Tectiviridae: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| (45 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Uncurated}} | {{Uncurated}} | ||

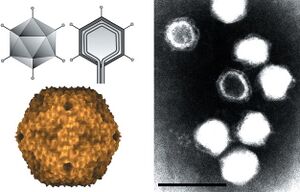

[[Image: | [[Image:Image tectiviridae enterobacterio phage prd1.jpg|thumb|300px|right|Legend. Image credit: San Martin, C. et al., (2001).]] | ||

==Classification== | ==Classification== | ||

Viruses; Varidnaviria; Bamfordvirae; Preplasmiviricota; Tectiliviricetes; Kalamavirales; Tectiviridae; Alphatectivirus; Alphatectivirus PRD1 | Viruses; Varidnaviria; Bamfordvirae; Preplasmiviricota; Tectiliviricetes; Kalamavirales; Tectiviridae; Alphatectivirus; Alphatectivirus PRD1 | ||

===Species=== | ===Species=== | ||

| Line 21: | Line 18: | ||

==Description and Significance== | ==Description and Significance== | ||

Alphatectivirus PRD1 is a bacteriophage known for its unique structural features. PRD1 has an icosahedral capsid, measuring about 66 nanometers in diameter, and unlike many bacteriophages, it possesses an internal lipid membrane situated beneath its protein shell. This rare characteristic among icosahedral viruses contributes to PRD1’s stability in diverse environments, including extreme pH and temperature conditions. Its linear double-stranded DNA genome, spanning approximately 15,000 base pairs, encodes multiple structural proteins that are crucial for the assembly and function of both the capsid and the internal membrane. | |||

PRD1's primary habitat involves environments where Gram-negative bacteria, such as Escherichia coli and Salmonella, thrive, which includes various soil and water ecosystems, as well as potential niches in the intestines of animals. This phage’s resilience across environmental conditions highlights its potential as a candidate for studies in bacteriophage therapy, particularly against antibiotic-resistant bacterial strains. PRD1’s bacteriophage characteristics allow it to target specific bacteria, raising the possibility of developing bacteriophage-based treatments that could serve as an alternative to conventional antibiotics. | |||

In addition to its relevance in combating bacterial infections, PRD1 has proven valuable in studies of DNA replication, protein synthesis, and virus-host interactions. Its relatively simple genome and replication mechanisms make it an ideal model for understanding virus assembly and gene regulation. Furthermore, PRD1’s unique lipid-containing capsid has inspired advancements in nanotechnology and drug delivery research, where scientists aim to mimic its stability and efficiency in viral assembly for use in biotechnological applications. | |||

==Genome Structure== | ==Genome Structure== | ||

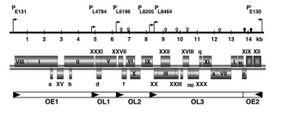

Single molecule of linear dsDNA that is | Single molecule of linear dsDNA that is 14927 bp, its entire sequence is known. The 5' ends of the DNA have covalently linked proteins. It also has inverted terminal repeats at both ends of the DNA sequence which serve as origins of replication. There are 31 genes in the genome but only 26 of them have a known protein product, the other 5 have listed under product "hypothetical protein". It also has 5 operons and 6 promoters, the extra promoter is due to the fact that it can be replicated from both ends of the DNA sequence due to the inverted terminal repeats. | ||

[[File:Structure..jpeg|frameless|caption]] | |||

==Cell Structure, Metabolism and Life Cycle== | ==Cell Structure, Metabolism and Life Cycle== | ||

| Line 39: | Line 39: | ||

==Ecology and Pathogenesis== | ==Ecology and Pathogenesis== | ||

Alphatectivirus PRD1 is a bacteriophage that infects Gram-negative bacteria, including species like Pseudomonas putida and Escherichia coli. It inhabits environments with dense bacterial populations, such as soil, water, and wastewater, where it contributes to microbial community dynamics by regulating bacterial populations. The virus relies on its bacterial hosts for replication, and in turn, it can influence ecological balance by controlling the density of specific bacterial species. It does not infect humans, animals, or plants, but is integral to microbial processes in these environments (Harvey, 2004). | |||

In terms of symbiosis, PRD1 is parasitic to bacteria, but it also promotes horizontal gene transfer, which helps increase genetic diversity among bacterial populations. By facilitating the exchange of genetic material, PRD1 indirectly supports microbial adaptability and evolution. The virus's activity can also contribute to biogeochemical cycles by lysing bacterial cells, which releases nutrients such as carbon and nitrogen back into the environment. These nutrients fuel microbial activity, promoting the growth of other organisms and contributing to the recycling of essential elements. | |||

PRD1 does not cause disease in humans, animals, or plants, as it specifically targets bacteria. Its "virulence" is limited to its interaction with bacterial hosts, where it uses unique viral mechanisms to penetrate and degrade the bacterial cell wall. This interaction results in bacterial lysis, which can influence microbial populations but does not lead to disease in higher organisms. PRD1’s role is more ecological, helping to maintain microbial diversity and supporting environmental nutrient cycles. | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/immunology-and-microbiology/enterobacteria-phage-prd1#:~:text=The%20capsid%20of%20Enterobacteria%20phage,are%20used%20for%20receptor%20recognition. | https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/immunology-and-microbiology/enterobacteria-phage-prd1#:~:text=The%20capsid%20of%20Enterobacteria%20phage,are%20used%20for%20receptor%20recognition. | ||

https://blog.addgene.org/viral-vectors-101-inverted-terminal-repeats | https://blog.addgene.org/viral-vectors-101-inverted-terminal-repeats | ||

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780128145159000448 | |||

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0923250824000330 | |||

https://www.uniprot.org/uniprotkb/P09009/entry | |||

https://www.mdpi.com/1999-4915/11/12/1134 | |||

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11577098 | |||

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11211187/ | |||

https://academic.oup.com/bioscience/article/49/10/781/222807?searchresult=1 | |||

https://viralzone.expasy.org/160?outline=all_by_species | |||

==Author== | ==Author== | ||

Latest revision as of 17:51, 22 November 2024

Classification

Viruses; Varidnaviria; Bamfordvirae; Preplasmiviricota; Tectiliviricetes; Kalamavirales; Tectiviridae; Alphatectivirus; Alphatectivirus PRD1

Species

NCBI: [1]

Enterobacteria phage PRD1

Description and Significance

Alphatectivirus PRD1 is a bacteriophage known for its unique structural features. PRD1 has an icosahedral capsid, measuring about 66 nanometers in diameter, and unlike many bacteriophages, it possesses an internal lipid membrane situated beneath its protein shell. This rare characteristic among icosahedral viruses contributes to PRD1’s stability in diverse environments, including extreme pH and temperature conditions. Its linear double-stranded DNA genome, spanning approximately 15,000 base pairs, encodes multiple structural proteins that are crucial for the assembly and function of both the capsid and the internal membrane.

PRD1's primary habitat involves environments where Gram-negative bacteria, such as Escherichia coli and Salmonella, thrive, which includes various soil and water ecosystems, as well as potential niches in the intestines of animals. This phage’s resilience across environmental conditions highlights its potential as a candidate for studies in bacteriophage therapy, particularly against antibiotic-resistant bacterial strains. PRD1’s bacteriophage characteristics allow it to target specific bacteria, raising the possibility of developing bacteriophage-based treatments that could serve as an alternative to conventional antibiotics.

In addition to its relevance in combating bacterial infections, PRD1 has proven valuable in studies of DNA replication, protein synthesis, and virus-host interactions. Its relatively simple genome and replication mechanisms make it an ideal model for understanding virus assembly and gene regulation. Furthermore, PRD1’s unique lipid-containing capsid has inspired advancements in nanotechnology and drug delivery research, where scientists aim to mimic its stability and efficiency in viral assembly for use in biotechnological applications.

Genome Structure

Single molecule of linear dsDNA that is 14927 bp, its entire sequence is known. The 5' ends of the DNA have covalently linked proteins. It also has inverted terminal repeats at both ends of the DNA sequence which serve as origins of replication. There are 31 genes in the genome but only 26 of them have a known protein product, the other 5 have listed under product "hypothetical protein". It also has 5 operons and 6 promoters, the extra promoter is due to the fact that it can be replicated from both ends of the DNA sequence due to the inverted terminal repeats.

Cell Structure, Metabolism and Life Cycle

Interesting features of cell structure; how it gains energy; what important molecules it produces.

Viruses like Alphatectivirus PRD1 do not have their own metabolism and are non-living entities that are unable to generate ATP and translate it to form proteins. Instead, Alphatectivirus PRD1 relies on the metabolism of host cells to provide energy and metabolic substances for their life cycles. It is icosahedral in shape, has no external envelope but does have a capsid along with spike proteins. It also has an inner membrane vesicle enclosed by the capsid that is made up of virus encoded proteins and lipids from the host cells plasma membrane.

Ecology and Pathogenesis

Alphatectivirus PRD1 is a bacteriophage that infects Gram-negative bacteria, including species like Pseudomonas putida and Escherichia coli. It inhabits environments with dense bacterial populations, such as soil, water, and wastewater, where it contributes to microbial community dynamics by regulating bacterial populations. The virus relies on its bacterial hosts for replication, and in turn, it can influence ecological balance by controlling the density of specific bacterial species. It does not infect humans, animals, or plants, but is integral to microbial processes in these environments (Harvey, 2004).

In terms of symbiosis, PRD1 is parasitic to bacteria, but it also promotes horizontal gene transfer, which helps increase genetic diversity among bacterial populations. By facilitating the exchange of genetic material, PRD1 indirectly supports microbial adaptability and evolution. The virus's activity can also contribute to biogeochemical cycles by lysing bacterial cells, which releases nutrients such as carbon and nitrogen back into the environment. These nutrients fuel microbial activity, promoting the growth of other organisms and contributing to the recycling of essential elements.

PRD1 does not cause disease in humans, animals, or plants, as it specifically targets bacteria. Its "virulence" is limited to its interaction with bacterial hosts, where it uses unique viral mechanisms to penetrate and degrade the bacterial cell wall. This interaction results in bacterial lysis, which can influence microbial populations but does not lead to disease in higher organisms. PRD1’s role is more ecological, helping to maintain microbial diversity and supporting environmental nutrient cycles.

References

https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/immunology-and-microbiology/enterobacteria-phage-prd1#:~:text=The%20capsid%20of%20Enterobacteria%20phage,are%20used%20for%20receptor%20recognition. https://blog.addgene.org/viral-vectors-101-inverted-terminal-repeats https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780128145159000448 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0923250824000330 https://www.uniprot.org/uniprotkb/P09009/entry https://www.mdpi.com/1999-4915/11/12/1134 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11577098 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11211187/ https://academic.oup.com/bioscience/article/49/10/781/222807?searchresult=1 https://viralzone.expasy.org/160?outline=all_by_species

Author

Page authored by Lee Hinson, Abi Miller, Mariella Dagdag, & Alexis Grimes, students of Prof. Bradley Tolar at UNC Wilmington.