Drug Resistance in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

==Intrinsic Drug Resistance== | ==Intrinsic Drug Resistance== | ||

<i>M. tuberculosis</i> possess a multitude of resistance mechanisms against a wide range of antibiotics, as far as its intrinsic mechanisms they can be divided into two categories: passive and specialized resistance. [[#References|[ | <i>M. tuberculosis</i> possess a multitude of resistance mechanisms against a wide range of antibiotics, as far as its intrinsic mechanisms (as opposed to acquired mechanisms that are brought about by chromosomal [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mutation mutations], as discussed below) they can be divided into two categories: passive and specialized resistance. [[#References|[]]] | ||

===Passive Resistance=== | ===Passive Resistance Mechanisms=== | ||

• Impermeable cell wall | |||

o Figure 1A. Schematic depiction of the structure of the mycobacterial cell wall. [[#References|[6]]] | |||

o Hydrophobic chemicals unable to enter due to layer of hydrophilic [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arabinogalactan arabinogalactan] [[#References|[6]]] | |||

Wrapped in hydrophobic [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mycolic_acid mycolic acids] to limit entrance of hydrophilic molecules | |||

• Added to arabinogalactan in cell wall by group of mycolyltransferase enzymes | |||

o One gene that encodes one of the mycolytransferases is the FbpA gene | |||

• Shown to be a strong connection between mycolic acid content and antibiotic resistance [[#References|[6]]] | |||

o Figure 1B. <i>fbp</i>A mutants display sensitivity to a broad range of antibiotics | |||

o Despite being considered [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gram-positive_bacteria Gram-positive], Mycobacterium cell wall layers create space that resembles the [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Periplasm periplasm] of [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gram-negative_bacteria Gram-negative bacteria]. [[#References|[6]]] | |||

o Another piece of evidence supporting the impermeability of the Mycobacterial cell wall is the fact that the time it takes for [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/%CE%92-lactam_antibiotic β-lactams] to diffuse through the cell wall takes a hundred times longer than it does for <i>Escherichia coli</i>. [[#References|[7]]] | |||

===Specialized Resistance Mechanisms=== | |||

• Modification and degradation of drugs | |||

• Modification of drug targets | |||

• Efflux pumps | |||

o Figure 2. | |||

[[Image: zac9991016910001.jpg|thumb|upright|right||<br><b>Figure 2. </b> Bactericidal effects of β-lactams on Wild Type and efflux pump KO mutant <i>M. tuberculosis</i> strains over 7 days. Dashed line indicated number of cells at the start of the experiment. Source: [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3623302/ Dinesh N, Sharma S, Balganesh M. Involvement of Efflux Pumps in the Resistance to Peptidoglycan Synthesis Inhibitors in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2013;57(4):1941-1943. doi:10.1128/AAC.01957-12.]]] | |||

[[having trouble getting image|thumb|upright|left|<br><b>Figure 1. </b> A. Schematic depiction of the structure of the mycobacterial cell wall B. <i>fbp</i>A mutants display sensitivity to a broad range of antibiotics, sensitivity indicated by inhibition zone around discs containing same amount of antibiotics (clear zones) Source: [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=Mycobacterial+subversion+of+chemotherapeutic+reagents+and+host+defense+tactics%3A+challenges+in+tuberculosis+drug+development. Nguyen L and Pieters J, 2009]]] | |||

| Line 38: | Line 55: | ||

==Further Reading== | ==Further Reading== | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

Revision as of 17:33, 24 March 2015

Tuberculosis (TB) is a potentially deadly disease caused by pathogenic bacteria, usually Mycobacterium tuberculosis. It has existed in humans since ancient times and had high mortality rates without adequate treatment options before the invention of antibiotics , specifically streptomycin in 1943, that were potent enough to kill the bacteria. [6] In the 1960’s, following a drastic reduction in TB rates around the world, people began to predict that the disease could be completely eradicated within a century. [5] However, this goal proved overly-optimistic as drug-resistant strains had begun to emerge since the first use of antibiotics to treat TB. At first this was mainly due to only using a single drug, streptomycin, to treat the infection, prompting the use of multi-drug therapy but in recent decades multi-drug resistant (MDR), extensively- drug resistant (XDR), and totally-drug resistant (TDR) strains of TB have emerged. [1] Many of these strains are effectively incurable, especially the XDR and TDR strains, even for patients with access to an array of anti-TB drugs. [1] Given their grave public health threat it is crucial to study the molecular biology of the intrinsic and acquired mechanisms of resistance in M. tuberculosis in order to develop new drugs that avoid these mechanisms.

Intrinsic Drug Resistance

M. tuberculosis possess a multitude of resistance mechanisms against a wide range of antibiotics, as far as its intrinsic mechanisms (as opposed to acquired mechanisms that are brought about by chromosomal mutations, as discussed below) they can be divided into two categories: passive and specialized resistance. []

Passive Resistance Mechanisms

• Impermeable cell wall o Figure 1A. Schematic depiction of the structure of the mycobacterial cell wall. [6] o Hydrophobic chemicals unable to enter due to layer of hydrophilic arabinogalactan [6] Wrapped in hydrophobic mycolic acids to limit entrance of hydrophilic molecules • Added to arabinogalactan in cell wall by group of mycolyltransferase enzymes o One gene that encodes one of the mycolytransferases is the FbpA gene • Shown to be a strong connection between mycolic acid content and antibiotic resistance [6] o Figure 1B. fbpA mutants display sensitivity to a broad range of antibiotics o Despite being considered Gram-positive, Mycobacterium cell wall layers create space that resembles the periplasm of Gram-negative bacteria. [6] o Another piece of evidence supporting the impermeability of the Mycobacterial cell wall is the fact that the time it takes for β-lactams to diffuse through the cell wall takes a hundred times longer than it does for Escherichia coli. [7]

Specialized Resistance Mechanisms

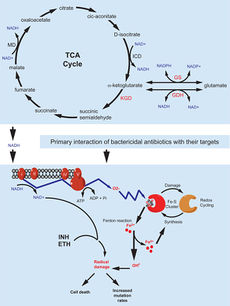

• Modification and degradation of drugs • Modification of drug targets • Efflux pumps o Figure 2.

Figure 2. Bactericidal effects of β-lactams on Wild Type and efflux pump KO mutant M. tuberculosis strains over 7 days. Dashed line indicated number of cells at the start of the experiment. Source: Dinesh N, Sharma S, Balganesh M. Involvement of Efflux Pumps in the Resistance to Peptidoglycan Synthesis Inhibitors in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2013;57(4):1941-1943. doi:10.1128/AAC.01957-12.

At right is a sample image insertion. It works for any image uploaded anywhere to MicrobeWiki. The insertion code consists of:

Double brackets: [[

Filename: Ebola virus 1.jpeg

Thumbnail status: |thumb|

Pixel size: |300px|

Placement on page: |right|

Legend/credit: Electron micrograph of the Ebola Zaire virus. This was the first photo ever taken of the virus, on 10/13/1976. By Dr. F.A. Murphy, now at U.C. Davis, then at the CDC.

Closed double brackets: ]]

Other examples:

Bold

Italic

Subscript: H2O

Superscript: Fe3+

Overall paper length should be 3,000 words, with at least 3 figures with data.

Acquired Resistance

Include some current research in each topic, with at least one figure showing data.

Section 3

Include some current research in each topic, with at least one figure showing data.

Further Reading

References

1. Almeida Da Silva PE, Palomino JC. Molecular basis and mechanisms of drug resistance in mycobacterium tuberculosis: Classical and new drugs. J Antimicrob Chemother 2011 JUL;66(7):1417-30. 2. Christophe T, Jackson M, Jeon HK, Fenistein D, Contreras-Dominguez M, Kim J, Genovesio A, Carralot J, Ewann F, Kim EH, et al. High content screening identifies decaprenyl-phosphoribose 2 ' epimerase as a target for intracellular antimycobacterial inhibitors. Plos Pathogens 2009 OCT;5(10):e1000645. 3. Cui Z, Li Y, Cheng S, Yang H, Lu J, Hu Z, Ge B. Mutations in the embC-embA intergenic region contribute to mycobacterium tuberculosis resistance to ethambutol. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014 NOV;58(11):6837-43. 4. Dinesh N, Sharma S, Balganesh M. Involvement of Efflux Pumps in the Resistance to Peptidoglycan Synthesis Inhibitors in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2013;57(4):1941-1943. doi:10.1128/AAC.01957-12. 5. Mokrousov I, Otten T, Vyazovaya A, Limeschenko E, Filipenko M, Sola C, Rastogi N, Steklova L, Vyshnevskiy B, Narvskaya O. PCR-based methodology for detecting multidrug-resistant strains of mycobacterium tuberculosis beijing family circulating in russia. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases 2003 JUN;22(6):342-8. 6. Nguyen L, Pieters J. Mycobacterial subversion of chemotherapeutic reagents and host defense tactics: challenges in tuberculosis drug development. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2009;49:427-53. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-061008-103123. Review. PubMed PMID: 19281311. 7. Smith T, Wolff KA, Nguyen L. Molecular Biology of Drug Resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Current topics in microbiology and immunology. 2013;374:53-80. doi:10.1007/82_2012_279. 8. Zhao L, Sun Q, Zeng C, Chen Y, Zhao B, Liu H, Xia Q, Zhao X, Jiao W, Li G, et al. Molecular characterisation of extensively drug-resistant mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates in china. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2015 FEB;45(2):137-43. Edited by (your name here), a student of Nora Sullivan in BIOL168L (Microbiology) in The Keck Science Department of the Claremont Colleges Spring 2014.