Prochlorococcus and Climate Change: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

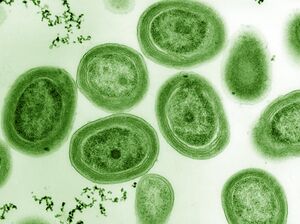

[[Image:Prochlorococcus marinus 2.jpg|thumb|300px|right|This image depicts a Transmission Electron Microscopy image of <I>Prochlorococcus</i> marinus with green coloring. The photo credit for this image belongs to Luke Thompson from Chisholm Lab and Nikki Watson from Whitehead, MIT (2007).]] | [[Image:Prochlorococcus marinus 2.jpg|thumb|300px|right|This image depicts a Transmission Electron Microscopy image of <I>Prochlorococcus</i> marinus with green coloring. The photo credit for this image belongs to Luke Thompson from Chisholm Lab and Nikki Watson from Whitehead, [https://www.flickr.com/photos/prochlorococcus/33750937901/ MIT (2007)].]] | ||

<br>By Zachary Aronson-Paxton<br> | <br>By Zachary Aronson-Paxton<br> | ||

<br>At right is a sample image insertion. It works for any image uploaded anywhere to MicrobeWiki.<br><br>The insertion code consists of: | <br>At right is a sample image insertion. It works for any image uploaded anywhere to MicrobeWiki.<br><br>The insertion code consists of: | ||

Revision as of 16:54, 16 April 2023

By Zachary Aronson-Paxton

At right is a sample image insertion. It works for any image uploaded anywhere to MicrobeWiki.

The insertion code consists of:

Double brackets: [[

Filename: PHIL_1181_lores.jpg

Thumbnail status: |thumb|

Pixel size: |300px|

Placement on page: |right|

Legend/credit: Electron micrograph of the Ebola Zaire virus. This was the first photo ever taken of the virus, on 10/13/1976. By Dr. F.A. Murphy, now at U.C. Davis, then at the CDC. Every image requires a link to the source.

Closed double brackets: ]]

Other examples:

Bold

Italic

Subscript: H2O

Superscript: Fe3+

Sample citations: [1]

[2]

A citation code consists of a hyperlinked reference within "ref" begin and end codes.

To repeat the citation for other statements, the reference needs to have a names: "<ref name=aa>"

The repeated citation works like this, with a forward slash.[1]

What are Prochlorococcus?

Prochlorococcus is a gram negative, coccus bacteria species in the genus cyanobacteria. Prochlorococcus is an aquatic autotroph, found throughout the planet's oceans (Biller et al. 2015). Earth’s oxygen-rich atmosphere is the result of Cyanobacteria and their mass amounts of photosynthesis. Specifically, Prochlorococcus is one of the most abundant autotrophic bacteria in the planet’s oceans (Biller et al. 2015). Prochlorococcus can number up to 70,000 cells in a milliliter of ocean water (Campbell et al. 1998). These vast quantities produce a significant percentage of Earth’s entire photosynthetic output and up to 79 percent of the North Atlantic Ocean’s entire primary production (Biller et al. 2015) (Li 1994). As a result of their large photosynthetic potential, they are a key organism in the fight against climate change and the sequestration of atmospheric carbon. Prochlorococcus uptake more carbon dioxide to undergo photosynthesis than they use up in respiration, creating a stock of carbon inside each organism (Li 1994). When Prochlorococcus dies, it sinks to the bottom of the ocean and is buried, eventually forming oil in what is known as the ocean biological pump (Resplandy et al. 2019). In this way, Prochlorococcus serve as a sink for atmospheric carbon and have an impact on climate change.

The Effect of Climate Change on Prochlorococcus

How does climate change influence the number and efficacy of Prochlorococcus microbes throughout the planet's oceans?

Anthropogenic change is affecting the planet in many ways, most of them unanticipated by scientists. With the projection of continued global change, modeling the future changes set to affect various ecosystems is essential. Since Prochlorococcus is one of the most abundant sinks of atmospheric carbon dioxide, modeling the effects of planetary changes can potentially predict greater, unanticipated changes caused by Prochlorococcus. A decrease in Prochlorococcus and other autotrophic microbes could result in a larger than expected build up of greenhouse gasses as a result of these photosynthetic organisms’ carbon sequestration potential. Greenhouse gas build up, the main cause of global warming, is an essential factor in ecological dynamics across the planet. While Prochlorococcus has evolved for photosynthesis in environments with various different light availability and depths, the rate of anthropogenic change far outpaces Prochlorococcus’ evolution. Various human changes are projected to both increase and decrease the productivity of Prochlorococcus in the Atlantic Ocean.

Decrease in Prochlorococcus Functionality

Rapid global change is expected to decrease some aspects of Prochlorococcus function in the environment. The increase of atmospheric carbon dioxide can actually increase the vulnerability of Prochlorococcus (Hennon et al. 2018). While carbon dioxide is a reactant of photosynthesis and is commonly seen as a mechanism for increased phototrophic production, an increased carbon dioxide concentration can alter Prochlorococcus’ metabolism and microbial interactions with Alteromonas (Hennon et al. 2018). These shifts, a result of ocean acidification related to carbon dioxide levels, could eventually lead to oxidative stress. While oxygen is essential for cellular respiration, it is toxic to many cellular components due to its redox potential. Oxidative stress would lead to an overall decrease in Prochlorococcus productivity, meaning less carbon sequestration and a significant effect on global temperatures.

In addition to oxidative stress, Prochlorococcus functionality is also reduced by human produced plastic litter in the ocean (Tetu et al. 2019). Plastic bags made out of high-density polyethylene (HDPE) and other plastics made out of polyvinyl chloride (PVC) degrade to plastic leachates in the ocean (Tetu et al. 2019). The leachates, present in the marine ecosystem, directly affect the microbial communities around them. Concentration increases in plastic leachates cause decreased levels of photosynthesis in Prochlorococcus (Tetu et al. 2019). The higher the concentration of plastics, the less oxygen produced and the less carbon dioxide taken up. This decreased Prochlorococcus productivity has large implications on the amount of global photosynthesis and atmospheric carbon dioxide. Exposure to plastic leachates also decreases the growth rate of Prochlorococcus (Tetu et al. 2019). Plastic pollution not only impairs photosynthesis in Prochlorococcus, but it also decreases the growth rate, leading to a smaller population size of cells and a further decrease in primary production. Anthropogenic change such as plastic pollution and high atmospheric carbon dioxide result in lower primary production levels of the most abundant aquatic phototroph.

Increase in Range and Population Size

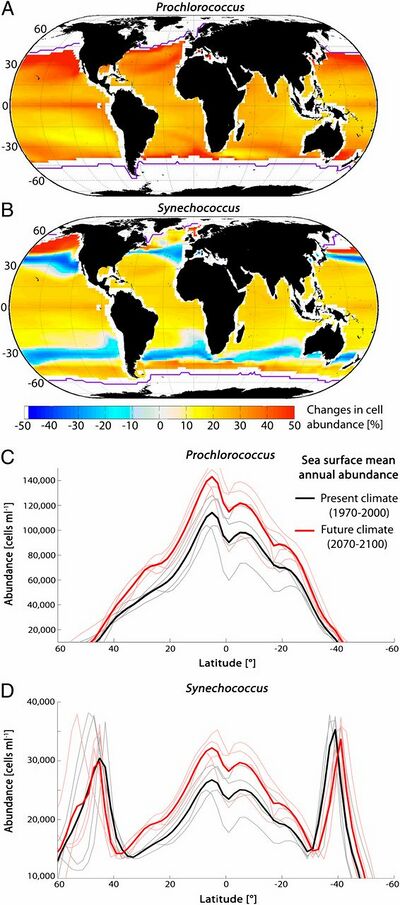

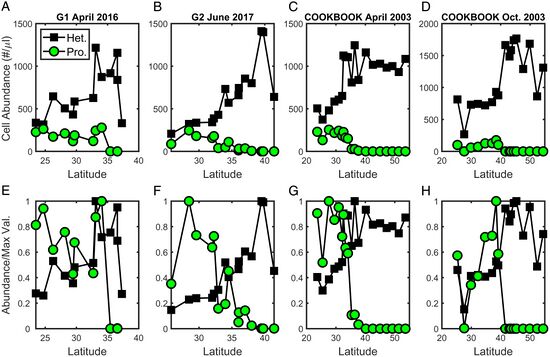

While some aspects of anthropogenic disturbance decrease the functionality of Prochlorococcus, others are shown to increase Prochlorococcus’ range and population size. In accordance with models of projected global warming from the Intergovernmental Program on Climate Change, the Prochlorococcus population is projected to increase by over 40% in a high emission scenario, 25% in a medium emission scenario, and 20% in a low emission scenario (Flombaum and Martiny 2021). The rising surface temperature creates more habitable space for Prochlorococcus across the Earth’s oceans (Flombaum and Martiny 2021). However, ecological interactions are difficult to predict due to the large amount of unknown factors that could be at play (Flombaum and Martiny 2021). Despite this relative uncertainty, a new ecological niche model designed to predict the effects of climate change on oceanic phototrophs predicted that Prochlorococcus would increase in population size and ecosystem niche dominance (Xiao et al. 2019).

Microbe Interaction

Furthermore, anthropogenic change is predicted to shift Prochlorococcus’ microbial interactions in its surrounding ecosystem. Other autotrophic bacteria are also affected by human change, creating a novel dynamic ecosystem (Fu et al. 2007). Increasing temperatures and atmospheric carbon dioxide from global warming are projected to affect strains of autotrophic microbes differently (Fu et al. 2007). While Prochlorococcus is projected to display some increased population size due to human change, Synechococcus is modeled to be even better suited to the changing climate (Fu et al. 2007). This shift in niche dominance would alter the microbial community dynamics, potentially decreasing the prominence in Prochlorococcus in the ocean. While Prochlorococcus may be outcompeted in the future by Synechococcus, both of these bacteria are oceanic phototrophs, taking up carbon dioxide and releasing oxygen back into the atmosphere. While these interactions are projected to fit the changing environmental conditions, ecosystem modeling has a high degree of error because it must overlook many variables that could be essential to the ecosystem.

Conclusion

Widespread anthropogenic change is currently occurring across the planet today, altering the temperature, species dynamics, and ecosystems of almost all life on Earth. Prochlorococcus is no different. The oceanic autotroph is responsible for almost all of the primary production in the planet's oceans (Biller et al. 2015). This primary production provides an essential carbon sink for the planet, potentially altering the trajectory of global climate change. Some aspects of anthropogenic change including plastic leachate pollution (PVC and HDPE) and oxidative stress are projected to decrease Prochlorococcus’ population size and photosynthetic potential (Tetu et al. 2019). These factors would then lead to less primary production in the oceans, less atmospheric carbon dioxide taken up by these microbes, and a compounding effect on greenhouse gasses and climate change. However, fortunately for the planet, the increased surface temperature caused by widespread global warming is actually predicted to increase Prochlorococcus’ range and population size, counteracting some of the negative effects of human change on these microbes (Flombaum and Martiny 2021). While the increase is beneficial in the fight against climate change, ecosystem dynamics are extremely difficult to predict so this potentially large carbon sink should not be depended on. An example of how variable ecosystem dynamics can be is seen in the projected competition between Synechococcus and Prochlorococcus. While both of these microbes have a similar impact on climate change, Synechococcus is projected to eventually outcompete Prochlorococcus as the most dominant oceanic autotroph (Fu et al. 2007). While many changes are projected to occur in Prochlorococcus’ ecosystem, climate change is projected to have both positive and negative effects on this important microbe.

Prochlororcoccus’ Impact on the Oceans

How does Prochlorococcus’ large scale photosynthetic processes affect ocean ecosystems?

Due to Prochlorococcus’ impact on the surrounding ecosystem, large-scale effects on Prochlorococcus as a result of climate change are amplified across the entire ecosystem. Despite Prochlorococcus’ small size, it has an enormous impact on the environment around it. Since Prochlorococcus is a phototroph, it makes up the primary producer base of the food system, sequestering carbon into glucose that can be metabolized into energy by heterotrophs. The vitality of the marine ecosystem is largely dependent on autotrophs such as Prochlorococcus. Prochlorococcus impacts the surrounding ecosystem through diverse microbial interactions, both mutualistic and predatory, as well as through its own intraspecies variation.

Interspecific Interactions

Interspecific interactions are the building blocks of ecosystems, contributing strongly to population dynamics, biodiversity, and species distribution (Ovaskainen et al. 2013). Prochlorococcus is at the base of the trophic cascade, meaning that it is often preyed upon by oceanic heterotrophs. One such interaction occurs between Prochlorococcus and zooplankton (Follett et al. 2022). While Prochlorococcus is often found nearer to the equator than the poles, climate change is predicted to expand its viable range and increase its population size (Flombaum and Martiny 2021). However, the predatory relationship with zooplankton has been modeled to be a range-constricting factor on Prochlorococcus (Follett et al. 2022). This community dynamic has complex consequences on the future of Prochlorococcus and the entire oceanic ecosystem. If Prochlorococcus’ range is constricted based on predation and not surface temperature, as was previously predicted, then global warming would not increase the number of Prochlorococcus and primary production would not increase in the oceans (Follett et al. 2022). Despite this prediction, ecosystem modeling is often inaccurate and the outcomes are unexpected.

In addition to predation, Prochlorococcus influences the ecosystem by forming mutualistic relationships with oceanic heterotrophs. While Prochlorococcus uses the carbon they sequester through photosynthesis to produce glucose and undergo respiration, Prochlorococcus sequester more carbon than they actually need (Szul et al. 2019). Prochlorococcus have the tendency to release some of their extra carbon into their surroundings (from 9 to 24% of their total sequestered carbon), especially when exposed to nitrogen and other nutrient limited environments (Bertilsson et al. 2005) (Szul et al. 2019). Some of the excreted carbon, mainly carboxylic acids, is attractive to oceanic heterotrophs (Bertilsson et al. 2005). Prochlorococcus and the organic carbon it releases can form a community of dependent heterotrophs, increasing biodiversity and demonstrating the importance of Prochlorococcus in the oceanic ecosystems (Bertilsson et al. 2005).

Intraspecific Variation

Prochlorococcus is present throughout the planet's oceans, in many different ecosystems. As a result of its ecosystem variation, Prochlorococcus has evolved different strains suited to fill many specific niches (Biller et al. 2015). In fact, while these strains are still Prochlorococcus, they contain streamlined genomes that differ from each other (Biller et al. 2015). These strains, such as MED4, a strain adapted to high light intensities and found in the upper levels of the ocean, and MIT9313, a low light strain found deeper in the oceans, serve different ecosystem functions (Sher et al. 2011). As a result of MIT9313 being adapted to low light levels, it forms greater mutualistic relationships with heterotrophic bacteria than the high-light adapted MED4 (Sher et al. 2011). The ecological differences between Prochlorococcus strains is important for ecosystem health, especially when considering the future impacts of climate change. Prochlorococcus strains respond differently to changes in temperature, light availability, and oceanic currents (Malstrom et al. 2010). A large change in these variables, like what is predicted for climate change could result in a shift in Prochlorococcus ecotype prevalence, disturbing ecological relationships and the surrounding ecosystem.

Conclusion

Overall, Prochlorococcus is responsible for a large part of oceanic ecosystem dynamics due to their relationships with other microbes and their intraspecies variation. Prochlorococcus’ ability to photosynthesize makes them a base of the ocean’s ecosystem; they are essential in order for other ocean life to survive. While currently their ecological relationships act as a stabilizing force in the oceans, they are dependent on abiotic factors. The main abiotic factors that Prochlorococcus ecology is dependent on, temperature, light, and currents, are predicted to change dramatically through climate change. This dramatic change could potentially disrupt many of Prochlorococcus’ relationships, causing large scale change across the oceans.

Prochlororcoccus’ Effect on the Changing Planet

Does Prochlorococcus have a direct impact on the planet’s atmosphere and the process of climate change?

Include some current research, with at least one figure showing data.

Conclusion

References

Authored for BIOL 238 Microbiology, taught by Joan Slonczewski, 2023, Kenyon College