Mycobacterium tuberculosis review: Difference between revisions

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

==Mycobacterium tuberculosis cell wall structure== | ==Mycobacterium tuberculosis cell wall structure== | ||

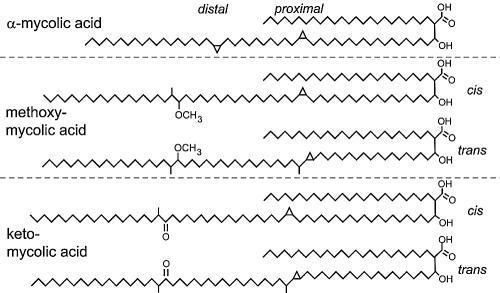

[[Image:Zcm0010521200001.jpg |thumb|500px|right|<b>Figure 3:</b>Chemical structures of mycolic acids from M. tuberculosis. There are five forms of mycolic acids in M. tuberculosis, illustrated with α-mycolic acid from the H37Ra strain and methoxy- and keto-mycolic acids from M. tuberculosis subsp. hominis strains DT, PN, and C. Both cyclopropane rings in α-mycolic acid have the cis configuration. The methoxy- and keto-mycolic acids can have either the cis or trans configuration on the proximal cyclopropane ring.<ref | [[Image:Zcm0010521200001.jpg |thumb|500px|right|<b>Figure 3:</b>Chemical structures of mycolic acids from M. tuberculosis. There are five forms of mycolic acids in M. tuberculosis, illustrated with α-mycolic acid from the H37Ra strain and methoxy- and keto-mycolic acids from M. tuberculosis subsp. hominis strains DT, PN, and C. Both cyclopropane rings in α-mycolic acid have the cis configuration. The methoxy- and keto-mycolic acids can have either the cis or trans configuration on the proximal cyclopropane ring.<ref> [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC544180/ Kuni Takayama,1,2,3,* Cindy Wang,1 and Gurdyal S. Besra, Pathway to Synthesis and Processing of Mycolic Acids in Mycobacterium tuberculosis,doi: 10.1128/CMR.18.1.81-101.2005]</ref>]] | ||

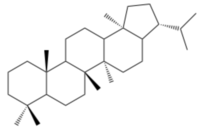

[[Image:Skeleton.png|thumb|200px|right|<b>Figure 4: </b>The general structure of hopane skeleton.<ref name=sigmahopane> [https://www.sigmaaldrich.com/technical-documents/articles/analytix/new-hopane-reference.html Hopane Reference Standards for use as Petrochemical Biomarkers in Oil Field Remediation and Spill Analysis, Amann N., Sigma Aldrich, Accessed May 11th, 2018]</ref>]] | [[Image:Skeleton.png|thumb|200px|right|<b>Figure 4: </b>The general structure of hopane skeleton.<ref name=sigmahopane> [https://www.sigmaaldrich.com/technical-documents/articles/analytix/new-hopane-reference.html Hopane Reference Standards for use as Petrochemical Biomarkers in Oil Field Remediation and Spill Analysis, Amann N., Sigma Aldrich, Accessed May 11th, 2018]</ref>]] | ||

Revision as of 07:20, 25 April 2020

By Boyu Yang

Introduction

Mycobacterium tuberculosis is a deadly human pathogen that has a staggering impact globally, causing infection disease called tuberculosis (TB)(Figure.1). According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, eight million people around the world become sick with TB and there are over two million TB-related deaths worldwide each year.[3] However, most of the infection is latent and only 5 to 10% of this population has a lifetime risk of developing active tuberculosis, either within 1 or 2 years after infection (primary tuberculosis) or thereafter (secondary tuberculosis) [4]

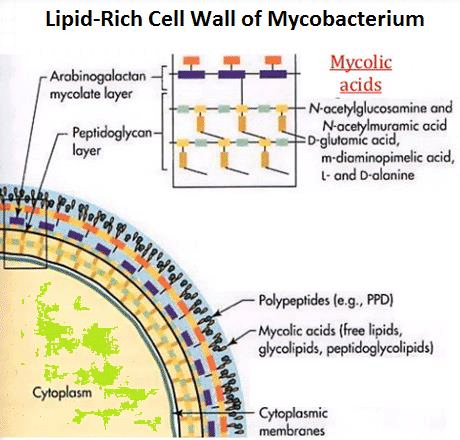

Mycobacterium tuberculosis is a weakly gram-positive, non-motile, rod-shaped bacterium. It is also a facultative intracellular parasite as well as an obligated aerobic. This explains why tuberculosis is a disease typically affects the lungs. Unlike other bacteria that have cell walls mainly composed of peptidoglycan, the major cell wall component of mycobacterium is lipids, mycolic acid (Figure.2). The lipid layer makes it impervious for gram staining, and it shows either gram-positive or gram-negative. More advance methods like acid-fast staining applied to detect the function of Mycobacterium.[5]

Mycobacterium tuberculosis has a low generation time; cell division occurs every 18-24 hours, which is extremely slow compared with other bacteria that normally has a division rate every 20 minutes.[6] The reason is that the mycolic acid has a low permeability which can protects bacterium taking damage from the immune system such as phagosome and macrophage. However, the impervious characteristic also limits nutrient accessibility, decreasing the rate of diffusion and eventually leads to a slower growth rate.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis cell wall structure

Mycolic acid

Mycolic acids,2-alkyl, 3-hydroxy long-chain fatty acids (FAs), are major and specific lipid components of the mycobacterial cell envelope that account for up to 60% of the whole cell dry weight. They are essential for the survival of members of the genus Mycobacterium.[9]In Mycobacterium tuberculosis cell wall, Mycolic acid can be divided into three categories: alpha-myolic acid, methoxyl-myolic acid, and ketone-myolic acid (figure.3). Alpha-mycolic acid has composed more than 70% of the mycolic acid in M. tuberculosis. It is a pure long alkyl chain attached with several cyclopropanes that contribute to the structural integrity of the cell wall complex and protect the bacillus from oxidative stress.[10] Methoxyl-myolic acid made up to 10% to 15% of the mycolic acid. It has extra methoxyl group connected with fatty acid chain. The rest of the 10% to 15% mycolic acid is ketone mycolic acid which has some extra ketone groups attached on fatty acid.[11] Deletion of those cyclopropane rings would lead to significant attenuation in growth and deletion of the keto-mycolates would lead to restricted growth in macrophages.[12] Thus it is highly associated with virulence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

The presence of mycolic plays a significant role in obstructing hydrophilic antimicrobials.[13] Because of this property, hydrophobic antibiotic like rifampicin and fluoroquinolones may be able to cross the cell wall by diffusion. However, the majority of the hydrophilic nutrients and antibiotics like isoniazid are not to diffuse through the lipid layer and they are considered to porin channel instead.[14] Mycobacterium tuberculosis has less abundant than other bacteria and allow a slow uptake rate of nutrient and antibiotic, making it highly resistant to all kinds of antibiotic. Besides resistance to antibiotics, hydrophobic mycolic cell wall also enables tuberculosis to survive inside the macrophage by inhibiting the action of cation proteins, lysozymes, and oxygen radicals, hiding them from the host immune system.

Cord factors

Cord factors (trehalose 6,6′-dimycolate; TDM)is a glycolipid molecule also presence in the cell wall of mycobacterium (figure.3). It locates at the exterior parts of the cell wall and influences the arrangement of mycobacterium into long rod shape, giving it name.[15]

Cord factor is formed by a trehalose sugar and a disaccharide that esterified to two mycolic acid (Figure 3).[16] One of the monosaccharides is connected with mycolic acid at its six carbon and the other monosaccharides also connected with mycolic acid at its six-carbon.[17] Thus, it is named as trehalose 6,6-dimycolate.

Cord factor is extremely toxic to mammalian and it can inhibit polymorphonuclear cell, a category of white blood cells with varying shape of nucleus, migration to the affected area where the infection is present.(10.5) Cord factor could also stimulate the production of TNF (tumor necrosis factors) secretion from the macrophage and T cell. This would lead to a low-grade fever in the infected individuals following by anorexia and eventually result in weight loss. Furthermore, cord factor can induce granuloma formation by its ability to stimulate cytokine production from inflammatory cells in the host.[18]

Wax-D

Wax-D is a lipid complex composed by LAM, sulfatides, and glycolipids and it presents an essential role in preventing oxidation burst inside the phagosome. Sulfatides and glycolipids help mycobacterium tuberculosis in attaching to the macrophages and thusinhibiting the phagosome lysosome fusion. Wax-D also regulates internal acidity by preventing hydrogen ion entering the phagosome, ensuring its DNA replication.[19]

Clinical behavior

Primary infection

Primary infection, the initial phase, occurs in people without specific immunity, generally normal children and young adults who have not previously been exposed to Mycobacterium tuberculosis.(13). It occur when the inhaled bacteria enter the lung would enter the terminal air space and replicate at alveolar macrophage(12). Some of the infected macrophage would migrate to the close lymph node, and eventually disseminate the infection to remote body parts. Primary infection can be tested by observing the present of granuloma, collection of macrophage ,at the infected area (Figure 4). Primary infection can developed into either latent infection or progressive primary infection. Latent infection take place when the M. tuberculosis have been eliminated by the innate immune system or switch into dormant stage and it is hard to differentiate those two stage based on x ray. Progressive primary infection is observed in 5-10% of patients with primary tuberculosis. Just as its name, the infection gradually worsen and worsen at the 1-2 year of the infection. This infection is developed when the immune system failed to control the out break of virus and it is usually happens at the newborn infant whose immune system is underdeveloped(13).

secondary infection

Secondary infection represent the reactivation of a prior latent or dormant infection and there are 5% to 10% of the secondary infection developed from the latent infection. Secondary infection could occur at any point of the host life, either in several months to decades. There are many factors that governs the occurrence of secondary infection, including the immune state of the host. When the host has experience immunity depression, their likelihood to have a secondary infection is high. Secondary infection is alway with other factors. Patients coinfected with Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), organ transplant, and IVDU have more than 10-fold risk than the general population. Besides reactivation, secondary infection can also be caused by reinfection through bacteria outside the host.

Stress tolerance

The abundance and diversity of hopanoid lipids positively influence bacterial resistance to environmental stress, such as the extreme pH, high pressure, non-optical temperature, and high concentration of antibiotic or other lethal chemical compounds.[22] With the help of hopanoid lipids, microbiomes develop different strategies to increase the fitness in non-optical environments. However, most of the detailed mechanisms of stress tolerance induced by the hopanoid lipids remain unclear and require further studies.[22]

Methylation of hopanoid lipids

Researchers found that under extreme conditions, the biosynthesis of hopanoid lipids increases in most bacterial strains.[22] For example, When Rhodopseudomonas palustris is placed under extreme environments, such as high temperature or low pH conditions, those stress induces the activation of the ecfG gene, which is a general stress regulator related gene for the alphaproteobacteria. Due to the expression of ecfG , the response factors and regulators upregulate the expression of hpnP, a gene that codes for hopanoid methylases. Therefore, the expression of hpnP increases the rate of hopanoid lipids methylation in bacteria. Methylation increases the hydrophobic characteristics of hopanoid lipids and further decreases the movements of phospholipids hydrophobic tails, perhaps increasing the bacterial membrane resistance to potential dangers.[23]

Membrane fluidity and permeability

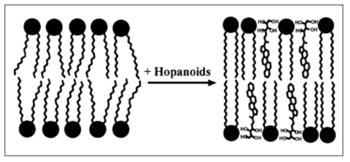

The presence of hopanoid lipids decreases the fluidity and permeability of bacterial membranes. The hydrophobic part of the hopanoid lipids migrates into the bacterial membrane and moves between the phospholipid tails. Thus, hopanoid lipids fill the empty spaces and increase the membrane integrity. The hydrophilic side chains also form strong attractions with other molecules and environments. Overall, the biomembrane becomes more stable, and the leakage of lethal molecules decrease. Under the low pH or high antibiotic conditions, the protons and antibiotic compounds might experience difficulty across the bacterial membranes due to decreased membrane permeability. Therefore, bacteria show higher resistance towards the high concentration of protons, antibiotics, and other lethal molecules.[22]

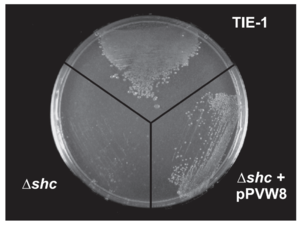

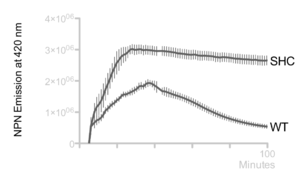

Different hopanoid lipids show different influences on membrane fluidity and permeability. Bile salts show no negative influence on the majority of the Gram-negative bacteria because these chemical compounds are not able to transfer across the outer membrane of the Gram-negative bacteria. Mutated bacteria, without the protection of hopanoid lipids, are vulnerable to the high bile salt conditions.[21] However, different mutations in the same bacteria species show different levels of bile salts sensitivities. shc gene codes for the production of most hopanoid lipids. The Rhodopseudomonas palustris with this mutation shows no bile salts tolerance (Figure 10).[21] The hpnH mutation causes the deficient production of diploptenes and diplopterols. Rhodopseudomonas palustris with this mutation shows resistance towards the bile salts but perform a slower growth rate compared to that of the wild-type strain. The hpnO mutant cannot produce aminobacteriohopanetriols, one essential bacterial hopanoid lipid. This mutant shows no difference in bacterial growth and culture density in the high bile salts concentration compared to the wild-type strain.[22][21]

Orientation and distribution of hopanoid lipids

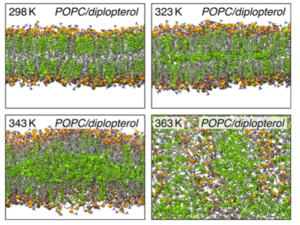

The orientation and the distribution of hopanoid lipids contribute to the bacterial heat resistance. Bacteria, with the help of high concentration of hopanoid lipids, obtain heat protections and keep the homeostasis of their cytoplasm. As the environmental temperature increases, the hopanoid lipids tend to move between two leaflets. In the lipid dynamic simulation at room temperature (298 K), most of the diplopterol molecules gather between the head and the tail of phospholipids. Thus, at milder temperature, the distribution of hopanoid lipids shows a large separation. However, as the temperature increases, the diplopterol molecules migrate to the empty spaces between the tails of two leaflets, largely increasing the thickness of the bacterial membranes and creating substantial protections for thermophiles (Figure 11).[24]

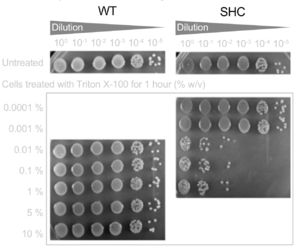

Cooperation with bacterial membrane proteins

Hopanoid lipids might cooperate with outer membrane proteins.[22] The Methylobacterium extorquens mutant strain, with a non-functional hopanoid lipid production, shows an increased detergent sensitivity (Figure 12). Additionally, this strain perhaps cannot pump out the antibiotics due to its non-functional efflux. Researchers studied the accumulation of 1-N-phenylnaphthylamine (NPN), one type of lipophilic dye, in Methylobacterium extorquens. The wild-type strain constantly pumped out NPN, and therefore the intracellular concentration of PNP kept decreasing. However, the intracellular concentration of shc mutant did not change a lot, indicating that perhaps the mutant had deficient efflux (Figure 13).[2] Thus, the hopanoid lipids might contribute and assist the functions of membrane proteins.[22] The collaboration of the hopanoid lipids and membrane proteins enhances bacterial resistance and helps bacteria to maintain the homeostasis between the cytoplasm and extracellular environment. Additionally, bacterial membranes, one of the most significant energy production places, require the presence of effective hopanoid lipids to achieve energy production and storage. Nostoc punctiforme, with a hopanoid lipid mutation, show a decrease in energy storage compared to that of the wild-type strain.[22]

The function of hopanoids is more significant in the stress-resistance specified cells. The filaments of Nostoc punctiforme, one kind of filamentous cyanobacteria, are constituted by the vegetative cells. That specified cells conduct photosynthesis under the environment with abundant nutrients. Therefore, they fix carbon dioxide, showing a high growth and reproduction rate. In these photosynthetic cells, the hopanoid concentration has negligible influence on the stress response. However, under the environment with poor nutrient concentration, Nostoc punctiforme develop the akinete cells through differentiation, which contain higher resistance toward the cold and dry conditions. The akinete cells keep their cellular structure and bacterial activity. They also stay in low energy consumption until they encounter an environment with rich resources. In the akinete cells, a high concentration of hopanoid lipids is detected in bacterial membranes. Previous studies found that the mutant without functional hopanoid lipid showed less resistance to the extracellular resistance. Similarly, Streptomyces coelicolor, one Gram-positive soil bacteria species, forms vegetative cells under nutrient-rich environment. These vegetative cells have a low hopanoid lipid concentration. However, at the end of their life cycle, they produce and accumulate hopanoid lipids, forming spore via sporulation, which can assist their resistance under the extreme conditions.[22]

Nitrogen fixation

Various bacteria, with the ability to produce hopanoids, can fix nitrogen. Bacteria, such as Beijerinckia, Frankia, Anabaena, Burkholderia, etc., show a positive correlation between the hopanoid production and nitrogen fixation.[22] Most nitrogen-fixing bacteria live in close physical correlations with plants, such as alfalfa, soil beans, peas, etc. Both bacteria and plants can take advantage of this relationship. Bradyrhizobium spp. derive energy and other important chemical cofactors from their host plants. The plants also can protect bacteria from stress from the environments, such as competitions with other microbiomes, high proton concentration, etc. Equally, plants benefit from the nitrogen oxides produced by the nitrogen-fixing bacteria, and therefore plants show an enhanced growth rate and outcompete their competitors. There are also free-living nitrogen-fixing microbes, such as Anabaena spp., Frankia spp., etc. However, most of those bacteria do not fix nitrogen without coexisting with plants.

The legume-rhizobia root nodule symbiosis is among one of the most widely studied plants and bacteria associations. The production of hopanoid lipids influences the bacterial symbiosis with the host plants. The Bradyrhizobium spp., with shc mutation, produce a negligible amount of hopanoid lipids. Therefore, this bacteria strain is incapable of integrating with plants. Additionally, different types of hopanoid lipid contribute differently to the bacterial associations with plants. The Bradyrhizobium diazoefficiens with a hpnP mutation cannot produce the extended hopanoids. Their association with the Aeschynomene afraspera results in morphologically disorganized nodules. The Aeschynomene afraspera shows nitrogen starvation, indicating a decreased nitrogen-fixing ability of the hpnP mutant. However, the hpnH mutant, which have less production of 35 carbon hopanoids, cannot form a mature nodule (Figure 14).[25].

The presence of the hopanoid lipids might also contribute to the competition between bacteria to inhabit the hosts. The mutation strain shc, which produces no hopanoid lipids shows an inability in long-term colonization of a plant. Previous studies found that in the beginning, shc mutant grew and developed in host normally. However, after a few days, it started to degenerate and be recycled by its host. On the other hand, the high concentration of hopanoid lipids increases bacterial stress tolerances. For example, the Bradyrhizobium and Burkholderia, both of which contain a high concentration of hopanoid lipids, show resistance to high temperature and low pH conditions. Therefore, in the consideration of global warming and increasing soil acidity, both bacteria might outcompete other bacteria in soil and plants.

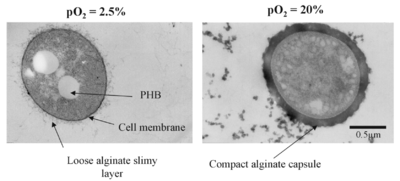

Most of the time, bacteria conduct nitrogen fixation in the low-oxygen concentration environment. Nitrogenase, the core enzyme in nitrogen fixation, is vulnerable in the presence of oxygen. Thus, most of the nitrogen-fixing bacteria exist under the anaerobic environment. Sometimes, nitrogen fixation can also be conducted at high oxygen concentration. Under this condition, bacteria need to develop more sophisticated mechanisms to protect the nitrogenase and achieve nitrogen fixation. The free-living nitrogen-fixing bacteria, Azotobacter vinelandii, develop various ways to fix nitrogen under high oxygen condition. For example, the Azotobacter vinelandii decrease its cellular surface area. Therefore, for each unit of cytoplasm, there are larger protections from the bacterial membranes. Also, under high oxygen condition, it also increased its oxygen consumption via keeping a high respiration rate, thus creating an optional anaerobic environment for nitrogen fixation. The Azotobacter vinelandii also synthesizes alginate to create an alginate capsule, a thick barrier which limits the oxygen fission and protects the nitrogenase from the high oxygen-concentrated surroundings. Under the lower oxygen concentrated environment, Azotobacter vinelandii develops a loose alginate capsule, while under the high concentration, it builds up a compact and thick alginate capsule (Figure 15). Additionally, when the bacteria interact with or inhabit plants, the host plants synthesize leghemoglobin molecules, one type of oxygen-transport metalloproteins. This hemoglobin scavenges oxygen from the root nodules of the leguminous plants, creating an optimal environment for nitrogenase activity[26].

Authored for BIOL 238 Microbiology, taught by Joan Slonczewski, 2018, Kenyon College.

- ↑ Slonczewski, J., and Foster J. W.. Microbiology: An Evolving Science. New York

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Martynov AV, Bomko TV, Nosalskaya TN, Lisnyak Yu.V, Romanova EA, Kabluchko TV, … Farber SB. (2016). TUBERCULOSIS AS AN INFECTIOUS PATHOLOGY OF IMMUNE SYSTEM. Annals of Mechnikov Institute, (3), 8–14. http://doi.org/10.5281

- ↑ uni Takayama,1,2,3,* Cindy Wang,1 and Gurdyal S. Besra4Clin Microbiol Rev. Pathway to Synthesis and Processing of Mycolic Acids in Mycobacterium tuberculosis 2005 Jan; 18(1): 81–101.doi: 10.1128/CMR.18.1.81-101.2005

- ↑ Reinout van Crevel, Tom H. M. Ottenhoff, Jos W. M. van der Meer,Innate Immunity to Mycobacterium tuberculosis,DOI: 10.1128/CMR.15.2.294-309.2002

- ↑ Cudahy P, Shenoi SV (April 2016). "Diagnostics for pulmonary tuberculosis". Postgraduate Medical Journal. 92 (1086): 187–93. doi:10.1136/postgradmedj-2015-133278.

- ↑ Cudahy P, Shenoi SV (April 2016). "Diagnostics for pulmonary tuberculosis". Postgraduate Medical Journal. 92 (1086): 187–93. doi:10.1136/postgradmedj-2015-133278.

- ↑ Kuni Takayama,1,2,3,* Cindy Wang,1 and Gurdyal S. Besra, Pathway to Synthesis and Processing of Mycolic Acids in Mycobacterium tuberculosis,doi: 10.1128/CMR.18.1.81-101.2005

- ↑ Hopane Reference Standards for use as Petrochemical Biomarkers in Oil Field Remediation and Spill Analysis, Amann N., Sigma Aldrich, Accessed May 11th, 2018

- ↑ M. Daffé, P. DraperThe envelope layers of mycobacteria with reference to their pathogenicityDOI: 10.1016/s0065-2911(08)60016-8

- ↑ Yuan Y, Lee RE, Besra GS, Belisle JT, Barry CE 3rdProc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995 Jul 3; 92(14):6630-4.dentification of a gene involved in the biosynthesis of cyclopropane mycolic acids in Mycobacterium tuberculosis.doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.14.6630

- ↑ dentification of a gene involved in the biosynthesis of cyclopropanated mycolic acids in Mycobacterium tuberculosis.Yuan Y, Lee RE, Besra GS, Belisle JT, Barry CE 3rdProc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995 Jul 3; 92(14):6630-4.

- ↑ Yuan Y, Zhu Y, Crane DD, Barry CE 3rd,he effect of oxygenated mycolic acid composition on cell wall function and macrophage growth in Mycobacterium tuberculosis.dOI: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01026.x

- ↑ Draper, P. (1998) The outer parts of the mycobacterial envelope as permeability barriers. Frontiers of Biosciences 3, 1253–1261

- ↑ rias, J., Jarlier, V. and Benz, R. (1992) Porins in the cell wall of mycobacteria. Science 258, 1479–1481DOI: 10.1126/science.1279810

- ↑ Saita, N.; Fujiwara, N.; Yano, I.; Soejima, K.; Kobayashi, K. (1 October 2000). "Trehalose 6,6'-Dimycolate (Cord Factor) of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Induces Corneal Angiogenesis in Rats". Infection and Immunity. 68 (10): 5991–5997. doi:10.1128/IAI.68.10.5991-5997.2000.

- ↑ OLL, H; BLOCH, H; ASSELINEAU, J; LEDERER, E (May 1956). "The chemical structure of the cord factor of Mycobacterium tuberculosis". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 20 (2): 299–309. doi:10.1016/0006-3002(56)90289-x.

- ↑ OLL, H; BLOCH, H; ASSELINEAU, J; LEDERER, E (May 1956). "The chemical structure of the cord factor of Mycobacterium tuberculosis". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 20 (2): 299–309. doi:10.1016/0006-3002(56)90289-x.

- ↑ Perez RL, Roman J, Staton GW Jr, Hunter RL,Extravascular coagulation and fibrinolysis in murine lung inflammation induced by the mycobacterial cord factor trehalose-6,6'-dimycolate.DOI: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.2.8306054

- ↑ Saita, N.; Fujiwara, N.; Yano, I.; Soejima, K.; Kobayashi, K. (1 October 2000). "Trehalose 6,6'-Dimycolate (Cord Factor) of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Induces Corneal Angiogenesis in Rats". Infection and Immunity. 68 (10): 5991–5997. doi:10.1128/IAI.68.10.5991-5997.2000.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedKannenberg1999 - ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 Welander P. V., Hunter R. C., Zhang L., Sessions A. L., Summons R. E., and Newman D. K.. 2009. Hopanoids Play a Role in Membrane Integrity and pH Homeostasis in Rhodopseudomonas palustris TIE-1. JOURNAL OF BACTERIOLOGY, Oct. 2009, Vol. 191, No. 19, p. 6145–6156.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 22.4 22.5 22.6 22.7 22.8 22.9 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedBelin2018 - ↑ Welander P. V., Doughty D. M., Wu C. H., Mehay S., Summons R. E., and Newman D. K.. 2011. Identification and characterization of Rhodopseudomonas palustris TIE-1 hopanoid biosynthesis mutants. Geobiology (2012), 10, 163–177.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Caron B., Mark A. E., and Poger D.. 2014. Some Like It Hot: The Effect of Sterols and Hopanoids on Lipid Ordering at High Temperature. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2014, 5, 3953−3957.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 Kulkarni G., Busset N., Molinaro A., Gargani D., Chaintreuil C., Silipo A., Giraud E., and Newman D. K.. 2015. Specific Hopanoid Classes Differentially Affect Free-Living and Symbiotic States of Bradyrhizobium diazoefficiens. mBio 6(5):e01251-15. doi:10.1128/mBio.01251-15.

- ↑ Sabra W., Zeng A. P., Lunsdorf H., and Deckwer W. R.. 2000. Effect of Oxygen on Formation and Structure of Azotobacter vinelandii Alginate and Its Role in Protecting Nitrogenase. APPLIED AND ENVIRONMENTAL MICROBIOLOGY, Sept. 2000, Vol. 66, No. 9, p. 4037–4044