Rickettsia conorii: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 44: | Line 44: | ||

Based upon the antigenicity of their lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and the differences in the diseases that they cause, members are divided into two groups, the spotted fever group (SFG) and the typhus group (TG) (Vishwanath, 1991). Both groups have been classified by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) as `select agents' for bioterrorism (http://www2.niaid.nih.gov/biodefense/bandc_priority.htm). | Based upon the antigenicity of their lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and the differences in the diseases that they cause, members are divided into two groups, the spotted fever group (SFG) and the typhus group (TG) (Vishwanath, 1991). Both groups have been classified by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) as `select agents' for bioterrorism (http://www2.niaid.nih.gov/biodefense/bandc_priority.htm). | ||

==Pathology== | |||

Below are tables of different groups of ''Ricketsia'' along with the diseases that each species cause and their general geological distribution. From [http://www.med.sc.edu:85/mayer/ricketsia.htm The University of South Carolina.] | |||

<font size="+1">Spotted Fever Group </font> | |||

{| width="794" border="1" | |||

| '''Organism''' | |||

| '''Disease''' | |||

| '''Distribution''' | |||

|- | |||

| width="206" | ''R. rickettsii '' | |||

| width="218" | Rocky Mountain spotted fever | |||

| width="345" | Western hemisphere | |||

|- | |||

| ''R. akari'' | |||

| Rickettsialpox | |||

| USA, former Soviet Union | |||

|- | |||

| ''R. conorii '' | |||

| Boutonneuse fever | |||

| Mediterranean countries, Africa, India, Southwest Asia | |||

|- | |||

| ''R. sibirica '' | |||

| Siberian tick typhus | |||

| Siberia, Mongolia, nothern China | |||

|- | |||

| ''R. australis '' | |||

| Australian tick typhus | |||

| Australia | |||

|- | |||

| ''R. japonica '' | |||

| Oriental spotted fever | |||

| Japan | |||

|} | |||

<font size="+1">Typhus Group </font> | |||

{| width="790" border="1" | |||

| '''Organism''' | |||

| '''Disease''' | |||

| '''Distribution''' | |||

|- | |||

| width="206" | ''R. prowazekii '' | |||

| width="222" | | |||

Epidemic typhus<br /> Recrudescent typhus<br /> Sporadic typhus | |||

| width="340" | South America and Africa<br /> Worldwide<br /> United States | |||

|- | |||

| ''R. typhi'' | |||

| Murine typhus | |||

| Worldwide | |||

|} | |||

<font size="+1">Scrub typhus group </font> | |||

{| width="792" border="1" | |||

| '''Organism''' | |||

| '''Disease''' | |||

| '''Distribution''' | |||

|- | |||

| width="206" | ''R. tsutsugamushi '' | |||

| width="224" | Scrub typhus | |||

| width="339" | Asia, northern Australia, Pacific Islands | |||

|} | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

Revision as of 07:42, 3 May 2007

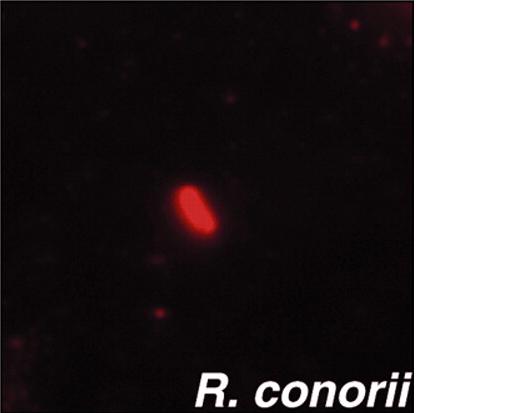

A Microbial Biorealm page on the genus Rickettsia conorii

Classification

Higher order taxa:

Bacteria ; Proteobacteria ; Alphaproteobacteria ; Rickettsiales ; Rickettsiaceae ; Rickettsieae ; Rickettsia ; spotted fever group ; Rickettsia conorii

Gene Classification based on COG functional categories

Species:

Orientia tsutsugamushi;

spotted fever group: Candidatus R. principis; Israeli tick typhus rickettsia; R. aeschimannii; R. africae; R. akari; R. amblyommii; R. andeana; R. australis; R. conorii; R. cooleyi; R. felis; R. heilongjiangensis; R. heilongjiangii; R. helvtica; R. honei; R. hulinensis; R. hulinii; R. japonica; R. martinet; R. massiliae; R. monacensis; R. montanensis; R. moreli; R. parkeri; R. peacockii; R. rhipicephali; R. rickettsii; R. sibirica subgroup; R. slovaca; R. sp.

Typhus group: R. canadensis; R. prowazekii; R. typhi

Unclassified Rickettsia: Candidatus R. tarasevichiae; R. bellii; R. publicis; R. sp.

|

NCBI: Taxonomy Genome: -R. conorii str. Malish 7 -R. prowazekii str. Madrid E |

Description and Significance

Rickettsia bacteria are well known pathogens. Rickettsia conorii have been described as the causative agents of Mediterranean spotted fever, Astrakhan fever, Israeli spotted fever, and Indian tick typhus in the Mediterranean basin and Africa, Southern Russia, Middle East, and India, respectively. These rickettsioses are transmitted to humans by Rhipicephalus ticks [1]. Furthermore, most of their clinical features overlap and are characterized by a febrile illness and a generalized maculopapular rash. However, an inoculation eschar is seldom present in Astrakhan fever and Israeli spotted fever but common in Mediterranean spotted fever and is contracted by contact with infected brown dog ticks.

Genome Structure

The genome of Rickettsia conorii is 1,268,755 base pairs in length and contains 1374 protein-coding genes.There are no genes for anaerobic glycolysis and also the biosynthesis and regulation of amino acids and nucleosides in free-living bacteria.Rickettsia are obligate intracellular small gram-negative proteobacteria of the -subdivision associated with different arthropod hosts. The genomes of Rickettsia as well as the mitochondria are small, highly derived, "products of several types of reductive evolution" (Andersson et al. 1998). The comparison of the R. conorii genome sequence with its close relative Rickettsia prowazekii revealed a new type of "coding" mobile element (Rickettsia-specific palindromic element, RPE) frequently found inserted in frame within open reading frames (ORFs), whereas all previously described bacterial palindromic repeats appeared exclusively located within noncoding regions. We identified 656 interspersed repeated sequences classified into 10 distinct families. Of the 10 families, three palindromic sequence families showed clear cases of insertions into open reading frames (ORFs). The location of those in-frame insertions appears to be always compatible with the encoded protein three-dimensional (3-D) fold and function.

Cell Structure and Metabolism

Subsequent to adherence, rickettsiae, like some other pathogenic bacteria, enter into non-phagocytic host cells and then quickly lyse the phagocytic vacuole (Hackstadt, 1996). Within the cytoplasm, rickettsiae begin to divide and in some cases are able to polymerize host actin filaments to propel themselves intra- and intercellularly (Gouin et al., 2004; Gouin et al., 1999; Heinzen et al., 1993; Teysseire et al., 1992).

Interactions of TG and SFG rickettsiae with various cultured cells show that internalization is associated with a phospholipase A2 activity and host actin polymerization (Silverman et al., 1992; Walker et al., 2001; Walker, 1984). However, little more is known about the interactions between SFG rickettsiae and cultured cells, in particular the mechanism(s) by which R. conorii invades non-phagocytic cells. An initial investigation of proteins that could control actin dynamics during R. conorii invasion revealed that the Arp2/3 complex is recruited to the entry site. We then utilized various approaches to disrupt signaling pathways that have been previously demonstrated to activate the Arp2/3 complex directly or indirectly. We found that R. conorii uses pathways involving Cdc42, PI 3-kinase, c-Src and other PTK activities to enter non-phagocytic cells and that signals from these pathways may be coordinated to ultimately activate the Arp2/3 complex.

Ecology

Subsequent proliferation of SFG rickettsiae at the site of inoculation, typically in endothelial cells, results in the characteristic dermal and epidermal necrosis known as `eschar' or `tache noire' (Walker et al., 1988). Injury to the vascular endothelium leads to an increase in vascular permeability and leakage of fluid into the interstitial space, resulting in the characteristic dermal rash (Hand et al., 1970; Walker et al., 1988). Bacteria can then spread via lymphatic vessels to the lymph nodes and via the bloodstream to various other tissues including the lungs, spleen, liver, kidneys and heart (Walker and Gear, 1985).

Based upon the antigenicity of their lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and the differences in the diseases that they cause, members are divided into two groups, the spotted fever group (SFG) and the typhus group (TG) (Vishwanath, 1991). Both groups have been classified by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) as `select agents' for bioterrorism (http://www2.niaid.nih.gov/biodefense/bandc_priority.htm).

Pathology

Below are tables of different groups of Ricketsia along with the diseases that each species cause and their general geological distribution. From The University of South Carolina.

Spotted Fever Group

| Organism | Disease | Distribution |

| R. rickettsii | Rocky Mountain spotted fever | Western hemisphere |

| R. akari | Rickettsialpox | USA, former Soviet Union |

| R. conorii | Boutonneuse fever | Mediterranean countries, Africa, India, Southwest Asia |

| R. sibirica | Siberian tick typhus | Siberia, Mongolia, nothern China |

| R. australis | Australian tick typhus | Australia |

| R. japonica | Oriental spotted fever | Japan |

Typhus Group

| Organism | Disease | Distribution |

| R. prowazekii |

Epidemic typhus |

South America and Africa Worldwide United States |

| R. typhi | Murine typhus | Worldwide |

Scrub typhus group

| Organism | Disease | Distribution |

| R. tsutsugamushi | Scrub typhus | Asia, northern Australia, Pacific Islands |

References

General:

- Yong Zhu, Pierre-Edouard Fournier, Marina Eremeeva, and Didier Raoult1. 2004. "Proposal to create subspecies of Rickettsia conorii based on multi-locus sequence typing and an emended description of Rickettsia conorii." Biomed Central.

- Reinert, Birgit. 2001. "Insights into genome evolution: The sequence of Rickettsia conorii." Genome News Network

- Chantal Abergel, Guillaume Blanc, Vincent Monchois, Patricia Renesto, Cécile Sigoillot, Hiroyuki Ogata, Didier Raoult and Jean-Michel Claverie. 2006. "Impact of the Excision of an Ancient Repeat Insertion on Rickettsia conorii Guanylate Kinase Activity ." Oxford Journals.

- Andersson, Siv G. E., Alireza Zomorodipour, Jan O. Andersson, Thomas Sicheritz-Ponten, U. Cecilia M. Alsmark, Raf M. Podowski, A. Kristina Naslund, Ann-Sofie Eriksson, Herbert H. Winkler, and Charles G. Kurland. 1998. "The genome sequence of Rickettsia prowazekii and the origin of mitochondria." Nature, vol. 396. Macmillan Publishers Ltd. (133-143)

- Walker, D. H. and Gear, J. H. (1985). Correlation of the distribution of Rickettsia conorii, microscopic lesions, and clinical features in South African tick bite fever. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 34, 361-371.[Medline]

Cell Structure and Metabolism

- Juan J. Martinez and Pascale Cossart. 2004. "Early signaling events involved in the entry of Rickettsia conorii into mammalian cells."Journal of Cell Science 117, 5097-5106

- Silverman, D. J., Santucci, L. A., Meyers, N. and Sekeyova, Z. (1992). Penetration of host cells by Rickettsia rickettsii appears to be mediated by a phospholipase of rickettsial origin. Infect. Immun. 60, 2733-2740.[Abstract/Free Full Text]

- Hackstadt, T. (1996). The biology of rickettsiae. Infect. Agents Dis. 5, 127-143.[Medline]

- Gouin, E., Egile, C., Dehoux, P., Villiers, V., Adams, J., Gertler, F., Li, R. and Cossart, P. (2004). The RickA protein of Rickettsia conorii activates the Arp2/3 complex. Nature 427, 457-461.[CrossRef][Medline]

Edited by Cindy Zhang,student of Rachel Larsen and Kit Pogliano