Shock chlorination: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 12: | Line 12: | ||

===<i>Cryptosporidium</i>=== | ===<i>Cryptosporidium</i>=== | ||

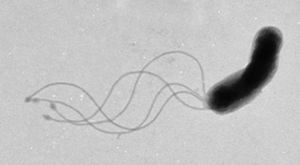

[[Image:Cryptosporidium1.jpeg|thumb|300px|right|Immunofluorescence of <i>Cryptosporidium</i>, the microbe that caused an epidemic in Milwaukee in 1993. Over 104 deaths were credited to the waterborne microbe . Courtesy: [http://www.epa.gov/microbes/cpt_seq1.html H.D.A Lindquist (EPA)]]] | [[Image:Cryptosporidium1.jpeg|thumb|300px|right|Immunofluorescence of <i>Cryptosporidium</i>, the microbe that caused an epidemic in Milwaukee in 1993. Over 104 deaths were credited to the waterborne microbe . Courtesy: [http://www.epa.gov/microbes/cpt_seq1.html H.D.A Lindquist (EPA)]]] | ||

<i>[http://microbewiki.kenyon.edu/index.php/Cryptosporidium Cryptosporidium parvum]</i> is a type of parasite capable of causing gastrointestinal illness. Unlike <i>Helicobacter pylori</i>, however, <i>Cryptosporidium</i> has been proven to be unresponsive to chlorination | <i>[http://microbewiki.kenyon.edu/index.php/Cryptosporidium Cryptosporidium parvum]</i> is a type of parasite capable of causing gastrointestinal illness. Unlike <i>Helicobacter pylori</i>, however, <i>Cryptosporidium</i> has been proven to be unresponsive to chlorination<sup>3</sup>. | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

| Line 31: | Line 31: | ||

<sup>2</sup> [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11529557 Horiuchi T., Ohkusa T., Watanabe M., Kobayashi D., Miwa H., Eishi Y. "''Helicobacter pylori'' DNA in dirnking water in Japan". ''Microbol Immunol''. 2001. Volume 45(7). p. 515-9.] | <sup>2</sup> [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11529557 Horiuchi T., Ohkusa T., Watanabe M., Kobayashi D., Miwa H., Eishi Y. "''Helicobacter pylori'' DNA in dirnking water in Japan". ''Microbol Immunol''. 2001. Volume 45(7). p. 515-9.] | ||

<sup>3</sup>{Korich, D. G., Mead J.R., et al. "Effects of ozone, chlorine dioxide, chlorine, and monochloramine on Cryptosporidium parvum oocyst viability." 1990. Appl Environ Microbiol 56(5). p. 1423-8. | |||

<br>Edited by Erika Jensen, student of [mailto:slonczewski@kenyon.edu Joan Slonczewski] for [http://biology.kenyon.edu/courses/biol116/biol116_Fall_2013.html BIOL 116 Information in Living Systems], 2013, [http://www.kenyon.edu/index.xml Kenyon College]. | <br>Edited by Erika Jensen, student of [mailto:slonczewski@kenyon.edu Joan Slonczewski] for [http://biology.kenyon.edu/courses/biol116/biol116_Fall_2013.html BIOL 116 Information in Living Systems], 2013, [http://www.kenyon.edu/index.xml Kenyon College]. | ||

<!--Do not edit or remove this line-->[[Category:Pages edited by students of Joan Slonczewski at Kenyon College]] | <!--Do not edit or remove this line-->[[Category:Pages edited by students of Joan Slonczewski at Kenyon College]] | ||

Revision as of 16:24, 5 November 2013

Introduction

From swimming pools to wells, chlorine is a common chemical used to disinfect water sources.

Microbial agents

Helicobacter pylori

Helicobacter pylori is known to cause gastritis and peptic ulcers.

Studies done in Peru1 and Japan2 have shown the presence of the bacteria in public water sources, proving its possibility as a waterborne microbe.

Cryptosporidium

Cryptosporidium parvum is a type of parasite capable of causing gastrointestinal illness. Unlike Helicobacter pylori, however, Cryptosporidium has been proven to be unresponsive to chlorination3.

Methods

Commercial

Domestic

Success rates

Alternative methods

Scientists are not content with shock chlorination. As technology advances, methods to improve both testing and disinfection are created.

References

3{Korich, D. G., Mead J.R., et al. "Effects of ozone, chlorine dioxide, chlorine, and monochloramine on Cryptosporidium parvum oocyst viability." 1990. Appl Environ Microbiol 56(5). p. 1423-8.

Edited by Erika Jensen, student of Joan Slonczewski for BIOL 116 Information in Living Systems, 2013, Kenyon College.