Trichophyton rubrum: Difference between revisions

| Line 16: | Line 16: | ||

==Genome structure== | ==Genome structure== | ||

In the absence of complete m-RNA-based evidence, the complexity of filamentous fungi gene structures make gene interpretations challenging. Due to the lack of biochemical identification techniques available, pleomorphism, and cultural variability of Dermatophytes, the current knowledge of the T. rubrum genomic sequencing is limited and is in progress. | |||

Thus far, the cloning of cDNAs have enabled the generation of expressed sequence tags (ESTs) and have be found to effectively attribute to the identification processes undertaken. The T. rubrum genome has now been organized into five chromosomes. Altogether, estimated to be 22Mb in which 5 to 10% of the genome are repetitive DNA subunits of 8 and 50% AT content. To date, 43 unique nuclear-encoded genes have been analyzed, approximately more than half are proteases. | |||

==Cell and colony structure== | ==Cell and colony structure== | ||

Revision as of 19:17, 25 April 2012

A Microbial Biorealm page on the genus Trichophyton rubrum

Classification

Higher order taxa

Domain: Eukaryota; Kingdom: Fungi; Phylum: Ascomycota; Class: Eurotiomycetes; Order: Onygenales; Family: Arthrodermactaceae

Species

Genus: Trichophyton; Species: T. rubrum

Description and significance

Trichophyton rubrum, is the most common causitive of dermatophytosis worldwide, mainly occupying the humans’ feet, skin, and between fingernails. T. rubrum is known to be one of the most prominent anthrophilic species of dermatophtyes, appearing in various shades of white, yellow, brown, and red. It may also be found in various textures, being waxy, cottony, or smooth. Even though it is commonly observed, T. rubrum infections are incredibly hard to diagnose, and difficult to differentiate from other dermatophytes. Because this fungal pathogen is poorly understood, the discovery of its structure may significantly reduce the health costs of those who suffer various forms of dermatophytosis caused by T. rubrum.

Genome structure

In the absence of complete m-RNA-based evidence, the complexity of filamentous fungi gene structures make gene interpretations challenging. Due to the lack of biochemical identification techniques available, pleomorphism, and cultural variability of Dermatophytes, the current knowledge of the T. rubrum genomic sequencing is limited and is in progress. Thus far, the cloning of cDNAs have enabled the generation of expressed sequence tags (ESTs) and have be found to effectively attribute to the identification processes undertaken. The T. rubrum genome has now been organized into five chromosomes. Altogether, estimated to be 22Mb in which 5 to 10% of the genome are repetitive DNA subunits of 8 and 50% AT content. To date, 43 unique nuclear-encoded genes have been analyzed, approximately more than half are proteases.

Cell and colony structure

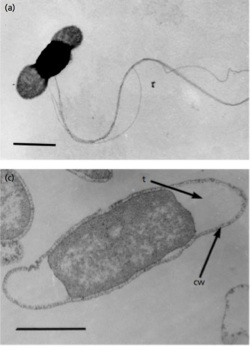

T. petrophila cells are rod-shaped and cell dimensions measure 2–7 μm long by 0.7–1 μm wide. This thermophilic species is motile, utilizing several lateral flagella for movement. The cell wall is typical of other gram negative bacteria with a thin layer of peptidoglycan with minimal cross-linking. Unlike other gram negative bacteria, species in the Thermotoga genus possess a peptidoglycan layer that does contain D-lysine and L-lysine.7

Unique to thermophiles in the Thermotoga genus, T. petrophila bacterium have a sheath-like outer membrane structure called a toga.1 The toga can form balloon-like protrusions on the ends of the rod shaped cells and this action creates a periplasmic space. The volume of this space can actually exceed the volume of the cytoplasm.7 The toga can be seen in the figure provided above.1

Metabolism

T. petrophila are heterotrophic obligate anaerobes and can grow in the presence of a variety of substrates. Growth has been detected when exposing the bacterium to medium including glucose, galactose, fructose, ribose, sucrose, arabinose, lactose, starch, maltose, peptone, yeast extract and also cellulose. This species can use these organic molecules as the sole source of energy as well as carbon through fermentation metabolism. One study reported lactate, acetate, H2 and CO2 as byproducts resulting from glucose fermentation.1 The cells can reduce elemental sulfur or thiosulfate to H2S, however, it was found that their cellular yields actually decreased when exposed to these electron acceptors.1

Mentioned above was the biofuel industry’s interest in hyperthermophilic enzymes involved in the catalytic breakdown of organic substrates. The major step in biofuel production is the degradation of an organic substrate such as cellulose into simpler sugars. It can take considerable energy to fuel reactions in order to break down cellulose and it is often done at high temperatures with varying pH levels. Using enzymes from thermophilic bacteria and archae which can tolerate these extreme conditions make them especially valuable. These thermostable enzymes can improve the efficiency of large scale reactions for biofuel production.9 Studies have indicated that specific purified enzymes from T. petrophila, along with enzymes from other bacterium in the Thermotoga genus, have effectively been able to function in the presence of harsh conditions, although the mechanism by which they are able to do so is still not well understood.9

More specific information regarding metabolic pathways can be found at the Joint Genome Institute’s website: http://img.jgi.doe.gov/cgi-bin/w/main.cgi?section=TaxonDetail&page=taxonDetail&taxon_oid=640427150 3

Ecology

Given their need for high temperatures and anaerobic environments, T. petrophila have been found to inhabit production waters on oil reservoirs. These oil stratifications reach high temperatures and are largely devoid of oxygen, making them ideal for this species of bacterium.1 Although T. petrophila has not been found to grow in geothermal areas such as volcanic hot springs, other species of the Thermotoga genus have been discovered in these regions, leading to the possibility that such regions could sustain life.10

Pathology

T. petrophila is non-pathogenic as the species has only been found free living in oil reservoirs.1,3 One study showed they exhibit some sensitivity when exposed to the antibiotics rifampicin, streptomycin, vancomycin or chloramphenicol. In fact, growth of T. petrophila was completely suppressed when exposed to these compounds.1

References

1. White, T., Henn, M., et al., Genomic Determinants of Infection in Dermatophyte Fungi. The Fungal Genome Initiative, Mar. 2012

2. De Biervre, C. and Dujon, B., Organisation of the mitochondrial genome of Trichophyton rubrum. Current Genetics, Volume 26, Issue 6: 553-559.

Edited by Melinda Dao of Dr. Lisa R. Moore, University of Southern Maine, Department of Biological Sciences, http://www.usm.maine.edu/bio