Tospovirus: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| (21 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Curated}} | |||

{{Viral Biorealm Family}} | {{Viral Biorealm Family}} | ||

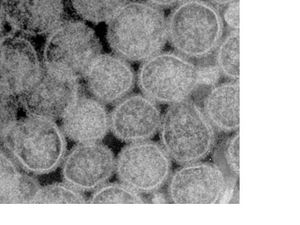

<br> | <br> [[Image:005-nvir.jpg|thumb|Tospovirus particles (from HIK site)]] | ||

==Baltimore Classification== | ==Baltimore Classification== | ||

<br> Group V (negative sense ssRNA) | <br> Group V (negative sense ssRNA) | ||

==Higher | ==Higher Order Categories== | ||

<br> Family ''Bunyaviridae'' | <br> Family ''Bunyaviridae''<br> Genus ''Tospovirus'' | ||

==Species== | ==Species== | ||

<br> Tomato spotted wilt virus (TSWV); Impatiens necrotic spot virus (INSV); Watermelon silver mottle virus (WSMoV) | <br> Tomato spotted wilt virus (TSWV); Impatiens necrotic spot virus (INSV); Watermelon silver mottle virus (WSMoV); many others | ||

==Description and Significance== | ==Description and Significance== | ||

<br> Tospoviruses are enveloped viruses that infect plants, leading to tissue necrosis. The first tospovirus, the tomato spotted wilt virus, was isolated in Australia in 1915 (Adkins et.al., 2005). An extremely wide variety of plants are susceptible to tospoviruses | <br> Tospoviruses are enveloped viruses that infect plants, leading to tissue necrosis. The first tospovirus, the tomato spotted wilt virus, was isolated in Australia in 1915 (Adkins et.al., 2005). An extremely wide variety of plants are susceptible to tospoviruses (including crops such as tomatoes, watermelon, lettuce, and groundnuts, and flowers such as irises, impatiens, lilies, and orchids), and the geographic host range of topsviruses encompasses nearly every major agricultural area on the globe (Jones, 2005). Tospoviruses rank among the ten most detrimental plant viruses worldwide, and the recent resurgence of the virus and spread into novel hosts has sparked concern among agriculturalists and horticulturists (Prins & Goldbach, 1998). | ||

==Genome Structure== | ==Genome Structure== | ||

<br> The tospovirus genome consists of three ssRNA molecules, known as a tripartite RNA genome (Cortez et.al., 2001). The RNA molecules are simply known as L (Large), M (Medium), and S (Small). The entire genome codes for six proteins via five different open reading frames (ORFs). The L RNA | <br> The tospovirus genome consists of three ssRNA molecules, known as a tripartite RNA genome (Cortez et.al., 2001). The RNA molecules are simply known as L (Large), M (Medium), and S (Small). The entire genome codes for six proteins via five different open reading frames (ORFs). <br><br> The L RNA: RNA-dependent RNA polymerase for viral replication and genome transcription <br> The M RNA: two envelope precursor glycoproteins (G1 & G2) and the viral movement protein (NSm) for cell-to-cell viral transfer <br> The S RNA: the nucleoprotein (N) used to construct the virion capsid and a non-structural protein (NSs) of unknown function <br><br> The M and S RNAs are special, in that both are ambisense, meaning that one gene is encoded in the negative sense sequence and another gene is encoded in the positive sense sequence (Cortez et.al., 2001). The RNA molecules are also capable of forming pseudo-circular panhandle structures, as well as stable hairpins, due to the presence of complementary terminal sequences (Dong et.al., 2008). | ||

==Virion Structure of a Tospovirus== | ==Virion Structure of a Tospovirus== | ||

<br> The tospovirus virion consists of a quasi-spherical capsid particle 80-120 nm in diameter containing 10-20 copies of the ssRNA genome (Adkins et.al., 2005). The mature particle is usually enclosed in a lipid envelope formed by budding from the host's Golgi (Prins & Goldbach, 1998). | <br> The tospovirus virion consists of a quasi-spherical capsid particle 80-120 nm in diameter containing 10-20 copies of the ssRNA genome (Adkins et.al., 2005). The mature particle is usually enclosed in a lipid envelope, which is formed by budding from the host's Golgi and incorporating the viral envelope glycoproteins (Prins & Goldbach, 1998). | ||

==Reproductive Cycle of a Tospovirus in a Host Cell== | ==Reproductive Cycle of a Tospovirus in a Host Cell== | ||

<br> Tospovirus enters the cell via an insect vector. The virus sheds its capsid, and the viral RNA polymerase is produced using host cell machinery. Subsequent RNA polymerase activity depends on a chemical cue similar to quorum sensing. At low concentrations of the virus nucleocapsid protein (eg. at initial entry), the RNA polymerase makes mRNAs that encode the other viral proteins necessary for packaging and transport. The host cell machinery is then used to translate the viral proteins. At high concentrations of | <br> Tospovirus enters the cell via an insect vector. The virus sheds its capsid, and the viral RNA polymerase is produced using host cell machinery. Subsequent RNA polymerase activity depends on a chemical cue similar to quorum sensing. At low concentrations of the virus nucleocapsid N protein (eg. at initial entry), the RNA polymerase makes mRNAs that encode the other viral proteins necessary for packaging and transport. The host cell machinery is then used to translate the viral proteins. At high concentrations of N protein (eg. after translation of the viral proteins has occurred), the RNA polymerase can begin replicating the viral genome. After virion packaging occurs, viral transmission can proceed in two ways. The virus can be transmitted directly to another host cell (without an envelope) via the viral movement protein (NSm) or indirectly (as a mature, enveloped particle) via uptake by an insect vector (Prins & Goldbach, 1998). | ||

==Viral Ecology & Pathology== | ==Viral Ecology & Pathology== | ||

<br> The tospovirus insect vector is the thrip, a small, winged herbivore. Thrips can infect a plant by transferring virus particles during feeding. In other instances, thrips can ingest the virus and shed particles as waste (Jones, 2005). Common insect vectors include the ''Thrips'' and ''Frankliniella'' species. | <br> The tospovirus insect vector is the thrip, a small, winged herbivore. Thrips can infect a plant by transferring virus particles during feeding. In other instances, thrips can ingest the virus and shed particles as waste (Jones, 2005). Common insect vectors include the ''Thrips'' and ''Frankliniella'' species. [[Image:427722822.jpg|thumb|Tomato spotted wilt virus (Adkins et.al., 2005)]] | ||

Upon infection, the virus induces tissue necrosis resulting in spots and streaks on leaves and discolored rings and spots on fruits (EPPO, 2004). Symptoms may vary, depending on factors such as cultivation method, age of the plant, nutritional and environmental conditions, and the virus species and/or serotype (EPPO, 2004). Current research is focused on methods for virus diagnosis and prevention, as the tospovirus host range is wide and includes several economically important crops and ornamental plants (EPPO, 2004). The most common methods of prevention include the use of special mulches and insecticide to control thrip feeding and prevent plant-to-plant spread of the virus. The construction of transgenic plants containing resistant RNA (specially designed for particular tospovirus species like certain strains of TSWV) has also shown some promise (Adkins et.al., 2005). | Upon infection, the virus induces tissue necrosis resulting in spots and streaks on leaves and discolored rings and spots on fruits (EPPO, 2004). Symptoms may vary, depending on factors such as cultivation method, age of the plant, nutritional and environmental conditions, and the virus species and/or serotype (EPPO, 2004). Current research is focused on methods for virus diagnosis and prevention, as the tospovirus host range is wide and includes several economically important crops and ornamental plants (EPPO, 2004). The virus must be diagnosed using molecular techniques such as genome comparison and ELISA assays (Adkins et.al., 2005). The most common methods of prevention include the use of special mulches and insecticide to control thrip feeding and prevent plant-to-plant spread of the virus. The construction of transgenic plants containing resistant RNA (specially designed for particular tospovirus species like certain strains of TSWV) has also shown some promise (Adkins et.al., 2005). | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

Adkins, S, T. Zitter, & T. Momol. "Tospoviruses (Family ''Bunyaviridae'', Genus ''Tospovirus'')." Univ. of Florida IFAS (Institute of Food & Agricultural Science) fact sheet PP-212 (2005). | Adkins, S, T. Zitter, & T. Momol. "Tospoviruses (Family ''Bunyaviridae'', Genus ''Tospovirus'')." Univ. of Florida IFAS (Institute of Food & Agricultural Science) fact sheet PP-212 (2005). http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/PP134 | ||

Cortez, I., J. Saaijer, K.S. Wongjkaew, A.M. Pereira, R. Goldbach, D. Peters, & R. Kormelink. "Identification and characterization of a novel tospovirus species using a new RT-PCR approach." ''Archives of Virology'' 146 (2001): 265-278. | Cortez, I., J. Saaijer, K.S. Wongjkaew, A.M. Pereira, R. Goldbach, D. Peters, & R. Kormelink. "Identification and characterization of a novel tospovirus species using a new RT-PCR approach." ''Archives of Virology'' 146 (2001): 265-278. | ||

| Line 37: | Line 38: | ||

EPPO (Eur. & Mediterranean Plant Protection Org.) "Tomato spotted wilt tospovirus, Impatiens necrotic spot tospovirus and Watermelon silver mottle tospovirus." ''EPPO Bulletin'' 34 (2004): 271-279. | EPPO (Eur. & Mediterranean Plant Protection Org.) "Tomato spotted wilt tospovirus, Impatiens necrotic spot tospovirus and Watermelon silver mottle tospovirus." ''EPPO Bulletin'' 34 (2004): 271-279. | ||

HIK. http://www.hik.hu/.../site/books/b133/ch03s02.html | |||

Jones, D.R. "Plant viruses transmitted by thrips." ''European Journal of Plant Pathology'' 113 (2005): 119-157. | Jones, D.R. "Plant viruses transmitted by thrips." ''European Journal of Plant Pathology'' 113 (2005): 119-157. | ||

| Line 42: | Line 45: | ||

Prins, M. & R. Goldbach. "The emerging problem of tospovirus infection and nonconventional methods of control." ''Trends in Microbiology'' 31(6) (1998). | Prins, M. & R. Goldbach. "The emerging problem of tospovirus infection and nonconventional methods of control." ''Trends in Microbiology'' 31(6) (1998). | ||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

Page authored for [http://biology.kenyon.edu/courses/biol375/biol375syl08.htm BIOL 375 Virology], September 2008 | Page authored by Sasha Minium '09 for [http://biology.kenyon.edu/courses/biol375/biol375syl08.htm BIOL 375 Virology], September 2008 | ||

<!--Do not edit or remove this line-->[[Category:Pages edited by students of Joan Slonczewski at Kenyon College]] | |||

Latest revision as of 00:43, 8 August 2010

A Viral Biorealm page on the family Tospovirus

Baltimore Classification

Group V (negative sense ssRNA)

Higher Order Categories

Family Bunyaviridae

Genus Tospovirus

Species

Tomato spotted wilt virus (TSWV); Impatiens necrotic spot virus (INSV); Watermelon silver mottle virus (WSMoV); many others

Description and Significance

Tospoviruses are enveloped viruses that infect plants, leading to tissue necrosis. The first tospovirus, the tomato spotted wilt virus, was isolated in Australia in 1915 (Adkins et.al., 2005). An extremely wide variety of plants are susceptible to tospoviruses (including crops such as tomatoes, watermelon, lettuce, and groundnuts, and flowers such as irises, impatiens, lilies, and orchids), and the geographic host range of topsviruses encompasses nearly every major agricultural area on the globe (Jones, 2005). Tospoviruses rank among the ten most detrimental plant viruses worldwide, and the recent resurgence of the virus and spread into novel hosts has sparked concern among agriculturalists and horticulturists (Prins & Goldbach, 1998).

Genome Structure

The tospovirus genome consists of three ssRNA molecules, known as a tripartite RNA genome (Cortez et.al., 2001). The RNA molecules are simply known as L (Large), M (Medium), and S (Small). The entire genome codes for six proteins via five different open reading frames (ORFs).

The L RNA: RNA-dependent RNA polymerase for viral replication and genome transcription

The M RNA: two envelope precursor glycoproteins (G1 & G2) and the viral movement protein (NSm) for cell-to-cell viral transfer

The S RNA: the nucleoprotein (N) used to construct the virion capsid and a non-structural protein (NSs) of unknown function

The M and S RNAs are special, in that both are ambisense, meaning that one gene is encoded in the negative sense sequence and another gene is encoded in the positive sense sequence (Cortez et.al., 2001). The RNA molecules are also capable of forming pseudo-circular panhandle structures, as well as stable hairpins, due to the presence of complementary terminal sequences (Dong et.al., 2008).

Virion Structure of a Tospovirus

The tospovirus virion consists of a quasi-spherical capsid particle 80-120 nm in diameter containing 10-20 copies of the ssRNA genome (Adkins et.al., 2005). The mature particle is usually enclosed in a lipid envelope, which is formed by budding from the host's Golgi and incorporating the viral envelope glycoproteins (Prins & Goldbach, 1998).

Reproductive Cycle of a Tospovirus in a Host Cell

Tospovirus enters the cell via an insect vector. The virus sheds its capsid, and the viral RNA polymerase is produced using host cell machinery. Subsequent RNA polymerase activity depends on a chemical cue similar to quorum sensing. At low concentrations of the virus nucleocapsid N protein (eg. at initial entry), the RNA polymerase makes mRNAs that encode the other viral proteins necessary for packaging and transport. The host cell machinery is then used to translate the viral proteins. At high concentrations of N protein (eg. after translation of the viral proteins has occurred), the RNA polymerase can begin replicating the viral genome. After virion packaging occurs, viral transmission can proceed in two ways. The virus can be transmitted directly to another host cell (without an envelope) via the viral movement protein (NSm) or indirectly (as a mature, enveloped particle) via uptake by an insect vector (Prins & Goldbach, 1998).

Viral Ecology & Pathology

The tospovirus insect vector is the thrip, a small, winged herbivore. Thrips can infect a plant by transferring virus particles during feeding. In other instances, thrips can ingest the virus and shed particles as waste (Jones, 2005). Common insect vectors include the Thrips and Frankliniella species.

Upon infection, the virus induces tissue necrosis resulting in spots and streaks on leaves and discolored rings and spots on fruits (EPPO, 2004). Symptoms may vary, depending on factors such as cultivation method, age of the plant, nutritional and environmental conditions, and the virus species and/or serotype (EPPO, 2004). Current research is focused on methods for virus diagnosis and prevention, as the tospovirus host range is wide and includes several economically important crops and ornamental plants (EPPO, 2004). The virus must be diagnosed using molecular techniques such as genome comparison and ELISA assays (Adkins et.al., 2005). The most common methods of prevention include the use of special mulches and insecticide to control thrip feeding and prevent plant-to-plant spread of the virus. The construction of transgenic plants containing resistant RNA (specially designed for particular tospovirus species like certain strains of TSWV) has also shown some promise (Adkins et.al., 2005).

References

Adkins, S, T. Zitter, & T. Momol. "Tospoviruses (Family Bunyaviridae, Genus Tospovirus)." Univ. of Florida IFAS (Institute of Food & Agricultural Science) fact sheet PP-212 (2005). http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/PP134

Cortez, I., J. Saaijer, K.S. Wongjkaew, A.M. Pereira, R. Goldbach, D. Peters, & R. Kormelink. "Identification and characterization of a novel tospovirus species using a new RT-PCR approach." Archives of Virology 146 (2001): 265-278.

Dong, J.H., X.F. Cheng, Y.Y. Yin, Q. Fang, M. Ding, T.T. Li, L.Z. Zhang, X.X. Su, & Z.K. Zhang. "Characterization of tomato zonate spot virus, a new tospovirus in China." Archives of Virology" 153 (2008): 855-864.

EPPO (Eur. & Mediterranean Plant Protection Org.) "Tomato spotted wilt tospovirus, Impatiens necrotic spot tospovirus and Watermelon silver mottle tospovirus." EPPO Bulletin 34 (2004): 271-279.

HIK. http://www.hik.hu/.../site/books/b133/ch03s02.html

Jones, D.R. "Plant viruses transmitted by thrips." European Journal of Plant Pathology 113 (2005): 119-157.

Prins, M. & R. Goldbach. "The emerging problem of tospovirus infection and nonconventional methods of control." Trends in Microbiology 31(6) (1998).

Page authored by Sasha Minium '09 for BIOL 375 Virology, September 2008