Evolution in Family Dendrobatidae (Poison Frogs): Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (3 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

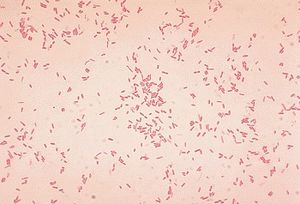

[[Image:a.hydrophila.jpg|thumb|300px|left|Gram stain of <i>Aeromonas hydrophila</i>, a bacterium known to infect frogs such as those in the Dendrobatidae family. Image [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aeromonas_hydrophila source]]] | [[Image:a.hydrophila.jpg|thumb|300px|left|Gram stain of <i>Aeromonas hydrophila</i>, a bacterium known to infect frogs such as those in the Dendrobatidae family. Image [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aeromonas_hydrophila source]]] | ||

The alkaloid toxicity in members of the Dendrobatidae family not only deters large predators, but also protects against microbial parasites. Hovey et. al. investigated this hypothesis, specifically in the case of the species <i>Oophaga pumilio</i>. The researchers tested the alkaloids of this species against <i>Aeromonas hydrophila</i> and <i>Klebsiella pneumoniae</i>, two bacterial pathogens known to infect frogs. Since alkaloid toxicity is derived from the diet, it was possible to collect frogs from five different locations (all within Costa Rica) with varied foodsource availability in order to acquire a range of alkaloid concentrations. After isolating the alkaloids from the frog specimens’ skin, extracts were presented to both of the pathogens. Growth inhibition was then assessed to find that differences in alkaloid presence aligned with differences in inhibition of the bacterias. This research by Hovey et. al. supports the fact that the toxins of dendrobatidae provide protection from harm not only by predators, but also by microbes. <br> | The alkaloid toxicity in members of the Dendrobatidae family not only deters large predators, but also protects against microbial parasites. Hovey et. al. investigated this hypothesis, specifically in the case of the species <i>Oophaga pumilio</i>. The researchers tested the alkaloids of this species against <i>Aeromonas hydrophila</i> and <i>Klebsiella pneumoniae</i>, two bacterial pathogens known to infect frogs. Since alkaloid toxicity is derived from the diet, it was possible to collect frogs from five different locations (all within Costa Rica) with varied foodsource availability in order to acquire a range of alkaloid concentrations. After isolating the alkaloids from the frog specimens’ skin, extracts were presented to both of the pathogens. Growth inhibition was then assessed to find that differences in alkaloid presence aligned with differences in inhibition of the bacterias. This research by Hovey et. al. supports the fact that the toxins of dendrobatidae provide protection from harm not only by predators, but also by microbes. <ref>[https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10886-018-0930-8 NR. Andriamaharavo, HM. Garraffo, et al. “Sequestered Alkaloid Defenses in the Dendrobatid Poison Frog Oophaga Pumilio Provide Variable Protection from Microbial Pathogens.” Journal of Chemical Ecology, Springer US, 10 Feb. 2018 ]</ref> <br> [[Image:frog_microbiome.jpg|thumb|300px|right|Mapping of bacterial families found on skin of <i>Colostethus panamansis</i> frogs by Martin H. et. al.]] | ||

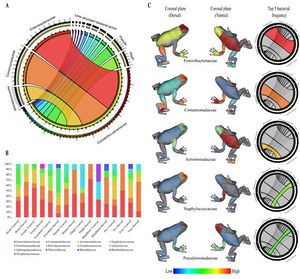

While there are microbes that are harmful to dendrobatidae frogs, species within the family also have their own beneficial skin microbiomes that aid in protection. Martin H. et. al. studied this in the species <i>Colostethus panamansis</i>. They were able to find five distinct bacterial families on the skin of organisms belonging to this species, which they mapped anatomically on a three dimensional model of the organism. The significance of these bacterial families, <i>Enterobacteriaceae, Comamonadaceae, Aeromonadaceae, Staphylococcaceae</i> and <i>Pseudomonadaceae</i>, comes from their potential to defend the frog from fungal infection. The species <i>Colostethus panamansis</i> has been severely affected by deadly chytridiomycosis, a disease caused by an infection of the fungus <i>Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis</i>. Analysis of microbial classification and comparison to a database of inhibitors to the fungal cause of chytridiomycosis in the five bacterial families found in non-infected organisms skin microbiome revealed that there is potential for the use of those bacteria in frog conservation. This research provides evidence of the evolutionary benefit of having a symbiotic microbiome by establishing a link between the frog’s skin bacteria and defense against <i>Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis</i>. <ref>[https://www.mdpi.com/2218-1989/10/10/406/htm Martin H., Christian, et al. “Metabolites from Microbes Isolated from the Skin of the Panamanian Rocket Frog Colostethus Panamansis (Anura: Dendrobatidae).” MDPI, Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute, 13 Oct. 2020]</ref> | |||

Latest revision as of 02:53, 10 December 2020

Introduction

The family Dendrobatidae, part of the class Amphibia, and more broadly, the kingdom Animalia, are a group of toxic frogs. These animals are commonly referred to as poison arrow frogs, dart poison frogs, or poison dart frogs. Frogs within this family are found living in the tropical climates of Central America and the northern portion of South America. They are usually small in size, and are known for their vivid coloration, although there are exceptions to this trait. Their diet consists of ants and mites, which research has suggested are suppliers of the precursor molecules that make up the amphibians toxins. Frogs in this family derive their common name from the Columbian practice of rubbing blow darts on the backs of frogs to coat them in poison for hunting. They produce some of the most highly toxic alkaloid poisons on earth. Many species’ toxins are strong enough to be lethal to vertebrates in even a micro dose. [1][2][3]

Evolution

Coloration and Toxicity

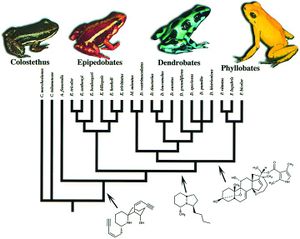

Members of the amphibian family Dendrobatidae are considered to be aposematic, meaning their coloration serves as an adverse warning that protects them from predation. For this notion to be true, it is implied that the frogs’ bright appearance and toxicity would have evolved in parallel. Research conducted by Summers and Clough set out to prove this hypothesis. Previously to this study, investigations of this hypothesis failed to account for phylogenetic relationships, which can cause a bias in results. Summers and Clough, however, made use of mitochondrial DNA from the gene regions cytochrome b, 12s RNA, and 16s RNA, in order to create a phylogenetic basis for their study. From this they developed four genera within the Dendrobatidae: Phyllobates, Dendrobates, Epipedobates, and Minyobates. This wide range of diversity within the family lead the researchers to a comparative method of analysis. For the twenty one representative species from each of the four genera examined in the study, data on toxicity was collected from literature, and coloration rated by both human observers and a computer program. When determining evolutionary correlation between the two phenomena, Comparative analysis on the data using models of both gradual and punctuated evolution showed that they were significantly correlated. The work of Summers and Clough effectively proved that frogs in the family Dendrobatidae, are in fact, aposematic. Their insight into the evolutionary processes in these animals are crucial, and provide an understanding of a constant relationship between two things that still are wildly varied within the group's population. [4]

Self Toxin Resistance

As with any toxic animal, Dendrobatidae frogs risk falling victim to their own poison. However, to combat this, an interesting feat of evolution has occurred. The nature of the alkalide poisons possessed by these amphibians is to target the nervous system, for example, as Tarvin et. al. specifically investigated in their study, epibatidine binds to and therefore blocks acetylcholine receptors. The mechanism they found in frogs with this toxin to avoid its effects was an alteration of a single amino acid. With just this one change that evolved three separate times in the poison frogs, epibatidine sensitivity was decreased. This solved the frogs’ problem of self-intoxication, but also happened to create another issue. The altered amino acid in the shared receptor of the toxin with acetylcholine also prevents the natural signaling that happens there and is needed for survival. But the frogs did however also find a solution to this problem. By expressing receptors from frogs in human cells, Tarvin et. al. were able to determine that there were additional amino acid changes that restored the acetylcholine signaling capabilities. But unlike the single substitution that created the toxin insensitivity, these replacements were different in various frog lineages. The work of Tarvin et. al. demonstrates how toxin resistance can evolve. It is in part a homoplasy, but also shows the divergence between different lineages. From this, we can see that resistance to their own toxins was advantageous for several of the ancestors of Dendrobatidae. [5]

Microbiome

The alkaloid toxicity in members of the Dendrobatidae family not only deters large predators, but also protects against microbial parasites. Hovey et. al. investigated this hypothesis, specifically in the case of the species Oophaga pumilio. The researchers tested the alkaloids of this species against Aeromonas hydrophila and Klebsiella pneumoniae, two bacterial pathogens known to infect frogs. Since alkaloid toxicity is derived from the diet, it was possible to collect frogs from five different locations (all within Costa Rica) with varied foodsource availability in order to acquire a range of alkaloid concentrations. After isolating the alkaloids from the frog specimens’ skin, extracts were presented to both of the pathogens. Growth inhibition was then assessed to find that differences in alkaloid presence aligned with differences in inhibition of the bacterias. This research by Hovey et. al. supports the fact that the toxins of dendrobatidae provide protection from harm not only by predators, but also by microbes. [6]

While there are microbes that are harmful to dendrobatidae frogs, species within the family also have their own beneficial skin microbiomes that aid in protection. Martin H. et. al. studied this in the species Colostethus panamansis. They were able to find five distinct bacterial families on the skin of organisms belonging to this species, which they mapped anatomically on a three dimensional model of the organism. The significance of these bacterial families, Enterobacteriaceae, Comamonadaceae, Aeromonadaceae, Staphylococcaceae and Pseudomonadaceae, comes from their potential to defend the frog from fungal infection. The species Colostethus panamansis has been severely affected by deadly chytridiomycosis, a disease caused by an infection of the fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis. Analysis of microbial classification and comparison to a database of inhibitors to the fungal cause of chytridiomycosis in the five bacterial families found in non-infected organisms skin microbiome revealed that there is potential for the use of those bacteria in frog conservation. This research provides evidence of the evolutionary benefit of having a symbiotic microbiome by establishing a link between the frog’s skin bacteria and defense against Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis. [7]

Conclusion

The family Dendrobatidae are an incredible group of species. Besides the beauty of their striking colors, they can be commended for their successful evolutionary methods for protection. The ability to develop extremely potent toxins from the ants they feed on serves them well as a deterrent to predators and microbial pathogens. Their resistance to self-intoxication is also a crafty advantage that is critical to their survival. Overall, the evolution of this family is a very interesting topic that is still being explored today.

References

- ↑ University of Michigan Museum of Zoology Animal Diversity Web - Dendrobatidae

- ↑ Amphibiaweb.org - Dendrobatidae

- ↑ Summers, K, and M E Clough. “The Evolution of Coloration and Toxicity in the Poison Frog Family (Dendrobatidae).” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, The National Academy of Sciences, 22 May 2001

- ↑ Summers, K, and M E Clough. “The Evolution of Coloration and Toxicity in the Poison Frog Family (Dendrobatidae).” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, The National Academy of Sciences, 22 May 2001

- ↑ Tarvin, Rebecca D., et al. “Interacting Amino Acid Replacements Allow Poison Frogs to Evolve Epibatidine Resistance.” Science, American Association for the Advancement of Science, 22 Sept. 2017

- ↑ NR. Andriamaharavo, HM. Garraffo, et al. “Sequestered Alkaloid Defenses in the Dendrobatid Poison Frog Oophaga Pumilio Provide Variable Protection from Microbial Pathogens.” Journal of Chemical Ecology, Springer US, 10 Feb. 2018

- ↑ Martin H., Christian, et al. “Metabolites from Microbes Isolated from the Skin of the Panamanian Rocket Frog Colostethus Panamansis (Anura: Dendrobatidae).” MDPI, Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute, 13 Oct. 2020

Edited by Sydney McCallie, student of Joan Slonczewski for BIOL 116 Information in Living Systems, 2020, Kenyon College.