Shock chlorination: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

==Introduction== | ==Introduction== | ||

From swimming pools to wells, chlorine is a common chemical used to disinfect water sources. | From swimming pools to wells, chlorine is a common chemical used to disinfect water sources. About a century ago, the process of chlorination was introduced in order to prevent the spread of diseases such as typhoid or cholera. Over time, the process has modified, with the EPA (Environmental Protection Agency) beginning to implement the use of chloramine, a closely related compound, instead<sup>1</sup>. | ||

Due to safety concerns, hypochlorite (bleach) is the most commonly used compound to conduct shock chlorination<sup> | Due to safety concerns, hypochlorite (bleach) is the most commonly used compound to conduct shock chlorination<sup>2</sup>. Hypochlorite is used in one of three forms: commercial bleach (approx. 3.5-5% concentration), calcium hypochlorite (Ca(OCl)<sub>3</sub>; 65-70% concentrated), or sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl; about 12% concentration)<sup>2</sup>. These forms of hypochlorite are not as pure as chlorine gas, and will degrade in strength when in storage. However, like chlorine gas, they also react with water to form a disinfectant, hypochlorous acid (HOCl). | ||

==Microbial agents== | ==Microbial agents== | ||

Frequently, microbial factors infiltrate water sources through fecal matter. Many types of bacterial pathogens can initiate waterborne illnesses, including enteric bacteria, protozoa, or viruses<sup> | Frequently, microbial factors infiltrate water sources through fecal matter. Many types of bacterial pathogens can initiate waterborne illnesses, including enteric bacteria, protozoa, or viruses<sup>4</sup>. <br> | ||

Due to the variety of species that can inhabit water sources, it comes as no surprise that chlorine has varying affects on the types of microbes. Though time and concentration can eliminate virtually every species, some species remain resistant to the process. Species such as <i>Vibrio cholera</i> have been tested to last approximately 30 days in drinking water sources, while toxigenic <i>E.coli</i> can last 90 days<sup> | Due to the variety of species that can inhabit water sources, it comes as no surprise that chlorine has varying affects on the types of microbes. Though time and concentration can eliminate virtually every species, some species remain resistant to the process. Species such as <i>Vibrio cholera</i> have been tested to last approximately 30 days in drinking water sources, while toxigenic <i>E.coli</i> can last 90 days<sup>5</sup>. Survival techniques include cysts, spores, absorption, and intracellular survival and growth. Other species will remain viable, but no longer culturable. | ||

===<i>Helicobacter pylori</i>=== | ===<i>Helicobacter pylori</i>=== | ||

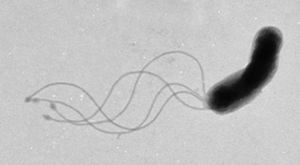

[[Image:Helicobacterpylori0.jpeg|thumb|300px|right|Electron micrograph of <i>Helicobacter pylori</i>, a microbe commonly found in public water sources. Courtesy: [http://mib.uga.edu/research/labs/hoover Timothy Hoover (Franklin College)]]] | [[Image:Helicobacterpylori0.jpeg|thumb|300px|right|Electron micrograph of <i>Helicobacter pylori</i>, a microbe commonly found in public water sources. Courtesy: [http://mib.uga.edu/research/labs/hoover Timothy Hoover (Franklin College)]]] | ||

<i>[http://microbewiki.kenyon.edu/index.php/Helicobacter_pylori Helicobacter pylori]</i> is known to cause gastritis and peptic ulcers. | <i>[http://microbewiki.kenyon.edu/index.php/Helicobacter_pylori Helicobacter pylori]</i> is known to cause gastritis and peptic ulcers. | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

Studies done in Peru<sup> | Studies done in Peru<sup>6</sup> and Japan<sup>7</sup> have shown the presence of the bacteria in public water sources, proving its possibility as a waterborne microbe. | ||

===<i>Cryptosporidium</i>=== | ===<i>Cryptosporidium</i>=== | ||

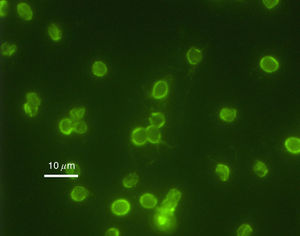

[[Image:Cryptosporidium1.jpeg|thumb|300px|right|Immunofluorescence of <i>Cryptosporidium</i>, the microbe that caused an epidemic in Milwaukee in 1993. Over 50 deaths were credited to the waterborne microbe . Courtesy: [http://www.epa.gov/microbes/cpt_seq1.html H.D.A Lindquist (EPA)]]] | [[Image:Cryptosporidium1.jpeg|thumb|300px|right|Immunofluorescence of <i>Cryptosporidium</i>, the microbe that caused an epidemic in Milwaukee in 1993. Over 50 deaths were credited to the waterborne microbe . Courtesy: [http://www.epa.gov/microbes/cpt_seq1.html H.D.A Lindquist (EPA)]]] | ||

<i>[http://microbewiki.kenyon.edu/index.php/Cryptosporidium Cryptosporidium parvum]</i> is a type of parasite capable of causing gastrointestinal illness. Unlike <i>Helicobacter pylori</i>, however, <i>Cryptosporidium</i> has been proven to be unresponsive to most chlorination<sup> | <i>[http://microbewiki.kenyon.edu/index.php/Cryptosporidium Cryptosporidium parvum]</i> is a type of parasite capable of causing gastrointestinal illness. Unlike <i>Helicobacter pylori</i>, however, <i>Cryptosporidium</i> has been proven to be unresponsive to most chlorination<sup>8</sup>. | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

In 1993, Milwaukee (Wisconsin) experienced one of the worst waterborne outbreaks after one of the city's water plants failed to remove <i>Cryptosporidium</i> oocysts from the Lake Michigan water collected for public use. Over 403,000 residents and visitors were affected, experiencing the watery diarrhea, nausea, fever, vomiting, and abdominal cramps associated with infection. Approximately 54 deaths occurred, although there is some debate regarding other preexisting conditions that affected patient survival<sup> | In 1993, Milwaukee (Wisconsin) experienced one of the worst waterborne outbreaks after one of the city's water plants failed to remove <i>Cryptosporidium</i> oocysts from the Lake Michigan water collected for public use. Over 403,000 residents and visitors were affected, experiencing the watery diarrhea, nausea, fever, vomiting, and abdominal cramps associated with infection. Approximately 54 deaths occurred, although there is some debate regarding other preexisting conditions that affected patient survival<sup>9</sup> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

In October 2013, a resurgence of the <i>Cryptosporidium</i> protozoan appeared in Milwaukee, this time in local swimming pools<sup> | In October 2013, a resurgence of the <i>Cryptosporidium</i> protozoan appeared in Milwaukee, this time in local swimming pools<sup>10</sup>. | ||

==Methods== | ==Methods== | ||

| Line 35: | Line 35: | ||

===Quality Monitoring=== | ===Quality Monitoring=== | ||

DNA microarray can be used to monitor water quality more precisely<sup> | DNA microarray can be used to monitor water quality more precisely<sup>11</sup>. | ||

| Line 42: | Line 42: | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

<sup>1</sup> [http://www. | <sup>1</sup> [http://www.npr.org/2011/01/07/132743638/disinfectant-to-clean-water-has-problems-of-its-own "Chlorine Substitutes In Water May Have Risks". 7 January 2011. NPR.] | ||

<sup>2</sup> [http:// | <sup>2</sup> [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9336664 Rutala W., Weber D. "Uses of Inorganic Hypochlorite (Bleach) in Health-Care Facilities". 1997. Clinical Microbiology Reviews 10(4). p. 597-610.] | ||

<sup>3</sup> [http:// | <sup>3</sup> [http://water.me.vccs.edu/concepts/chlorchemistry.html "Chlorination Chemistry"] | ||

<sup>4</sup> [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ | <sup>4</sup> [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12546197 Leclerc H., Schwartzbrod L., Dei-Cas E. "Microbial agents associated with waterborne diseases". 2002. Crit Rev Microbiol 28(4). p. 371-409] | ||

<sup>5</sup> [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ | <sup>5</sup> [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1566363/pdf/envhper00518-0193.pdf Ford T. "Microbiological Safety of Drinking Water: United States and Global Perspectives". February 1999. Environmental Health Perspectives 107(1). p. 191-206] | ||

<sup>6</sup> [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/ | <sup>6</sup> [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8612990 Hulten K., Han S.W., Enroth H., Klein P.D., Opekun A.R., Gilman R.H., Evans D.G., Graham D.Y., El-Zaatari F.A. "''Helicobacter pylori'' in the drinking water in Peru". ''Gastroenterology''. April 1996. Volume 110(4). p. 1031-5.] | ||

<sup>7</sup> [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ | <sup>7</sup> [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11529557 Horiuchi T., Ohkusa T., Watanabe M., Kobayashi D., Miwa H., Eishi Y. "''Helicobacter pylori'' DNA in dirnking water in Japan". ''Microbol Immunol''. 2001. Volume 45(7). p. 515-9.] | ||

<sup>8</sup> [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/ | <sup>8</sup> [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC92099 Bukhari Z., Marshall M.M., Korich D.G., Fricker C.R., Smith H.V., Rosen J., Clancy J.L. "Effects of ozone, chlorine dioxide, chlorine, and monochloramine on Cryptosporidium parvum oocyst viability". 1990. Appl Environ Microbiol 56(5). p. 1423-8.] | ||

<sup>9</sup> [http://www. | <sup>9</sup> [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1381251/ Hoxie N.J., Davis J.P., Vergeront J.M., Blair K.A. "Cryptosporidiosis-associated mortality following a massive waterborne outbreak in Milwaukee, Wisconsin". December 1997. Am J Public Health 87(12). p. 2032-5.] | ||

<sup>10</sup> [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15490968 Lemarchand K., Masson L., Brousseau R. "Molecular biology and DNA microarray technology for microbial quality monitoring of water.". 2004. Crit Rev Microbiol 30(3). p. 145-72.] | <sup>10</sup> [http://www.jsonline.com/news/health/four-new-cases-of-crytosporidium-confirmed-b99111026z1-226013821.html Karen Herzog. "4 new cases of Cryptosporidium confirmed on North Shore". 1 October 2013. Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.] | ||

<sup>11</sup> [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15490968 Lemarchand K., Masson L., Brousseau R. "Molecular biology and DNA microarray technology for microbial quality monitoring of water.". 2004. Crit Rev Microbiol 30(3). p. 145-72.] | |||

<br>Edited by Erika Jensen, student of [mailto:slonczewski@kenyon.edu Joan Slonczewski] for [http://biology.kenyon.edu/courses/biol116/biol116_Fall_2013.html BIOL 116 Information in Living Systems], 2013, [http://www.kenyon.edu/index.xml Kenyon College]. | <br>Edited by Erika Jensen, student of [mailto:slonczewski@kenyon.edu Joan Slonczewski] for [http://biology.kenyon.edu/courses/biol116/biol116_Fall_2013.html BIOL 116 Information in Living Systems], 2013, [http://www.kenyon.edu/index.xml Kenyon College]. | ||

<!--Do not edit or remove this line-->[[Category:Pages edited by students of Joan Slonczewski at Kenyon College]] | <!--Do not edit or remove this line-->[[Category:Pages edited by students of Joan Slonczewski at Kenyon College]] | ||

Revision as of 04:52, 7 November 2013

Introduction

From swimming pools to wells, chlorine is a common chemical used to disinfect water sources. About a century ago, the process of chlorination was introduced in order to prevent the spread of diseases such as typhoid or cholera. Over time, the process has modified, with the EPA (Environmental Protection Agency) beginning to implement the use of chloramine, a closely related compound, instead1.

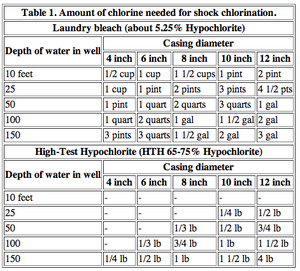

Due to safety concerns, hypochlorite (bleach) is the most commonly used compound to conduct shock chlorination2. Hypochlorite is used in one of three forms: commercial bleach (approx. 3.5-5% concentration), calcium hypochlorite (Ca(OCl)3; 65-70% concentrated), or sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl; about 12% concentration)2. These forms of hypochlorite are not as pure as chlorine gas, and will degrade in strength when in storage. However, like chlorine gas, they also react with water to form a disinfectant, hypochlorous acid (HOCl).

Microbial agents

Frequently, microbial factors infiltrate water sources through fecal matter. Many types of bacterial pathogens can initiate waterborne illnesses, including enteric bacteria, protozoa, or viruses4.

Due to the variety of species that can inhabit water sources, it comes as no surprise that chlorine has varying affects on the types of microbes. Though time and concentration can eliminate virtually every species, some species remain resistant to the process. Species such as Vibrio cholera have been tested to last approximately 30 days in drinking water sources, while toxigenic E.coli can last 90 days5. Survival techniques include cysts, spores, absorption, and intracellular survival and growth. Other species will remain viable, but no longer culturable.

Helicobacter pylori

Helicobacter pylori is known to cause gastritis and peptic ulcers.

Studies done in Peru6 and Japan7 have shown the presence of the bacteria in public water sources, proving its possibility as a waterborne microbe.

Cryptosporidium

Cryptosporidium parvum is a type of parasite capable of causing gastrointestinal illness. Unlike Helicobacter pylori, however, Cryptosporidium has been proven to be unresponsive to most chlorination8.

In 1993, Milwaukee (Wisconsin) experienced one of the worst waterborne outbreaks after one of the city's water plants failed to remove Cryptosporidium oocysts from the Lake Michigan water collected for public use. Over 403,000 residents and visitors were affected, experiencing the watery diarrhea, nausea, fever, vomiting, and abdominal cramps associated with infection. Approximately 54 deaths occurred, although there is some debate regarding other preexisting conditions that affected patient survival9

In October 2013, a resurgence of the Cryptosporidium protozoan appeared in Milwaukee, this time in local swimming pools10.

Methods

Commercial

Domestic

Success rates

Related and Alternative methods

Scientists are not content with shock chlorination. As technology advances, methods to improve both testing and disinfection are created.

Quality Monitoring

DNA microarray can be used to monitor water quality more precisely11.

Chlorine Replacements

Various groups complain about the toxic residues created by chlorination. However, various alternatives that have been created appear to have faults of their own.

References

1 "Chlorine Substitutes In Water May Have Risks". 7 January 2011. NPR.

Edited by Erika Jensen, student of Joan Slonczewski for BIOL 116 Information in Living Systems, 2013, Kenyon College.