Evolution of Dolphins

Introduction

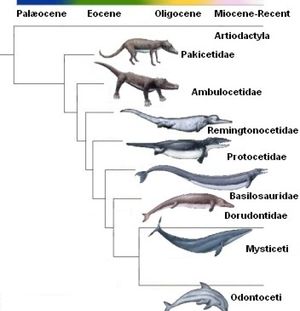

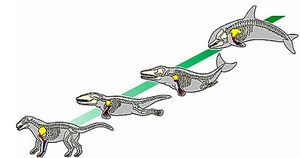

The evolution of dolphins, or Delphinus, is believed to have started with the Pakiectus a four legged, land walking mammal. The Pakiectus dates back to approximately 50 million years ago. Throughout the centuries, these animals have gone through drastic changes to become the modern day dolphin. Along with the Pakiectus, the dolphin is thought to have evolved alongside or from the Ambulocetus, Remingtonocetidae, Protocetid, Basilosaurudae, and Dorudontid to eventually become the Delphinus which is found in the Cetacea infraorder.[1] Other studies suggest that the Squalodontidae, Aetiocetidae, and Kentriodontidae also contributed to the evolution of Delphinus.[2] The Pakiectus lived near the shallow waters and began to feed on organisms that lived in these waters, which began the transition from terrestrial to aquatic animals. The bone structure of the flipper in the modern dolphin is very similar to the structure found in the Pakiectus legs and hooves, confirming the link between the two organisms.[3]

Over the 50 million years of evolution, the ancestors of dolphins adapted from being terrestrial to aquatic. A characteristic that is mainly found in terrestrial animals is that of a vertical spine. Dolphins have vertical spines leaving them swimming with vertical movements, while fish movements are horizontal.Cite error: Closing </ref> missing for <ref> tag

Genetic Adaptations

The common dolphins underwent centuries of evolution to move from terrestrial to aquatic mammals. These mammals share much of their evolution with the other members of the Cetacea. Various genes influencing anatomical structure went through positive selection, or Darwinian selection, to help the dolphin take the form currently exhibited. Numerous studies show the about 2.26%-4.8% of the dolphin’s genes, equating to approximately 376 genes in total, were selected for. This gene selection is believed to help the overall system development, pattern of specification process, and mesoderm development.[4] Morphological evolution is evident as the Delphinus form is significantly different than the body of the Pakicetus. In dolphins, there is a overrepresentation in genes of MET, FOXP2, TRIM63, FOXO3, CD2, and PTCH1 which are possibly responsible for the morphological evolution. Evidence shows that there could be changes in transcription factors, expression patterns, and in protein function that is also responsible for the morphological changes.[5]

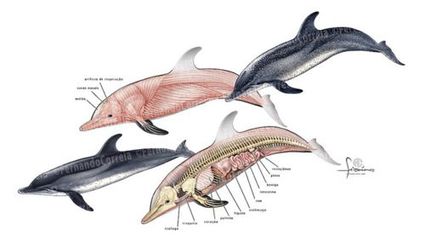

Adapting to the aquatics lifestyle required changes to the internal body and function of the the Delphinus. Being that dolphins live in the water, there is a much higher need of kidney function. The amount of water that flows through and around the dolphin is significantly more than the terrestrial mammals. The genes SMAD1, NPNT, LEF1, SERPINF1, and AQP2 are critical for the modifications of the kidney.[6] These genes allow for the dolphins to have a reniculate kidney. Reniculate kidneys are found in aquatic mammals. They allow for a large surface area for removing toxins from the body more efficiently. Aquatic mammals such as Delphinus, don’t have specialized glands for excreting salts from the body as terrestrial mammals do - sweating. With the reniculate kidney dolphins are able to gain water from seawater without any harm.[7][8]

The heart of a dolphin is approximately 33 times larger than that of a cow, a terrestrial mammal. Specific genes were adapted to allow for the diving motion required for the aquatic lifestyle. Genes ADAM9, NKX2, CAD15, CRFR2, GDF9, CADH3, TAB2, and PLN are the specific genes that generated the adjustments need for the new environment. All eight of these genes allowed for anastomoses, or cross-connection, between the dorsal and ventral inter ventricular arteries. The anastomoses allows for the Delphinus to either conserve or dissipate body heat.[9] Another adaptation that the genes contribute to is hypertrophy, an increased growth of muscle cells, of the right ventricle.[10][11]

Living below the surface of water requires an adaptation to the lungs due to the lack of oxygen in the environment. Delphinus, along with other Cetacea, breath through their lungs, not gills as many other aquatic mammals do. Among all the organisms in the world, the Cetacean has the most modified lung. Increased cartilage support, reinforcement of peripheral airways, loss of respiratory bronchioles, and presence of bronchial sphincters are all adaptions from the genes RSPO2, LEF1, and FOXP2. Many of these adaptions are in response to the new diving motion from living in the aquatics.[12] In order to breath in oxygen, dolphins use their “nostrils” that are located at the top of their body, also known as a blowhole. The bronchiole sphincters make it possible for the dolphin to seal off the water from entering the lungs and hold in oxygen for extensive amounts of time.[13]

The external features of the Delphinus have also adapted to living in the marine environment. Homeotic development involves genes that regulate the anatomic structure of organisms. The 5’HoxD genes, homeotic genes, are three times higher in Cetaceans than in terrestrial animals when comparing the ratio of non-synonymous to synonymous substitutions.[14] The significant increase in 5’HoxD genes is suggested to be correlated with the change in body structure.

Light travels differently when submerged in water, which leads to a necessary adaptation to the eyes. In dolphins, the POU4F2, NES, and FOXP2 genes help with sight under and above water.[15] The adapted corneas and lenses are shaped to be able to see light through water. With the changed genes, the dolphin’s ocular muscles are able to bend to see aerial vision as well as underwater vision.[16] Dolphins have good night vision due to the tapetum lucidum, which is attached to the retina. The tapetum lucidum reflects on the lens to allow for better night vision. Other morphological changes to the dolphin eye are to the optics, retina, and possible different other eye structures.[17]

Being that the Delphinus was once a terrestrial, land walking Pakicetus, Delphinuses have vestigial hind limbs found in the body all of Cetaceans.[18] The genes RSPO2 and PTCH1 contributed to the progressive reduction and loss of the hindlimb and development of tail flukes.[19][20] There was gradual dissociation of the pelvic girdle from the vertebral column as the hind limbs became less useful to the dolphins.

Unlike most terrestrial mammals, the aquatic Delphinus does not need hair. Gene TGM3 is responsible for the adapted hairless dolphin. This lack of hair increase the hydrodynamic and subaquatic movements.[21]

After approximately 50 million years, the Delphinus evolved from the terrestrial Pakicetus to the modern aquatic dolphin.[22] Throughout these millions of years, it is believed the there were no mutations that contributed to the development of the modern dolphin. Scientist believe the various adaptions were due to simply natural selection and genetic drift. In order to understand how positive selection plays a role in the natural selection, there would need to be an understanding of speciation and the nature of adaption.[23] Research is currently being preformed to find further answers to the unknowns of dolphin evolution and evolution as a whole.

Microbiome

For the Delphinus, along with many other marine animals, it is important to have good immune systems due to the new threats to the ecosystem with climate change, habitat degradation, and human impact. Numerous dolphin deaths have been associated with viruses, bacteria, fungi, and parasites. Marine life has the highest bacterial diversity, one study found 48 phyla with pyrosequencing. The most amount of these phyla, exactly 30 phyla, were found in the oral, gastric fluid, and chuff specimens. Most of these bacteria were Proteobacteria and Bacteroidetes, except for the rectal specimens which had low Bacteroides sequences. About 13 candidate phyla, no laboratory-cultivated isolates, were also found, mostly in the oral, gastric, and respiratory specimens. Due to the high concentration of bacterial taxa in the seawater, the novelty of bacteria within the dolphin is greater.

Conclusion

Overall text length should be at least 1,000 words (before counting references), with at least 2 images. Include at least 5 references under Reference section.

References

- ↑ Mark Caney, “Evolution of Dolphins” 2019. Dolphin Way

- ↑ Bapor Kibra, Willemstad, Curaçao, “Learn About Dolphin Evolution” 2019. Dolphin Academy

- ↑ https://www.dolphins-world.com/dolphin-evolution/ Dolphins-World, “Dolphin Evolution”, April 25, 2017. Dolphins-World

- ↑ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3686761/ Mariana F. Nery, Dimar J. Gonzalez, and Juan C. Opazo, “How to Make a Dolphin: Molecular Signature of Positive Selection of Cetacean Genome” 2013. National Center for Biotechnology Information

- ↑ Carroll SB “Chance and Necessity: The evolution of morphological complexity and diversity” 2001. Nature 409: 1102-1109

- ↑ Hill DA, Reynolds JE “Gross and microscopic anatomy of the kidney of the West Indian manatee, Trichechus manatus (Mammalian: Sirenia), 1989. Acta Anat 135: 53-56

- ↑ https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/earth-and-planetary-sciences/dolphin Bruno Cozzi and Helmet Oelschlager “Urinary System, Genital systems, and Reproduction” 2017. Anatomy of Dolphins

- ↑ Hill DA, Reynolds JE “Gross and microscopic anatomy of the kidney of the West Indian manatee, Trichechus manatus (Mammalian: Sirenia), 1989. Acta Anat 135: 53-56

- ↑ https://jeb.biologists.org/content/205/22/3475 Erin M. Meagher, William A. McLellan, Andrew J. Westgate, Randall S. Wells, Dargan Frierson, Jr, D. Ann Pabst “The relationship between heat flow and vasculature in the dorsal fin of wild bottlenose dolphins Tursiops truncatus 2002. Journal of Experimental Biology

- ↑ https://www.healthline.com/health/muscular-hypertrophy Daniel Budnis “Muscular Hypertrophy and Your Workout” 2019. Healthline

- ↑ Kooyman GL “Diving physiology” 2008. Ln: Perrin MR, Wursig B, Thewissen JGM, editors. Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals San Diego: Academic Press, pp 327-332

- ↑ Kooyman GL “Diving physiology” 2008. Ln: Perrin MR, Wursig B, Thewissen JGM, editors. Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals San Diego: Academic Press, pp 327-332

- ↑ https://us.whales.org/whales-dolphins/how-do-whales-and-dolphins-breathe/ Whale and Dolphin Conservation “How Do Dolphin and Whales Breath?” 2019. Whale and Dolphin Conservation

- ↑ Wang Z, yuan L, Rossiter SJ, Zuo X, Ru B, et al. “Adaptive evolution of 5’HoxD Genes in the origin and diversification of the Cetacean flipper” 2009. mol Biol Evol 26: 613-622

- ↑ Mass AM, Supin AYA “Adaptive features of aquatic mammals’ eye” 2007. Anat Rec 209 The genes give access to the eyes to various benefits.: 701-715

- ↑ https://dolphins.org/physiology Dolphin Research Center “physiology” 2019. Dolphin Research Center

- ↑ Mass AM, Supin AYA “Adaptive features of aquatic mammals’ eye” 2007. Anat Rec 209 The genes give access to the eyes to various benefits.: 701-715

- ↑ Oeschlager HHA “The dolphin brain - a challenge for synthetic neurobiology” 2008. Bran Res Bull 75: 450-459

- ↑ Adan PJ “Hind limb anatomy” 2008. Ln: Perrin MR, Wursig B, Thewissen JGM, editors. Encyclopedia of Marina Mammals. San Diego: Academic Press. Pp 562-565.

- ↑ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3686761/ Mariana F. Nery, Dimar J. Gonzalez, and Juan C. Opazo, “How to Make a Dolphin: Molecular Signature of Positive Selection of Cetacean Genome” 2013. National Center for Biotechnology Information

- ↑ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3686761/ Mariana F. Nery, Dimar J. Gonzalez, and Juan C. Opazo, “How to Make a Dolphin: Molecular Signature of Positive Selection of Cetacean Genome” 2013. National Center for Biotechnology Information

- ↑ https://dolphin-academy.com/learn/evolution Bapor Kibra, Willemsted, and Curaçao “Learn About Dolphin Evolution” 2019. Dolphin Academy

- ↑ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3686761/ Mariana F. Nery, Dimar J. Gonzalez, and Juan C. Opazo, “How to Make a Dolphin: Molecular Signature of Positive Selection of Cetacean Genome” 2013. National Center for Biotechnology Information

Edited by [Carolyn Herbosa], student of Joan Slonczewski for BIOL 116 Information in Living Systems, 2019, Kenyon College.