Dunaliella salina: Difference between revisions

S-konomura (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

S-konomura (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 26: | Line 26: | ||

=Ecology= | =Ecology= | ||

"Dunaliella salina" are found in high salt environments such as salted brines, salt evaporation ponds, and hypersaline lakes such as Great Salt Lake in Utah, USA [7]. The ability to tolerate high salt concentrations is fairly advantageous, since competition is minimal as salt high salt concentration inhibits growth for many other bacteria. "Dunaliella salina" was thought to be responsible for the red colouring of salted brines[1]. However, carotenoids responsible for the red colouration in D. salina are found in algal chloroplasts, whereas halophilic archaea also occupying hypersaline lakes have red pigments dispersed throughout the cell membrane [2]. Thus, "D. salina" has a much less overall impact to colouration and archaeal communities contribute more to the red colouration of hypersaline lakes. | "Dunaliella salina" are found in high salt environments such as salted brines, salt evaporation ponds, and [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hypersaline_lake hypersaline lakes] such as Great Salt Lake in Utah, USA [7]. The ability to tolerate high salt concentrations is fairly advantageous, since competition is minimal as salt high salt concentration inhibits growth for many other bacteria. "Dunaliella salina" was thought to be responsible for the red colouring of salted brines[1]. However, carotenoids responsible for the red colouration in D. salina are found in algal chloroplasts, whereas halophilic archaea also occupying hypersaline lakes have red pigments dispersed throughout the cell membrane [2]. Thus, "D. salina" has a much less overall impact to colouration and archaeal communities contribute more to the red colouration of hypersaline lakes. | ||

=Life Cycle= | =Life Cycle= | ||

"Dunaliella salina" can reproduce asexually, sexually and through division of motile vegetative cells[1]. Sexual reproduction, the formation of two gametes into a zygospore, is affected by salt concentrations[1]. Martinez et al. [10] determined the sexual activity of "D. salina" from evaluating ratio of zygotes and zygospores to total cells observed in culture. Low salt concentrations of 2% and 5% induced sexual activity, whereas higher salt concentration of 30% decreases sexual reproduction[10]. | "Dunaliella salina" can reproduce asexually, sexually and through division of motile vegetative cells[1]. Sexual reproduction, the formation of two gametes into a [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zygospore zygospore], is affected by salt concentrations[1]. Martinez et al. [10] determined the sexual activity of "D. salina" from evaluating ratio of zygotes and zygospores to total cells observed in culture. Low salt concentrations of 2% and 5% induced sexual activity, whereas higher salt concentration of 30% decreases sexual reproduction[10]. | ||

=Genome Structure= | =Genome Structure= | ||

| Line 38: | Line 38: | ||

=β-carotene= | =β-carotene= | ||

β-carotene is a type of pro-vitamin A, responsible for inhibiting the production of free radicals from ultraviolet light [3]. They are contained in the chloroplasts in lipid globules[9]. Among various carotenoid-rich microalgae, "D. salina" has the greatest carotene concentration making up ~10% algal dry weight[6]. Due to its ability to produce red pigmentation, β-carotene, the natural food colouring is highly demanded for cosmetic products[1]. β-carotene also contributes to the anti-oxidant effects of "D. salina"[11] and is used as an additive in human and animal nutrition for sources of vitamin A [3]. However, despite the positive contributions of "D. salina", commercial production is limited due to the low productivity of β-carotene [3]. Farhat et al. [3] studied the effects of salinity to maximize β-carotene production and found carotenoid concentration increases with increasing salinity. In order to maximize β-carotene production, "D. salina" should be grown in 1.5M to 3.0 M NaCl concentration until a stable cell density is reached then increased to 4.4 – 5.0 M NaCl concentration for maximum carotenoid production [3]. | β-carotene is a type of pro-vitamin A, responsible for inhibiting the production of [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Radical_(chemistry) free radicals] from ultraviolet light [3]. They are contained in the chloroplasts in lipid globules[9]. Among various carotenoid-rich microalgae, "D. salina" has the greatest carotene concentration making up ~10% algal dry weight[6]. Due to its ability to produce red pigmentation, β-carotene, the natural food colouring is highly demanded for cosmetic products[1]. β-carotene also contributes to the [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antioxidant anti-oxidant] effects of "D. salina"[11] and is used as an additive in human and animal nutrition for sources of vitamin A [3]. However, despite the positive contributions of "D. salina", commercial production is limited due to the low productivity of β-carotene [3]. Farhat et al. [3] studied the effects of salinity to maximize β-carotene production and found carotenoid concentration increases with increasing salinity. In order to maximize β-carotene production, "D. salina" should be grown in 1.5M to 3.0 M NaCl concentration until a stable cell density is reached then increased to 4.4 – 5.0 M NaCl concentration for maximum carotenoid production [3]. | ||

=Glycerol and Osmotic behaviour= | =Glycerol and Osmotic behaviour= | ||

"Dunaliella salina" lacks a rigid wall, and the plasma membrane alone makes the cell susceptible to osmotic pressure [1]. Glycerol is a compatible solute in which not only contributes to osmotic balance of the cell but also maintains enzyme activity (Brown as stated in Oren[1]). Glycerol is produced through two metabolic processes: intracellular synthesis through a photosynthetic product and metabolism of starch in the cell [15]. The cell membrane of "D. salina" has low permeability to glycerol to prevent glycerol from leaving the cell [13], accounting for the high concentration inside the cell. Glycerol synthesis from starch is regulated through osmotic changes as shown in Figure 5. High extracellular salt concentration drives the synthesis of glucose. Osmotic stress affects enzyme activity of key enzymes of the glycerol metabolic pathway: glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, glycerol-3-phosphate phosphatase, dihydroxyacetone reductase, and dihydroxyacetone kinase[15]. These enzymes regulate glycerol requirements of the cell by responding to osmotic stresses. Johnson et al. [14] found that high salt concentration inside cells decrease enzymatic activity. Thus, while "D. salina" live in high salt concentrations, they maintain a relatively low concentration of sodium inside [15]. | "Dunaliella salina" lacks a rigid wall, and the plasma membrane alone makes the cell susceptible to [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Osmotic_pressure osmotic pressure] [1]. Glycerol is a compatible solute in which not only contributes to osmotic balance of the cell but also maintains enzyme activity (Brown as stated in Oren[1]). Glycerol is produced through two metabolic processes: intracellular synthesis through a photosynthetic product and metabolism of starch in the cell [15]. The cell membrane of "D. salina" has low permeability to glycerol to prevent glycerol from leaving the cell [13], accounting for the high concentration inside the cell. Glycerol synthesis from starch is regulated through osmotic changes as shown in Figure 5. High extracellular salt concentration drives the synthesis of glucose. Osmotic stress affects enzyme activity of key enzymes of the glycerol metabolic pathway: glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, glycerol-3-phosphate phosphatase, dihydroxyacetone reductase, and dihydroxyacetone kinase[15]. These enzymes regulate glycerol requirements of the cell by responding to osmotic stresses. Johnson et al. [14] found that high salt concentration inside cells decrease enzymatic activity. Thus, while "D. salina" live in high salt concentrations, they maintain a relatively low concentration of sodium inside [15]. | ||

Revision as of 01:36, 2 December 2012

Classification

Higher order Taxa

Bacteria (Domain); Chlorophyta (Phylum); Chlorophyceae (Class); Volvocales (Order); Dunaliellaceae (Family); Dunaliella (Genus).

Species

Dunaliella salina

Description and Significance

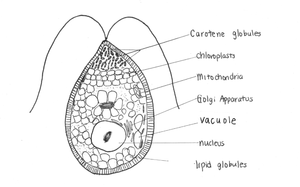

The halophile, "Dunaliella salina" is a unicellular, green alga found in environments with high salt concentration [1]. It produces a distinct pink and red colour in saltern ponds [2]. Michel Felix Dunal first discovered "D. salina" in 1838 in the south of France occupying salt evaporation ponds; however, it was not named until 1905 by Teodoresco [1]. "Dunaliella" species are able to tolerate varying NaCl concentrations, ranging from 0.2% to approximately 35% [3]. Thus, "Dunaliella salina" is found in high densities in saline lakes. In order to survive such high salinity environments, "D. salina" accumulates β-carotene in protection against intense light, and glycerol to balances osmotic pressure. "Dunaliella salina" offers a potential in biotechnological applications for the purpose of commercial products due to β-carotene production [4]. "Dunaliella salina" is a model organism to study the effects of saline adaptation in algae [1]. In addition, the role of glycerol in "D. salina" as a key organic compatible solute to give osmotic balance has allowed for the establishment of knowledge of the general concept [1].

Ecology

"Dunaliella salina" are found in high salt environments such as salted brines, salt evaporation ponds, and hypersaline lakes such as Great Salt Lake in Utah, USA [7]. The ability to tolerate high salt concentrations is fairly advantageous, since competition is minimal as salt high salt concentration inhibits growth for many other bacteria. "Dunaliella salina" was thought to be responsible for the red colouring of salted brines[1]. However, carotenoids responsible for the red colouration in D. salina are found in algal chloroplasts, whereas halophilic archaea also occupying hypersaline lakes have red pigments dispersed throughout the cell membrane [2]. Thus, "D. salina" has a much less overall impact to colouration and archaeal communities contribute more to the red colouration of hypersaline lakes.

Life Cycle

"Dunaliella salina" can reproduce asexually, sexually and through division of motile vegetative cells[1]. Sexual reproduction, the formation of two gametes into a zygospore, is affected by salt concentrations[1]. Martinez et al. [10] determined the sexual activity of "D. salina" from evaluating ratio of zygotes and zygospores to total cells observed in culture. Low salt concentrations of 2% and 5% induced sexual activity, whereas higher salt concentration of 30% decreases sexual reproduction[10].

Genome Structure

The sequencing of "Dunaliella species" is important to isolate different species for commercial purposes. Olmos et al.[8] sequenced five species of "Dunaliella" using their 18S ribosomal RNA genes. "Dunaliella salina" contains only one intron, as opposed to two and three for "D. parva" and "D. bardavil" respectively. The mitochondrial and plastic genome sequence are circular and large with approximately 60% non-coding DNA [9]. The mitochondrial and plastid genome contains 28.3 (12 genes) and 269 kb (102 genes) respectively [9]. In addition, Smith et al. [9] found that both genomes are highly occupied with introns: mitochondrial DNA (58%) and plasmid DNA (65.5%). The GC content of "D. salina" is relatively low compared to other Chlamydomonadales at 34.4% for mitochondrial

β-carotene

β-carotene is a type of pro-vitamin A, responsible for inhibiting the production of free radicals from ultraviolet light [3]. They are contained in the chloroplasts in lipid globules[9]. Among various carotenoid-rich microalgae, "D. salina" has the greatest carotene concentration making up ~10% algal dry weight[6]. Due to its ability to produce red pigmentation, β-carotene, the natural food colouring is highly demanded for cosmetic products[1]. β-carotene also contributes to the anti-oxidant effects of "D. salina"[11] and is used as an additive in human and animal nutrition for sources of vitamin A [3]. However, despite the positive contributions of "D. salina", commercial production is limited due to the low productivity of β-carotene [3]. Farhat et al. [3] studied the effects of salinity to maximize β-carotene production and found carotenoid concentration increases with increasing salinity. In order to maximize β-carotene production, "D. salina" should be grown in 1.5M to 3.0 M NaCl concentration until a stable cell density is reached then increased to 4.4 – 5.0 M NaCl concentration for maximum carotenoid production [3].

Glycerol and Osmotic behaviour

"Dunaliella salina" lacks a rigid wall, and the plasma membrane alone makes the cell susceptible to osmotic pressure [1]. Glycerol is a compatible solute in which not only contributes to osmotic balance of the cell but also maintains enzyme activity (Brown as stated in Oren[1]). Glycerol is produced through two metabolic processes: intracellular synthesis through a photosynthetic product and metabolism of starch in the cell [15]. The cell membrane of "D. salina" has low permeability to glycerol to prevent glycerol from leaving the cell [13], accounting for the high concentration inside the cell. Glycerol synthesis from starch is regulated through osmotic changes as shown in Figure 5. High extracellular salt concentration drives the synthesis of glucose. Osmotic stress affects enzyme activity of key enzymes of the glycerol metabolic pathway: glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, glycerol-3-phosphate phosphatase, dihydroxyacetone reductase, and dihydroxyacetone kinase[15]. These enzymes regulate glycerol requirements of the cell by responding to osmotic stresses. Johnson et al. [14] found that high salt concentration inside cells decrease enzymatic activity. Thus, while "D. salina" live in high salt concentrations, they maintain a relatively low concentration of sodium inside [15].

References

1. Oren A. “A century years of Dunaliella research: 1905-2005.” Saline Systems, 2005. 2. Oren A. and Rodriguez-Valera F. “The contribution of halophilic Bacteria to the red coloration of saltern crystallizer ponds.” FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 2001. 3. Farahat N., Rabhi M., Falleh H., Jouini J., Abdelly C. and Smaoui A. “Optimization of salt concentrations for a higher carotenoid production in Dunaliella salina (Chlorophyceae).” Phycological Society of America, 2011. DOI: 10.1111/j.1529-8817.2011.01036.x 4. Schilipaulis L. “The Extensive Commercial Cultivation of Dunaliella.” Bioresource Technology, 1991. DOI: 10.1016/0960-8524(91)90162-D 5. What is Dunaliella salina? n.d. Web. 22 Nov. 2012. <http://blog.recoverye21.com/dunaliella-salina/> 6. Shariati M., Hadi M.R. “Microalgal Biotechnology and Bioenergy in Dunaliella” Biomedical Engineering, 2011. DOI: 10.5772/19046 7. Brock T. “Salinity and the Ecology of Dunaliella from Great Salt Lake.” Journal of General Microbiology, 1975. 8. Olmos J., Paniagua J. and Contreras R. “Molecular identification of Dunaliella sp. utilizing the 18S rDNA gene.” Letters in Applied Microbiology, 2000. 9. Smith D., Lee R., Cushman J., Magnuson J., Tran D. and Polle J.” The Dunaliella salina organelle genomes: large sequences, inflated with intronic and intergenic DNA.” BMA Plant Biology, 2010. DOI: 10.1186/1471-2229-10-83 10. Martinez G., Cifuentes A., Gonzalez M. and Parra O. “Effect of salinity on sexual activity of Dunaliella salina (Dunal) Teodoresco, strain CONC-006.” Revista Chilena de Historia Natural, 1995. 11. Tammam A., Fakhry E. and El-Sheekh M. “Effect of salt stress on antioxidant system and the metabolism of the reactive oxygen species in Dunaliella saline and Dunaliella tertiolecta.” African Journal of Biotechnology, 2011. DOI: 10.5897/AJB10.2392 12. Wengmann K. “Osmotic Regulation of photosynthetic Glycerol Production in Dunaliella.” Biochimica et biophysica acta, 1971. 13. Gimmler H. and Hartung W. “Low Permeability of the Plasma Membrane of Dunaliella parva for Solutes.” Journal of Plant Physiology, 1988. DOI: 10.1016/S0176-1617(88)80132-9 14. Johnson M., Johnson E., MacElroy R., Speer H. and Bruff B. “Effects of Salts on Halophilic Alga Dunaliella viridis.” Journal of Bacteriology, 1968. 15. Chen H., Lu Y. and Jiang J. “Comparative Analysis on the Key Enzymes of the Glycerol Cycle Metabolic Pathway in Dunaliella salina under Osmotic Stresses.” PLoS ONE, 2012, DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037578 16. Heakal F., Hefny M., El-Tawab A., “Electrochemical behaviour of 340L stainless steel in high saline and sulphate solutions containing alga Dunaliella salina and β-carotene. Journal of Alloys and Compounds, 2010, DOI: 10.1016/j.jallcom.2009.11.028 17. Mixed Carotenoids. Rejuvenal healthy aging, n.d. We

Edited by Saki Konomura, student of MICB 301 at the University of British Columbia