Metallosphaera sedula: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

|||

| (29 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Uncurated}} | {{Uncurated}} | ||

==Classification== | ==Classification== | ||

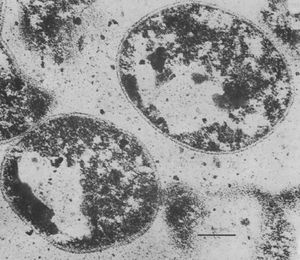

[[Image:M_sedula.jpg |thumb|right|alt=alt text|<i>Metallosphaera sedula</i>, Gertrud et. al.]] | |||

Domain: Archaea<br> | Domain: Archaea<br> | ||

Phylum: Crenarchaeota<br> | Phylum: Crenarchaeota<br> | ||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

Family: Sulfolobaceae<br> | Family: Sulfolobaceae<br> | ||

Genus: Metallosphaera<br> | Genus: Metallosphaera<br> | ||

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

==Description and Significance== | ==Description and Significance== | ||

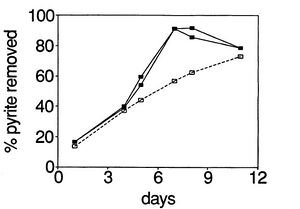

Originally isolated from a volcanic field in Italy, <i>Metallosphaera sedula</i> can be roughly translated into “metal mobilizing sphere” with the word “sedulus” meaning busy, describing its efficiency in mobilizing metals. <i> M. sedula</i> is a highly thermoacidophilic Achaean that is unusually tolerant of heavy metals | [[Image:Pyrite.jpg |thumb|left|alt=alt text|Percent pyrite removal by <i>M. sedula</i>(black) and control (white). Clark et. al.]] | ||

Due | Originally isolated from a volcanic field in Italy, <i>Metallosphaera sedula</i> can be roughly translated into “metal mobilizing sphere” with the word “sedulus” meaning busy, describing its efficiency in mobilizing metals. <i> M. sedula</i> is a highly thermoacidophilic Achaean that is unusually tolerant of heavy metals[1]. <br><br> | ||

Due to its ability to ability to oxidize pyrite (FeS<sub>2</sub>),<i> M. sedula</i> has the potential to be used for coal depyritization [3]. With increased awareness of the environmental impact of the combustion of coals, the idea of “clean coal” was born. While there are several focuses of “clean coal”, one of which is the removal of impurities, such as sulfur found in pyrite, prior to combustion. The combustion of sulfur leads to the formation of SO<sub>2</sub>, which has adverse health effects, and contributes to acid rain [4,5].<br> | |||

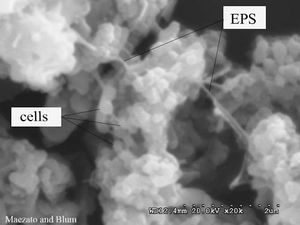

[[Image: | [[Image:Zam0030885610004.jpg |thumb|right|alt=alt text|<i>M. sedula</i> adhered to surface of FeS<sub>2</sub>. Auernik et al 2008]] | ||

Abiotic removal of pyrite from coal is currently the preferred method, as opposed to biotic extraction via microorganisms; however, the process is feasible. Other organisms have been studied for the purpose of coal depyritization (for example, <i>Thiobacillus ferroxidans</i>), however the process occurs at a slower rate than traditional abiotic removal. | |||

Abiotic removal of pyrite from coal is currently the preferred method, as opposed to biotic extraction via microorganisms; however, the process is feasible. Other organisms have been studied for the purpose of coal depyritization (for example, <i>Thiobacillus ferroxidans</i>), however the process occurs at a slower rate than traditional abiotic removal. [6] <i>M. sedula</i>, being thermophilic, is tolerant of higher temperatures which result in faster extraction rates than other organisms, and a strong candidate for future use in coal depyritization [3,6].<br> | |||

==Genome Structure== | ==Genome Structure== | ||

<i>M. sedula</i> contains a single, circular chromosome which is approximately 2.2 million base pairs in length. It encodes for around 2300 proteins, some of which are necessary for metal tolerance and adhesion. The function for 35% of the proteins is currently unknown and for this reason they are called hypothetical proteins. Based on sequence comparisons, <i>M. sedula</i> is most closely related to members of the genus <i>Sulfolobus</i>.[11] | |||

==Cell Structure, Metabolism and Life Cycle== | |||

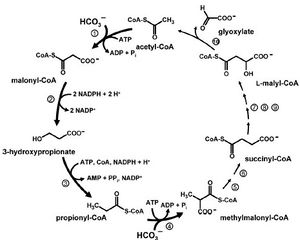

[[Image:3hpcycle.jpg|thumb|right|alt=alt text|3-hydroxypropionate cycle. Alber, Kung and Fuchs 2008]] | |||

<i>M. sedula</i> is a cocci, roughly 1um in diameter with pilus-like structures protruding from its surface when viewed via electron microscopy [1]. <br> | <i>M. sedula</i> is a cocci, roughly 1um in diameter with pilus-like structures protruding from its surface when viewed via electron microscopy [1]. <br> | ||

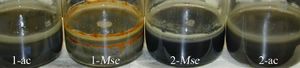

[[Image:Bioleach.jpg |thumb| | [[Image:Bioleach.jpg |thumb|left|alt=alt text|Chalcopyrite leaching. Left to right, control, <i>M. sedula</i> no H<sub>2</sub>, <i>M. sedula</i> in presence of H<sub>2</sub> and another control. Auernik and Kelly 2010]] | ||

<i>M. Sedula</i> is an obligate aerobe that grows best at 75C and pH 2.0 [1]. The high level of physiological diversity it displaces is relatively unique amongst extremophiles. It is capable of heterotrophic growth using complex organic molecules (with the exception of sugars [1]), autotrophic growth by the fixation of carbon dioxide in the presence of | <i>M. Sedula</i> is an obligate aerobe that grows best at 75C and pH 2.0 [1]. The high level of physiological diversity it displaces is relatively unique amongst extremophiles. It is capable of heterotrophic growth using complex organic molecules (with the exception of sugars [1]), autotrophic growth by the fixation of carbon dioxide in the presence of H<sub>2</sub> through an proposed modified 3-hydroxypropionate cycle [8], and its highest rates of growth are seen when grown mixotropically on casamino acids and metal sulfides [2]. The dissimilatory oxidation of iron and sulfur in <i>M. sedula</i>, driven by its membrane oxidases, is key to <i>M. sedula’s</i> ability to mobilize metals and bioleach. When grown in the presence of H<sub>2</sub>, the ability of <i>M. sedula</i> to leach copper from chalcopyrite (CuFeS<sub>2</sub>), is reduced [7]. <br> | ||

==Ecology and Pathogenesis== | |||

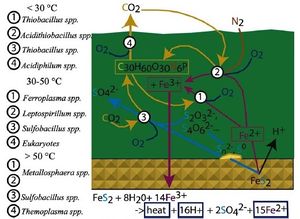

[[Image:AMD1234.jpg |thumb|left|alt=alt text|Iron, Sulfur and Carbon cycling in AMD. Baker and Banfield 2002]] | |||

<i>M. sedula</i> can be found in sulfur rich hot springs, volcanic fields, and in acid mine drainage (AMD) communities. These communities are characterized by high metal ion concentrations, low pH and high temperatures. [1] [9] [10]<br> | |||

Though the dissolution of pyrite in AMD is a natural process, it is accelerated the presence of acidophiles such as <i>M. sedula</i> that are found in these environments, thus leading to increased rates of acidification of water draining for active and abandoned mines. AMD communities are characterized by a diverse composition of microorganisms that fill available niches depending on their tolerance to temperature, metal resistance and pH. These communities display a complex symbiosis through the biogeochemical cycling of sulfur, iron, carbon and nitrogen. At high temperatures, <i>M. sedula</i> fills the niche of iron and sulfur oxidizer, a role that is filled by other acidophiles such as the mesophilic <i>Ferroplasma spp</i> and <i>Leptospirillum spp</i> at lower temperatures. [10]<br><br> | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| Line 49: | Line 54: | ||

5. http://www.epa.gov/acidrain/what/index.html<br> | 5. http://www.epa.gov/acidrain/what/index.html<br> | ||

6. [http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=MImg&_imagekey=B6V3B-498VNGX-14K-1&_cdi=5726&_user=1111158&_pii=0016236193903453&_origin=browse&_zone=rslt_list_item&_coverDate=12%2F31%2F1993&_sk=999279987&wchp=dGLbVzb-zSkWb&md5=c93ca7c9c6660f5076eb8a3223181dd8&ie=/sdarticle.pdf Peeples, T.L., and Kelly, R.M., “Bioenergetics of the metal/sulfur-oxidizingextreme thermoacidophile, Metallosphaera sedula”. <i> Fuel.</i> 1993. p. 1577-1752.]<br> | 6. [http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=MImg&_imagekey=B6V3B-498VNGX-14K-1&_cdi=5726&_user=1111158&_pii=0016236193903453&_origin=browse&_zone=rslt_list_item&_coverDate=12%2F31%2F1993&_sk=999279987&wchp=dGLbVzb-zSkWb&md5=c93ca7c9c6660f5076eb8a3223181dd8&ie=/sdarticle.pdf Peeples, T.L., and Kelly, R.M., “Bioenergetics of the metal/sulfur-oxidizingextreme thermoacidophile, Metallosphaera sedula”. <i> Fuel.</i> 1993. p. 1577-1752.]<br> | ||

7. [http://aem.asm.org/cgi/reprint/76/8/2668 Auernik, K and Kelly, R. “Impact of Molecular Hydrogen on Chalcopyrite Bioleaching by the Extremely Thermoacidophilic Archaeon <i>Metallosphaera sedula</i>”. <i>Applied and Environmental Microbiology</i>. 2010. p. 2668-2672.] | 7. [http://aem.asm.org/cgi/reprint/76/8/2668 Auernik, K and Kelly, R. “Impact of Molecular Hydrogen on Chalcopyrite Bioleaching by the Extremely Thermoacidophilic Archaeon <i>Metallosphaera sedula</i>”. <i>Applied and Environmental Microbiology</i>. 2010. p. 2668-2672.] <br> | ||

8. [http://jb.asm.org/cgi/reprint/190/4/1383?maxtoshow=&hits=10&RESULTFORMAT=&searchid=1&FIRSTINDEX=0&minscore=4000&resourcetype=HWCIT Alber, B., Kung, J., and Fuchs, G. "3-Hydroxypropionyl-Coenzyme A Synthetase from <i>Metallosphaera sedula</i>, an Enzyme Involved in Autotrophic CO2 Fixation". <i>Journal of Bacteriology</i> 2008. p. 1383-1389]<br> | |||

9. http://genome.jgi-psf.org/metse/metse.home.html<br> | |||

10. [http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1016/S0168-6496%2803%2900028-X/full Baker, B., and Banfield, J. "Microbial Communities in Acid Mine Drainage". <i>FEMS Microbial Ecology</i>. 2002. p. 139-152]<br> | |||

11. [http://aem.asm.org/cgi/content/abstract/74/3/682 Auernick, K. S., Maezato, Y., Blum, P. H., Kelly, R. M. “The Genome Sequence of the Metal-Mobilizing, Extremely Thermoacidophilic Archaeon <i>Metallosphaera sedula</i> Provides Insights into Bioleaching-Associated Metabolism”. <i>Applied and Environmental Microbiology</i>. 2008. p. 682-692] | |||

==Author== | ==Author== | ||

Latest revision as of 20:32, 23 April 2011

Classification

Domain: Archaea

Phylum: Crenarchaeota

Class: Thermoprotei

Order: Sulfolobales

Family: Sulfolobaceae

Genus: Metallosphaera

Species

|

NCBI: Taxonomy |

Metallosphaera sedula

Description and Significance

Originally isolated from a volcanic field in Italy, Metallosphaera sedula can be roughly translated into “metal mobilizing sphere” with the word “sedulus” meaning busy, describing its efficiency in mobilizing metals. M. sedula is a highly thermoacidophilic Achaean that is unusually tolerant of heavy metals[1].

Due to its ability to ability to oxidize pyrite (FeS2), M. sedula has the potential to be used for coal depyritization [3]. With increased awareness of the environmental impact of the combustion of coals, the idea of “clean coal” was born. While there are several focuses of “clean coal”, one of which is the removal of impurities, such as sulfur found in pyrite, prior to combustion. The combustion of sulfur leads to the formation of SO2, which has adverse health effects, and contributes to acid rain [4,5].

Abiotic removal of pyrite from coal is currently the preferred method, as opposed to biotic extraction via microorganisms; however, the process is feasible. Other organisms have been studied for the purpose of coal depyritization (for example, Thiobacillus ferroxidans), however the process occurs at a slower rate than traditional abiotic removal. [6] M. sedula, being thermophilic, is tolerant of higher temperatures which result in faster extraction rates than other organisms, and a strong candidate for future use in coal depyritization [3,6].

Genome Structure

M. sedula contains a single, circular chromosome which is approximately 2.2 million base pairs in length. It encodes for around 2300 proteins, some of which are necessary for metal tolerance and adhesion. The function for 35% of the proteins is currently unknown and for this reason they are called hypothetical proteins. Based on sequence comparisons, M. sedula is most closely related to members of the genus Sulfolobus.[11]

Cell Structure, Metabolism and Life Cycle

M. sedula is a cocci, roughly 1um in diameter with pilus-like structures protruding from its surface when viewed via electron microscopy [1].

M. Sedula is an obligate aerobe that grows best at 75C and pH 2.0 [1]. The high level of physiological diversity it displaces is relatively unique amongst extremophiles. It is capable of heterotrophic growth using complex organic molecules (with the exception of sugars [1]), autotrophic growth by the fixation of carbon dioxide in the presence of H2 through an proposed modified 3-hydroxypropionate cycle [8], and its highest rates of growth are seen when grown mixotropically on casamino acids and metal sulfides [2]. The dissimilatory oxidation of iron and sulfur in M. sedula, driven by its membrane oxidases, is key to M. sedula’s ability to mobilize metals and bioleach. When grown in the presence of H2, the ability of M. sedula to leach copper from chalcopyrite (CuFeS2), is reduced [7].

Ecology and Pathogenesis

M. sedula can be found in sulfur rich hot springs, volcanic fields, and in acid mine drainage (AMD) communities. These communities are characterized by high metal ion concentrations, low pH and high temperatures. [1] [9] [10]

Though the dissolution of pyrite in AMD is a natural process, it is accelerated the presence of acidophiles such as M. sedula that are found in these environments, thus leading to increased rates of acidification of water draining for active and abandoned mines. AMD communities are characterized by a diverse composition of microorganisms that fill available niches depending on their tolerance to temperature, metal resistance and pH. These communities display a complex symbiosis through the biogeochemical cycling of sulfur, iron, carbon and nitrogen. At high temperatures, M. sedula fills the niche of iron and sulfur oxidizer, a role that is filled by other acidophiles such as the mesophilic Ferroplasma spp and Leptospirillum spp at lower temperatures. [10]

References

1. Huber, G. ,Spinnler, C. , Gambacorta , A., and Stetter, K. “Metallosphaera sedula gen. and sp. nov. Represents a New Genus of Aerobic, Metal-Mobilizing, Thermoacidophilic Archaebacteria”. Systematic and Applied Microbiology. 1989. p. 38-47.

2. Auernik, K., and Kelly, R. “Physiological Versatility of the Extremely Thermoacidophilic Archaeon Metallosphaera sedula Supported by Transcriptomic Analysis of Heterotrophic, Autotrophic, and Mixotrophic Growth”. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2010. p. 931-935.

3. Clark, T., Baldi, F., And Olson, G. “Coal Depyritization by the Thermophilic Archaeon Metallosphaera sedula”. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 1993. p. 2375-2379.

4. http://www.epa.gov/oaqps001/sulfurdioxide/

5. http://www.epa.gov/acidrain/what/index.html

6. Peeples, T.L., and Kelly, R.M., “Bioenergetics of the metal/sulfur-oxidizingextreme thermoacidophile, Metallosphaera sedula”. Fuel. 1993. p. 1577-1752.

7. Auernik, K and Kelly, R. “Impact of Molecular Hydrogen on Chalcopyrite Bioleaching by the Extremely Thermoacidophilic Archaeon Metallosphaera sedula”. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2010. p. 2668-2672.

8. Alber, B., Kung, J., and Fuchs, G. "3-Hydroxypropionyl-Coenzyme A Synthetase from Metallosphaera sedula, an Enzyme Involved in Autotrophic CO2 Fixation". Journal of Bacteriology 2008. p. 1383-1389

9. http://genome.jgi-psf.org/metse/metse.home.html

10. Baker, B., and Banfield, J. "Microbial Communities in Acid Mine Drainage". FEMS Microbial Ecology. 2002. p. 139-152

11. Auernick, K. S., Maezato, Y., Blum, P. H., Kelly, R. M. “The Genome Sequence of the Metal-Mobilizing, Extremely Thermoacidophilic Archaeon Metallosphaera sedula Provides Insights into Bioleaching-Associated Metabolism”. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2008. p. 682-692

Author

Page authored by Stephanie Napieralski and Caitlin Miller, students of Prof. Jay Lennon at Michigan State University.

<-- Do not remove this line-->