Geosiphon-Nostoc Endosymbiosis: Difference between revisions

| Line 36: | Line 36: | ||

=Ecology and Symbiosis= | =Ecology and Symbiosis= | ||

[[File:geopyr symbiosis.png|thumbnail|500px|Geosiphon-Nostoc symbiosis (Schubler et al., 2012)]] | [[File:geopyr symbiosis.png|thumbnail|500px|Geosiphon-Nostoc symbiosis (Schubler et al., 2012)]] | ||

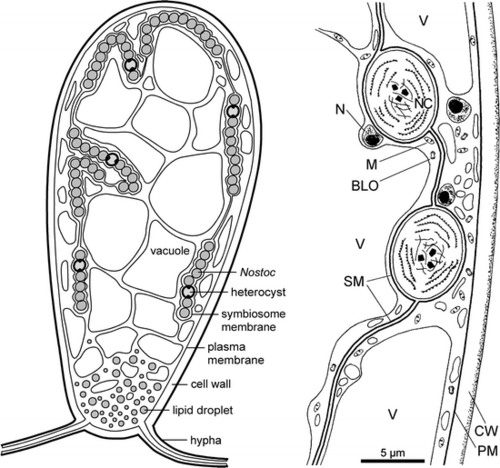

As opposed to other AMF, which penetrate the plant cells to form arbuscules, G. pyriformis forms long fungal cells (‘bladders’) that enclose cyanobacteria, these bladder membranes are an extension of the fungal plasma membrane. Once the fungi have trapped the cyanobacteria in their bladders, the fungus supplies the cyanobacteria with water and inorganic nutrients while the | As opposed to other AMF, which penetrate the plant cells to form arbuscules, G. pyriformis forms long fungal cells (‘bladders’) that enclose cyanobacteria, these bladder membranes are an extension of the fungal plasma membrane. Once the fungi have trapped the cyanobacteria in their bladders, the fungus supplies the cyanobacteria with water and inorganic nutrients while the cyanobacterium remains photosynthetically active and retains its ability to fix nitrogen using heterocysts. Findings also suggested that “during the switch from regular AMS to a fungal-cyanobacteria symbiosis, G. pyriformis evolved novel strategies to utilize lipids from its new host through the expansion of specific gene motifs. Specifically, the G. pyriformis genome carries a striking over-representation of lipase 3 protein domains that hydrolyze ester linkages of fatty acids. As Nostoc spp. are known to produce a wide variety of extracellular lipids in high amounts, it is possible that these abundant lipids are released in the environment (like many other cellular compounds released by cyanobacteria) and are then broken down by lipases to be used as an energy resource by G. pyriformis.” (Malar et al. 2021). | ||

=References= | =References= | ||

Revision as of 15:37, 24 April 2023

Classification

Higher order taxa

Domain: Bacteria, Phylum: Cyanobacteria, Class: Cyanophyceae, Order: Nostocales, Family: Nostocaceae, Genus: Nostoc

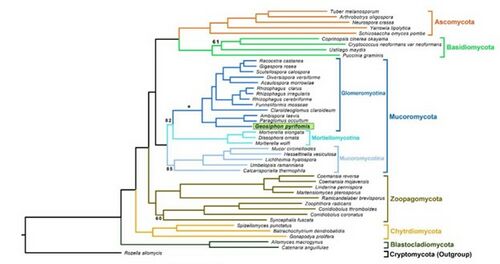

Domain: Fungi, Phylum: Mucoromycota, Class: Glomeromycetes, Order: Archaeosporales, Family: Geosiphonaceae, Genus: Geosiphon

Species

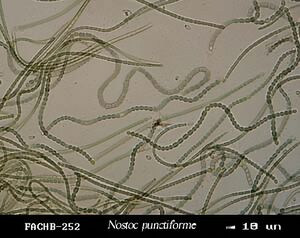

Nostoc punctiforme (ATTC 29133) Geosiphon pyriformis (NCBI 50956)

Description and significance

Nostoc punctiforme is a filamentous cyanobacterium that can be photoautotrophic, diazotrophic, heterotrophic, and/or symbiotic. It is broadly symbiotic, forming relationships with fungi, bryophytes, gymnosperms, and angiosperms. Its genome contains a large number of unique genes that likely play essential roles in cell differentiation and symbiosis (Meeks et al., 2001).

Geosiphon pyriformis is a fungus in the class Glomeromycetes, these fungi usually form arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiotic relationships with plants and cannot live without a symbiotic partner. Geosiphon pyriformis is the only fungus known form an endosymbiotic relationship with nitrogen-fixing cyanobacteria (Nostoc punctiforme). Microbiologists studying this relationship say that G. pyriformis represents an ideal candidate to investigate the origin of AMS (arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis) and the emergence of a unique endosymbiosis. (Malar et al., 2021).

16S Ribosomal RNA Gene Information

The genome of N. punctiforme is 9.5Mb, 41.5%GC, 7432 open reading frames, determined by shotgun sequencing, “A significant part of the information of a genome resides outside of genes. Protein binding sites may determine the regulation of gene transcription and the compact structure of the genome within the cell. The modification state of DNA may regulate the replication of the genome and aid in DNA repair. Transposable elements and repeated sequences may increase the plasticity of the genome and contribute to rapid changes over evolutionary time. In each of these regards, the genome of N. punctiforme is strikingly different from those of most bacteria.” (Meeks et al., 2001).

The Geosiphon pyriformis genome sequence and modeling was performed by Nicolas Corradi and Mathu Malar C at the University of Ottawa. It was determined that the genome was 128.32 Mbp with 24,195 genes, and had a GC% of 29.25. These scientists found that, in the genome, 365 genes represented putative secreted proteins, and 27% of those were candidate effectors (chemicals that aid in the initiation and maintenance of symbiosis). The researchers also looked for evidence of horizontal gene transfer between the two species and found 18 genes with bacterial potential and two protein encoding genes with significant sequence conservation with Nostoc or Gamma proteobacteria homologs (Malar et al., 2021).

Ecology and Symbiosis

As opposed to other AMF, which penetrate the plant cells to form arbuscules, G. pyriformis forms long fungal cells (‘bladders’) that enclose cyanobacteria, these bladder membranes are an extension of the fungal plasma membrane. Once the fungi have trapped the cyanobacteria in their bladders, the fungus supplies the cyanobacteria with water and inorganic nutrients while the cyanobacterium remains photosynthetically active and retains its ability to fix nitrogen using heterocysts. Findings also suggested that “during the switch from regular AMS to a fungal-cyanobacteria symbiosis, G. pyriformis evolved novel strategies to utilize lipids from its new host through the expansion of specific gene motifs. Specifically, the G. pyriformis genome carries a striking over-representation of lipase 3 protein domains that hydrolyze ester linkages of fatty acids. As Nostoc spp. are known to produce a wide variety of extracellular lipids in high amounts, it is possible that these abundant lipids are released in the environment (like many other cellular compounds released by cyanobacteria) and are then broken down by lipases to be used as an energy resource by G. pyriformis.” (Malar et al. 2021).

References

Malar C, M., Krüger, M., Krüger, C., Wang, Y., Stajich, J. E., Keller, J., Chen, E. C. H., Yildirir, G., Villeneuve-Laroche, M., Roux, C., Delaux, P.-M., & Corradi, N. (2021). The genome of Geosiphon pyriformis reveals ancestral traits linked to the emergence of the arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. Current Biology, 31(7). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2021.01.058

Meeks, J. C. (2001). An overview of the genome of Nostoc punctiforme, a multicellular, symbiotic cyanobacterium. Photosynthesis Research. https://doi.org/10.2172/841015

Schüßler, A. (2012). 5 the Geosiphon–nostoc endosymbiosis and its role as a model for arbuscular mycorrhiza research. Fungal Associations, 77–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-30826-0_5

Author

Logan Meadors