Botox for Cosmetic Use: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 39: | Line 39: | ||

The first successful uses of BTX-A on glabellar frown lines are also attributed to Dr. Scott in the mid-1980s; however, the first systematic study of BTX-A in facial rejuvenation was not carried out until the early 1990s by Drs. Alastair and Jean Carruthers (Carrathurs, 2002). Following this study other dermatologists followed suit. By 1997, the off-label (legal but unregulated) use of the toxin for cosmetic use was so strong that the supply in the US ran out (Mapes, 2007 and Preidt, 2012). In 2002, BOTOX Cosmetic was approved for use in treating glabellar frown lines and use skyrocketed. In its first year after FDA approval, between 1.2 and 1.6 million people underwent treatment for cosmetic use (Cote et al, 2005). By 2006, Botox sales exceeded $1 billion, about half of which were for cosmetic use. Botox is now the most popular non-surgical cosmetic treatment in the US (Mapes, 2007). | The first successful uses of BTX-A on glabellar frown lines are also attributed to Dr. Scott in the mid-1980s; however, the first systematic study of BTX-A in facial rejuvenation was not carried out until the early 1990s by Drs. Alastair and Jean Carruthers (Carrathurs, 2002). Following this study other dermatologists followed suit. By 1997, the off-label (legal but unregulated) use of the toxin for cosmetic use was so strong that the supply in the US ran out (Mapes, 2007 and Preidt, 2012). In 2002, BOTOX Cosmetic was approved for use in treating glabellar frown lines and use skyrocketed. In its first year after FDA approval, between 1.2 and 1.6 million people underwent treatment for cosmetic use (Cote et al, 2005). By 2006, Botox sales exceeded $1 billion, about half of which were for cosmetic use. Botox is now the most popular non-surgical cosmetic treatment in the US (Mapes, 2007). | ||

[[File:.jpg]] | [[File:Femaleskinaging.jpg]] | ||

Revision as of 01:13, 10 May 2012

What is Botox and how is it used?

MICROBIAL SOURCE OF BOTULINUM TOXIN

Botulinum toxin is one of the most lethal substances made by Clostridium botulinum. Unlike most microbial killers that invade and infect our bodies, Clostridium botulinum does not cause disease as most pathogenic bacteria do (Ingraham, p.233). C. botulinum produces its toxin wherever it may be living and when we consume it we become sick or die. Two main characteristics make c. botulinum hazardous: it is an anaerobe, and it produces endospores (Ingraham, p.233). Because c. botulinum is Anaerobic organisms such as c.botulinum do not require oxygen for growth; therefore, they can grow in oxygen free places such as canned goods. The ability to produce endospores makes it easier to survive under extreme harsh conditions. Endospores form when bacteria run out of nutrients; hence, they germinate, grow, and produce the botulinum toxin called Botox. Active ingredients in Botox and Botox Cosmetic include botulinum toxin type A, while inactive ingredients include human albumin and sodium chloride (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2011). Botox is very potent; it inhibits neurons and causes paralysis.

HOW BOTULINUM TOXIN WORKS

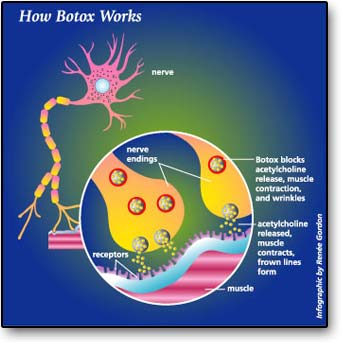

Botox is very lethal and a small amount of the substance is enough to cause harm to humans. Botulinum toxin is made up of just two ordinary proteins joined together by easily broken chemical bonds—sulfur-to-sulfur bonds between cysteine amino acids in two proteins (Ingraham, p.234). The heavier protein is responsible for seeking and finding the exact spot where nerves contact muscles. When botulinum toxin arrives at this critical junction, a lighter protein that is a protein-destroying enzyme called protease attacks the neuromuscular junction. Consequently, when the neuromuscular junction is destroyed, the neurotransmitter acetylcholine cannot bind to it. Botox works by neuromuscular inhibition of acetylcholine. Without the intervention of acetylcholine, muscle contraction and wrinkles will take place.

USES AND SIDE EFFECTS

Botulinum toxin is an ingredient in the spa treatment Botox that has found its way into beauty salons through the medical world. Botox is a powerful muscle relaxant that is used in small doses because it is potent. Botox has different medical uses for ailments such as spasticity and muscle pain. One of the most common uses is injecting it near wrinkles because it relaxes the surrounding muscles and causes wrinkles to disappear. Injections are an effective treatment that usually improves the appearance of frown lines between the eyes as well as the necklines and will make you look younger. Aging skin is an issue of concern to many patients. Purified Botulinum toxin type A is a neurotoxin used to paralyze various muscle groups of the face for cosmetic improvement of wrinkles (Helfrich, Sachs, Voorhees, 2008). Paralysis of small muscle groups such as the forehead and glabella allow patients to improve their look and look more youthful. The effects of Botox last from 3 to 6 months; however, side effects of Botox include pain, bruising, and paralysis of the nerves that control eyelid function.

Botox may cause serious side effects that can be life threatening. Possible side effects include: problems breathing or swallowing and spread of toxin effects (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2011). Botox problems can arise hours, days, or months after the injection because the muscles involved in breathing and swallowing can become weak after the infection. As a result, death can happen as muscles start to fail and not contribute to vital respiratory actions like breathing. People who may be at greater risk are those with serious breathing problems because muscles in the neck contribute to breathing. Similarly, people who usually have problems swallowing are at greater risk of getting swallowing problems. People who cannot swallow well may need a feeding tube to receive food and water, but this is very risky because food or liquids may go into the lungs. In addition, the effect of Botox may also affect areas of the body that are away from the injection site. The spread of toxin effects may lead to symptoms such as loss of strength and muscle weakness all over the body, double vision, blurred vision and drooping eyelids, hoarseness or change or loss of voice (dysphonia), trouble saying words clearly (dysarthria), loss of bladder control (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2011). Botox cosmetic is not recommended for use in children younger than 18 years of age. Botox cosmetic is an injection that your doctor will give you into your affected muscles. In addition, other side effects of Botox and Botox cosmetic include: dry mouth, tiredness, headache, neck pain, eye problems. Allergic reaction to Botox include: itching, rash, red itchy welts, wheezing, asthma symptoms, or dizziness or feeling faint (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2011). Doctors usually change the dose of Botox Cosmetic injection until they find a good-fit for their patient; however, the patient should notify the doctor as soon as they start to experience any of the problems mentioned above.

History and Development:

The study of Botulinum toxin spans from the early 19th century and continues today. There have been studies of the toxin for use in warfare, medicine, and cosmetics. This section traces the history and development of Botox.

BOTULINUM TOXIN FIRST STUDIED: KERNER

The toxin produced by Clostridium botulinum was first studied around the Napoleonic Wars (1817-1822) by German Physician Justinus Kerner. A sharp increase in food poisoning related deaths in Welzheim was attributed to the consumption of blood sausages. After conducting experiments both himself and animals, Kerner deduced that the “sausage poison” that was killing people in rural Germany was produced under anaerobic conditions, attacked the nervous system, and was lethal in small doses (Kopera, 2011). Kerner also suggested that the toxin could possibly be used as a therapeutic agent (Kopera, 2011).

BOTULINUM TOXIN FIRST IDENTIFIED: VAN ERMENGEM

About eight decades later in 1895, Professor Emile Pierre van Ermengem identified Clostridium botulinum (first named Bacillus botulinus). A band of musicians fell ill in Ellezelles, Belgium after eating ham products. Ermengem conducted experiments on both the pork and the tissue of the three fatalities attributed to the event. He discovered the link between the symptoms of the “sausage poisoning” to bacteria (Clostridium botulinum) found in raw, salted pork (Kopera, 2011). From this point on, Botulinum toxin has been the subject of research because of it strong effect on the nervous system and possible therapeutic uses(Allergan, 2010).

EARLY 20TH CENTURY RESEARCH AND BIOLOGICAL WEAPONS

In the 1920s, crude forms of BTX-A (the botulinum toxin used in Botox and Dysport) were obtained by Dr. Herman Sommer at University of California- San Francisco. During WWII, the US Government took this crude form of the toxin and attempted to create biological weapons from it at Fort Detrick, MD. While botulinum toxin was not successfully used in biological warfare during WWII, research on botulinum toxin at Fort Detrick eventually led to the isolation of pure, crystalline BTX-A for use on humans by Dr. Edward Schantz and his colleagues in 1946 (Kopera, 2011 and Carrathurs, 2002).

THERAPUTIC USE OF BTX-A AND RISE OF BOTOX

Starting in the 50s and 60s, the potential of utilizing the toxin in medicine became realized. In the 1950s, Dr. Vernon Brook showed that BTX-A blocks acetylcholine from motor nerve endings (Carrathurs, 2002). This discovery led Dr. Alan Scott of the Smith-Kettlewell Eye Research Foundation to begin to experiment with using BTX-A to alleviate symptoms of strabismus (cross-eyed syndrome) in monkeys. Scott worked along with Schantz to create a form of BTX-A suitable for use on humans and started Oculinum, Inc. to study the efficacy in treating strabismus in human volunteers (Allergan, 2010). In 1979, he acquired government approval. In 1980, he published a paper providing convincing evidence of BTX-A as both a safe and effective alternative to surgery in correcting strabismus and suggested that BTX-A could possibly be useful in treating other health issues marked by hyperactivity or muscle spasms (Carruthers, 2002). In 1988, Allergan, Inc. acquired the rights to distribute Dr. Scott’s BTX-A product called Oculinum, eventually buying Scott’s company and changing the name of the drug to BOTOX in 1989 once the FDA approved its use in treating strabismus and blepharospasm or involuntary blinking. Botox was also approved for the treatment of cervical dystonia or muscle spasms in the neck and shoulders in 2000 (Allergan, 2010).

BOTOX FOR COSMETIC USE

The first successful uses of BTX-A on glabellar frown lines are also attributed to Dr. Scott in the mid-1980s; however, the first systematic study of BTX-A in facial rejuvenation was not carried out until the early 1990s by Drs. Alastair and Jean Carruthers (Carrathurs, 2002). Following this study other dermatologists followed suit. By 1997, the off-label (legal but unregulated) use of the toxin for cosmetic use was so strong that the supply in the US ran out (Mapes, 2007 and Preidt, 2012). In 2002, BOTOX Cosmetic was approved for use in treating glabellar frown lines and use skyrocketed. In its first year after FDA approval, between 1.2 and 1.6 million people underwent treatment for cosmetic use (Cote et al, 2005). By 2006, Botox sales exceeded $1 billion, about half of which were for cosmetic use. Botox is now the most popular non-surgical cosmetic treatment in the US (Mapes, 2007).

MORE RECENT APPLICATIONS

In 2004, Botox was approved to treat excessive underarm sweating in the case that topical medicines prove ineffective. In 2010, Botox was also approved to treat muscle stiffness in the elbows, wrists, and finger muscles of those afflicted with upper limb spasticity. Further research is currently being conducted to see if Botox is effective in treating other ailments (Allergan, 2010).

Controversies in Cosmetic Use

Botox in cosmetic use has caused huge controversy in recent years. Most of the controversies revolve around its side effects, for example facial paralysis, double or blurred vision, severe allergic reactions or difficulty breathing and swallowing. This has cast a negative light on the companies, which distribute Botox in the United States.

BOTOX COMPANIES

There two biggest medical companies involved in the distribution of Botox in the United States. At this point Allergan Inc. is the biggest distributor of Botox Cosmetics, an injectable anti-wrinkle treatment, with worldwide sales of $1.3 billion. Not as big but catching up is the company Medicis, who markets Dysport, an anti-wrinkle shot. Dysport only has sales of $189 million worldwide, but it also has not been on the market as long. The FDA only recently approved it in 2009 (“To Take on Botox”, 2010).

LAWSUITS DUE TO SIDE EFFECTS

Both Allergan and Medicis, are constantly in the news due to their involvement with Botox. In 2008, Allergan Inc. was sued by Botox users, who claimed that they the company had not properly made people aware of the dangers of using the toxin. The lawsuit began as Botox users sued the company after three people died and others were left with severe disabilities after experiencing its side effects. Of the three deaths, one death resulted from the use of Botox for cosmetic reasons. An older woman had gotten injections for wrinkles around her mouth, which led to her having troubles breathing and swallowing. The people who were lucky enough not to lose their life were left with a wide range of disabilities ranging from muscle weakness to blurred vision. Allergen, however, countered that their product was “purified, highly diluted and safe and effective” (“Lawsuit targets Botox maker”, 2008).

Finally, in 2009, the FDA decided after a petition from Public Citizen (public advocacy group), that Botox and other similar anti-wrinkle drugs from that point on had to carry a warning label that signals its potential dangers, such as difficulty in breathing and swallowing (“Group Seeks New Warning About Botox”, 2008). They issued a black box warning for all Botox products, which is the strongest safety measure the FDA can issue. Interestingly enough, this warning label is usually issued for medications that have serious life threatening risks. The FDA also decided that the Botox companies had to start sending out letters to doctors that warned them of the risks of Botox and provided a medication guide for patients after their injection (“F.D.A Orders Warning Label for Botox and Similar Drugs”, 2009).

MARKETING

However, there are also other controversies, particularly regarding the marketing of Botox products. In 2010, Dysport launched a new marketing campaign called the “Dysport challenge”, which promised Botox users who were unsatisfied with the Dysport product a rebate on the treatment with Allergan’s Botox. Such marketing campaigns result from the drug companies’ efforts to gain customer loyalty by issuing rebates, discounts and giveaways. This is important especially in the sector of Botox drugs because insurance does not cover such medical treatments. Users need to pay their physicians directly, which makes efforts in marketing of these products so essential. However, these marketing campaigns are strongly criticized because rebates and discounts transform Botox to a consumer product, which should not happen with a medical product that can have severe side effects. It turns doctors who get rebates on certain medical treatments into market sellers. They distribute the product where they receive discounts on to their patients because they can profit from these deals. In effect, they do not look at the safety of the product, but see it more as a consumer product. However, critics believe that medical products such as Botox should not be handled as consumer goods. They are afraid that doctors and patients start to make their decisions concerning Botox based on money instead of safety and efficacy (“To Take on Botox, Rival Tries Rebate”, 2010).

WHO CAN ADMINISTER AND WHERE ONE CAN RECEIVE BOTOX TREATMENTS

The issue in respect to who can offer Botox treatments and where it can be offered has also emerged as a large problem. No federal or state laws prohibit doctors from offering cosmetic procedures as soon as they have state licenses. This means that not only plastic surgeons can offer these services, but so can dentists offer Botox injections after simply taking a weekend course on it. This results in the fact that inexperienced doctors are allowed to treat patients with Botox. This is risky since Botox is increasingly becoming a consumer product where many people only look at price and convenience of the treatment and not at the qualifications and experience of the doctor. Therefore, they put themselves at risk because any medical treatment can be potentially harmful if the person giving them is not properly trained. Thus, critics warn consumers of getting Botox treatments in, for example, malls because these places may be cheap, but do not employ experienced staff (“Having a Little Work Done (at the Mall)”, 2008). In this respect critics again warn of the risks of seeing a Botox treatment merely as a consumer product (“The Little Botox Shop Around the Corner”, 2007).

References

[1] [Allergan, Inc. (2010). BOTOX History and Development-Allergan. Retrieved from: http://www.allergan.com/assets/pdf/botox_history_and_development.pdf. [Accessed on 5/9/2012]]

[2] [Carruthers, Alastair. (2002). Botulinum Toxin Type A: History and Current Cosmetic Use in the upper Face. Disease-a-Month, 48:5, 299-322. Retrieved from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0011502902500602 [Accessed on 5/9/2012].]

[3] [Cote, et al. (2005). Botulinum toxin type A injections: Adverse Events reported to the US Food and Drug Administration in therapeutic and cosmetic cases. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, vol. 53, 3, 407-415. Retrieved from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0190962205019857. [Accessed on 5/9/2012]]

[4] [Girion, L. (2008). Lawsuit targets Botox maker. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved from: http://articles.latimes.com/2008/jul/10/business/fi-botox10 [Accessed on 5/1/12]]

[5] [Harris, G. (2008, January 25). Group Seeks New Warning About Botox. The New York Times. Retrieved from: http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9400E3DC1139F936A15752C0A96E9C8B63&ref=botoxdrug [Accessed on 5/1/12] ] [6] [Helfrich, Y. R., Sachs, D. L., & Voorhees, J. J. (2008). Overview of Skin Aging and Photoaging. Dermatology Nursing, 20:3. 177-183. Retrieved from: http://www.dermatologynursing.net/ceonline/2010/article20177183.pdf]

[8] [Ingraham, John L. (2010). March of the Microbes: Sighting the Unseen. Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University. ]

[9] [Kopera, Daisy. (2011). Botulinum toxin historical aspects: from food poisoning to pharmaceutical. International Journal of Dermatalogy, 50:8, 976-980. Retrieved from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1365-4632.2010.04821.x/pdf [Accessed on 5/9/2012].]

[10] [Mapes, Diane. (2007). Frozen in Time: Botox over the years. MSNBC Retrieved from: http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/21369061/ns/health-skin_and_beauty/t/frozen-time-botox-over-years/#.T6qqY46T-QQ. [Accessed on 5/9/2012]]

[11] [Morrissey, J. (2008). Having a Little Work Done (at the Mall). The New York Times. Retrieved from: http://www.nytimes.com/2008/01/13/business/13sleek.html?ref=botoxdrug [Accessed: 5/1/12]]

[12] [Preidt, Robert. (2012). ‘Off-label’ Drug Use Common but strong evidence is lacking in most cases, Canadian study finds. HealthDay News. Retrieved from: http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/news/fullstory_124134.html. [Accessed on 5/9/2012]]

[13] [U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2011). Medication Guide Botox Botox Cosmetic for Injection. Retrieved from: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DrugSafety/UCM176360.pdf?utm_campaign=Google2&utm_source=fdaSearch&utm_medium=website&utm_term=Botox&utm_content=3 [Accessed on 5/9/2012].]

[14] [Singer, N. (2007). The Little Botox Shop Around the Corner. The New York Times. Retrieved from: http://www.nytimes.com/2007/04/19/fashion/19skin.html?ref=botoxdrug [Accessed on 5/1/12] ]

[15] [Singer, N. (2009). F.D.A Orders Warning Label for Botox and Similar Drugs. The New York Times. Retrieved from: http://www.nytimes.com/2009/05/01/business/01botox.html?_r=1&ref=botoxdrug [Accessed on 5/1/12] ]

[16] [Singer, N. (2010, March 11). To Take on Botox, Rival Tries Rebate. The New York Times. Retrieved from: http://www.nytimes.com/2010/03/12/business/media/12wrinkle.html?_r=2&ref=botoxdrug_ [Accessed on 5/1/12] ]

Edited by Clint Trenkelbach, Rodolfo Edeza, Sabine Carrell students of Rachel Larsen in Bio 083 at Bowdoin College [1]