Infanticide in Primates

Introduction

Infanticide (in animals) generally refers to the killing of an infant or a young offspring by an adult or mature individual of the same species and is observed in a variety of species ranging from humans to microscopic rotifers and especially in primates. Both males and females can be the perpetrators of infanticide in animals and both parents (filial infanticide) and non-parent individuals have been observed to display the behavior. Filial infanticide, which can be accompanied by cannibalism (filial cannibalism), is widespread in fishes and is also seen in terrestrial animals. It has been estimated that infanticide occurs in 25% of all mammals and, in some of these populations, infanticide is a major contributor to infant mortality.[1]

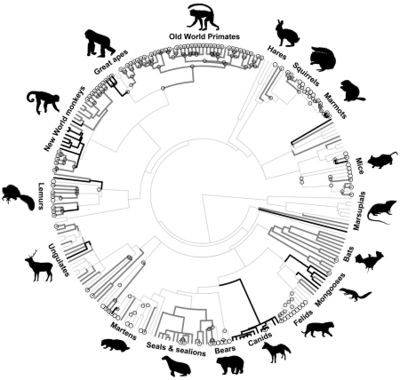

Many primates such as the gorilla, chimpanzee, baboon, and langur have been known to practice infanticide while others, such as the orangutan, bonobo and mouse lemur have not been observed to do so[1]. Although previously considered pathological and maladaptive and attributed to environmental conditions such as overcrowding and captivity [2], there are currently several explanations for why infanticide has evolved in non-human primate communities. Interestingly, the frequency and distribution of infanticide seems to suggest that there is a correlation between infanticide risk and social organization in mammals and primates. Male infanticide occurs most frequently in social species, less frequently in solitary species and least frequently in monogamous species.[3] The fitness advantage the behavior has, the associated costs and the different ways it is thought to have affected the structure of primate populations have made the evolution and genetics of the behavior very interesting to study.

https://www.upi.com/Science_News/2014/11/13/Big-testes-are-sign-that-a-species-has-history-of-infanticide/8601415916184/.

Section 1 Evolution and Genetics of Behavior

Several explanations have been proposed for the existence and evolution of infanticide in non- human primates. The benefits of infanticide for male non-human primates, and its costs to females, probably vary across mammalian social and mating systems [3] and between different primate species as well. Infanticidal behavior can be adaptive because of nutritive benefits individuals gain from cannibalism, conservation of resources by eliminating competitors and paternal manipulation in which parents terminate investment in particular offspring by killing (and often consuming) them [4]. The prevailing adaptive explanation for the behavior, however, has been the sexual-selection hypothesis according to which males increase reproductive opportunity by killing unrelated, unweaned offspring, thus hastening the mother's next ovulation, at which time the infanticidal male can mate with her [5]. Alternate nonadaptive explanations such as social-pathology and side effect hypotheses have also been proposed.[5]

Males in primate groups often exploit infants to which they are not related in ways that lead to the death of the infant. Several primate species have been observed to engage in the killing and subsequent cannibalism of infants. This type of behavior has also been seen in the great apes such as bonobos and chimpanzees (new scientist). In chimpanzees, cannibalism has been suggested to be the primary function of infanticide (6). Infants may also be used as protective buffers in primate groups during agnostic encounters (conflicts) between males which can result in the death of the infant (7). Females in primate groups also kill or cannibalize infants although usually for motivations different from nutrition (5).

Sample citations: [6]

[7]

A citation code consists of a hyperlinked reference within "ref" begin and end codes.

Section 2 Microbiome

Include some current research, with a second image.

Conclusion

Overall text length should be at least 1,000 words (before counting references), with at least 2 images. Include at least 5 references under Reference section.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 [Dunham, Will. “Infanticide Common among Adult Males in Many Mammal Species.” Reuters, Thomson Reuters, 13 Nov. 2014, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-science-infanticide/infanticide-common-among-adult-males-in-many-mammal-species-idUSKCN0IX2BA20141113.]

- ↑ Moore, Jim. “Population Density, Social Pathology, and Behavioral Ecology.” Primates, vol. 40, no. 1, 1999, pp. 1–22., doi:10.1007/bf02557698.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Lukas, D., and E. Huchard. “The Evolution of Infanticide by Males in Mammalian Societies.” Science, vol. 346, no. 6211, 2014, pp. 841–844., doi:10.1126/science.1257226.

- ↑ Palombit, Ryne A. “Infanticide as Sexual Conflict: Coevolution of Male Strategies and Female Counterstrategies.” Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology, vol. 7, no. 6, 2015, doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a017640

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Hrdy, Sarah Blaffer. “Infanticide among Animals: A Review, Classification, and Examination of the Implications for the Reproductive Strategies of Females.” Ethology and Sociobiology, vol. 1, no. 1, 1979, pp. 13–40., doi:10.1016/0162-3095(79)90004-9

- ↑ Hodgkin, J. and Partridge, F.A. "Caenorhabditis elegans meets microsporidia: the nematode killers from Paris." 2008. PLoS Biology 6:2634-2637.

- ↑ Bartlett et al.: Oncolytic viruses as therapeutic cancer vaccines. Molecular Cancer 2013 12:103.

Edited by MEHERET OURGESSA, student of Joan Slonczewski for BIOL 116 Information in Living Systems, 2019, Kenyon College.