Neisseria: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Biorealm}} | {{Biorealm Genus}} | ||

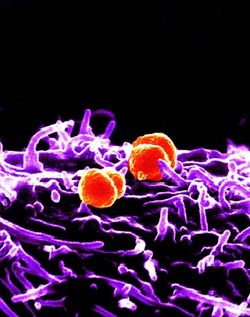

[[Image:ng-lym1.jpg|thumb|250px|right|''Neisseria gonorrhoeae''. From [http://neisseria.org/ng/images/ Dr. Ian Boulton.]]] | [[Image:ng-lym1.jpg|thumb|250px|right|''Neisseria gonorrhoeae''. From [http://neisseria.org/ng/images/ Dr. Ian Boulton.]]] | ||

| Line 14: | Line 10: | ||

===Species:=== | ===Species:=== | ||

{| | |||

| height="10" bgcolor="#FFDF95" align="center" | | |||

'''NCBI: [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Taxonomy/Browser/wwwtax.cgi?mode=Info&id=482&lvl=3&lin=f&keep=1&srchmode=1&unlock Taxonomy] Genome: -''<font size="2">[http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genomes/framik.cgi?db=Genome&gi=155 Neisseria meningitidis MC58] -[http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genomes/framik.cgi?db=Genome&gi=156 Neisseria meningitidis Z2491 ]</font>'' ''' | |||

|} | |||

''Neisseria animalis; N. bacilliformis; N. canis; N. cinerea; N. dentrificans; N. dentiae; N. elongata; N. flava; N. flavescens; N. gonorrhoeae; N. iguanae; N. lactamica; N. macacae; N. meningitidis; N. mucosa; Neisseria perflava; Neisseria pharyngis; Neisseria polysaccharea; N. sicca; N. subflava; N. weaveri; N. sp.'' | ''Neisseria animalis; N. bacilliformis; N. canis; N. cinerea; N. dentrificans; N. dentiae; N. elongata; N. flava; N. flavescens; N. gonorrhoeae; N. iguanae; N. lactamica; N. macacae; N. meningitidis; N. mucosa; Neisseria perflava; Neisseria pharyngis; Neisseria polysaccharea; N. sicca; N. subflava; N. weaveri; N. sp.'' | ||

Revision as of 16:22, 15 August 2006

A Microbial Biorealm page on the genus Neisseria

Classification

Higher order taxa:

Bacteria; Proteobacteria; Betaproteobacteria; Neisseriales; Neisseriaceae

Species:

|

NCBI: Taxonomy Genome: -Neisseria meningitidis MC58 -Neisseria meningitidis Z2491 |

Neisseria animalis; N. bacilliformis; N. canis; N. cinerea; N. dentrificans; N. dentiae; N. elongata; N. flava; N. flavescens; N. gonorrhoeae; N. iguanae; N. lactamica; N. macacae; N. meningitidis; N. mucosa; Neisseria perflava; Neisseria pharyngis; Neisseria polysaccharea; N. sicca; N. subflava; N. weaveri; N. sp.

Description and Significance

Neisseria menigitidis is responsible for a large amount morbidity and mortality throughout the world with septicemia and meningitis cases estimated to be between 500,000 and 1 million every year (Dietrich et al. 2003). Neisseria gonorrhoeae is the agent of the sexually transmitted disease gonorrhea that is second in cases reported only to chlamydia (CDC).

Genome Structure

A study was done comparing genes between Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Neisseria meningitidis to see the basis of their different pathogenicities. Of the N. Meningitidis clones studied, the majority had no homology with anything but general neisserial sequences. Most of the differences between the two genomes seemed to be clustered in three regions, one being the region containing the capsule-related genes. (Tinsley and Nassif 1999)

Cell Structure and Metabolism

Neisseria are diplococci with their adjacent sides flattened. They are "aerobic, strongly oxidase-positive, have an oxidative metabolism, are susceptible to drying, and are fastidious (growth is inhibited by free fatty acids)" (Douglas F. Fix). The four types of N. gonorrhoeae are T1, T2, T3, and T4 depending on the presence of fimbriae; the bacteria uses the fimbriae to attach onto host cells and are avirulent without them. N. meningitidis are grouped by the antigenic character of the cells capsular polysaccharide: some groups include A, B, C, W-135, and Y (Douglas F. Fix).

Ecology

Neisseria menigitidis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae are both human pathogens that infect the body differently. Several of Neisseria can be found in aquatic environments worldwide.

Pathology

Neisseria bacteria are responsible for the diseases meningitis and gonorrhoeae. Gonorrhea, which is caused by Neisseria gonorrhoeae, is a sexually transmitted disease that is second only to chlamydia in reported cases to the CDC; 361,705 cases were reported in 2001. The bacteria begins infection through colonizing mucosal surfaces; humans are the only host of this bacteria and it is transmitted through sexual contact. In men, the probability of acquiring the disease from a single exposure is about 25%; in women, it is about 40%; in women taking oral contraceptives, it is about 100%.

The bacteria uses fimbriae to attach to host cells: cells without fimbriae are avirulent. It also produces cytotoxic substances, one of which is the LPS endotoxin, that damage epithelial cells with cilia found in fallopian tubes. In response to host immune responses, N. gonorrhoeae produces an extracellular protease that "cleaves a proline-threonine bond in immunoglobulin IgA" which causes loss of antibody activity. Although some strains are unfortunately become immune to certain antibiotics, most can still be treated with antibiotics and if caught in time, won't leave permanent damage to the patient. (Douglas F. Fix) Men with gonorrhea may not have any symptoms; however, if symptoms do occur, they occur 3 - 6 days after infection and include inflammation of the urethra, burning when urinating, and a pus discharge from the penis. Women may also not show symptoms, when symptoms do occurs, they can include a greenish-yellow vaginal discharge from the cervix and an itchy and red vulva. This infection might possibly lead to Pelvic Inflammatory Disease in some women, if it develops in the uterus and fallopian tubes, it can lead to severe pain, fever, infection of other parts of the body, and infertility. Newborn infants can contract Gonorrhea eye infections if they pass through an infected mother's birth canal. This results in pus in the eye and potential blindness if not treated (Afraidtoask.com).

Meningococcal infection begins when the bacteria colonizes the nasopharyngeal and tonsillar mucosa. First the bacteria adheres to the tissue, then the meningococci initiates endocytosis, crosses the epithelial barrier, and therefore gains access to the bloodstream. The characteristic movement of meningococci is tropism towards the central nervous system. Once the bacteria crosses the blood-brain barrier, the host then develops purulent meningitis. The bacteria has to be able to escape innate and acquired immune responses. "Excessive exchange and mutation of their DNA, including phase variation due to slipped-strand mispairing, ensures the existence of a highly diverse bacterial population, which is an important condition for the preadaptation to specific microenvironmental conditions" (Dietrich et al. 2003).

Type B, the most common type in the Western world, does not yet have a vaccine; however, types A, C, Y, and W have working vaccines that prevent bacterial infection. In addition it must be able to rapidly adapt and have different virulence mechanisms due to the changing environments during different stages of infection; one way in which the meningococci do this is at the transcriptional level. One example of this is a transcriptional regulator that causes cross talk between meningococci and the target cells during infection. (Dietrich et al. 2003) The symptoms of meningitis include a high fever, skin rash, severe headache, and a stiff neck. Accoring to SRS, "as many as 10% of the population in the UK will be carrying the bacterium at any one time on the mucosal surfaces of the nose and throat" (SRS).

References

General:

- Neisseria.org

- The Sanger Institute: Neisseria meningitidis

- Fix, Douglas F: Neisseria

- Dietrich, Guido, Sebastian Kurz, Claudia Hubner, Christian Aepinus, Stephanie Theiss, Matthias Guckenberger, Ursula Panzner, Jacqueline Weber, and Matthias Frosch. 2003. "Transcriptome analysis of Neisseria meningitidis during infection." Journal of Bacteriology, vol. 185, no. 1. American Society for Microbiology. (155-164)

Genome Structure:

- Tinsley, C. R. and X. Nassif. 1996. "Analysis of the genetic differences between Neisseria meningitidis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae: Two closely related bacteria expressing two different pathogenicities." Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., vol 93. (11109-11114)

Pathology:

- CDC: Neisseria gonorrnoeae: Gonorrhea

- Afraidtoask.com: The STD Guide: Gonorrhea