Polysphondylium pallidum: Difference between revisions

| Line 19: | Line 19: | ||

''P. pallidum'' is a cellular slime mold of the phylum Mycetozoa. It begins its life as a single-celled amoeboid protist and lives in feces, soil, and other organic matter [[#References|[1]]]. Like other cellular slime molds, ''P. pallidum'' can reproduce both sexually and asexually depending on its environmental conditions [[#References|[1]]] and has two distinct stages of its life cycle: a vegetative non-social stage and an aggregate phase which is cued by starvation [[#References|[5]]]. | ''P. pallidum'' is a cellular slime mold of the phylum Mycetozoa. It begins its life as a single-celled amoeboid protist and lives in feces, soil, and other organic matter [[#References|[1]]]. Like other cellular slime molds, ''P. pallidum'' can reproduce both sexually and asexually depending on its environmental conditions [[#References|[1]]] and has two distinct stages of its life cycle: a sexual vegetative non-social stage and an asexual aggregate phase which is cued by starvation [[#References|[5]]]. | ||

Revision as of 12:05, 25 April 2017

Classification

Domain; Phylum; Class; Order; family [Others may be used. Use NCBI link to find]

Species

|

NCBI: Taxonomy |

Genus species

Description and Significance

Polysphondylium pallidum was first described by Edgar W. Olive in 1901 as growing on the dung of a donkey, muskrat, and rabbit in Liberia [2,4].

P. pallidum is a cellular slime mold of the phylum Mycetozoa. It begins its life as a single-celled amoeboid protist and lives in feces, soil, and other organic matter [1]. Like other cellular slime molds, P. pallidum can reproduce both sexually and asexually depending on its environmental conditions [1] and has two distinct stages of its life cycle: a sexual vegetative non-social stage and an asexual aggregate phase which is cued by starvation [5].

Biologists have been particularly interested in cellular slime molds because their asexual cycles model cell differentiation in eukaryotes [2,3]. With their simple and easy-to-manipulate systems, cellular slime molds provide insight into the formation of multicellular organisms [2]. P. pallidum in particular has been used a variety of experiments because of its high levels of germination compared to other sexually reproducing slime molds, making it useful for studies of transmission patterns [3].

Genome Structure

P. pallidum is predicted to contain seven linear chromosomes during the sexual, haploid stage of its lifecycle. The total genome size of these seven chromosomes is about 33Mbp, representing 12.3k coding sequences with an average gene length of 1.6kb, 32% G/C content, and a telomeric repeat sequence of TAAGGG. (2) P. pallidum is also predicted to contain a 48kb mitochrondrial genome. (2) Additionally the PPN500 strain of P. pallidum, which is commonly used in research, contains a 27kb circular plasmid with 11 predicted coding sequences. (3)

P. pallidum is predicted to have diverged alongside Dictyostelium discoideum and Dictyostelium fasciculatum from a recent common ancestor about 0.6 billion years ago. (2) The P. pallidum genome contains comparably fewer transposable elements and shows high conservation of genes related primary metabolism, cytoskeletal function, and signal transduction compared to other Dictyosteliidae. Notable proteins that have been predicted in P. pallidum include polyketide synthases, which can be used to produce antibiotics and fungicides from secondary metabolites; calcium-dependent cell-adhesion proteins, which allow for extracellular cell adhesion; LagBC homologs, which are used for kin discrimination in D. discoideum; and cAMP/cGMP adenylyl cyclases ACA, ACB, ACG, sGC, and GCA. (2) cAMP and cGMP in Dictyosteliidae are secreted as signalling molecules during chemotactic cell aggregation.

Cell Structure, Metabolism and Life Cycle

Interesting features of cell structure; how it gains energy; what important molecules it produces.

Ecology and Pathogenesis

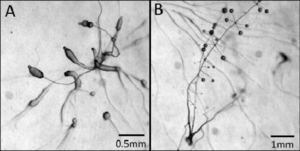

Polysphondylium pallidum, like other cellular slime molds, can be found world-wide living in soil, dung, leaf litter, and other decaying organic matter often found in forests and caves [1,12,13]. It spends the majority of its life feeding on bacteria as an independent amoeboid unicellular protist, acting in forest soils to maintain the balance of microbial flora [11]. In the absence of sufficient bacterial food, a starvation-induced chemical signal is emitted, causing the the individual cells to aggregate [10]. The assemblage of cells act as a single multicellular mass of approximately 100,000 cells which can move to an appropriate location and create a fruiting body [10].

Interestingly, Polysphondylium pallidum was the first recorded cellular slime mold seen to kill other slime molds [12]. The unique P. pallidum strain CK-8 isolated from Japanese forest soils was found to kill all nearby strains of Dictyostelium and Polysphondylium except for a single resistant strain (CK-9) isolated from soils very near to CK-8, found to be the same mating type as strain CK-8. As such, the CK-8 strain of P. pallidum may have a competitive advantage in nature with the ability to outcompete and kill other slime molds of differing mating types [12].

References

- Encyclopedia of Life: Polysphondylium pallidum

- University of Califronia: Introduction to Slime Molds

- Mirfakhrai, M., Tanaka, Y., & Yanagisawa, K. (1990). Evidence for mitochondrial DNA polymorphism and uniparental inheritance in the cellular slime mold Polysphondylium pallidum: effect of intraspecies mating on mitochondrial DNA transmission. Genetics, 124(3), 607-613.

- Olive, Edgar W. (1901). "A preliminary enumeration of the Sorophoreae". Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences 37 (12): 333–344. doi:10.2307/20021671.

- Rosen, S. D., Simpson, D. L., Rose, J. E., & Barondes, S. H. (1974). Carbohydrate-binding protein from Polysphondylium pallidum implicated in intercellular adhesion. Nature, 252(5479), 128-151.

- DictyBase

- Heidel AJ, Lawal HM, Felder M, Schilde C, Helps NR, et al. 2011. Phylogeny-wide analysis of social amoeba genomes highlights ancient origins for complex intercellular communication. Genome Research 21:1882-1891

- European Nucleotide Archive

- New World Encyclopedia

- Dela Cruz, T. E. E., Santiago, K. A. A., Ramirez, C. S. P., Torres, J. M. O., Dagamac, N. H. A., Yap, J., ... & Yulo, P. R. J. (2011). Occurrence of Cellular Slime Molds (Dictyostelids) in Subic Bay Natural Forest Reserve, Zambales, Philippines. Philippine Journal of Systematic Biology, 5, 99-104.

- Mizutani, A., Hagiwara, H., & Yanagisawa, K. (1990). A killer factor produced by the cellular slime mold Polysphondylium pallidum. Archives of microbiology, 153(5), 413-416.

- Landolt, J. C., Stephenson, S. L., & Slay, M. E. (2006). Dictyostelid cellular slime molds from caves. J Cave Karst Stud, 68, 22-26.

Author

Page authored by Benjamin Braude and Alexandra Canzoneri, students of Prof. Jay Lennon at Indiana University.