Catenulispora acidiphila: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (17 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{ | {{Moore2012}} | ||

==Classification== | ==Classification== | ||

| Line 8: | Line 7: | ||

===Species=== | ===Species=== | ||

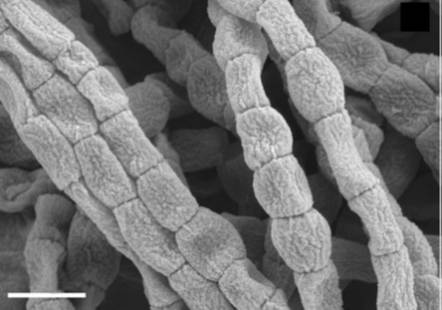

[[Image: | [[Image:Cylindrical_arthrospores_of_Catenulispora_acidiphila_are_shown_above.jpg |frame|right|150px|Scanning electron Micrograph of cylindrical arthrospores in <I>Catenulispora acidiphila</I> are shown above (1). Bar, 1 μm.]] | ||

''Catenulispora acidiphila'' | ''Catenulispora acidiphila'' | ||

==Description and significance== | ==Description and significance== | ||

The Actinobacteria phylum is known to include freshwater life, marine life and some common soil life. | The Actinobacteria phylum is known to include freshwater life, marine life and some common soil life. Members of this phylum are important in the decomposition of organic material and carbon cycle, which puts nutrients back into the environment. Actinobacteria are also of high pharmacological interest because they can produce secondary metabolites (3). <I>C. acidiphila</I> is known only to be found in soil in Gerenzano, Italy. <I>C. acidiphila</I> forms aerial and vegetative mycelia (2). Since it’s part of the class Actinobacteria and the order Actinomycetales, it may produce novel metabolites or be an antibiotic producer. However, no information on the production of novel metabolites is currently known (1). | ||

==Genome structure== | ==Genome structure== | ||

The complete genome of C. acidiphila was sequenced and published in 2009; this was the first complete genome sequenced of the Actinobacterial family Catenulisporaceae. The genome is 10,467,782 bp in length and comprises one circular chromosome. The content of the G-C in DNA is 69.8% of the total number of genes. Of the 9122 predicted genes, 99.28% were protein coding genes and just 0.76% of the genes were classified as RNA genes (2). For more information about the known functions of this genome, see tables 3 and 4 in the following article: “Complete genome sequence of Catenulispora acidiphila type strain” (2). | The complete genome of <I>C. acidiphila</I> was sequenced and published in 2009; this was the first complete genome sequenced of the Actinobacterial family Catenulisporaceae. The genome is 10,467,782 bp in length and comprises one circular chromosome. The content of the G-C in DNA is 69.8% of the total number of genes. Of the 9122 predicted genes, 99.28% were protein coding genes and just 0.76% of the genes were classified as RNA genes (2). For more information about the known functions of this genome, see tables 3 and 4 in the following article: “Complete genome sequence of <I>Catenulispora acidiphila</I> type strain” (2). | ||

==Cell and colony structure== | ==Cell and colony structure== | ||

Catenulispora genus consists of Gram-positive, non-motile and non-acid fast colonies of the organism that form branching hyphae. Vegetative mycelium are non-fragmentary and the aerial hyphae start to septate into chains of arthrospores (a resting sporelike cell produced by some bacteria) that are cylindrical. In C. acidiphila the spores have an average diameter of about 0.5 µm and are also known to range in length from 0.4-1 µm (1). | Catenulispora genus consists of Gram-positive, non-motile and non-acid fast colonies of the organism that form branching hyphae. Vegetative mycelium are non-fragmentary and the aerial hyphae start to septate into chains of arthrospores (a resting sporelike cell produced by some bacteria) that are cylindrical. In <I>C. acidiphila</I> the spores have an average diameter of about 0.5 µm and are also known to range in length from 0.4-1 µm (1). | ||

==Metabolism== | ==Metabolism== | ||

C. acidiphila is an aerobic species, but is also capable of non-pigmented and reduced growth under anaerobic and microaerophilic conditions. It has the ability to hydrolyze starch and casein. It can also use carbon sources as a source of energy. The sources of carbon that this species can use are the following: glucose, fructose, glycerol, mannitol, xylose and arabinose. C. acidiphila can’t reduce nitrates. Hydrogen sulfide ( | <I>C. acidiphila</I> is an aerobic species, but is also capable of non-pigmented and reduced growth under anaerobic and microaerophilic conditions. It has the ability to hydrolyze starch and casein. It can also use carbon sources as a source of energy. The sources of carbon that this species can use are the following: glucose, fructose, glycerol, mannitol, xylose and arabinose. <I>C. acidiphila</I> can’t reduce nitrates. Hydrogen sulfide (H<sub>2</sub>S) is also produced by this species (1, 2). The strain of <I>C. acidiphila</I> was also resistant to lysozyme, which wasn’t reported for the Catenulispora genus (2). The mechanism of how it reduces hydrogen sulfide is not known at this time. | ||

==Ecology== | ==Ecology== | ||

C. acidiphila is an acidophilic species that grows well in the pH range of 4.3-6.8, but optimally at a pH of 6.0. They can grow optimally at a temperature of between 22-28 | <I>C. acidiphila</I> is an acidophilic species that grows well in the pH range of 4.3-6.8, but optimally at a pH of 6.0. They can grow optimally at a temperature of between 22-28 °C; however, it can grow significantly between 11-37 °C. As of right now, <I>C. acidiphila</I> has only been found in Geranzano, Italy. (1). | ||

==Pathology== | ==Pathology== | ||

As of right now, C. acidiphila is not known to cause any infections or diseases. However, some species of the Actinobacteria are known to form a wide variety of secondary metabolites. Since a wide variety of secondary metabolites are a source of potent antibiotics, the Streptomyces species has been the main organism targeted by the pharmaceutical industry (3). Since C. acidiphila is part of the Actinobacteria phylum, it could possibly be targeted by the pharmaceutical industry (2). | As of right now, <I>C. acidiphila</I> is not known to cause any infections or diseases. However, some species of the Actinobacteria are known to form a wide variety of secondary metabolites. Since a wide variety of secondary metabolites are a source of potent antibiotics, the Streptomyces species has been the main organism targeted by the pharmaceutical industry (3). Since <I>C. acidiphila</I> is part of the Actinobacteria phylum, it could possibly be targeted by the pharmaceutical industry (2). | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

[1] Busti, E, et al. "Catenulispora Acidiphila Gen. Nov., Sp. Nov., a Novel, Mycelium-forming Actinomycete, and Proposal of Catenulisporaceae Fam. Nov." International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology (2006) 56: 1741-746. DOI: 10.1099/ijs.0.63858-0 | [1] Busti, E, et al. "<I>Catenulispora Acidiphila</I> Gen. Nov., Sp. Nov., a Novel, Mycelium-forming Actinomycete, and Proposal of Catenulisporaceae Fam. Nov." International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology (2006) 56: 1741-746. DOI: 10.1099/ijs.0.63858-0 | ||

[2] Copeland, Alex, Alla Lapidus, Tijana Glavina, et al. "Complete Genome Sequence of Catenulispora Acidiphila Type Strain (ID 139908T)." Standards in Genomic Sciences (2009) 1: 119-125 DOI:10.4056/sigs.17259 | [2] Copeland, Alex, Alla Lapidus, Tijana Glavina, et al. "Complete Genome Sequence of <I>Catenulispora Acidiphila</I> Type Strain (ID 139908T)." Standards in Genomic Sciences (2009) 1: 119-125 DOI:10.4056/sigs.17259 | ||

[3] Ventura, Marco, et al. “Genomics of Actinobacteria: Tracing the Evolutionary History of an Ancient Phylum.” Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2007 September; 71(3): 495–548. DOI: 10.1128/MMBR.00005-07 | [3] Ventura, Marco, et al. “Genomics of Actinobacteria: Tracing the Evolutionary History of an Ancient Phylum.” Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2007 September; 71(3): 495–548. DOI: 10.1128/MMBR.00005-07 | ||

| Line 40: | Line 39: | ||

Edited by Dustin J Ambrose of University of Southern Maine | Edited by Dustin J Ambrose, student of Dr. Lisa R. Moore, University of Southern Maine | ||

Latest revision as of 15:17, 22 February 2016

Classification

Higher order taxa

Domain (Bacteria); Phylum (Actinobacteria); Class (Actinobacteria); Order (Actinomycetales); Suborder (Catenulisporineae); Family (Catenulisporaceae); Genus (Catenulispora)

Species

Catenulispora acidiphila

Description and significance

The Actinobacteria phylum is known to include freshwater life, marine life and some common soil life. Members of this phylum are important in the decomposition of organic material and carbon cycle, which puts nutrients back into the environment. Actinobacteria are also of high pharmacological interest because they can produce secondary metabolites (3). C. acidiphila is known only to be found in soil in Gerenzano, Italy. C. acidiphila forms aerial and vegetative mycelia (2). Since it’s part of the class Actinobacteria and the order Actinomycetales, it may produce novel metabolites or be an antibiotic producer. However, no information on the production of novel metabolites is currently known (1).

Genome structure

The complete genome of C. acidiphila was sequenced and published in 2009; this was the first complete genome sequenced of the Actinobacterial family Catenulisporaceae. The genome is 10,467,782 bp in length and comprises one circular chromosome. The content of the G-C in DNA is 69.8% of the total number of genes. Of the 9122 predicted genes, 99.28% were protein coding genes and just 0.76% of the genes were classified as RNA genes (2). For more information about the known functions of this genome, see tables 3 and 4 in the following article: “Complete genome sequence of Catenulispora acidiphila type strain” (2).

Cell and colony structure

Catenulispora genus consists of Gram-positive, non-motile and non-acid fast colonies of the organism that form branching hyphae. Vegetative mycelium are non-fragmentary and the aerial hyphae start to septate into chains of arthrospores (a resting sporelike cell produced by some bacteria) that are cylindrical. In C. acidiphila the spores have an average diameter of about 0.5 µm and are also known to range in length from 0.4-1 µm (1).

Metabolism

C. acidiphila is an aerobic species, but is also capable of non-pigmented and reduced growth under anaerobic and microaerophilic conditions. It has the ability to hydrolyze starch and casein. It can also use carbon sources as a source of energy. The sources of carbon that this species can use are the following: glucose, fructose, glycerol, mannitol, xylose and arabinose. C. acidiphila can’t reduce nitrates. Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) is also produced by this species (1, 2). The strain of C. acidiphila was also resistant to lysozyme, which wasn’t reported for the Catenulispora genus (2). The mechanism of how it reduces hydrogen sulfide is not known at this time.

Ecology

C. acidiphila is an acidophilic species that grows well in the pH range of 4.3-6.8, but optimally at a pH of 6.0. They can grow optimally at a temperature of between 22-28 °C; however, it can grow significantly between 11-37 °C. As of right now, C. acidiphila has only been found in Geranzano, Italy. (1).

Pathology

As of right now, C. acidiphila is not known to cause any infections or diseases. However, some species of the Actinobacteria are known to form a wide variety of secondary metabolites. Since a wide variety of secondary metabolites are a source of potent antibiotics, the Streptomyces species has been the main organism targeted by the pharmaceutical industry (3). Since C. acidiphila is part of the Actinobacteria phylum, it could possibly be targeted by the pharmaceutical industry (2).

References

[1] Busti, E, et al. "Catenulispora Acidiphila Gen. Nov., Sp. Nov., a Novel, Mycelium-forming Actinomycete, and Proposal of Catenulisporaceae Fam. Nov." International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology (2006) 56: 1741-746. DOI: 10.1099/ijs.0.63858-0

[2] Copeland, Alex, Alla Lapidus, Tijana Glavina, et al. "Complete Genome Sequence of Catenulispora Acidiphila Type Strain (ID 139908T)." Standards in Genomic Sciences (2009) 1: 119-125 DOI:10.4056/sigs.17259

[3] Ventura, Marco, et al. “Genomics of Actinobacteria: Tracing the Evolutionary History of an Ancient Phylum.” Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2007 September; 71(3): 495–548. DOI: 10.1128/MMBR.00005-07

Edited by Dustin J Ambrose, student of Dr. Lisa R. Moore, University of Southern Maine