Horseshoe Crab: the living fossil: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 30: | Line 30: | ||

==Conclusion== | ==Conclusion== | ||

While horseshoe crabs no longer possess the range and diversity of former times, their continued existence and survival for nearly 500 million years invite nothing short of marvel and wonder. Yet, their evolutionary success is constantly threatened by human actions. We must become aware as soon as possible of the indispensability of these fascinating creatures, not just to ourselves but also the global ecosystems, and adopt sustainable practices to sustain their survival. | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

Revision as of 16:39, 13 December 2024

Introduction

Witness to almost 500 million years of Earth's history, horseshoe crabs are the textbook definition of living fossils. Their alien-like primitive forms, featuring the iconic spine-like telson and horseshoe-shaped carapace, have remained virtually unchanged across their existence. While their resemblance to a horseshoe is difficult to challenge, “crab” is a misnomer for the creatures considering they are not even crustaceans. They are, in fact, more closely related to spiders and scorpions.

Present-day horseshoe crabs are all marine dwellers although forays into freshwater have been noted among long extinct groups. The mangrove horseshoe crab, at odds with the other three extant species, also inhabits the brackish waters found near mangrove forests.

Phylogeny and Evolution

Modern-day horseshoe crabs are chelicerate arthropods of the Limulidae family. Despite their name, they are not crustaceans at all and are, in fact, more closely related to arachnids. Of 88 formally described species, only 4 remain today and are the only surviving members of the order Xiphosura. The extant species include the Atlantic horseshoe crab Limulus polyphemus, and three Asiatic species: the Indo-Pacific horseshoe crab Tachypleus gigas, the tri-spine horseshoe crab Tachypleus tridentatus, and the mangrove horseshoe crab Carcinoscorpius rotundicauda.

Xiphosurans were considered to have first emerged in the Late Ordovician period of the Paleozoic era, some 450 million years, following the discovery and characterization of the Lunataspis aurora fossil in Canada back in 2007.[2] However, yet undescribed fossils from Morocco, discovered in 2010, established a deeper origin for the Xiphosurans, about 470 million years ago in the Lower Ordovician period of the Paleozoic era.[3] The Limulids, the family of modern horseshoe crabs, first appeared around 250 years ago in the Triassic period. Strikingly, none of the modern species has left a fossil record thus far.[4] Horseshoe crabs are commonly dubbed living fossils owing to the little morphological variation they have undergone across their existence, a phenomenon called evolutionary stasis. Two rounds of evolutionary stasis have been identified in the Xiphosurans, the conservation of prosomal and opisthosomal growth rates near their origin in the Lower Ordivician and the conservation of shape in the Jurassic period owing to the emergence of the Limulids in the Triassic. Notwithstanding physiological changes, present-day crabs are larger in size than their ancestral counterparts and have their abdominal segments fused together.[5]

Morphology

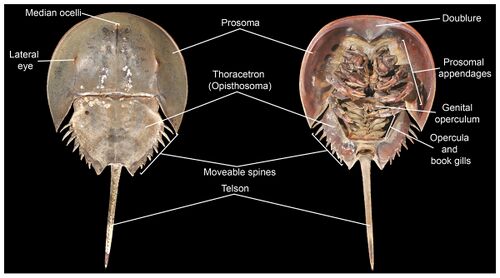

All horseshoe crabs share the same body plan: the cephalothorax or prosoma (head and chest fused together), the opisthosoma (the abdomen with the inclusion of the heart and respiratory organs, a distinctive feature of the chelicerates) and, the iconic feature of the horseshoe crab, the telson (the long tail-like spine jutting out from the abdomen). The prosoma is shrouded in a protective carapace bearing an uncanny resemblance to a horseshoe, giving the horseshoe crab its name. Unlike any other extant chelicerate, horseshoe crabs possess, among its ten eyes, two compound eyes that sit atop its carapace; they also have the largest rod and cone cells of any known animal.

Here we cite April Murphy's paper on microbiomes of the Kokosing river. [6]

Microbiome

Include some current research, with a second image.

Here we cite Murphy's microbiome research again.[6]

Conclusion

While horseshoe crabs no longer possess the range and diversity of former times, their continued existence and survival for nearly 500 million years invite nothing short of marvel and wonder. Yet, their evolutionary success is constantly threatened by human actions. We must become aware as soon as possible of the indispensability of these fascinating creatures, not just to ourselves but also the global ecosystems, and adopt sustainable practices to sustain their survival.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Lamsdell JC. The phylogeny and systematics of Xiphosura. PeerJ. 2020 Dec 4;8:e10431.

- ↑ Rudkin DM, Young GA, Nowlan GS. The oldest horseshoe crab: a new xiphosurid from Late Ordovician Konservat‐Lagerstätten deposits, Manitoba, Canada. Palaeontology. 2008 Jan;51(1):1-9.

- ↑ Van Roy P, Briggs DE, Gaines RR. The Fezouata fossils of Morocco; an extraordinary record of marine life in the Early Ordovician. Journal of the Geological Society. 2015 Sep;172(5):541-9.

- ↑ Lamsdell JC. Evolutionary history of the dynamic horseshoe crab. International Wader Studies. 2019;21.

- ↑ Bicknell RD, Kimmig J, Budd GE, Legg DA, Bader KS, Haug C, Kaiser D, Laibl L, Tashman JN, Campione NE. Habitat and developmental constraints drove 330 million years of horseshoe crab evolution. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 2022 May 1;136(1):155-72.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Murphy A, Barich D, Fennessy MS, Slonczewski JL. An Ohio State Scenic River Shows Elevated Antibiotic Resistance Genes, Including Acinetobacter Tetracycline and Macrolide Resistance, Downstream of Wastewater Treatment Plant Effluent. Microbiology Spectrum. 2021 Sep 1;9(2):e00941-21.

Edited by Ifti Rahman, student of Joan Slonczewski for BIOL 116, 2024, Kenyon College.