User:Newman5: Difference between revisions

| Line 30: | Line 30: | ||

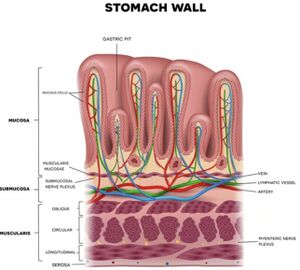

[[Image:Stomachlayers.jpg|thumb|300px|right|The epithelial cell layer acts as a chemical barrier from the pathogens that could enter the mucosa and deeper tissue and cause infection. Photo credit:[https://www.shutterstock.com/search/human-stomach-histology]]]. | [[Image:Stomachlayers.jpg|thumb|300px|right|The epithelial cell layer acts as a chemical barrier from the pathogens that could enter the mucosa and deeper tissue and cause infection. Photo credit:[https://www.shutterstock.com/search/human-stomach-histology]]]. | ||

The risk of <i>H. pylori</i> infection significantly increases when combined with aspirin, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and/or frequent steroid use. These medications compromise the stomach's epithelial barrier, creating a more favorable environment conducive to <i>H. pylori</i> colonization and persistence. Once the bacteria breach this barrier and infiltrate the gastric mucosa, the risk of developing complications like ulcers and long-term gastric cancer escalates.[https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5295741/#b19-mjms-22-5-070] | The risk of <i>H. pylori</i> infection significantly increases when combined with aspirin, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and/or frequent steroid use. These medications compromise the stomach's epithelial barrier, creating a more favorable environment conducive to <i>H. pylori</i> colonization and persistence. Once the bacteria breach this barrier and infiltrate the gastric mucosa, the risk of developing complications like ulcers and long-term gastric cancer escalates.[https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5295741/#b19-mjms-22-5-070] | ||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

==<b>Life cycle and survival mechanisms of <i>Helicobacter pylori</i></b>== | ==<b>Life cycle and survival mechanisms of <i>Helicobacter pylori</i></b>== | ||

Revision as of 17:05, 13 April 2024

The Cause of Gastric Cancer

By Alexis Newman

.

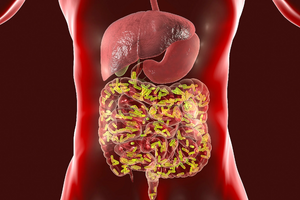

The human gut microbiome is a critical indicator of a person's health because of its profound influence on physiological processes. The number of bacterial cells outnumbers the number of human cells in the gut microbiota, and these microbes play large roles in metabolism and immune function to keep the body alive.[8] The gut microbiome also serves as a barrier against pathogens, preventing their colonization and mitigating the risk of infections. However, disruption in the gut microbiota composition or function can weaken this barrier, increasing the susceptibility to pathogen invasion and potentially leading to gastrointestinal infections.[9]

Helicobacter pylori is a gram-negative, flagella-bearing spiral-shaped proteobacterium1 that can grow in extremely acidic environments, like the stomach. Its "Helico-" name derives from its helical body and because of its shape, the bacteria can make its way through the viscous lining of the stomach with help from stomach enzymes. However, once H. pylori gets colonized in the stomach, its shape can convert from the rod shape to an inactive coccoid shape.[10]

Helicobacter pylori is a class 1 carcinogenic bacteria, 1 being named the most carcinogenic a microbe can be and 4 being non-carcinogenic. H. pylori was determined to be a class 1 carcinogen more than 30 years ago from purely epidemiological data. This investigation showed a positive relationship between gastritis cancer and H. pylori. A couple of years after this phenomenon, in 1991, further evidence showed the prevalence of H. pylori antibodies in patients with gastric and bowel cancer.[11]

.

Interstingly, H. pylori prevalence is not a problem for all hosts, in fact, some people will go their whole lives with no effects.[12]. However, for the 20 - 30% of people who are infected, the consequences can be life-threatening: gastritis (stomach cancer), peptic ulcers, and gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma. Investigation reports state that at least 7 million cases of these listed diseases happen annually, worldwide[13]

Who is at risk?

In the United States, age emerges as a significant determinant of H. pylori infection, with over half of infected individuals aged 50 and above. Moreover, disparities in genetics and health further exacerbate the prevalence of the infection among African Americans, with around half of Latin American and Eastern European descent also affected by H. pylori.[14]

.

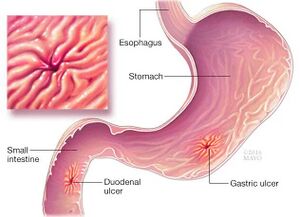

The risk of H. pylori infection significantly increases when combined with aspirin, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and/or frequent steroid use. These medications compromise the stomach's epithelial barrier, creating a more favorable environment conducive to H. pylori colonization and persistence. Once the bacteria breach this barrier and infiltrate the gastric mucosa, the risk of developing complications like ulcers and long-term gastric cancer escalates.[15]

Life cycle and survival mechanisms of Helicobacter pylori

.

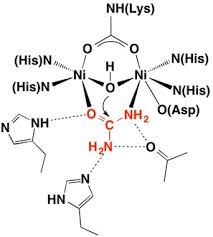

Once H. pylori makes its way into the host successfully, for it to survive and colonize the bacteria needs the means to survive in the highly acidic environment of the stomach. H. pylori secretes urease to neutralize the acidic condition and allow the bacteria to persist in the stomach.[16] The production of urease catalyzes the hydrolysis of urea into ammonia and carbon dioxide. Ammonia acts as a base to neutralize the surrounding pH of the bacteria's space. The neutralizing of this barrier allows H. pylori to use its flagella-mediated motility to adhere to epithelial cells and begin to colonize and infect the host.[17]

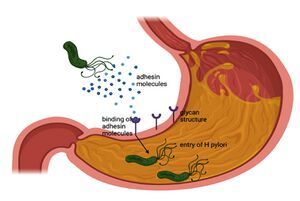

The attachment mechanisms are facilitated by the bacterial adhesions to very specific host cell receptors such as glycan receptors (BabA and SabA), membrane protein (HopZ), the specific luminal side of gastric epithelial cells (CD74), and Decat Accelerating Factor (DAF and CD55) receptors. Additionally, H. pylori can bind to sulfated molecules like herapan sulfate found on the surface of the epithelium. [18]

This immune response results in a congregation of neutrophils along with macrophages and lymphocytes all in an effort to rid the pathogen's survival and infection; however, this often does more harm than good to the host. The build-up of these immune cells causes tissue damage that creates gastric ulcers and/or more severe gastrointestinal infections.[19]

The insertion code consists of:

Double brackets: [[

Filename: Paeruginosa.webp

Thumbnail status: |thumb|

Pixel size: |300px|

Placement on page: |right|

Legend/credit: Magnified 20,000X, this colorized scanning electron micrograph (SEM) depicts a grouping of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bacteria. Photo credit: CDC. Every image requires a link to the source.

Closed double brackets: ]]

Other examples:

Bold

Italic

Subscript: H2O

Superscript: Fe3+

Sample citations: [1]

[2]

A citation code consists of a hyperlinked reference within "ref" begin and end codes.

To repeat the citation for other statements, the reference needs to have a names: "<ref name=aa>"

The repeated citation works like this, with a forward slash.[1]