Gas gangrene (Clostridial myonecrosis)

Pathology

By Yiyi Ma

Clostridial myonecrosis (gas gangrene) is a necrotizing soft tissue infection that targets skeletal muscle. It is typically caused by Clostridium perfrigens, Clostridium septicum, and Clostridium novyi.[1] It is opportunistic infection that is extremely fast spreading and highly lethal. Clostridium is a genus of anaerobic bacteria, gram positive bacteria. Clostridium use anaerobic fermentation to produce hydrogen gas and carbon dioxide, creating the gas in the blisters that are symptomatic of gas gangrene. 80-90% of gas gangrene cases are caused by Clostridium perfrigens. Clostrdium are ubiquitous and species can be found in environments ranging from the human gastrointestinal tract to soil.[2] Clostridial myonecrosis typically occurs when open or traumatic wounds are exposed to these bacteria and subsequently become contaminated with spores or vegetative cells. Historically, gas gangrene has been associated with battlefield wounds but is now mostly obsolete due to modern advances in health and technology.[3] Modern cases of clostridial myonecrosis also include surgical contamination and also spontaneous infection. Most infections happen under circumstances of poor vascular health or vascular damage which obstruct blood flow and allow anoxic tissue.[3] Presently, about 90% of contaminated traumatic wounds exhibit Clostridium culture but less than 2% develop myonecrosis.[1] Myonecrosis can also occur without an open wound if blood flow to tissues is reduced. Because of this, people who have vascular disease affecting blood flow to extremities (such as diabetes mellitus or atherosclerosis) have a higher risk of mortality.[1] Untreated clostridial myonecrosis carries a 100% fatality rate. Treated myonecrosis has a mortality rate of 20-30% and spontaneous cases have a mortality rate between 67-100%. Infections in the trunk of the body have a higher mortality rate than extremities such as arms or legs.[1] Myonecrosis most commonly occurs in the extremities and symptoms of infection develop six to forty-eight hours after initial infection of Clostridium. Initial symptoms of infection include sudden and severe pain in the site of infection before clinical signs are noticeable. Body temperature is initially within normal range but quickly rises soon after. Skin surrounding the infection site is initially tight and shiny but then quickly becomes greyish and then dark. Muscles are dark red, black, or green and do not contract or bleed. A sickly sweet odor is often present. Necrosis can spread as quickly as 6 inches per hour.[4] Shock and death can occur within 12 hours. Because infection is very aggressive and progresses extremely quickly, treatment must also be aggressive, ranging from antibiotics to amputation.[5] Infections are typically characterized with very little host response to Clostridium. Immune response is in reaction to exotoxins produced by Clostridium rather than actual bacterium. There is usually no pus created during infection.[1]The exact reason as to why there is poor immune response is not exactly known. For infection to happen, the partial pressure of oxygen must be low enough for Clostridium to grow. Clostridium perfrigens are not strict anaerobic bacteria, they can grow freely in 30% oxygen and 70% oxygen severely reduces their growth. After infection, incubation of Clostridium can range from one hour to many weeks. Toxins such as lecithinase, collagenase, hyaluronidase, hemagglutinin and hemolysin toxins are released into the surrounding tissue. Types of toxins include theta, kappa and alpha-toxin. Theta- toxin causes vascular injury and destroys leukocytes. Kappa toxin destroys connective tissue and helps speed the necrosis. Alpha-toxin lyses red blood cells, leukocytes, platelets, myocytes, and fibroblasts. Symptoms of gas gangrene include:[5] - Fever, vomiting, increased heart rate and sweating - Painful swelling around wound - Pale skin that turns grey, purple, black or dark red - Blisters with smelly discharge - Jaundice

Types

Clostridium perfrigens produces more than twelve toxins that may be disease-causing. At least eight of the toxins are thought to be lethal. The major toxins of Clostridium perfrigens are alpha, beta, epsilon, and iota. These toxins group C. perfrigens into the five toxigenic types: A, B, C, D, and E. Type A strains produce mostly alpha-toxin. Type B strains produce beta and epsilon toxins. Type C strains produce beta and delta toxins. Type D produce the epsilon toxin and type E produces iota toxin.[6] Like alpha-toxin, beta-toxin releases arachidonic acid and produce transmembrane pores in eukaryotic cells and have hemolytic activity.[7] Delta-toxin is also a hemolytic toxin that bind to the GM2 ganglioside on erythrocytes.[8] Kappa-toxin digests collagen in connective tissues, breaking down skeletal muscle. Epsilon-toxin is a toxin that forms pore. The pores leak red blood cells and serum proteins.[9]Iota-toxin is a binary toxin that performs ADP-ribosylation of actin.[10]

Theta-Toxin

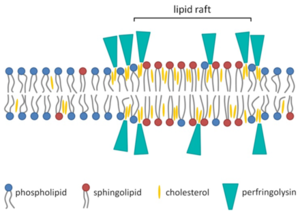

Theta (θ) toxin, also known as perfringolysin O (PFO) is a toxin secreted by Clostridium perfringens that is a pore-forming chlosterol-dependent cytolysin. PFO is expressed in almost all Clostridium perfrigens strains and plays a role in gas gangrene advancement. The genes for producing PFO and alpha-toxin are located on the chromosome rather than on the plasmid (such as beta, epsilon and iota). Although PFO is widely encoded by most C. perfrigens strains, some food-poisoning strains do not have the PFO gene.[11] PFO is an average sized protein (500 amino acids) that varies in protein structure and gene location. This effects virulence of the bacteria and is likely explained by recombination.[11] PFO also contains a signal peptide that helps secretion through general secretory pathway (GSP). When traversing the cell membrane, it is cleaved. In solution at high concentrations, PFO likely forms high concentrations with a head-to-tail structure. PFO monomers contain four domains that are mostly β-barrels. PFO is dependent on cholesterol as a cellular receptor for pore formation. Cholesterol is ubiquitous in mammalian membranes. The mechanism of PFO cytolysis of mammalian cells begins with the loops of domain four attaching to the plasma membrane of the eukaryotic cell. One of the loops contains a conserved undecapeptide which helps anchor the PFO to the membrane of the cell and initiate necessary conformational changes to allow the β-barrel to enter the membrane of the eukaryotic cells. Binding capacity of the PFO may be dependent on the accessibility of the cholesterol in the cellular membrane, which is dependent on the spacing of the phospholipid groups and the saturation level of the cholesterol-phospholipid acyl chain.[11] Thickness of the phospholipid bilayer may affect the efficiency of pore formation by PFO. When domain four binds to the eukaryotic cellular membrane, the PFO molecule undergoes structural changes and allows association with another monomer. The prepore structure then forms. The prepore structure is made of oligomerized monomers that have not inserted the β-barrel into the membrane yet. Two amphipathic transmembrane β-hairpins are inserted into the membrane by each monomer. Every single monomer does same action in synchronization.

Alpha and Theta-Toxin Synergy in Immune Response

The PFO gene acts synergistically with the alpha-toxin gene, with drastically decreased virulence in mutant strains lacking both genes. Clostridial myonecrosis is often characterized by poor immune response. The immune system is capable to killing unidentified C. perfrigens in both anaerobic and aerobic conditions—the problem is not in the killing ability of the immune system but rather the evasiveness and indirect methods of blocking the immune system that the bacteria uses. Alpha-toxin also directly promotes platelet aggregation and PFO promotes an increased expression of adhesion molecules. The combination of the two toxins promotes increased leukocyte adhesion through upregulation of adhesion molecules to endothelial cells after subjection to the alpha-toxin.[3] Normally, these markers would help traffic neutrophils into the site of infection. However, the upregulation of increased adherence traps the neutrophils into the lining of the blood vessels, causing thrombosis, edema and poor blood flow.[11] This, in turn, results in poor movement of leukocytes to the area of infection and contributes to low levels of oxygen and increased growth and spread of Clostridium. C. Perfrigens is able to evade the phagosome only through the presence of both PFO and alpha-toxin. PFO is also critical for macrophage cytotoxicity.[12]PFO’s effect on the eukaryotic membrane benefits the bacteria because it also aids in escape of the macrophage. Although immune response is poor, it is not absent. Infection still requires a moderately large population of bacteria, showing that the immune system does play a role in obstructing the infection.[12]

Alpha-Toxin

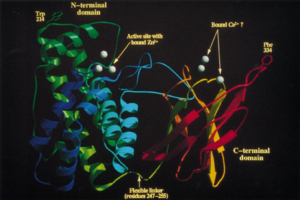

Alpha-toxin, or phospholipase C (PLC), degrades lecithin and sphingomyelin in eukaryotic cell membranes. Lecithin is any sort of yellow-brown fatty acid substances which are amphiphilic and sphingomyelin, a type of sphingolipid found in eukaryotic membranes.7 Alpha-toxin is uniquely an enzyme and also has contains two Zn2+ ions that are essential for catalysis.9 The structure of alpha-toxin contains two domains with the N-terminal composed of α-helices and the C-terminal composed of β-sheets. The N-domain contains the phospholipase C active site.9 The function of the C-domain is not fully understood, however recent studies suggest that the C-domain may be important for the interaction between alpha-toxin and membrane phospholipids through calcium ions that are coordinated by the amino acid residues.9 There are structural variants of the alpha-toxin, individual to the bacterium. Structural differences usually do not affect the phospholipase C activity but may have biological significance. Some variations are more resistant to degradation.9

By Yiyi Ma

Introduction starts here

At right is a sample image insertion. It works for any image uploaded anywhere to MicrobeWiki.

The insertion code consists of:

Double brackets: [[

Filename: PHIL_1181_lores.jpg

Thumbnail status: |thumb|

Pixel size: |300px|

Placement on page: |right|

Legend/credit: Electron micrograph of the Ebola Zaire virus. This was the first photo ever taken of the virus, on 10/13/1976. By Dr. F.A. Murphy, now at U.C. Davis, then at the CDC.

Closed double brackets: ]]

Other examples:

Bold

Italic

Subscript: H2O

Superscript: Fe3+

Introduce the topic of your paper. What is your research question? What experiments have addressed your question? Applications for medicine and/or environment?

Sample citations: [13]

[14]

A citation code consists of a hyperlinked reference within "ref" begin and end codes.

Section 1

Include some current research, with at least one figure showing data.

Every point of information REQUIRES CITATION using the citation tool shown above.

Section 2

Include some current research, with at least one figure showing data.

Section 3

Include some current research, with at least one figure showing data.

Section 4

Conclusion

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1. Qureshi, S., MD. (2017, January 18). Clostridial Gas Gangrene (J. Geibel MD, Ed.). Retrieved April 23, 2017, from http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/214992-overview#a4

- ↑ 1. Clostridium perfringens, their Properties and their Detection. (n.d.). Retrieved April 24, 2017, from http://www.sigmaaldrich.com/technical-documents/articles/analytix/clostridium-perfringens.html

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 1. Titball, Richard W., Claire E. Naylor, and Ajit K. Basak. "The Clostridium perfringensα-toxin." Anaerobe 5.2 (1999): 51-64.

- ↑ 1. Bakker, D. J. (2012). Clostridial myonecrosis (gas gangrene). Undersea & Hyperbaric Medicine, 39(3), 731.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 1. Pietrangelo, A., MD, & Cirino, E., MD. (2016, February 16). Gas Gangrene. Retrieved April 23, 2017, from http://www.healthline.com/health/gas-gangrene#overview1

- ↑ 1. McDonel, J. L. (1980). Clostridium perfringens toxins (type a, b, c, d, e). Pharmacology & therapeutics, 10(3), 617-655.

- ↑ 1. Steinthorsdottir, V., Halldórsson, H., & Andrésson, O. S. (2000). Clostridium perfringens beta-toxin forms multimeric transmembrane pores in human endothelial cells. Microbial pathogenesis, 28(1), 45-50.

- ↑ 1. Cavaillon, J. M., Jolivet-Reynaud, C., Fitting, C., David, B., & Alouf, J. E. (1986). Ganglioside identification on human monocyte membrane with Clostridium perfringens delta-toxin. Journal of leukocyte biology, 40(1), 65-72.

- ↑ Cole, A. R., Gibert, M., Popoff, M., Moss, D. S., Titball, R. W., & Basak, A. K. (2004). Clostridium perfringens [straight epsilon]-toxin shows structural similarity to the pore-forming toxin aerolysin. Nature structural & molecular biology, 11(8), 797

- ↑ 1. Tsuge, H., Nagahama, M., Nishimura, H., Hisatsune, J., Sakaguchi, Y., Itogawa, Y., ... & Sakurai, J. (2003). Crystal structure and site-directed mutagenesis of enzymatic components from Clostridium perfringens iota-toxin. Journal of molecular biology, 325(3), 471-483.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 1. Verherstraeten S, Goossens E, Valgaeren B, et al. Perfringolysin O: The Underrated Clostridium perfringens Toxin? Popoff MR, ed. Toxins. 2015;7(5):1702-1721. doi:10.3390/toxins7051702.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 1. O'Brien, D. K., & Melville, S. B. (2004). Effects of Clostridium perfringens alpha-toxin (PLC) and perfringolysin O (PFO) on cytotoxicity to macrophages, on escape from the phagosomes of macrophages, and on persistence of C. perfringens in host tissues. Infection and immunity, 72(9), 5204-5215.

- ↑ Hodgkin, J. and Partridge, F.A. "Caenorhabditis elegans meets microsporidia: the nematode killers from Paris." 2008. PLoS Biology 6:2634-2637.

- ↑ Bartlett et al.: Oncolytic viruses as therapeutic cancer vaccines. Molecular Cancer 2013 12:103.

Authored for BIOL 238 Microbiology, taught by Joan Slonczewski, 2017, Kenyon College.