The Structure and Function of Ebola Treatment Units: Difference between revisions

| Line 57: | Line 57: | ||

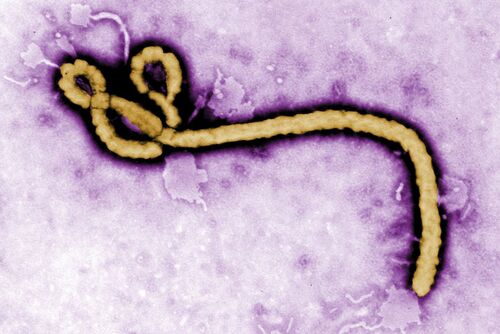

[[Image:Ebolapurpleimage.jpg|thumb|400px|right|A transmission electron microscopy image of the Ebola virion. Photo credit: [https://www.wsj.com/articles/ebola-in-congo-starts-scramble-to-contain-outbreak-1494858534/ The Wall Street Journal]]] | [[Image:Ebolapurpleimage.jpg|thumb|400px|right|A transmission electron microscopy image of the Ebola virion. Photo credit: [https://www.wsj.com/articles/ebola-in-congo-starts-scramble-to-contain-outbreak-1494858534/ The Wall Street Journal]]] | ||

<br> | |||

<br> | <br> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

Revision as of 22:55, 14 April 2024

Introduction

The genus ebolavirus is responsible for the cause of Ebola Virus Disease (EVD), a hemorrhagic fever virus in humans.[1] The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) classifies Ebola as a Category A select agent, making it a “high-priority agent” as it threatens national security. [2] Ebolaviruses (EBOV) belong to the virus family Filoviridae which it shares with Marburgvirus and Cuevavirus.[3] EBOV genomes consist of non-segmented, single-stranded RNA structures that includes seven open reading frames.[4][5] The EBOV genome is approximately 18.9 kilobases long.[6]

The EBOV genome encodes for seven genes each containing its own open reading frame.[7][8][9]

The seven gene all aid in the viral entry and replication of the virus:

1) Glycoproteins (GPs) bind to the host's receptors on the cell's surface to insert its viral genome.

2) The Ebola Matrix Protein (VP40) gives EBOV its filamentous shape and directs the budding of enveloped viruses.

3) Nucleoproteins are subunits of the Nucleocapsid that as whole protects the viral genome.

4) VP35, VP30, and VP24 proteins play roles in the formation of EBOVs helical nucleocapsid

5) The Polymerase (L) Protein is responsible for creating several copies of the RNA genome within hosts cells

GPs have been identified as a target for vaccine development, as their outward position on EBOV surfaces make them visible to antibodies.<ref>Credit. (n.d.-a). Ebola virus. Baylor College of Medicine. https://www.bcm.edu/departments/molecular-virology-and-microbiology/emerging-infections-and-biodefense/specific-agents/ebola-virus</rev> A major hope of vaccine development for EVD is to create a treatment that allows the binding of antibodies to non-carbohydrated regions of viral protein.[3] As of 2019, the very first FDA-approved Ebola vaccine called Ervebo has been approved and released for the use of people eighteen years or older.<Commissioner, O. of the. (n.d.). First FDA-approved vaccine for the prevention of ebola virus disease, marking a critical milestone in public health preparedness and response. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/first-fda-approved-vaccine-prevention-ebola-virus-disease-marking-critical-milestone-public-health</rev> Exposure to the GP in humans allows for the neutralization of antibodies, along with the restraint of viral attachment and fusion to host receptors. <rev>Malenfant JH, Joyce A, Choi MJ, et al. Use of Ebola Vaccine: Expansion of Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices to Include Two Additional Populations—United States, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2022;71:290–292</rev><rev>Lee JE, Saphire EO. Ebolavirus glycoprotein structure and mechanism of entry. Future Virol. 2009;4(6):621-635. doi: 10.2217/fvl.09.56. PMID: 20198110; PMCID: PMC2829775.</rev> Although Ervebo has saved many lives, the vaccine merely promotes the immunity of Zaire ebolavirus (ZEBOV)[24] With the possibility of high mutation rate frequencies of the EBOV genome and other infectious species, vaccine development is still underway in pharmaceutical companies.[27]

Along with Sudan ebolavirus (SUDV), ZEBOV is one of the most common outbreak-causing pathogens known for its inducement of the largest outbreak in West African history.[7] Without treatment, ZEBOV claims a fatality rate of up to 90%, making it the most lethal strain of EVD.[7] Although the fatality rates vary from case to case, the current fatality rate of EVD has decreased significantly. EVD fatality rates continue to decline due to heightened awareness of its transmission mechanisms and effective treatments. Currently, the average fatality rate of EVD patients who receive treatment is about 50%.[7]

Symptoms

The onset of symptoms typically occurs between the incubation period of 2-21 days after exposure to EBOV.[9] At its early to mild stages, victims may experience the following flu-like symptoms: Vomiting, fever, headache, abdominal pain and diarrhea. Advanced EVD is indicative of the following symptoms all of which are fatal, bleeding from all orifices of the body, multi-organ failure, hypovolemic shock and coffee ground emesis.[10]

Jeanne Kantungo, a 38 year-old mother and Ebola survivor from The Democratic Republic of Congo, shares her experience with the exigency of Ebola, along with a short description of her symptoms.[8] In Kantugo’s interview with The International Rescue Committee, she states:

“It started with headaches...then blood all over my body. I was in the Ebola Treatment Center for two months. I felt so lonely. Doctors and nurses reassured me that I would recover and go home. Kids were sad when they saw me going. They thought I would die.”[8]

Transmission

The transmission of EBOV commonly occurs through direct contact of contaminated body fluids with mucous membranes and open wounds, as they are direct pathways to the bloodstream.[11] Although EBOV is not classified as an airborne virus, there is a lack of evidence to eliminate its ability to spread atypically via aerosols, infectious droplets present in the air. This mode of transmission, which mostly pertains to medical workers, has been thought to come about through medical procedures and aerosols released from gastrointestinal and respiratory tracts.[12] Following the termination of the West African outbreak was the re-emergence of EBOV within West African communities. The re-emergence of EBOV has been connected to persistent viral RNA, found in the ejaculatory fluids and breast milk of EVD survivors.[13] Due to undetectable levels of the virus in EVD survivors, the possibility that EBOV remains transmissible has been overlooked. According to Keita et al, 2019, Ebola survivors can carry viral RNA in bodily fluids such as breast milk and semen for up to 200 days.[13] Furthermore, approximately 69.2% of patients were reported to have tested positive after 3 to 6 months of being discharged from treatment centers.[13]

The History of Ebola

While the origins of Ebola are indefinite, the zoonotic disease has led scientists to believe that the initial hosts of the virus are fruit bats of the Pteropodidae family, also known as “old world bats.”[11][16] These megabats, found in various parts of Africa, are considered to be a natural reservoir of the pathogen. Other animals such as apes, forest antelopes, and porcupines are known to have been infected.[11] Ebola was most likely transmitted to humans via hunters who came in direct contact with the infected animals or sold them for consumption.[14]

The first Ebola case occurred during the year 1976 in Zaire, which is now known as the Democratic Republic of Congo, located near the Ebola River[17]. Following the initial case was an outbreak in Sudan which resulted in a mortality rate of roughly 53%.[17]Up until the year 2000, within sub-saharan Africa, Ebola primarily affected Central and East African countries.[17] 2014 marked the largest Ebola outbreak in history, initially spreading between Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone.[18] The outbreak resulted in the infection and death of tens of thousands of people. Zaire ebolavirus, the most acquired strain in the West African outbreak, expanded further westward, reaching the countries of Nigeria, Mali, and Senegal.[19] Between 1990 and 2016 Ebola cases were found within 6 countries outside of Africa: United States, United Kingdom, Spain, Russia, and Italy.[17] The cause of these cases mostly came from healthcare workers who were treating patients at Ebola treatment centers in Africa and lab accidents.[17] Ebola cases further arose from infected airline passengers and animals, specifically pigs and macaques from The Philippines.[17] Infected macaques which were imported to a primate holding facility in the United States, were responsible for the well known cases from Reston, Virginia.[17] The very last major Ebola outbreak which occurred in Uganda during the fall of 2022, ended months later in early 2023.[17] During this outbreak 164 total cases along with 77 deaths were reported.[17]

The Structure and Function of Ebola Treatment Units

In countries that lack quality healthcare infrastructures and knowledge about disease transmission, the support of global assistance has been evident through the outbreaks of Ebola. In response to the first Ebola case in West Africa, over 2,000 U.S. military personnel and about 24,655 CDC trained healthcare workers were deployed to work in African Ebola Treatment Units (ETUs).[18][23] The construction of the very first ETU, which was funded by the U.S. government, was built in Liberia.[23] In efforts to control the outbreak of Ebola, seven additional ETUs were erected in Liberia with the help of the U.S. government.[23]

The purpose of the ETU is to provide quality care for Ebola patients while simultaneously preventing transmission within the unit and the general public.[20] Although ETUs were created for treatment and prevention of Ebola, it also became a treatment center for other coexisting diseases such as Malaria.[22] To fulfill its purpose, the structure of ETUs holds three risk areas.[20] The treatment unit itself is encompassed by two areas, the low-risk and high-risk zones.[20] The third risk area, which is enclosed by a fence, is established by the surrounding property on which the ETU is assembled.[20] The design of ETUs constrict infectious zones to one concentrated area through a “unidirectional flow.”[20] This allows medical personnel to move from low risk to high risk areas.[20] High-risk zones are specifically located at the very center of ETUs and are confined by a double gate.[20]

Low-Risk Zone:

While the low-risk zone has areas for storage of equipment, treatments, and meeting rooms, its main purpose is to provide a safe space for the preparation of patient care.[20] As a staff-only area, the low-risk zone includes a space for doning, a place for medical personnel to suit up in personal protective equipment (PPE)

High-Risk Zone:

The high risk zone is the area designated for patient care.[20] All activities that may result in the transmission of Ebola take place within the high-risk zone. For instance, the collection of PPE and medical instruments are disposed of in this zone.[20] Clinical samples from patients are kept in “High-risk zone” laboratories.[20] Doffing areas, which are utilized for the removal of PPE, increase the vulnerability of infection amongst healthcare workers.[21] The elevated chances of contracting Ebola in doffing areas is partly due to the fact that the body is exposed to the infectious environment. During the process of doffing, there is close distance between a caretaker's clothes and contaminated bodily fluids on the surface of PPE.[21]

The Management of Patients and Healthcare Workers

The management of patients in ETUs comes at the cost of monitoring various variables in an attempt to provide quality healthcare. Isolation in ETUs can be stress inducing to patients as they experience great affliction, become separated from their loved ones, and sojourn in a busy environment.[20] For this reason, ETUs are kept clean and comfortable to give patients a sense of normalcy.[20] In pursuit of making ETUs a less intimidating environment for patients, the presence of community is not only accepted but strongly encouraged.[20] Despite the forbiddance of visitors within the unit, the community is permitted to watch ETU activity from a far.[20] Furthermore, Communication between visitors and patients are facilitated by mesh fences that keep an appropriate distance between them.[20] That being said, all patients are kept in the high-risk zone.[20]

The management of healthcare workers is equally important to that of patients as workers may experience fatigue and are constantly at risk of contraction.[20] When treating patients, all healthcare workers are expected to use PPE. The use of PPE requires all caretakers to wear gloves, gowns, and rubber boots.[20] PPE also includes the use goggles, masks, and face shields for face protection.[20] The management of healthcare workers is enhanced by the “buddy system,” a mechanism of healthcare surveillance which allows ETUs to take immediate action in case of an emergency.[20] The buddy system promotes the prevention of Ebola transmission to healthcare workers, by having two workers stay in each others proximity at all times.[20]

Conclusion

- ↑ Kadanali A, Karagoz G. An overview of Ebola virus disease. North Clin Istanb. 2015 Apr 24;2(1):81-86. doi: 10.14744/nci.2015.97269. PMID: 28058346; PMCID: PMC5175058.

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018a, April 4). CDC. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://emergency.cdc.gov/agent/agentlist-category.asp

- ↑ Kadanali A, Karagoz G. An overview of Ebola virus disease. North Clin Istanb. 2015 Apr 24;2(1):81-86. doi: 10.14744/nci.2015.97269. PMID: 28058346; PMCID: PMC5175058.

- ↑ Postigo-Hidalgo I, Fischer C, Moreira-Soto A, Tscheak P, Nagel M, Eickmann M, Drexler JF. Pre-emptive genomic surveillance of emerging ebolaviruses. Euro Surveill. 2020 Jan;25(3):1900765. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.3.1900765. PMID: 31992392; PMCID: PMC6988270.

- ↑ Aceti DJ, Ahmed H, Westler WM, Wu C, Dashti H, Tonelli M, Eghbalnia H, Amarasinghe GK, Markley JL. Fragment screening targeting Ebola virus nucleoprotein C-terminal domain identifies lead candidates. Antiviral Res. 2020 Aug;180:104822. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2020.104822. Epub 2020 May 21. PMID: 32446802; PMCID: PMC7894038.

- ↑ Postigo-Hidalgo I, Fischer C, Moreira-Soto A, Tscheak P, Nagel M, Eickmann M, Drexler JF. Pre-emptive genomic surveillance of emerging ebolaviruses. Euro Surveill. 2020 Jan;25(3):1900765. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.3.1900765. PMID: 31992392; PMCID: PMC6988270.

- ↑ PDB101: Molecule of the month: Ebola virus proteins. RCSB. (n.d.). https://pdb101.rcsb.org/motm/178

- ↑ Takamatsu Y, Kolesnikova L, Becker S. Ebola virus proteins NP, VP35, and VP24 are essential and sufficient to mediate nucleocapsid transport. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018 Jan 30;115(5):1075-1080. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1712263115. Epub 2018 Jan 16. PMID: 29339477; PMCID: PMC5798334.

- ↑ Jain S, Martynova E, Rizvanov A, Khaiboullina S, Baranwal M. Structural and Functional Aspects of Ebola Virus Proteins. Pathogens. 2021 Oct 15;10(10):1330. doi: 10.3390/pathogens10101330. PMID: 34684279; PMCID: PMC8538763.