Desulfurobacterium: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 48: | Line 48: | ||

==Genome Structure== | ==Genome Structure== | ||

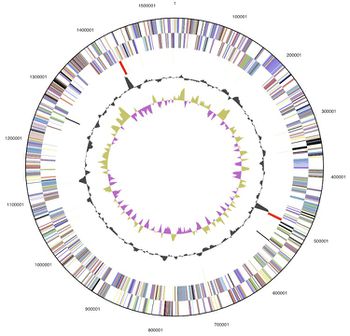

[[File:Desulfuro Genome.jpg|thumb|left| | [[File:Desulfuro Genome.jpg|thumb|left|350px|<strong>Figure 3.</strong> Graphical circular map of the genome. From bottom to top: Genes on forward strand (color by COG categories), Genes on reverse strand (color by COG categories), RNA genes (tRNAs green, rRNAs red, other RNAs black), GC content, GC skew (Göker et. al., 2011).]] | ||

<strong>Genome Size:</strong> 1 circular chromosome | <strong>Genome Size:</strong><br> | ||

1 circular chromosome<br> | |||

1.54 Mb (1,541,968 base pairs long)<br> | |||

1,594 genes<br> | |||

1,543 protein-coding regions (96.80%)<br> | |||

G+C Content= ~35%<br> | |||

--> 34 of the genes (2.13%) are also known to be pseudo genes, however 1,204 (75.53%) of the total genes have a predicted function with reasonable certainty (Göker et. al., 2011) | -->34 of the genes (2.13%) are also known to be pseudo genes, however 1,204 (75.53%) of the total genes have a predicted function with reasonable certainty (Göker et. al., 2011) | ||

<strong>Interesting Features:</strong> On the 16s rRNA sequence, between positions 198-219, there is a CUC bulge characteristic of the aquificales lineage (Göker et. al., 2011). The observation of this phenomenon has led to recent discrepancy as to which specific classification order the species should be included. | <strong>Interesting Features:</strong> On the 16s rRNA sequence, between positions 198-219, there is a CUC bulge characteristic of the aquificales lineage (Göker et. al., 2011). The observation of this phenomenon has led to recent discrepancy as to which specific classification order the species should be included. | ||

==Cell Structure, Metabolism and Life Cycle== | ==Cell Structure, Metabolism and Life Cycle== | ||

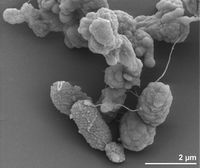

[[File:Desulfurobacterium thermolithotrophum Larger Structure.jpg|thumb|right|200px|<strong>Figure 4.</strong> Scanning electron micrograph of <var>D. thermolithotrophum</var> BSAT (Göker et. al., 2011).]] | [[File:Desulfurobacterium thermolithotrophum Larger Structure.jpg|thumb|right|200px|<strong>Figure 4.</strong> Scanning electron micrograph of <var>D. thermolithotrophum</var> BSAT (Göker et. al., 2011).]] | ||

<big><strong>Cell Structure</strong></big><br>The cells of <var>D. thermolithotrophum</var> are small and rod-shaped (bacterium - meaning non-spore producing), ranging from about 1-2 micrometers long & 0.4-0.5 micrometers wide. However, some cells can become spherical during stationary growth phase, which seems interesting since the cell desires to have the most efficient possible surface-to-volume ratio, and spherical cells are the worst at meeting this parameter (L'Haridon et. al., 1998). Though the reasons explaining this preference are not surely known, some scientists have theorized that such changes are used to combat changing environmental conditions during nutrient uptake in order to keep maximum efficiency (Young, 2006). The cells are observed to occur in either singles or in pairs as highly motile (up to 3 flagella) and containing an oblique S-Layer lattice that frequently peels off to form loops. The observed peeling, according to Sleytr & Beveridge (1999), may serve to prevent the cells from clogging further envelope layers. <var>D. thermolithotrophum</var> are Gram-negative, meaning that they can be decolorized to accept the counterstain (rather than retaining the violet dye) (L'Haridon et. al., 1998). Additionally, these results suggest a high amount of lipids & lipoproteins due to the outer membrane present. | |||

<big><strong>Metabolism & Life Cycle</strong></big><br><var>D. thermolithotrophum</var> are observed to be strict (obligate) anaerobes, meaning that they do not utilize Oxygen as an electron acceptor and are actually harmed by its presence. Instead, these organisms use Sulphur as its electron acceptor, as well as hydrogen gas (H2) as the electron donor in reducing sulfate into hydrogen sulfide gas. Aside from Sulfur, these organisms can also utilize: Thiosulfate, Sulfite, and other Polysulfides as alternative electron acceptors. However, <var>D. thermolithotrophum</var> were unable to use cysteine, sulphate (which seemed very interesting), nitrate, or nitrite in this process (L'Haridon et. al., 1998). | |||

==Ecology and Pathogenesis== | ==Ecology and Pathogenesis== | ||

| Line 74: | Line 76: | ||

3. Sievert S M, Kiene R P, Schulz-Vogt H N. The Sulfur Cycle. <var>Oceanography</var>. 2007; 20(2):117-123. | 3. Sievert S M, Kiene R P, Schulz-Vogt H N. The Sulfur Cycle. <var>Oceanography</var>. 2007; 20(2):117-123. | ||

4. Sleytr U. B., Beveridge T. J. (1999) Bacterial S-layers. Trends Microbiol. 7:253–260. | |||

5. Young KD. The Selective Value of Bacterial Shape. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 2006;70(3):660-703. | |||

==Author== | ==Author== | ||

Page authored by William Van Cleef III & Meghan Von Holt, students of Professor Jay Lennon at Indiana University Bloomington. | Page authored by William Van Cleef III & Meghan Von Holt, students of Professor Jay Lennon at Indiana University Bloomington. | ||

Revision as of 20:04, 29 April 2015

Desulfurobacterium thermolithotrophum

Classification

|

NCBI: Taxonomy |

Domain: Bacteria

Phylum: Aquificae

Class: Aquificae

Order: Desulfurobacteriales

Family: Desulfurobacteriaceae

Genus: Desulfurobacterium

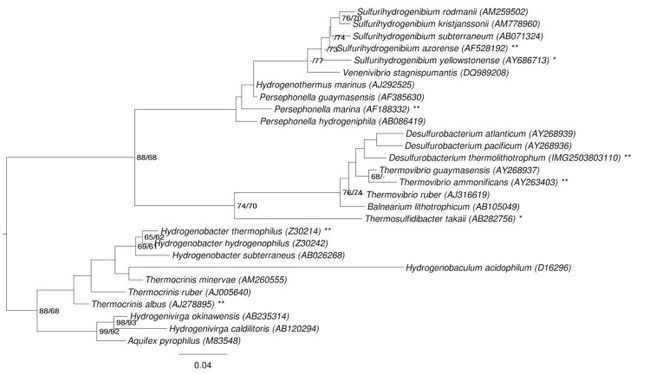

--> Recent discrepancy amongst scientists of whether or not this organism belongs to the Order of Aquificales or Desulfurobacteriales (Göker et. al., 2011).

Species

Desulfurobacterium thermolithotrophum

Related Species:

Desulfurobacterium atlanticum, Desulfurobacterium crinifex, Desulfurobacterium pacificum

Description and Significance

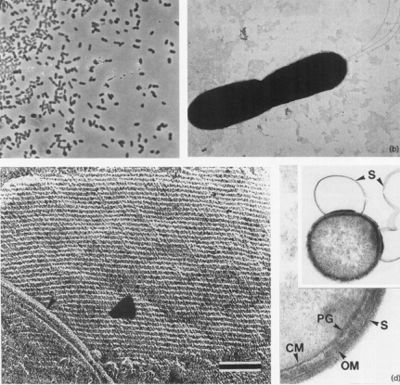

Appearance:

Cells appear as small rods, about 1-2 µm long and 0.4-0.5 µm wide (seen in Figure 2a and b) and are stained as Gram-negative. These cells can occur either singly or in pairs, and are observed to be highly motile. Through negative staining, up to three flagella could be observed under a microscope. Moreover, during the stationary growth phase, some rods become spherical (L'Haridon et. al., 1998).

Habitat:

Desulfurobacterium thermolithotrophum are anaerobic chemolithoautotrophs, typically found in hot, deep-sea hydrothermal vents, such as the Snake Pit vent field of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. These thermophiles are capable of survival in temperatures ranging from 40°-75°C, but prefer an optimal temperature of 70°C. In addition to a tolerance to a variety of temperatures, this strain has also been observed (in vitro) to survive in conditions ranging from a pH of 4.4-8.0, with an optimal pH level of 6.0. A medium of salt concentration 35 g/L would be most preferred by this species for cultivation, yet a range of 15-70 g/L would also be suitable for growth. Given these optimal conditions are met, the experimentally observed doubling time was ~135 minutes (L'Haridon et. al., 1998).

Significance:

Most extremely thermophilic microorganisms that are found in deep-sea hydrothermal vents are archaea species. However, Desulfurobacterium thermolithotrophum is the first bacteria capable of serving as a primary producer in such an environmental conditions (L'Haridon et. al., 1998).

Genome Structure

Genome Size:

1 circular chromosome

1.54 Mb (1,541,968 base pairs long)

1,594 genes

1,543 protein-coding regions (96.80%)

G+C Content= ~35%

-->34 of the genes (2.13%) are also known to be pseudo genes, however 1,204 (75.53%) of the total genes have a predicted function with reasonable certainty (Göker et. al., 2011)

Interesting Features: On the 16s rRNA sequence, between positions 198-219, there is a CUC bulge characteristic of the aquificales lineage (Göker et. al., 2011). The observation of this phenomenon has led to recent discrepancy as to which specific classification order the species should be included.

Cell Structure, Metabolism and Life Cycle

Cell Structure

The cells of D. thermolithotrophum are small and rod-shaped (bacterium - meaning non-spore producing), ranging from about 1-2 micrometers long & 0.4-0.5 micrometers wide. However, some cells can become spherical during stationary growth phase, which seems interesting since the cell desires to have the most efficient possible surface-to-volume ratio, and spherical cells are the worst at meeting this parameter (L'Haridon et. al., 1998). Though the reasons explaining this preference are not surely known, some scientists have theorized that such changes are used to combat changing environmental conditions during nutrient uptake in order to keep maximum efficiency (Young, 2006). The cells are observed to occur in either singles or in pairs as highly motile (up to 3 flagella) and containing an oblique S-Layer lattice that frequently peels off to form loops. The observed peeling, according to Sleytr & Beveridge (1999), may serve to prevent the cells from clogging further envelope layers. D. thermolithotrophum are Gram-negative, meaning that they can be decolorized to accept the counterstain (rather than retaining the violet dye) (L'Haridon et. al., 1998). Additionally, these results suggest a high amount of lipids & lipoproteins due to the outer membrane present.

Metabolism & Life Cycle

D. thermolithotrophum are observed to be strict (obligate) anaerobes, meaning that they do not utilize Oxygen as an electron acceptor and are actually harmed by its presence. Instead, these organisms use Sulphur as its electron acceptor, as well as hydrogen gas (H2) as the electron donor in reducing sulfate into hydrogen sulfide gas. Aside from Sulfur, these organisms can also utilize: Thiosulfate, Sulfite, and other Polysulfides as alternative electron acceptors. However, D. thermolithotrophum were unable to use cysteine, sulphate (which seemed very interesting), nitrate, or nitrite in this process (L'Haridon et. al., 1998).

Ecology and Pathogenesis

Habitat; symbiosis; biogeochemical significance; contributions to environment.

If relevant, how does this organism cause disease? Human, animal, plant hosts? Virulence factors, as well as patient symptoms.

References

1. L'Haridon S, Cilia V, Messner P, Raguénès G, Gambacorta A, Sleytr UB, Prieur D, Jeanthon C. Desulfurobacterium thermolithotrophum gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel autotrophic, sulphur-reducing bacterium isolated from a deep-sea hydrothermal vent. International Journal of Systematic Bacteriology , 1998; 48:701-711. PubMed

2. Göker M, Daligault H, Mwirichia R, et al. Complete genome sequence of the thermophilic sulfur-reducer Desulfurobacterium thermolithotrophum type strain (BSAT) from a deep-sea hydrothermal vent. Standards in Genomic Sciences. 2011;5(3):407-415. PubMed

3. Sievert S M, Kiene R P, Schulz-Vogt H N. The Sulfur Cycle. Oceanography. 2007; 20(2):117-123.

4. Sleytr U. B., Beveridge T. J. (1999) Bacterial S-layers. Trends Microbiol. 7:253–260.

5. Young KD. The Selective Value of Bacterial Shape. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 2006;70(3):660-703.

Author

Page authored by William Van Cleef III & Meghan Von Holt, students of Professor Jay Lennon at Indiana University Bloomington.