Vibrio parahaemolyticus: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| (35 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Curated}} | |||

{{Biorealm Genus}} | {{Biorealm Genus}} | ||

| Line 8: | Line 9: | ||

Bacteria (domain); Proteobacteria (phylum); Gammaproteobacteria (class); Vibrionales (order); Vibrionaceae (family); Vibrio (genus); Vibrio parahaemolyticus (species) | Bacteria (domain); Proteobacteria (phylum); Gammaproteobacteria (class); Vibrionales (order); Vibrionaceae (family); Vibrio (genus); Vibrio parahaemolyticus (species) | ||

<br> | |||

Edited by Hau-Chen Lee, student of [mailto:ralarsen@ucsd.edu Rachel Larsen] and Kit Pogliano | |||

===Species=== | ===Species=== | ||

| Line 17: | Line 22: | ||

''Vibrio parahaemolyticus'' | ''Vibrio parahaemolyticus'' | ||

<br> | |||

Edited by Hau-Chen Lee, student of [mailto:ralarsen@ucsd.edu Rachel Larsen] and Kit Pogliano | |||

==Description and significance== | ==Description and significance== | ||

''Vibrio parahaemolyticus'' is a gram negative bacterium that is typically found in warm estuarine seawaters due to its halophilic (salt-requiring) characteristics. It is the number one leading cause of sea-food associated bacterial gastroenteritis in the United States. | ''Vibrio parahaemolyticus'' is a gram negative bacterium that is typically found in warm estuarine seawaters due to its halophilic (salt-requiring) characteristics. It is the number one leading cause of sea-food associated bacterial gastroenteritis in the United States. | ||

<br> | |||

''V. parahaemolyticus'' causes diarrhea upon ingestion. While the overwhelming majority of people acquire the infection by eating raw or undercooked seafood (particularly shellfish and oysters), an open wound exposed to warm seawater can facilitate ''V. parahaemolyticus'' infection. | ''V. parahaemolyticus'' causes diarrhea upon ingestion. While the overwhelming majority of people acquire the infection by eating raw or undercooked seafood (particularly shellfish and oysters), an open wound exposed to warm seawater can facilitate ''V. parahaemolyticus'' infection. | ||

<br> | |||

Isolation of ''V. parahaemolyticus'' is possible from cultures of stool, wound, or blood. Isolation from stool preferably involves a medium that contains thiosulfate, citrate, bile salts, and sucrose (TCBS agar). | Isolation of ''V. parahaemolyticus'' is possible from cultures of stool, wound, or blood. Isolation from stool preferably involves a medium that contains thiosulfate, citrate, bile salts, and sucrose (TCBS agar). | ||

<br> | |||

Edited by Hau-Chen Lee, student of [mailto:ralarsen@ucsd.edu Rachel Larsen] and Kit Pogliano | |||

==Genome structure== | ==Genome structure== | ||

| Line 71: | Line 86: | ||

<b>Replicon Name</b>: I<br> | <b>Replicon Name</b>: I<br> | ||

<b>Created</b>: 2003/03/10<br> | <b>Created</b>: 2003/03/10<br> | ||

<br> | |||

Edited by Hau-Chen Lee, student of [mailto:ralarsen@ucsd.edu Rachel Larsen] and Kit Pogliano | |||

==Cell structure and metabolism== | ==Cell structure and metabolism== | ||

<b>Cell Structure.</b> ''V. parahaemolyticus'' is a gram-negative bacterium, meaning that it has an outer membrane, inner membrane, and a thin cell wall made out of peptidoglycan that is located in the periplasm. The gram-negative cell wall may contain lipopolysaccharides, which is an important feature of pathogens and is composed of O-antigen repeating subunits, core polysaccharide, and lipid A anchor. | |||

<br> | |||

Edited by Hau-Chen Lee, student of [mailto:ralarsen@ucsd.edu Rachel Larsen] and Kit Pogliano | |||

==Ecology== | ==Ecology== | ||

<b>Cause and Symptoms.</b> ''V. parahaemolyticus'' is the leading cause of seafood-associated gastroenteritis in the United States. Human ingestion of ''V. parahaemolyticus'' causes various symptoms, including diarrhea, abdominal cramping, myalgias, self-reported fever, headache, vomiting, diarrhea with mucus, and bloody diarrhea (McLaughlin et al., 2005) In addition to self-limited gastroenteritis, ''V. parahaemolyticus'' infections also occur through wound exposure to organism, primary septicemia, and other infection sites (Daniels et al., 2000). | |||

<br> | |||

<b>Hosts.</b> ''V. parahaemolyticus''is most commonly found in oysters and shellfish, including human-controlled oyster farms. Doubling time of ''V. parahaemolyticus'' at ideal conditions is one of the shortest times known for bacteria (8 to 9 minutes). The fast replication rate implies that contaminated oysters with a small colony of ''V. parahaemolyticus'' will only need a few hours to grow to an infectious dose (Daniels et al., 2000). | |||

<br> | |||

<b>Virulence factors.</b> Thermostable direct hemolysin (encoded by <i>tdh</i> genes) and thermostable direct hemolysin-related hemolysin (encoded by <i>trh</i> genes) are produced by ''V. parahaemolyticus'' strains. Encoding of thermostable direct hemolysin virulence factors can cause beta-hemolysis of human erythrocytes, also known as the Kanagawa phenomenon. A strong link between possession of the <i>tdh</i> gene and incidents of gastroenteritis has been established in Japanese studies. Therefore, detection of <i>tdh</i> and <i>trh</i> genes is often used to determine the pathogenicity of ''V. parahaemolyticus'' strains (Martinez-Urtaza et al., 2004). | |||

<br> | |||

Edited by Hau-Chen Lee, student of [mailto:ralarsen@ucsd.edu Rachel Larsen] and Kit Pogliano | |||

==Application to Biotechnology== | ==Application to Biotechnology== | ||

<b>Compound Production.</b> No useful compounds or enzymes have been found to be produced by ''V. parahaemolyticus'', according to the latest research. | |||

<br> | |||

Edited by Hau-Chen Lee, student of [mailto:ralarsen@ucsd.edu Rachel Larsen] and Kit Pogliano | |||

==Current Research== | ==Current Research== | ||

<b>McLaughlin et al. (2005).</b> First reported cases of ''V. parahaemolyticus'' outbreak in cold-water marine environments. Rising seawater temperature may attribute to the outbreak. | |||

<br> | |||

<b>Martinez-Urtaza et al. (2004).</b> Comparing ''V. parahaemolyticus'' isolates from Spain with Asian and North American isolates. Results suggest that ''V. parahaemolyticus'' infections in Europe involve a unique and specific clone. | |||

<br> | |||

<b>Daniels et al. (2000).</b> First identification of ''V. parahaemolyticus'' serotype O3:K6 infection after outbreak in Texas. Authors attributed rising seawater temperatures and salinity levels to the ''V. parahaemolyticus'' outbreak. | |||

<br> | |||

Edited by Hau-Chen Lee, student of [mailto:ralarsen@ucsd.edu Rachel Larsen] and Kit Pogliano | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

[http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dbmd/diseaseinfo/vibrioparahaemolyticus_g.htm "Disease Listing, ''Vibrio parahaemolyticus'', General Info". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. October 25, 2005.] | [http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dbmd/diseaseinfo/vibrioparahaemolyticus_g.htm "Disease Listing, ''Vibrio parahaemolyticus'', General Info". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. October 25, 2005.] | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

[http://phil.cdc.gov/phil/home.asp CDC Public Health Image Library] | [http://phil.cdc.gov/phil/home.asp CDC Public Health Image Library] | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

[http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?db=Genome Entrez Genome] | [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?db=Genome Entrez Genome] | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

[http://130.14.29.110/Taxonomy/ NCBI Taxonomy] | [http://130.14.29.110/Taxonomy/ NCBI Taxonomy] | ||

<br> | |||

[http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/full/284/12/1541 Daniels, N.A., B. Ray, et al. (2000). "Emergence of a new Vibrio parahaemolyticus serotype in raw oysters: A prevention quandary." <u>Jama</u> <b>284</b>(12): 1541-5.] | |||

<br> | |||

[http://content.nejm.org/cgi/content/abstract/353/14/1463 McLaughlin, J.B., A. DePaola, et al. (2005). "Outbreak of Vibrio parahaemolyticus gastroenteritis associated with Alaskan oysters." <u>N Engl J Med</u> <b>353</b>(14): 1463-70] | |||

<br> | |||

[http://jcm.asm.org/cgi/content/full/42/10/4672?view=long&pmid=15472326 Martinez-Urtaza, J., A. Lozano-Leon, et al. (2004) "Characterization of pathogenic Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolates from clinical sources in Spain and comparison with Asian and North American pandemic isolates." <u>J Clin Microbiol</u> <b>42</b>(10):4672-8] | |||

Edited by Hau-Chen Lee, student of [mailto:ralarsen@ucsd.edu Rachel Larsen] and Kit Pogliano | Edited by Hau-Chen Lee, student of [mailto:ralarsen@ucsd.edu Rachel Larsen] and Kit Pogliano | ||

Latest revision as of 20:21, 6 May 2011

A Microbial Biorealm page on the genus Vibrio parahaemolyticus

Classification

Higher order taxa

Bacteria (domain); Proteobacteria (phylum); Gammaproteobacteria (class); Vibrionales (order); Vibrionaceae (family); Vibrio (genus); Vibrio parahaemolyticus (species)

Edited by Hau-Chen Lee, student of Rachel Larsen and Kit Pogliano

Species

|

NCBI: Taxonomy |

Vibrio parahaemolyticus

Edited by Hau-Chen Lee, student of Rachel Larsen and Kit Pogliano

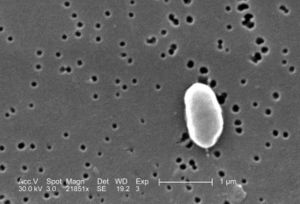

Description and significance

Vibrio parahaemolyticus is a gram negative bacterium that is typically found in warm estuarine seawaters due to its halophilic (salt-requiring) characteristics. It is the number one leading cause of sea-food associated bacterial gastroenteritis in the United States.

V. parahaemolyticus causes diarrhea upon ingestion. While the overwhelming majority of people acquire the infection by eating raw or undercooked seafood (particularly shellfish and oysters), an open wound exposed to warm seawater can facilitate V. parahaemolyticus infection.

Isolation of V. parahaemolyticus is possible from cultures of stool, wound, or blood. Isolation from stool preferably involves a medium that contains thiosulfate, citrate, bile salts, and sucrose (TCBS agar).

Edited by Hau-Chen Lee, student of Rachel Larsen and Kit Pogliano

Genome structure

Shotgun sequencing of Vibrio parahaemolyticus AQ3810 is unfinished. To this date, 2 plasmids (pO3K6 and pSA19) and 2 chromosomes (chromosome I and chromosome II) are completely sequenced. The importance of plasmids to the organism's lifestyle is unknown at this point.

Vibrio parahaemolyticus AQ3810 (unfinished)

DNA structure: other

Length: 5,771,228 nt

Replicon Type: chromosome

Created: 2007/01/11

Vibrio parahaemolyticus plasmid pO3K6, complete sequence

DNA structure: circular

Length: 8,784 nt

Replicon Type: plasmid

Replicon Name: pO3K6

Created: 2000/06/29

Vibrio parahaemolyticus plasmid pSA19, complete sequence

DNA structure: circular

Length: 4,839 nt

Replicon Type: plasmid

Replicon Name: pSA19

Created: 1996/05/23

Vibrio parahaemolyticus RIMD 2210633 chromosome II, complete sequence

DNA structure: circular

Length: 1,877,212 nt

Replicon Type: chromosome

Replicon Name: II

Created: 2003/03/10

Vibrio parahaemolyticus RIMD 2210633 chromosome I, complete sequence

DNA structure: circular

Length: 3,288,558 nt

Replicon Type: chromosome

Replicon Name: I

Created: 2003/03/10

Edited by Hau-Chen Lee, student of Rachel Larsen and Kit Pogliano

Cell structure and metabolism

Cell Structure. V. parahaemolyticus is a gram-negative bacterium, meaning that it has an outer membrane, inner membrane, and a thin cell wall made out of peptidoglycan that is located in the periplasm. The gram-negative cell wall may contain lipopolysaccharides, which is an important feature of pathogens and is composed of O-antigen repeating subunits, core polysaccharide, and lipid A anchor.

Edited by Hau-Chen Lee, student of Rachel Larsen and Kit Pogliano

Ecology

Cause and Symptoms. V. parahaemolyticus is the leading cause of seafood-associated gastroenteritis in the United States. Human ingestion of V. parahaemolyticus causes various symptoms, including diarrhea, abdominal cramping, myalgias, self-reported fever, headache, vomiting, diarrhea with mucus, and bloody diarrhea (McLaughlin et al., 2005) In addition to self-limited gastroenteritis, V. parahaemolyticus infections also occur through wound exposure to organism, primary septicemia, and other infection sites (Daniels et al., 2000).

Hosts. V. parahaemolyticusis most commonly found in oysters and shellfish, including human-controlled oyster farms. Doubling time of V. parahaemolyticus at ideal conditions is one of the shortest times known for bacteria (8 to 9 minutes). The fast replication rate implies that contaminated oysters with a small colony of V. parahaemolyticus will only need a few hours to grow to an infectious dose (Daniels et al., 2000).

Virulence factors. Thermostable direct hemolysin (encoded by tdh genes) and thermostable direct hemolysin-related hemolysin (encoded by trh genes) are produced by V. parahaemolyticus strains. Encoding of thermostable direct hemolysin virulence factors can cause beta-hemolysis of human erythrocytes, also known as the Kanagawa phenomenon. A strong link between possession of the tdh gene and incidents of gastroenteritis has been established in Japanese studies. Therefore, detection of tdh and trh genes is often used to determine the pathogenicity of V. parahaemolyticus strains (Martinez-Urtaza et al., 2004).

Edited by Hau-Chen Lee, student of Rachel Larsen and Kit Pogliano

Application to Biotechnology

Compound Production. No useful compounds or enzymes have been found to be produced by V. parahaemolyticus, according to the latest research.

Edited by Hau-Chen Lee, student of Rachel Larsen and Kit Pogliano

Current Research

McLaughlin et al. (2005). First reported cases of V. parahaemolyticus outbreak in cold-water marine environments. Rising seawater temperature may attribute to the outbreak.

Martinez-Urtaza et al. (2004). Comparing V. parahaemolyticus isolates from Spain with Asian and North American isolates. Results suggest that V. parahaemolyticus infections in Europe involve a unique and specific clone.

Daniels et al. (2000). First identification of V. parahaemolyticus serotype O3:K6 infection after outbreak in Texas. Authors attributed rising seawater temperatures and salinity levels to the V. parahaemolyticus outbreak.

Edited by Hau-Chen Lee, student of Rachel Larsen and Kit Pogliano

References

CDC Public Health Image Library

Edited by Hau-Chen Lee, student of Rachel Larsen and Kit Pogliano