Pelagibacterales (SAR11): Difference between revisions

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

The order was originally named SAR11 following its discovery in the Sargasso Sea in 1990 by Professor Stephen Giovannoni and colleagues, from Oregon State University.(2)(5) It was first placed in the order of Rickettsiales, but after rRNA gene-based phyogenetic analysis in 2013, it was raised to the rank of order, and then placed as sister order to the Rickettsiales in the subclass Rickettsidae.(5) | The order was originally named SAR11 following its discovery in the Sargasso Sea in 1990 by Professor Stephen Giovannoni and colleagues, from Oregon State University.(2)(5) It was first placed in the order of Rickettsiales, but after rRNA gene-based phyogenetic analysis in 2013, it was raised to the rank of order, and then placed as sister order to the Rickettsiales in the subclass Rickettsidae.(5) | ||

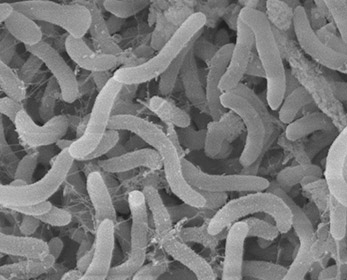

These rod shaped organisms are one of the smallest free cells known. With a cell volume less than 1/500th the volume of E.coli, they have a high surface to volume ratio for absorbing nutrients | These gram negative rod shaped organisms are one of the smallest free cells known with the smallest known genomes. With a cell volume less than 1/500th the volume of E.coli, they have a high surface to volume ratio for absorbing nutrients. 30% of the cell's volume is taken up by its genome.(7) Despite the small genome, Pelagibacterales have the complete biosynthetic pathways for all 20 amino acids and all but a few cofactors. There are no pseudogenes, introns, transposons, or extrachromosomal elements yet observed for any cell. | ||

Pelagibacterales | |||

==Genome Structure== | ==Genome Structure== | ||

Revision as of 08:54, 15 May 2015

Classification

Domain: Bacteria

Phylum: Proteobacteria

Class: Alphaproteobacteria

Subclass: Rickettsidae

Order: Pelagibacterales

Description and Significance

Pelagibacterales (SAR11) is an order in the Alphaproteobacteria composed of free-living planktonic oligotrophic facultative photochemotroph bacteria. (4)(5) They are most abundant group of planktonic cells in marine systems and possibly the most numerous bacterium in the world. Typically accounting for ~25% of prokaryotic cells in seawater worldwide.(3) The order was originally named SAR11 following its discovery in the Sargasso Sea in 1990 by Professor Stephen Giovannoni and colleagues, from Oregon State University.(2)(5) It was first placed in the order of Rickettsiales, but after rRNA gene-based phyogenetic analysis in 2013, it was raised to the rank of order, and then placed as sister order to the Rickettsiales in the subclass Rickettsidae.(5)

These gram negative rod shaped organisms are one of the smallest free cells known with the smallest known genomes. With a cell volume less than 1/500th the volume of E.coli, they have a high surface to volume ratio for absorbing nutrients. 30% of the cell's volume is taken up by its genome.(7) Despite the small genome, Pelagibacterales have the complete biosynthetic pathways for all 20 amino acids and all but a few cofactors. There are no pseudogenes, introns, transposons, or extrachromosomal elements yet observed for any cell.

Genome Structure

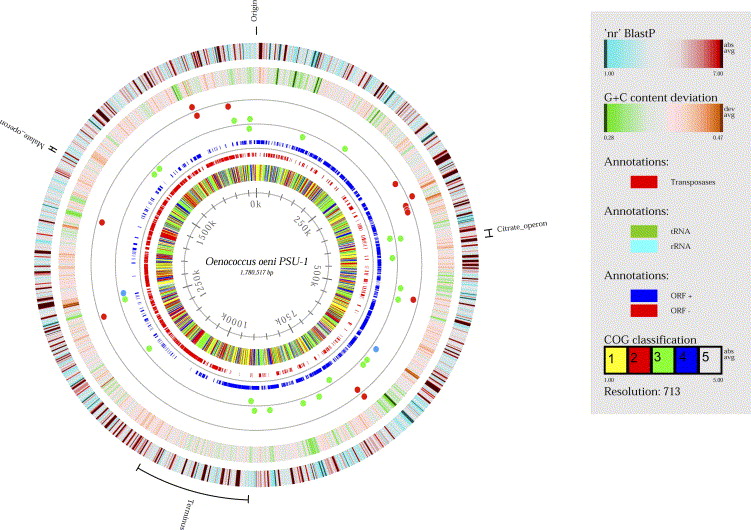

An industrial standard strain of O. oeni, PSU-1, has a circular genome of 1780517 basepair nucleotides, 1691 protein-coding genes, and 51 RNA genes (7). 43 tRNA sequences that represent 20 amino acids and 14 different insertion sequence transposase genes are present. Comparing different strains of O. oeni genomes, the general number of nucleotides tends to be very similar across the specie (7). The critical malolactic fermentation operates from the mleA gene, coding for the malolactic enzyme that breaks down the malic acid in the environment. Morphological and genomic evidence established the grounds to reclassify this bacteria as Oenococcus oeni.

Cell Structure, Metabolism and Life Cycle

Oenococcus oeni is a facultative anaerobe. It is able to use oxygen for cellular respiration but can also gain energy through fermentation. It characteristically grows well in the environments of wine, being able to survive in acidic conditions below pH 3.0 and tolerant of ethanol levels above 10% (2). Optimal growth occurs on sugar and protein rich media, like grape or tomato juice. The cocci are ellipsoidal to spherical in shape, usually grow in chains or pairs, and are typically non-sporulating. Lactic acid bacteria, like Oenococcus oeni, perform malolactic fermentation (also known as malolatic conversion). It occurs after (or sometimes during) primary fermentation. The main function of malolatic fermentation is converting glucose and malic acid to lactic acid. This is occurs by the uptake of malate, decarboxylation of malate to L-lactic acid and carbon dioxide, and the export of end products. O. oeni is heterofermentative, meaning it can create multiple end products from fermenting the sugars. In O. oeni’s case, it produces carbon dioxide, ethanol, and acetate, as well as characteristic flavor molecules like diacetyl. Strain variation of Oenoccocus oeni cellular processes can have significant effects on the community dynamics, fermentation, and overall quality of wine. Strain variation exists in sugar utilization pathways, phosphototransferase enzyme II systems, bacteriophage integration, and cell wall exopolysaccharides (3).

Ecology

Oenococcus oeni stabilizes wine communities by consuming available nutrients and lowering potential growth of other microbes, but its malolactic fermentation can be beneficial or detrimental to the production of wine depending on grapes, climate, and style of wine. Variations between strains and fermentation conditions have the potential to impact general quality and production of wine. Industrial winemakers use a standardized strain of O. oeni, but the many external and environmental variables will dictate the success of the wine. O. oeni is not the only lactic acid bacteria that can perform secondary fermentation. There are a variety of lactic acid bacteria that can dominate bacterial community in response to temperature, nutrients, sulfur dioxide content, pH, ethanol levels, and inoculation densities. O. oeni commonly dominates secondary fermentation from its extreme tolerance to pH and ethanol levels. The molecule diacetyl is produced as a byproduct of lactic acid bacteria in secondary fermentation. In wine, the levels of diacetyl create buttery and caramel flavor notes. It is generated when there is little or no malic acid to be consumed so citric acid is used. This byproduct is sought out by some winemakers while it is avoided by others. Rarely do the diacetyl levels reach a point of spoiling the wine (10).

Because of its heterofermentive properties, Oenoccocus may be viewed as an ecosystem engineer. O. oeni plays a major role in establishing the environment for which other microbes will interact. Its end products and life strategies positively feedback into creating a more harsh environment for other microbes like yeasts and fungi while making the conditions more ideal for other lactic acid bacteria (5).

References

(1) "Rebounding bacteria". 2013

(2) “SAR11 bacteria thrive — despite viruses”.“Nature”

(6) A war without end - with Earth’s carbon cycle held in the balance

(9) phys.org “Raise your glass to Oenococcus oeni, a real wine bug”. “Science X Network”. 2014.

Author

Page authored by Digvinder Singh Mavi student of Prof. Katherine Mcmahon at University of Wisconsin-Madison.