakes. This can then lead to hypoxia at the surface when deadly toxins are released creating dead zones (Erisman et al. 2013)[16]. This again can change the effect on higher trophic organisms such as fish and invertebrates. Furthermore, in ecosystems with minimal water turnover- lakes for example- the sedimentation and breakdown of the organic biomass from algal blooms in the water causes oxygen depletion in the water (Erisman et al. 2013)[17]. This further changes biodiversity in the ecosystem to favor more oxygen tolerant species which are low in population number. Constant changes to the biodiversity can alter nutrient cycling in the aquatic ecosystem which changes the ecosystem as a whole (Erisman et al. 2013)[18]. These ecological alterations can be looped back to the presence of P.syringae levels in a given area. Since these changes stem from agricultural runoff which is controlled by precipitation level, P.syringae is important because it is one of the regulators of precipitation and cloud formation.

Changes in land use could also influence the bioprecipitation cycle causing climate fluctuations and changes to ice nucleating organisms like P.syringaes’ future role in this cycle. Modifications to the vegetation density and type have been shown to change the source of ice nucleating organisms released into the atmosphere, therefore impacting cloud formation, cloud patterns, and precipitation patterns (Morris et al. 2014)[19]. This results in fluctuations in the amount of radiation entering the upper atmosphere and hitting the Earth’s surface. This causes possible effects on the regional climate. A change in regional climate can affect agricultural methods for farmers since crops grow more productively at particular temperatures. Thus, impacting what kinds of crops can be grown in different regions and ultimately effecting the yield farms collect per growing season. Change in regional climate can also change the diversity of life within the regions ecosystem for similar reasoning. Organisms are known to be affected by climate change. This is because organisms such as macroinvertbrates have thermal neutral zones (Burgmer et al. 2007)[20]. Thermal neutral zones are the tolerance ranges of a specific species of organisms. Therefore, fluctuations and changes in climate can alter the biodiversity in a given region since climate changes may force some species to operate outside their climate tolerance. When this occurs these species may die off, therefore reducing the biodiversity in the region. However, climate change may increase the populations of endemic species or provide ecological opportunity for new species. This is because the change organisms that optimally operate at the new temperatures, due to the climate change, will thrive and reproduce. The net effect of the climate change will then be a reduction, if new species do not replace endemic species, or a change in biodiversity, if new species do replace endemic species. These phenomena demonstrate P.syringaes’ importance to agricultural methods and biodiversity on a regional scale.

Conclusion

P.syringae are an important part of Earth’s weather system and ecosystem structure. This is because P.syringae’s significant role in bioprecipitation and the water cycle. The mechanisms of their ice nucleation and cloud seeding has been proven to be a result of their IanZ protein. The IanZ protein is the driving force in P.syringae’s ice nucleation abilities. The effects P.syringae has on bioprecipation carries over to effects on the nitrogen cycle and climate change. This implications can alter the landscape of a region, thereby further impacting biodiversity in ecosystems and agricultural methods for farmers. P.syringae are an important part of the microbial community that impacts abiotic and biotic ecosystem factors in various ways.

References

- ↑ Kajava, A.V. and Lindow, S. E. 1993. A model for three-dimensional structure of ice nucleation proteins. J. Mol. Biol. Vol 232: 709-717.

- ↑ Graether, S.P. and Jia, Z. 2001. Modeling pseudomonas syringae ice-nucleation protein as a -helical protein. Biophysical Journal. Vol 80: 1169-1173.

- ↑ Wolber, P.K. et al. 1986. Identification and purification of a bacterial ice-nucleation protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. Vol. 83, pp. 7256-7260.

- ↑ Morris, C.E. et al. “Bioprecipitation: a feedback cycle linking earth history, ecosystem dynamics and land use through biological ice nucleators in the atmosphere.” 2014. Global Change Biology 20: 341–351.

- ↑ Wolber, P.K. et al. 1986. Identification and purification of a bacterial ice-nucleation protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. Vol. 83, pp. 7256-7260.

- ↑ Wolber, P.K. et al. 1986. Identification and purification of a bacterial ice-nucleation protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. Vol. 83, pp. 7256-7260.

- ↑ Cid, F.P. et al. 2016. Properties and biotechnological applications of ice binding proteins in bacteria. FEMS Microbiology Letters.

- ↑ Wolber, P.K. et al. 1986. Identification and purification of a bacterial ice-nucleation protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. Vol. 83, pp. 7256-7260.

- ↑ Morris, C.E. et al. “Bioprecipitation: a feedback cycle linking earth history, ecosystem dynamics and land use through biological ice nucleators in the atmosphere.” 2014. Global Change Biology 20: 341–351.

- ↑ Morris, C. E. et al. The life history of Pseudomonas syringae: linking agriculture to earth system processes. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2013. Vol. 51: 85–104

- ↑ Morris, C. E. et al. The life history of Pseudomonas syringae: linking agriculture to earth system processes. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2013. Vol. 51: 85–104

- ↑ Erisman, J.W. 2013. Consequences of human modification of the global nitrogen cycle. Phil Trans R Soc. B 368: 20130116.

- ↑ Erisman, J.W. 2013. Consequences of human modification of the global nitrogen cycle. Phil Trans R Soc. B 368: 20130116.

- ↑ Erisman, J.W. 2013. Consequences of human modification of the global nitrogen cycle. Phil Trans R Soc. B 368: 20130116.

- ↑ Erisman, J.W. 2013. Consequences of human modification of the global nitrogen cycle. Phil Trans R Soc. B 368: 20130116.

- ↑ Erisman, J.W. 2013. Consequences of human modification of the global nitrogen cycle. Phil Trans R Soc. B 368: 20130116.

- ↑ Erisman, J.W. 2013. Consequences of human modification of the global nitrogen cycle. Phil Trans R Soc. B 368: 20130116.

- ↑ Erisman, J.W. 2013. Consequences of human modification of the global nitrogen cycle. Phil Trans R Soc. B 368: 20130116.

- ↑ Morris et al. 2014. Bioprecipitation: a feedback cycle linking Earth history, ecosystem dynamics and land use through biological ice nucleators in the atmosphere. Global Change Biology Vol. 20: 341–351

- ↑ Burgmer, T. et al. 2007. Effects of climate-driven temperature changes on the diversity of freshwater macroinvertebrates. Oecologia Vol. 151: 93-103.

Authored for BIOL 238 Microbiology, taught by Joan Slonczewski, 2016, Kenyon College.

1.Burgmer, T. et al. 2007. Effects of climate-driven temperature changes on the diversity of freshwater macroinvertebrates. Oecologia Vol. 151: 93-103.

http://download.springer.com/static/pdf/405/art%253A10.1007%252Fs00442-006-0542-9.pdf?originUrl=http%3A%2F%2Flink.springer.com%2Farticle%2F10.1007%2Fs00442-006-0542-9&token2=exp=1461612065~acl=%2Fstatic%2Fpdf%2F405%2Fart%25253A10.1007%25252Fs00442-006-0542-9.pdf%3ForiginUrl%3Dhttp%253A%252F%252Flink.springer.com%252Farticle%252F10.1007%252Fs00442-006-0542-9*~hmac=1d0eca244036a3758432a3ddd64c9a7bd8d9da38d61bc77ae9a6a025422223a7

2.Christner, Brent C. "Cloudy With a Chance of Microbes." Microbe 7.2 (2012): 70-75. Christner Research Group. Louisiana State University. Web. 28 Oct. 2012.

http://brent.xner.net/pdf/Christner2012_CloudyMicrobes.pdf

3.Cid, F.P. et al. 2016. Properties and biotechnological applications of ice binding proteins in bacteria. FEMS Microbiology Letters. http://femsle.oxfordjournals.org/content/femsle/early/2016/04/15/femsle.fnw099.full.pdf

4.Erisman, J.W. 2013. Consequences of human modification of the global nitrogen cycle. Phil Trans R Soc. B 368: 20130116. http://rstb.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/royptb/368/1621/20130116.full.pdf 5. Getz, S. et al. 1983. Scanning electron microscopy of infection sites and lesion development on tomato fruit infected with pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato. Cytology and Histology Vol. 1. No. 1: 39-43. http://www.apsnet.org/publications/phytopathology/backissues/Documents/1983Articles/Phyto73n01_39.PDF

6.Graether, S.P. and Jia, Z. 2001. Modeling pseudomonas syringae ice-nucleation protein as a -helical protein. Biophysical Journal. Vol 80: 1169-1173. http://ac.els-cdn.com/S0006349501760936/1-s2.0-S0006349501760936-main.pdf?_tid=19bf5122-0837-11e6-8f07-00000aacb35d&acdnat=1461294523_f0821815d32d5e89b548f49000de9d2c

7.Kajava, A.V. and Lindow, S. E. 1993. A model for three-dimensional structure of ice nucleation proteins. J. Mol. Biol. Vol 232: 709-717. http://ac.els-cdn.com/S0022283683714245/1-s2.0-S0022283683714245-main.pdf?_tid=df0ee12a-0834-11e6-9433-00000aacb35f&acdnat=1461293565_d8dd31a5da5445e945bf0c2effb17201

8.Maki et al. 1974. Ice Nucleation induced by Pseudomonas syringae. American Society for Microbiology Vol. 28, No. 3: 456-459. http://aem.asm.org/content/28/3/456.full.pdf+html

9.Morris, C. E. et al. 2013. The life history of Pseudomonas syringae: linking agriculture to earth system processes. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. Vol. 51: 85–104 http://www.annualreviews.org/doi/pdf/10.1146/annurev-phyto-082712-102402

10.Morris et al. 2008. The life history of the plant pathogen Pseudomonas syringae is linked to the water cycle. The ISME Journal Vol. 2: 321–334 http://www.nature.com/ismej/journal/v2/n3/full/ismej2007113a.html

11.Morris C.E., Sands D.C., Vanneste J.L., Montarry J, Oakley B, et al. 2010. Inferring the evolutionary history of the plant pathogen Pseudomonas syringae from its biogeography in headwaters of rivers in North America, Europe and New Zealand. mBio 1(3):e00107-10 http://mbio.asm.org/content/1/3/e00107-10.full.pdf+html

12.Morris et al. 2014. Bioprecipitation: a feedback cycle linking Earth history, ecosystem dynamics and land use through biological ice nucleators in the atmosphere. Global Change Biology Vol. 20: 341–351 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/gcb.12447/epdf

13.Parrott, Carolyn C. 1993. Recombinant DNA to Protect Crops. Woodrow Wilson Biology Institute. https://web.archive.org/web/20120918071426/http://www.woodrow.org/teachers/bi/1993/recombinant.html

14.Pesciaroli C, Cupini F, Selbmann L, Barghini P, Fenice M. 2012. Temperature preferences of bacteria isolated from seawater collected in Kandalaksha Bay,White Sea, Russia. Polar Biol. 35:435–45

http://wsbs-msu.ru/res/DictionaryAttachment/602/DOC_FILENAME/C%20Pesciaroli%20et%20al%202012%20Termperature%20preferences%20of%20bacteria%20isolated%20from%20seawater%20collected%20in%20Kandaklaksha%20Bay.pdf

15.Prasanthm M, et al. 2015. Pseudomonas syringae: An overview and its future as a “rain making bacteria”. International Research Journal of Biological Sciences Vol. 4(2): 70-77.

http://www.isca.in/IJBS/Archive/v4/i2/13.ISCA-IRJBS-2014-229.pdf

16.Slonczewski, Joan L., and John Watkins. Foster. Microbiology: An Evolving Science. First ed. New York: W.W. Norton Et, 2009. Print http://slideplayer.com/slide/7448073/ 17. Wolber, P.K. et al. 1986. Identification and purification of a bacterial ice-nucleation protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. Vol. 83, pp. 7256-7260. http://www.pnas.org/content/83/19/7256.full.pdf