Roseobacter denitrificans: Difference between revisions

Slonczewski (talk | contribs) |

|||

| (20 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Uncurated}} | |||

{{Biorealm Genus}} | {{Biorealm Genus}} | ||

| Line 38: | Line 39: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

The genome sequence of ''Roseobacter denitrificans'' sp OCh 114 was completed in 2006 by a team in Arizona State University as the first AAP sequenced. (12) ''R. denitrificans'' contains a circular chromosome of 4,133,097 bp and four plasmids. Nearly half of the genes in the largest plasmid (pTB1) share a high degree of similarity to genes in plasmid pSD25 from ''Ruegeria'' sp. isolate PR1b and the Ti plasmid from ''Agrobacterium tumefaciens'' strain C58. (8) The conservation of many DNA integration and transfer proteins, plasmid replication proteins, and inverted repeats imply that R. denitrificans plasmid pTB1 may also promote lateral gene transfer. This possibility is especially interesting considering the propensity of R. denitrificans to associate with higher organisms. The genome of ''R. denitrificans'' additionally lacks genes that code for known photosynthetic carbon fixation pathways, with most notably missing the genes for Calvin cycle enzymes ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase (RuBisCO) and phosphoribukolkinase. (2) | The genome sequence of ''Roseobacter denitrificans'' sp OCh 114 was completed in 2006 by a team in Arizona State University as the first AAP sequenced. (12) ''R. denitrificans'' contains a circular chromosome of 4,133,097 bp and four plasmids. Nearly half of the genes in the largest plasmid (pTB1) share a high degree of similarity to genes in plasmid pSD25 from ''Ruegeria'' sp. isolate PR1b and the Ti plasmid from ''Agrobacterium tumefaciens'' strain C58. (8) The conservation of many DNA integration and transfer proteins, plasmid replication proteins, and inverted repeats imply that ''R. denitrificans'' plasmid pTB1 may also promote lateral gene transfer. This possibility is especially interesting considering the propensity of ''R. denitrificans'' to associate with higher organisms. The genome of ''R. denitrificans'' additionally lacks genes that code for known photosynthetic carbon fixation pathways, with most notably missing the genes for Calvin cycle enzymes ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase (RuBisCO) and phosphoribukolkinase. (2) | ||

Nearly 15% of the ''R. denitrificans'' genome is dedicated to the construction of transport proteins. Among these transporters are more than 120 genes coding for peptide and amino acid transporters(many branched chain), more than 110 genes coding | Nearly 15% of the ''R. denitrificans'' genome is dedicated to the construction of transport proteins. Among these transporters are more than 120 genes coding for peptide and amino acid transporters(many branched chain), more than 110 genes coding | ||

| Line 60: | Line 61: | ||

The bacteria are gram-negative rods motile by means of polar or subpolar flagella, oxidase positive, and catalase positive, and produce a small amount of acids from glucose, fructose, xylose, and the other carbohydrates. As an AAP the bacteria captures light in order to gain energy and grow. The primary photosynthetic pigment of AAPBs is bacteriochlorophyll a. The amount of bacteriochlorophyll a found in Och 114 was 5.5 nmol/mg (dry weight). (13) This cellular bacteriochlorophyll a content is rather low, and the genes coding the enzymes synthesizing bacteriochlorophyll a may not be phenotype-expressed when limited by environmental conditions. (6) Although bacteriochlorophyll a is possesed thus the organism is capable of aerobic photosynthesis; however, it is still unable to grow autotrophically. (14) | The bacteria are gram-negative rods motile by means of polar or subpolar flagella, oxidase positive, and catalase positive, and produce a small amount of acids from glucose, fructose, xylose, and the other carbohydrates. As an AAP the bacteria captures light in order to gain energy and grow. As one of the nine ''Roseobacter'' species that are motile, ''R. denitrificans'' is unique by being the only one able to move without forming rosettes. (17) The primary photosynthetic pigment of AAPBs is bacteriochlorophyll a. The amount of bacteriochlorophyll a found in Och 114 was 5.5 nmol/mg (dry weight). (13) This cellular bacteriochlorophyll a content is rather low, and the genes coding the enzymes synthesizing bacteriochlorophyll a may not be phenotype-expressed when limited by environmental conditions. (6) Although bacteriochlorophyll a is possesed thus the organism is capable of aerobic photosynthesis; however, it is still unable to grow autotrophically. (14) | ||

''R.denitrificans'' does not rely light energy as the only source for energy though and utilizes many other energy-yielding metabolic pathways that likely | ''R. denitrificans'' does not rely light energy as the only source for energy though and utilizes many other energy-yielding metabolic pathways that likely help provide additional energy, in the form of ATP, for the formation of OAA from CO2 and metabolic intermediates. The organism has a broad range of physiological properties and uses a multitude of different carbon sources. Additional energy is gained by the organisms through oxidization of reduced sulfur compounds such as sulfite or thiosulfate. (13,14) Inorganic sulfur oxidation, encoded by the large soxWXYZABCDEF cluster, is a likely source for extra energy production yielding sulfate as environmental output. (2) Additionally ''R. denitrificans'' has the ability to process organic phosphates as well as degrade the chemically stable C-P bond-containing phosphonates (despite the fact that a major limiting growth factors in the open ocean is phosphorous availability). Another factor is that the organism lacks N2O reductase thus unable to fix dinitrogen. Yet the reduction of oxidized nitrogen compounds is a significant aspect of the lifestyle of the bacteria. The diversity and adaptibility of ''R. denitrificans'' is demonstrated by the other means it acquires nitrogen other than through dinitrogen, and it has a large complement of genes to account for this. (2) | ||

All other aerobic organisms that oxidize CO to CO2 for energy grow autotrophically using the Calvin cycle. Although ''R. denitrificans'' has not been shown to oxidize CO in culture, it contains the necessary genes (coxG and coxSML) and has been suggested to likely perform the reaction under proper conditions. (15) | All other aerobic organisms that oxidize CO to CO2 for energy grow autotrophically using the Calvin cycle. Although ''R. denitrificans'' has not been shown to oxidize CO in culture, it contains the necessary genes (coxG and coxSML) and has been suggested to likely perform the reaction under proper conditions. (15) | ||

==Ecology== | ==Ecology== | ||

The genomes of ''Roseobacter'' reflect a dynamic environment and diverse interactions with marine plankton. Comparative genome sequence analysis of the bacteria suggest that cellular requirements for nitrogen are largely provided by regenerated ammonium and organic compounds (polyamines, allophanate, and urea), while typical sources of carbon include amino acids, glyoxylate, and aromatic metabolites. An unexpectedly large number of genes are predicted to encode proteins involved in the production, degradation, and efflux of toxins and metabolites. | |||

A mechanism likely involved in cell-to-cell DNA or protein transfer was also discovered: vir-related genes encoding a type IV secretion system typical of bacterial pathogens, suggesting a potential for interacting with neighboring cells and impacting the routing of organic matter into the microbial loop. Genes include those for carbon monoxide oxidation, dimethylsulfoniopropionate demethylation, and aromatic compound degradation. Genes shared with other cultured marine bacteria include those for utilizing sodium gradients, transport and metabolism of sulfate, and osmoregulation. (18) | |||

Members of the ''Roseobacter'' lineage play an important role for the global carbon and sulfur cycle and the climate, since they have the trait of aerobic anoxygenic photosynthesis, oxidize the greenhouse gas carbon monoxide, and produce the climate-relevant gas dimethylsulfide through the degradation of algal osmolytes. Production of bioactive metabolites and quorum-sensing-regulated control of gene expression mediate their success in complex communities. (9) | |||

==Pathology== | ==Pathology== | ||

There are no known pathological effects of this bacterium on humans. | There are no known pathological effects of this bacterium species on humans. | ||

==Application to Biotechnology== | ==Application to Biotechnology== | ||

The study of microbial oxidation or reduction of elements is of great importance for our understanding of biogeochemical cycling of these elements in nature. Many transformations of metals in anaerobic and aerobic environments are the result of the direct enzymatic activity of bacteria. Bacterial bioremediation is a potentially attractive and ecologically sound method of removing environmental contaminants such as in polluted industrial wastewaters. (5) | |||

Support for AAP's larger influence in the global carbon cycle (including that of ''R. denitrificans'') is growing as evidence exists that the bacteria are abundant in the upper open ocean and comprise at least 11% of the total microbial community. The aerobic phototropic bacterium is a member of a group of a group of organisms that dominate the microbial biota of the surface of the oceans and other surface waters and thus likely plays a major role in the way the earth absorbs and releases carbon dioxide. They act as aerobic photoheterotrophs, metabolizing organic carbon when available, but capable of photosynthetic light utilization when organic carbon is scarce. They are globally distributed in the euphotic zone and represent an unrecognized component of the marine microbial community that appears to be critical to the cycling of both organic and inorganic carbon in the ocean. (6) | |||

Key transformations for the biogeochemical cycling of sulfur that involve both organic and inorganic compounds have also been identified in ''Roseobacter'' clade members as well as having pathways that may play a role in determining the balance between the incorporation of sulfur into the marine microbial food web (the demethylation/demethiolation pathway) and the release of sulfur in the form of the climate-influencing gas dimethyl sulfide (the cleavage pathway). Inorganic sulfur oxidation is an important process in many coastal and benthic marine environments (e.g., sediments and sulfide-rich habitats), and the recent discovery of genes encoding sulfur oxidation enzymes (sox genes) in open ocean bacterioplankton suggests a previously unrecognized role for sulfur oxidation in these systems as well. (19, 20) | |||

==Current Research== | ==Current Research== | ||

''Mixotrophic fixation of CO2'' | ''Mixotrophic fixation of CO2'' | ||

| Line 84: | Line 93: | ||

Recent studies suggest that due to genes missing for Calvin cycle enzymes in ''R. denitrificans'' while retaining genes needed for processes similar to plant C4 sequestration, crassulacean acid metabolism, and anaplerotic carbon fixation, coupled with photoheterotrophic energy metabolism, a mixotrophic fixation is a more likely fit than an autotrophic one for the organism. Analysis of the completed genome sequence also reveals the depth the bacteria's ability to adapt to changing conditions and its numerous mechanisms evolved for chemotrophic and phototrophic energy metabolism, influencing its wide dispersal in the biosphere and contribution to the global carbon cycle. (2) | Recent studies suggest that due to genes missing for Calvin cycle enzymes in ''R. denitrificans'' while retaining genes needed for processes similar to plant C4 sequestration, crassulacean acid metabolism, and anaplerotic carbon fixation, coupled with photoheterotrophic energy metabolism, a mixotrophic fixation is a more likely fit than an autotrophic one for the organism. Analysis of the completed genome sequence also reveals the depth the bacteria's ability to adapt to changing conditions and its numerous mechanisms evolved for chemotrophic and phototrophic energy metabolism, influencing its wide dispersal in the biosphere and contribution to the global carbon cycle. (2) | ||

'' | ''Binuclear centerCu-containing NO reductase homologue'' | ||

Spectroscopic analyses was performed on the nitric oxide reductase (NOR) homologue from ''R. denitrificans''. It was suggested that this enzyme has some intriguing properties in the binuclear site. The frequencies of ν(Fe–CO) and ν(C–O) are close to those of cytochrome aa3- and bo3-type oxidases in spite of the similarity with NOR in the primary structure. It has been generally accepted that heme–copper oxidases evolved from NOR, and during evolution, non-heme iron would have been replaced by copper. The NOR homologue may have evolved from NOR by the same replacement of the non-heme metal, which might have brought structural features similar to those of oxygen-reducing enzymes in the catalytic site. Heme b at the binuclear site is suggested to be in a six-coordinate low-spin state in the reduced form. This is peculiar to this enzyme in the heme–copper oxidase superfamily, and may cause the low molecular activity of the NOR homologue. (16) | |||

''Influence of culture conditions of Production of Antibacterial Compounds and Biofilm Formation'' | |||

The phenotypes for the production of antibacterial compounds, rosette formation, attachment ability, and biofilm formation were detected in several Roseobacter strains. Culture conditions were found to influence both antibacterial activity and bacterial attachment and biofilm formation, as these phenotypes were expressed under almost only static culture conditions. The degree to which the organisms grew as rosettes is linked to attachment and biofilm formation. Collectively, these phenotypes may facilitate the colonization of dinoflagellates, algae, and marine particles by Roseobacter clade bacteria. The ability to produce antibacterial compounds that principally inhibit non-Roseobacter species, combined with an enhancement in biofilm formation, may give members of the Roseobacter clade a selective advantage and help to explain the dominance of members of this clade in association with marine algal microbiota. (17) | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| Line 105: | Line 120: | ||

8) [http://jb.asm.org/cgi/ijlink?linkType=ABST&journalCode=sci&resid=294/5550/2323 Goodner, B., G. Hinkle, S. Gattung, N. Miller, M. Blanchard, B. Qurollo, B. S. Goldman, Y. Cao, M. Askenazi, C. Halling, L. Mullin, K. Houmiel, J. Gordon, M. Vaudin, O. Iartchouk, A. Epp, F. Liu, C. Wollam, M. Allinger, D. Doughty, C. Scott, C. Lappas, B. Markelz, C. Flanagan, C. Crowell, J. Gurson, C. Lomo, C. Sear, G. Strub, C. Cielo, and S. Slater. 2001. Genome sequence of the plant pathogen and biotechnology agent Agrobacterium tumefaciens C58. Science 294:2323-2328] | 8) [http://jb.asm.org/cgi/ijlink?linkType=ABST&journalCode=sci&resid=294/5550/2323 Goodner, B., G. Hinkle, S. Gattung, N. Miller, M. Blanchard, B. Qurollo, B. S. Goldman, Y. Cao, M. Askenazi, C. Halling, L. Mullin, K. Houmiel, J. Gordon, M. Vaudin, O. Iartchouk, A. Epp, F. Liu, C. Wollam, M. Allinger, D. Doughty, C. Scott, C. Lappas, B. Markelz, C. Flanagan, C. Crowell, J. Gurson, C. Lomo, C. Sear, G. Strub, C. Cielo, and S. Slater. 2001. Genome sequence of the plant pathogen and biotechnology agent Agrobacterium tumefaciens C58. Science 294:2323-2328] | ||

9) [http:// | 9) [http://arjournals.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev.micro.60.080805.142115?cookieSet=1&journalCode=micro I. Hagner-Döbler and H. Biebl. 2006. Environmental Biology of the Marine Roseobacter Lineage Annual Review of Microbiology Vol. 60: 255-280] | ||

10) http://www.roseobase.org/roseo/och114.html | 10) http://www.roseobase.org/roseo/och114.html | ||

| Line 119: | Line 134: | ||

15) King, G. M. (2003) Molecular and culture-based analyses of aerobic carbon monoxide oxidizer diversity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:7257-7265 | 15) King, G. M. (2003) Molecular and culture-based analyses of aerobic carbon monoxide oxidizer diversity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:7257-7265 | ||

16) [http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0005272804000192 Y. Matsuda, T. Uchida, H. Hori, T. Kitagawa, H. Arata - Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Bioenergetics, 2004] | |||

17) [http://aem.asm.org/cgi/content/full/73/2/442 JB Bruhn, L Gram, R Belas (2007) Production of Antibacterial Compounds and Biofilm Formation by Roseobacter Species Are Influenced by Culture Conditions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.] | |||

18) [http://aem.asm.org/cgi/content/abstract/73/14/4559 M. A. Moran, R. Belas, M. A. Schell, J. M. González, F. Sun, S. Sun, B. J. Binder, J. Edmonds, W. Ye, B. Orcutt, E. C. Howard, C. Meile, W. Palefsky, A. Goesmann, Q. Ren, I. Paulsen, L. E. Ulrich, L. S. Thompson, E. Saunders, and A. Buchan (2007) Ecological Genomics of Marine Roseobacters. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, Vol. 73, No. 14, p. 4559-4569] | |||

19) [http://aem.asm.org/cgi/external_ref?access_num=10.1038/nature03170&link_type=DOI Moran, M. A., A. Buchan, J. M. González, J. F. Heidelberg, W. B. Whitman, R. P. Kiene, J. R. Henriksen, G. M. King, R. Belas, C. Fuqua, L. Brinkac, M. Lewis, S. Johri, B. Weaver, G. Pai, J. A. Eisen, E. Rahe, W. M. Sheldon, W. Ye, T. R. Miller, J. Carlton, D. A. Rasko, I. T. Paulsen, Q. Ren, S. C. Daugherty, R. T. Deboy, R. J. Dodson, A. S. Durkin, R. Madupu, W. C. Nelson, S. A. Sullivan, M. J. Rosovitz, D. H. Haft, J. Selengut, and N. Ward. 2004. Genome sequence of Silicibacter pomeroyi reveals adaptations to the marine environment. Nature 432:910-913.] | |||

20) [http://aem.asm.org/cgi/ijlink?linkType=FULL&journalCode=aem&resid=68/12/5804 Yoch, D. C. 2002. Dimethylsulfoniopropionate: its sources, role in the marine food web, and biological degradation to dimethylsulfide. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:5804-5815] | |||

Edited by George Huang student of [mailto:ralarsen@ucsd.edu Rachel Larsen] | Edited by George Huang student of [mailto:ralarsen@ucsd.edu Rachel Larsen] | ||

Edited by KLB | |||

Latest revision as of 18:33, 31 July 2014

A Microbial Biorealm page on the genus Roseobacter denitrificans

Classification

Higher order taxa

Bacteria, Proteobacteria, Alphaproteobacteria, Rhodobacterales, Rhodobacteraceae, Roseobacter

Species

Roseobacter denitrificans sp. OCh114 (previously called Erythrobacter sp. OCh114)

Description and significance

Roseobacter denitrificans is a purple aerobic anyoxygenic phototrophic (AAP) bacterium that dwells free-living in lakes and ocean surface waters, soils and even near deep sea hydrothermal vents. (1,5) It can be isolated from the surfaces of green seaweeds of the coastal marine sediments in Australia, using proteinase K treatment followed by phenol extraction. (10,2) The first instance of its isolation however, was from the samples collected in aerobic marine environments: thalli of Enteromorpha linza, Porphyra sp., Sargussum horneri; beach sand; and the surface seawater from Aburatsubo Inlet in March and May 1978. (13) Members of the Roseobacter clade are widespread and abundant in such marine environments, having diverse metabolisms. The purple proteobacteria in particular, are the only known organisms to capture light energy to enhance growth requiring the presence of oxygen yet do not produce oxygen themselves. It grows photoautotrophically only at low oxygen levels, while at higher oxygen levels, the photosynthetic apparatus is down-regulated, resulting in chemotrophic growth using organic carbon. (2) The highly adaptive AAPs compose more than 10% of the microbial community in some euphotic upper ocean waters and are potentially major contributors to the fixation of the greenhouse gas CO2. The marine AAP species R. denitrificans grows not only photoheterotrophically in the presence of oxygen and light but also anaerobically in the dark using nitrate or trimethylamine N-oxide as an electron acceptor. It is the most studied AAP for this reason and is one of the main model organisms to study aerobic phototrophic bacteria. (2)

The importances of the bacterium's genome sequence are for the following reasons: 1) The evolutionary genesis of photosynthesis genes - it is a marine bacterium, and so may be representative of the globally huge population of aerobic phototrophic bacteria and help narrow their true evolutionary position by whole genome comparisons; (4,7) 2) Pathways of carbon dioxide fixation and production - in understanding the processes for its autotrophic CO2 production and the key genes involved in AAP CO2 fixation pathways. As the only aerobic phototrophic bacterium capable of anaerobic growth with use of nitrate as a terminal electron acceptor, it can also be used to facilitate subsequent studies of the effects of oxygen on photosynthetic and other metabolic processes; (5,6) 3) Light and oxygen signal transduction in gene expression - offering an opportunity, through bioinformatic approaches, to use the AAP's exaggerated responses to study of both light- and oxygen-responsive pathways and mechanisms that are difficult to study in other species. (3,4,11)

Genome structure

The genome sequence of Roseobacter denitrificans sp OCh 114 was completed in 2006 by a team in Arizona State University as the first AAP sequenced. (12) R. denitrificans contains a circular chromosome of 4,133,097 bp and four plasmids. Nearly half of the genes in the largest plasmid (pTB1) share a high degree of similarity to genes in plasmid pSD25 from Ruegeria sp. isolate PR1b and the Ti plasmid from Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain C58. (8) The conservation of many DNA integration and transfer proteins, plasmid replication proteins, and inverted repeats imply that R. denitrificans plasmid pTB1 may also promote lateral gene transfer. This possibility is especially interesting considering the propensity of R. denitrificans to associate with higher organisms. The genome of R. denitrificans additionally lacks genes that code for known photosynthetic carbon fixation pathways, with most notably missing the genes for Calvin cycle enzymes ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase (RuBisCO) and phosphoribukolkinase. (2)

Nearly 15% of the R. denitrificans genome is dedicated to the construction of transport proteins. Among these transporters are more than 120 genes coding for peptide and amino acid transporters(many branched chain), more than 110 genes coding for sugar and carbohydrate transporters, and more than 70 cation and iron transporters. These help the bacteria to acquire nitrogen other than fixing dinitrogen and allow it to adapt to the uptake of a variety of available carbon sources. (2)

The Complete Genome Sequence of Roseobacter denitrificans Reveals a Mixotrophic Rather than Photosynthetic Metabolism provides a possible explanation of how CO2 is fixated and produced using the complete genome sequence. "Based on the genome sequence of R. denitrificans, we suggest that they fix CO2 mixotrophically by using a sequestration pathway supplemented with additional CO2 provided by CO oxidation and heterotrophic respiration." (2)

Cell structure and metabolism

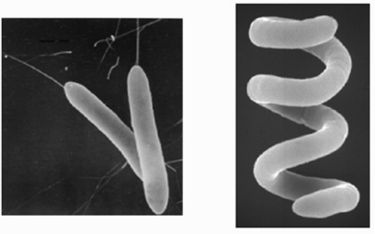

The bacteria are gram-negative rods motile by means of polar or subpolar flagella, oxidase positive, and catalase positive, and produce a small amount of acids from glucose, fructose, xylose, and the other carbohydrates. As an AAP the bacteria captures light in order to gain energy and grow. As one of the nine Roseobacter species that are motile, R. denitrificans is unique by being the only one able to move without forming rosettes. (17) The primary photosynthetic pigment of AAPBs is bacteriochlorophyll a. The amount of bacteriochlorophyll a found in Och 114 was 5.5 nmol/mg (dry weight). (13) This cellular bacteriochlorophyll a content is rather low, and the genes coding the enzymes synthesizing bacteriochlorophyll a may not be phenotype-expressed when limited by environmental conditions. (6) Although bacteriochlorophyll a is possesed thus the organism is capable of aerobic photosynthesis; however, it is still unable to grow autotrophically. (14)

R. denitrificans does not rely light energy as the only source for energy though and utilizes many other energy-yielding metabolic pathways that likely help provide additional energy, in the form of ATP, for the formation of OAA from CO2 and metabolic intermediates. The organism has a broad range of physiological properties and uses a multitude of different carbon sources. Additional energy is gained by the organisms through oxidization of reduced sulfur compounds such as sulfite or thiosulfate. (13,14) Inorganic sulfur oxidation, encoded by the large soxWXYZABCDEF cluster, is a likely source for extra energy production yielding sulfate as environmental output. (2) Additionally R. denitrificans has the ability to process organic phosphates as well as degrade the chemically stable C-P bond-containing phosphonates (despite the fact that a major limiting growth factors in the open ocean is phosphorous availability). Another factor is that the organism lacks N2O reductase thus unable to fix dinitrogen. Yet the reduction of oxidized nitrogen compounds is a significant aspect of the lifestyle of the bacteria. The diversity and adaptibility of R. denitrificans is demonstrated by the other means it acquires nitrogen other than through dinitrogen, and it has a large complement of genes to account for this. (2)

All other aerobic organisms that oxidize CO to CO2 for energy grow autotrophically using the Calvin cycle. Although R. denitrificans has not been shown to oxidize CO in culture, it contains the necessary genes (coxG and coxSML) and has been suggested to likely perform the reaction under proper conditions. (15)

Ecology

The genomes of Roseobacter reflect a dynamic environment and diverse interactions with marine plankton. Comparative genome sequence analysis of the bacteria suggest that cellular requirements for nitrogen are largely provided by regenerated ammonium and organic compounds (polyamines, allophanate, and urea), while typical sources of carbon include amino acids, glyoxylate, and aromatic metabolites. An unexpectedly large number of genes are predicted to encode proteins involved in the production, degradation, and efflux of toxins and metabolites.

A mechanism likely involved in cell-to-cell DNA or protein transfer was also discovered: vir-related genes encoding a type IV secretion system typical of bacterial pathogens, suggesting a potential for interacting with neighboring cells and impacting the routing of organic matter into the microbial loop. Genes include those for carbon monoxide oxidation, dimethylsulfoniopropionate demethylation, and aromatic compound degradation. Genes shared with other cultured marine bacteria include those for utilizing sodium gradients, transport and metabolism of sulfate, and osmoregulation. (18)

Members of the Roseobacter lineage play an important role for the global carbon and sulfur cycle and the climate, since they have the trait of aerobic anoxygenic photosynthesis, oxidize the greenhouse gas carbon monoxide, and produce the climate-relevant gas dimethylsulfide through the degradation of algal osmolytes. Production of bioactive metabolites and quorum-sensing-regulated control of gene expression mediate their success in complex communities. (9)

Pathology

There are no known pathological effects of this bacterium species on humans.

Application to Biotechnology

The study of microbial oxidation or reduction of elements is of great importance for our understanding of biogeochemical cycling of these elements in nature. Many transformations of metals in anaerobic and aerobic environments are the result of the direct enzymatic activity of bacteria. Bacterial bioremediation is a potentially attractive and ecologically sound method of removing environmental contaminants such as in polluted industrial wastewaters. (5)

Support for AAP's larger influence in the global carbon cycle (including that of R. denitrificans) is growing as evidence exists that the bacteria are abundant in the upper open ocean and comprise at least 11% of the total microbial community. The aerobic phototropic bacterium is a member of a group of a group of organisms that dominate the microbial biota of the surface of the oceans and other surface waters and thus likely plays a major role in the way the earth absorbs and releases carbon dioxide. They act as aerobic photoheterotrophs, metabolizing organic carbon when available, but capable of photosynthetic light utilization when organic carbon is scarce. They are globally distributed in the euphotic zone and represent an unrecognized component of the marine microbial community that appears to be critical to the cycling of both organic and inorganic carbon in the ocean. (6)

Key transformations for the biogeochemical cycling of sulfur that involve both organic and inorganic compounds have also been identified in Roseobacter clade members as well as having pathways that may play a role in determining the balance between the incorporation of sulfur into the marine microbial food web (the demethylation/demethiolation pathway) and the release of sulfur in the form of the climate-influencing gas dimethyl sulfide (the cleavage pathway). Inorganic sulfur oxidation is an important process in many coastal and benthic marine environments (e.g., sediments and sulfide-rich habitats), and the recent discovery of genes encoding sulfur oxidation enzymes (sox genes) in open ocean bacterioplankton suggests a previously unrecognized role for sulfur oxidation in these systems as well. (19, 20)

Current Research

Mixotrophic fixation of CO2

Recent studies suggest that due to genes missing for Calvin cycle enzymes in R. denitrificans while retaining genes needed for processes similar to plant C4 sequestration, crassulacean acid metabolism, and anaplerotic carbon fixation, coupled with photoheterotrophic energy metabolism, a mixotrophic fixation is a more likely fit than an autotrophic one for the organism. Analysis of the completed genome sequence also reveals the depth the bacteria's ability to adapt to changing conditions and its numerous mechanisms evolved for chemotrophic and phototrophic energy metabolism, influencing its wide dispersal in the biosphere and contribution to the global carbon cycle. (2)

Binuclear centerCu-containing NO reductase homologue

Spectroscopic analyses was performed on the nitric oxide reductase (NOR) homologue from R. denitrificans. It was suggested that this enzyme has some intriguing properties in the binuclear site. The frequencies of ν(Fe–CO) and ν(C–O) are close to those of cytochrome aa3- and bo3-type oxidases in spite of the similarity with NOR in the primary structure. It has been generally accepted that heme–copper oxidases evolved from NOR, and during evolution, non-heme iron would have been replaced by copper. The NOR homologue may have evolved from NOR by the same replacement of the non-heme metal, which might have brought structural features similar to those of oxygen-reducing enzymes in the catalytic site. Heme b at the binuclear site is suggested to be in a six-coordinate low-spin state in the reduced form. This is peculiar to this enzyme in the heme–copper oxidase superfamily, and may cause the low molecular activity of the NOR homologue. (16)

Influence of culture conditions of Production of Antibacterial Compounds and Biofilm Formation

The phenotypes for the production of antibacterial compounds, rosette formation, attachment ability, and biofilm formation were detected in several Roseobacter strains. Culture conditions were found to influence both antibacterial activity and bacterial attachment and biofilm formation, as these phenotypes were expressed under almost only static culture conditions. The degree to which the organisms grew as rosettes is linked to attachment and biofilm formation. Collectively, these phenotypes may facilitate the colonization of dinoflagellates, algae, and marine particles by Roseobacter clade bacteria. The ability to produce antibacterial compounds that principally inhibit non-Roseobacter species, combined with an enhancement in biofilm formation, may give members of the Roseobacter clade a selective advantage and help to explain the dominance of members of this clade in association with marine algal microbiota. (17)

References

1) Fleischman D and Kramer D (1998) Photosynthetic rhizobia. Biochim Biophys Acta 1364: 17-36.

10) http://www.roseobase.org/roseo/och114.html

11) http://genomes.tgen.org/rhodobacter.html

14) Sorokin, DY (1995) Sulfitobacter pontiacus gen. nov., sp. nov.—a new heterotrophic bacterium from the Black-Sea, specialized on sulfite oxidation. Microbiology 64: 295–305

15) King, G. M. (2003) Molecular and culture-based analyses of aerobic carbon monoxide oxidizer diversity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:7257-7265

Edited by George Huang student of Rachel Larsen

Edited by KLB