Chytridiomycota: Difference between revisions

| Line 37: | Line 37: | ||

==Ecology== | ==Ecology== | ||

[[Image:chy_all_sph.jpg|thumb|300px|right|''Allomyces sporophyte'' [http://www.csupomona.edu/%7Ejcclark/classes/bot125/resource/survey/chytridiomycota.html Survey of the botanical Phyla: Chytridiomicota by Curtis Clark.]]] | |||

Chytridomycota usually inhabit freshwater ecosystems. In fact, they are dependent on the presence of water to survive. However, Chytridiomycota often dwell within host organisms, which can be plants or animals. They live saprophytically and parasitically. Because Chytridiomycota often feed on decaying organisms, they are important decomposers. While this is an important function, Chytridiomycota can also have a negative impact on human produce, particularly ''Synchytrium endobioticum'', the species that causes potato wart. Others, such as ''Olpidium brassicae''(the "Big Vein" virus in lettuce), are parasitic, but actually do little damage to the host organism as a whole. While this is not true of all species, some, such as ''Rhizophlyctis rosea'' and ''Allomyces anomalus ''have structures that allow them to survive draughts or excessive heat. | Chytridomycota usually inhabit freshwater ecosystems. In fact, they are dependent on the presence of water to survive. However, Chytridiomycota often dwell within host organisms, which can be plants or animals. They live saprophytically and parasitically. Because Chytridiomycota often feed on decaying organisms, they are important decomposers. While this is an important function, Chytridiomycota can also have a negative impact on human produce, particularly ''Synchytrium endobioticum'', the species that causes potato wart. Others, such as ''Olpidium brassicae''(the "Big Vein" virus in lettuce), are parasitic, but actually do little damage to the host organism as a whole. While this is not true of all species, some, such as ''Rhizophlyctis rosea'' and ''Allomyces anomalus ''have structures that allow them to survive draughts or excessive heat. | ||

| Line 44: | Line 45: | ||

Through their research with chytridiomycosis, Olsen et. al. (2004) have developed a staining protocol to facilitate the often difficult diagnosis of this disease. The difficulty lies in the invasiveness and insensitivity of standard detection methods, which usually involve taking toe clippings from the amphibian. Other researchers have been working in the field of detection as well. Annis et. al. (2004) have developed a method of detection which is a polymerase chain-reaction based assay. Boyle et. al. (2004) have also developed a new method of detection, a real-time PCR Taquin assay. Van Ells et. al. (2003) developed a method of immunohistochemical staining which proved to be a very effective method of diagnosis, because infected was made highly visible. Some researchers focus on treatment instead of detection. Johnson et. al. (2003) compared the efficacy of chemical disinfectants, UV light, dessication, and heat in treating chytridiomycosis. Most methods were effective; cultures did not survive drying and were sensitive to heat. Chemical treatments were also highly effective, although concentration and exposure were critical factors in their efficacy. The only treatment method that did not work was exposing the cultures to UV light. Other researchers have not looked at either detection or treatment, but instead studied the effects of the virus on community interactions between the gray treefrog, ''Hyla chrysoscelis'', and eastern newts, ''Notophthalmus viridescens''. Their work indicates that the effects are complex and indirect. | Through their research with chytridiomycosis, Olsen et. al. (2004) have developed a staining protocol to facilitate the often difficult diagnosis of this disease. The difficulty lies in the invasiveness and insensitivity of standard detection methods, which usually involve taking toe clippings from the amphibian. Other researchers have been working in the field of detection as well. Annis et. al. (2004) have developed a method of detection which is a polymerase chain-reaction based assay. Boyle et. al. (2004) have also developed a new method of detection, a real-time PCR Taquin assay. Van Ells et. al. (2003) developed a method of immunohistochemical staining which proved to be a very effective method of diagnosis, because infected was made highly visible. Some researchers focus on treatment instead of detection. Johnson et. al. (2003) compared the efficacy of chemical disinfectants, UV light, dessication, and heat in treating chytridiomycosis. Most methods were effective; cultures did not survive drying and were sensitive to heat. Chemical treatments were also highly effective, although concentration and exposure were critical factors in their efficacy. The only treatment method that did not work was exposing the cultures to UV light. Other researchers have not looked at either detection or treatment, but instead studied the effects of the virus on community interactions between the gray treefrog, ''Hyla chrysoscelis'', and eastern newts, ''Notophthalmus viridescens''. Their work indicates that the effects are complex and indirect. | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

Revision as of 20:04, 15 June 2006

|

NCBI: |

Classification

Higher order taxa:

Eukaryota; Fungi/Metazoa group; Fungi

Species:

Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, Spizellomyces punctatus, Rhizophydium sphaerotheca

Description and Significance

Chytridiomycota are the smallest and simplest fungi. They emerged soon after the Precambrian period, and are ancestors to all Fungi. The first Chitridiomycota were found in northern Russia. There are three orders within Chytridiomycota: Chytridiales, Blastocadiales, and Monoblepharidales.

Genome Structure

There are many different species within the classification of Chytridiomycota, and all have different genomes. For example, the species , there are eight mitochondrially-encoded tRNAs, and it is believed that they have at least one base pair mismatch at the first three positions of their aminoacyl acceptor stems. Bullerwell and Gray (2005) have developed a method of tRNA editing using the mitochondiral extract of S. punctatus. 5' tRNA editing occurs in the mitochondria of this species, as well as in the chytridiomycete order Monoblepharidales. However, it does not occur in Rhizophydium brooksianum. Laforest et. al. (2004) believe that 5' tRNA edition evolved twice independently within Chytridiomycota. The genome structure of Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis shows only five variable nucleotide positions, meaning it has a low level of genetic variation. Other characteristics of the B. dendrobatidis genome include nearly fixed heterozygous genotypes as well as chromosome lengtgh polymorphisms. The genes that encode alpha- and beta-tubulins are useful for encoding fungal phylogeny. Corradi et. al. (2004) studied the genetic similarities between members of Chrytidiomycota and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF). They found large evolutionary differences at the amino-acid level, but at the mitochondiral level, differences were significantly smaller. Anaerobic chytridiomycetes contain an enzyme called pyruvate formate lyase, which is essential for f.ermentative formate production. This enzyme exists in the genetic structure of only one other eukaryotic lineage, chlorophytes.

Cell Structure and Metabolism

Chytridiomycota have unicellular or mycelial thalli. Cell walls are made of chitin, although one group has walls made of cellulose. Cell growth can be unicellular, or it can occur in the multicellular mycelium of aseptate hyphae. The thallus is typcially unicellular; it may also have limited hyphal growth. It is not considered mycelial. Hyphal cells are coenocytic, although this is not the case where there are reproductive structures. The ultrastructure of the zoospore is a definitve characteristic of Chytridiomycota. In the structure, ribosomes are aggregated around a nucule that is not enclosed in a nuclear cap. A nuclear cap is an extension of the nuclear membrane. Chytridiomycota have one or two flagella.

Chytridiomycota feed on both living and decaying organisms. They are heterotrophic.

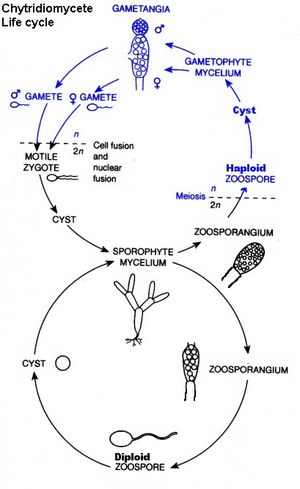

Asexually, Chytridiomycota reproduce through the use of zoospores. In asexual reproduction, zoospores will swim until a desireable substrate is located. The zoospore attaches itself, feeds off its host; the cytoplasm grows, meiotic divisions occur, and a cell wall forms around the original zoospore. Protoplasm increases as the cell continues to develop. Finally, cleavage of the protoplasm occurs, which produces individual zoospores that are released through a pore. Sexual reproduction is haploid dominant. It also depends on the isomorphic alternation of generations. The haploid thallus, called the gametothallus, produces female and male gametes. These occur in pairs and are terminal and subterminal. Male gametes are orange-colored, while female gametes are colorless. In addition, female gametes are much larger than male gametes. Males are attracted to females when they produce the hormone sirenin, and females are attracted to males when they produce the hormone parisin.

The diploid thallus is called the sporothallus. The sporothallus produces two types of zoosporgia: zoosporgangium (meitosporangium) and resistant sporangium (meiosporangium). Zoosporangia produce diploid zoospores, which can function as a means of asexual reproduction. Sexual reproduction may be isogamous, anisogamous, or oogamous. One species, Allomyces macrogynus, has a sporic life cycle, something that occurs in plants but is rare to fungi. A. macrogynus is an example of an anisogamous species.

Ecology

Chytridomycota usually inhabit freshwater ecosystems. In fact, they are dependent on the presence of water to survive. However, Chytridiomycota often dwell within host organisms, which can be plants or animals. They live saprophytically and parasitically. Because Chytridiomycota often feed on decaying organisms, they are important decomposers. While this is an important function, Chytridiomycota can also have a negative impact on human produce, particularly Synchytrium endobioticum, the species that causes potato wart. Others, such as Olpidium brassicae(the "Big Vein" virus in lettuce), are parasitic, but actually do little damage to the host organism as a whole. While this is not true of all species, some, such as Rhizophlyctis rosea and Allomyces anomalus have structures that allow them to survive draughts or excessive heat.

Anaerobic rumen fungi, such as Orpinomyces joyonii, inhabit the guts of cattle, sheep, and goats. These fungi live in anaerobic conditions and play an imporant part in the digestive process. They help process plant matter while obtaining food. They are so effective that they make their hosts some of the most effective animals at utilizing cellulose. In addition, some species of anaerobic rumen fungi are used for other purposes. Xue et. al. (1996) cloned microbial non-starch polysaccharide hydrolases from Neocallimastix patriciarum. They found that the genes within these hydrolases were valuable for the production of genetically-engineered cereal crops.

There is a disease that comes from the Chytridiomycota classification. Chytridiomycosis is a fungal infection of amphibians. The disease is found in keratinised tissue, which includes the mouthparts of tadpoles. One of the main symptoms of chytridiomycosis is a thickened epidermis (hyperkeratosis). It is fatal, and has caused amphibian population decline on several continents. Treatment is possible if the infection is caught early, but not always effective. One important characteristic of chytridiomycosis is the way it behaves at different temperatures. The pathogenicity of the disease is enhanced at lower tempeartures, as is victim mortality rate. The origin of the disease has been unknown for quite some time. However, the work of Weldon et. al. (2004) has posed several theories about the disease. They found that the earliest known case of chytridiomycosis occurred in 1938. They also discovered that this infection existed in Africa for 23 years before any reported cases outside of Africa. They concluded that the fungus originated in Africa, and was introduced to other continents in the mid-1930s.

Through their research with chytridiomycosis, Olsen et. al. (2004) have developed a staining protocol to facilitate the often difficult diagnosis of this disease. The difficulty lies in the invasiveness and insensitivity of standard detection methods, which usually involve taking toe clippings from the amphibian. Other researchers have been working in the field of detection as well. Annis et. al. (2004) have developed a method of detection which is a polymerase chain-reaction based assay. Boyle et. al. (2004) have also developed a new method of detection, a real-time PCR Taquin assay. Van Ells et. al. (2003) developed a method of immunohistochemical staining which proved to be a very effective method of diagnosis, because infected was made highly visible. Some researchers focus on treatment instead of detection. Johnson et. al. (2003) compared the efficacy of chemical disinfectants, UV light, dessication, and heat in treating chytridiomycosis. Most methods were effective; cultures did not survive drying and were sensitive to heat. Chemical treatments were also highly effective, although concentration and exposure were critical factors in their efficacy. The only treatment method that did not work was exposing the cultures to UV light. Other researchers have not looked at either detection or treatment, but instead studied the effects of the virus on community interactions between the gray treefrog, Hyla chrysoscelis, and eastern newts, Notophthalmus viridescens. Their work indicates that the effects are complex and indirect.

References

The Bio-Web Group. Division Chytridiomycota.

Clark, Curtis. Survey of the botanical Phyla: Chytridiomycota.

Maksymica, Monica. Kingdom Fungi: Chytridiomycota.

Slonczewski, Joan. Microbiology.