Shewanella Haliotis: Difference between revisions

| Line 37: | Line 37: | ||

Shewanella Haliotis is a rod-shaped, gram-negative bacteria that reside in the gut biomes of Abalones, which are edible sea snails. The snails are primarily found in Yeosu, South Korea. However, they can live in any warm, marine environment, like Thailand. This is an important bacteria because it infects dairy products and undercooked or raw fish. It can cause extreme necrosis along with fevers, chills, swelling, soreness and erythema (severe rashes.) The strain they originally discovered was also immune to the antibiotics Penicillin and Vancomycin. | Shewanella Haliotis is a rod-shaped, gram-negative bacteria that reside in the gut biomes of Abalones, which are edible sea snails. The snails are primarily found in Yeosu, South Korea. However, they can live in any warm, marine environment, like Thailand. This is an important bacteria because it infects dairy products and undercooked or raw fish. It can cause extreme necrosis along with fevers, chills, swelling, soreness and erythema (severe rashes.) The strain they originally discovered was also immune to the antibiotics Penicillin and Vancomycin. | ||

Pictured | Pictured here are Abalones, the sea snails that the bacteria reside in naturally. | ||

[[File:Abalone.jpg]] | [[File:Abalone.jpg]] | ||

Latest revision as of 15:33, 5 December 2022

Classification

Domain; Bacteria Phylum; Pseudomonadota Class; Gammaproteobacteria Order; Ateromonadales Family; Shewanellaceae Genus; Shewanella

Species

|

NCBI: [1] |

Shewanella Haliotis

Description and Significance

Shewanella Haliotis is a rod-shaped, gram-negative bacteria that reside in the gut biomes of Abalones, which are edible sea snails. The snails are primarily found in Yeosu, South Korea. However, they can live in any warm, marine environment, like Thailand. This is an important bacteria because it infects dairy products and undercooked or raw fish. It can cause extreme necrosis along with fevers, chills, swelling, soreness and erythema (severe rashes.) The strain they originally discovered was also immune to the antibiotics Penicillin and Vancomycin.

Pictured here are Abalones, the sea snails that the bacteria reside in naturally.

Genome Structure

Shewanella Haliotis has a genome with 4.99 Mb, which is average amongst bacteria. It has a circular genome. There were no plasmids discovered within the cell. The genes that were most prevalent within the genome were used for genetic information, environmental and cellular information processing, and signaling.

Cell Structure, Metabolism and Life Cycle

It's a gram-negative cell, which means it has a thin, peptidoglycan layer and a thicker cell membrane. They gain energy from oxygen but in environments with little to no oxygen, such as space, they can gain their energy from metal. A byproduct of their metabolism is electricity, which water treatment and space programs are trying to use to break down their waste and get power in return.

Ecology and Pathogenesis

This organism typically lives in warm, ocean environments, primarily inhabiting the gut biomes of edible sea snails called Abalones. They are usually found in Korea and Thailand. While a symbiote for the snails, they are very harmful to humans. They can inhabit the fish or people who eat the snails. They help break down waste or toxic metals in the environment, causing the substances to be less toxic to the environment.

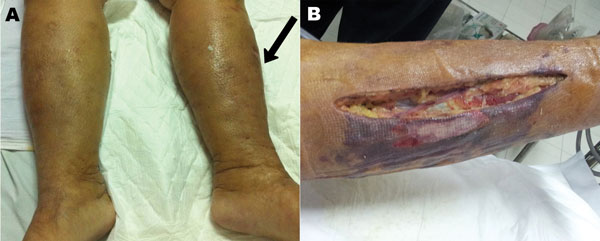

They cause disease in humans through contact with contaminated sea water or through the ingestion of raw or undercooked fish. Very little is known about Shewanella Haliotis so they haven't determined a virulence factor. However, it is more virulent than other organisms of the same species. When a person is infected it can cause fevers, chills, swelling, soreness, rashes, and extreme necrosis.

The pictures below are from a woman in Thailand infected by this bacteria. On the left shows the swelling causes by the disease, and the right is of the necrosis she suffered. Her infection was caused by eating undercooked fish.

References

“Shewanella Haliotis.” Wikipedia, 21 Sept. 2022, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shewanella_haliotis.

Lizárraga, Wendy C., et al. “Complete Genome Sequence of Shewanella Algae Strain 2NE11, a Decolorizing Bacterium Isolated from Industrial Effluent in Peru.” Biotechnology Reports, vol. 33, 31 Jan. 2022, p. e00704, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8816663/, 10.1016/j.btre.2022.e00704. Accessed 13 Nov. 2022.

“Shewanella.” Wikipedia, 11 Mar. 2022, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shewanella#:~:text=One%20of%20the%20roles%20that%20the%20genus%20Shewanella. Accessed 13 Nov. 2022.

“Shewanella Algae - an Overview | ScienceDirect Topics.” Www.sciencedirect.com, www.sciencedirect.com/topics/agricultural-and-biological-sciences/shewanella-algae#:~:text=Virulence%20factors%20for%20Shewanella%20clinical%20isolates%20are%20largely. Accessed 13 Nov. 2022.

Johnson, Michael. “Getting More out of Microbes: Studying Shewanella in Microgravity.” NASA, 5 Aug. 2018, www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/station/research/news/shewanella_microgravity.

Poovorawan, Kittiyod, et al. “Shewanella HaliotisAssociated with Severe Soft Tissue Infection, Thailand, 2012.” Emerging Infectious Diseases, vol. 19, no. 6, June 2013, pp. 1019–1021, wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/19/6/12-1607_article, 10.3201/eid1906.121607. Accessed 13 Jan. 2020.

Author

Page authored by Ben Martin, student of Prof. Bradley Tolar at UNC Wilmington.