Salmonella enterica serovar Paratyphi

Etiology/Bacteriology

Taxonomy

| Domain = Bacteria

| Phylum = Proteobacteria

| Class = Gammaproteobacteria

| Order = Enterobacteriales

| Family = Enterobacteriaceae

| Genus = Salmonella

| species = S. enterica

| subspecies = enterica, serovar Paratyphi A, B, and C

{|NCBI: Taxonomy Genome: Genome|}

Description

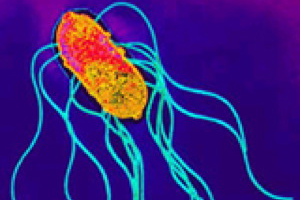

Salmonella enterica are motile, non-lactose fermenting, non-spore forming, Gram-negative rods that can ferment glucose with production of acid and gas[1] . In the subspecies, enterica, there are three serotypes, Paratyphi A, B, and C. These serotypes are human pathogens that cause paratyphoid fever. Cases of disease with Paratyphi A and B are more prevalent than infection from Paratyphi C. In the United States, paratyphoid fever is uncommon, while, an estimated 5.4 million outbreaks occurred in East Asia in 2000. Salmonella enterica serovar Paratyphi, also referred to as Salmonella Paratyphi, causes 3% of invasive Salmonella infections in the U.S and is correlated to poor sanitation and lack of clean drinking water; therefore, prevention entails basic sanitation and education[2]. Symptoms of paratyphoid fever typically include fever peaking around 40°C, red rash covering the trunk, constipation, severe stomach pain, and loss of appetite. Diagnosing paratyphoid fever is difficult for many health care providers. Although the disease can sometimes be detected through a simple blood culture, a more accurate examination for the disease can be found by a bone marrow culture. Paratyphoid fever and typhoid fever are clinically indistinguishable, thus treatment of the paratyphoid fever is similar to the treatment of typhoid fever. Specific antibiotics can shorten the course of the fever and reduce the chances of death. Paratyphi A infections lead to complications in 10-15% of the cases, such as meningitis, endocarditis, hepatic absess, gall bladder cancer, and pancytopenia[2]. Upon infection by Salmonella Paratyphi, the immune system mounts a humoral response predominately producing and utilizing IgA antibodies. Research indicates that a cell-mediated response is also employed. There are currently no vaccines to prevent Salmonella Paratyphi ; however, studies are being conducted concerning the efficacy of the Salmonella Typhi Ty21a-vaccine providing protection from Salmonella Paratyphi as well.

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis mechanisms of Salmonella paratyphi bacterium are not completely understood, but there are several key features of the bacterium's ability to infect and colonize the human host. The bacterium is able to survive the low pH of the stomach and enter the intestines. The mechanism which Salmonella Paratyphi uses in order to adhere to the epithelial cells of the intestines are unknown. Paratyphi B specifically utilizes mechanisms which enable it to cross the intestinal walls and survive in host tissue. A high affinity for iron-uptake utilizing siderophores may also be important regarding the pathogenicity of this particular bacterium. [3]

Transmission

Salmonella enterica serovars Paratyphi is transmitted primarily through humans, although there are rare cases of transmission from domesticated animals. The pathogen is most frequently encountered through the ingestion of water, contaminated with feces from an infected individual or an asymptomatic carrier of the disease. Milk, raw vegetables, salads, shellfish, and ice can also transmit the pathogen if not properly washed or prepared. Also, there are rare reports of the disease being transmitted sexually. [4]

Infectious dose, incubation, and colonization

The infectious dose of Salmonella Paratyphi is generally greater than 1000 organisms. The incubation period of gastroenteritis caused by Salmonella Paratyphi is between one and ten days, however, the incubation period for enteric fever caused by Salmonella Paratyphi is longer, lasting between one and three weeks. Salmonella Paratyphi colonize the intestines, but this can be buffered by stomach acidity. This defense necessitates a greater number of bacteria to be ingested in order to result in symptomatic infection. [5]

Epidemiology

Paratyphoid fever generally occurs sporadically or in contained outbreaks. Approximately six million cases of Paratyphoid fever are reported annually throughout the world. In the United States approximately one hundred cases are reported, with most occurring in recent travelers. The risk of Paratyphi A is most preeminent in South and Southeast Asia. Southern Asia presents the highest risk of contracting nalixidic acid resistant paratyphoid fever, as well as multidrug resistant paratyphoid fever. Antibiotic resistant strains of paratyphoid fever are resistant to ampicillin, chloramphenicol, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. [4] [5]

Virulence factors

The virulence factors of Salmonella paratyphi are predominantly the same as those of other Salmonella enterica serotypes. Two of the major virulence factors include the Salmonella pathogenicity Islands I and II. SPI1 encodes genes which contain a type III secretion system. This system allows the pathogen to inject effector proteins directly into the host cell's cytoplasm, and aids in the bacterial invasion of epithelial cells. SPI2 has roles in bacterial replication while within a Salmonella-containing vacuole. SPI2 also encodes for a type III secretion system. [6] [7]

Another important virulence factor is found particularly in Paratyphi A. Cytolysin A (ClyA) is a cytotoxic protein which forms pores in membranes. It is a virulence factor most commonly attributed to Escherichia coli, but the gene has been found to be conserved in many Salmonella enterica species. [8]

Several studies have been done to investigate different plasmids present in Salmonella enterica serotypes. Their role in virulence is not well understood, but studies have shown that Paratyphi C contains a large cryptic plasmid, which is thought to play some role in the virulence of the strain. [6]

Clinical features

Symptoms

Paratyphoid fever is very similar to typhoid fever and they are often mistaken for one another; however, symptoms of paratyphoid fever have been known to be less severe because the infection is not nearly as extreme as typhoid fever. Symptoms from paratyphoid fever usually occur between 6-30 days after being infected. The most common, and perhaps prominent, symptom is severe fatigue accompanied by a fever. The fever typically presents as low-grade and can rise as high as 40°C in the third and fourth days of the illness. Additional symptoms that commonly appear are headache, a distinct, red rash all over the trunk, cough, stomach pain, loss of appetite, and constipation or severe diarrhea [9] [10] [11]

Morbidity/Mortality

Once treated, approximately 10% of those with paratyphoid fever will continue to secrete S. paratyphi in their stool for up to three months, which could then be passed on to infect others. Around 2-3% of the recovering patients become permanent carriers for the disease [10]. Paratyphoid fever was once a major cause of mortality throughout the world; however, the infection has begun to be eradicated through various prevention mechanisms. Nevertheless, the disease is still a problem in tropical and underdeveloped countries of the world, typically Africa, Latin America, and South-Eastern Asia. Although the findings are some what inconclusive, it is believed that approximately 5.4 million cases of paratyphoid fever occur every year [12].

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of paratyphoid fever can be confirmed by a culture of the blood or bone marrow. As the disease progresses, blood bacterial counts decline which make the blood cultures positive in only about 40-60% of cases. The validity of the test can be increased to 80% if multiple sets of blood cultures are taken. The most accurate way to test for paratyphoid fever is by a bone marrow culture because bacterial counts are typically ten times higher in the bone marrow than in a blood culture. An additional test to diagnose the disease is to perform a biopsy on the rose-colored rash on the trunk of the patient. [10]

Treatment

Paratyphoid fever is treated with specific antibiotics to shorten the course of paratyphoid fever and decrease the chance of death. In most parts of the world ciprofloxacin, a fluoroquinolone, is used to combat the disease. In Indian countries where cases of Paratyphoid fever are more prevalent, health officials use cephalosporins for treatment due to increased resistance towards fluoroquinolones and nalidixic acid. Azithromycin is also more commonly used due to the increase of multi-drug resistant strains. After treatment, three to five days may be required for the antibiotic to resolve the fever completely. Some patients feel worse during the several days of waiting for the fever to end, however, the height of the fever decreases each day. If the fever does not resolve within five days, alternative antibiotics should be considered [13].

Prevention

Risk Avoidance

The incidence of enteric fever is most strongly correlated with poor sanitation and lack of clean drinking water. This is because Salmonella Paratyphi is transmitted through consumption of contaminated food or water. In order to decrease the incidence of this disease it is important to avoid the consumption of contaminated food or water, provide education about food and water safety, and promote basic sanitation. [14] [12]

Immunization

There are currently no vaccines clinically used to defend against Salmonella Paratyphi [12] . Recent studies have indicated that this organism displays evidence drug resistance. For example, it was discovered that Salmonella Paratyphi has limited sensitivity of ofloxacin, nalidixic acid, and ciprofloxacin. [14]

Because of the evidence for drug resistance, Salmonella Paratyphi poses a potential health risk and there is a growing necessity for the development of an effective vaccine. There have been studies on the potential use of an oral vaccine that would be used to prevent Salmonella Paratyphi infections, as well as avert typhoid fever. The oral live Salmonella Typhi Ty21a-vaccine has been shown to offer some protection against Salmonella Paratyphi B, slightly less protection against Salmonella Paratyphi A, and no protection against Salmonella Paratyphi C. [12] These varying levels of prevention are due to differences in the shared epitopes of each strain. Despite the research that has been done, there are still no vaccines currently being used in a clinical setting.

Host Immune Response

When the body is infected by Salmonella Paratyphi, a humoral immune response is mounted. The response primarily takes place in the intestinal tract, since the gut is the first line of defense against enteric diseases [15]. Based on research performed with the Ty21a-vaccine, after the host was exposed to the oral vaccine there was a predominance of IgA antibodies. As part of the immune response, it is believed that after the B cells arrive in the intestinal lining, they undergo isotype switching from IgM to IgA. This specific immunoglobulin isotype is produced to stimulate the destruction of Salmonella bacteria. Other research indicates that a cell-mediated response is also activated upon infection. [12]

References

1 E. Umeh, C. Agbulu. Distribution Pattern Of Salmonella Typhoidal Serotypes In Benue State Central, Nigeria. The Internet Journal of Epidemiology

http://ispub.com/IJE/8/1/5749

2 Sundeep K. Gupta, et al. Laboratory-Based Surveillance of Paratyphoid Fever in the United States: Travel and Antimicrobial Resistance. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 46(11):1656-1663 http://cid.oxfordjournals.org/content/46/11/1656.full

3 Chart, H. The pathogenicity of strains of Salmonella paratyphi B and Salmonella java. Journal of Applied Microbiology. 94:340-348. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1046/j.1365-2672.2003.01863.x/pdf

4 Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC). Salmonella Paratyphi. Infectious Disease Index. http://www.msdsonline.com/resources/msds-resources/free-safety-data-sheet-index/salmonella-paratyphi.aspx

5 Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Typhoid and Paratyphoid Fever. Traveler’s Health. http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2014/chapter-3-infectious-diseases-related-to-travel/typhoid-and-paratyphoid-fever

6 Ibarra, J Antonio and Steele-Mortimer, Olivia. Salmonella – the ultimate insider, Salmonella virulence factors that modulate intracellular survival. Cellular Microbiology. 11 (11): 1579-1586. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2774479/

7 Lin, Dongxia, Rao, Christopher V., Slauch, James M. The Salmonella SPI1 Type Three Secretion System Responds to Periplasmic Disulfide Bond Status via the Flagellar Apparatus and the RcsCDB System. Journal of Bacteriology. 190(1):87-97. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2223759/

8 Oscarsson, Jan et al. Characterization of a pore-forming cytotoxin expressed by Salmonella enterica Serovars Typhi and Paratyphi A. Infection and Immunity. 70(10): 5759-5769. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC128311/

9 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Infectious Diseases Related to Travel – Typhoid and Paratyphoid Fever. Available at http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2014/chapter-3-infectious-diseases-related-to-travel/typhoid-and-paratyphoid-fever.

10 White, Nicholas J.: Salmonella typhi and S. paratyphi. Antimicrobe 2010.

11 Government of Western Australia Department of Public Health. Typhoid and Paratyphoid fact sheet. Available at http://www.public.health.wa.gov.au/2/601/2/typhoid_and_paratyphoid_fact_sheet.pm#C, 2014.

12 Pakkanen SH, Kantele JM, Kantele A: Cross-reactive gut-directed immune response against Salmonella enterica serovar Paratyphi A and B in typhoid fever and after oral Ty21a typhoid vaccination. Vaccine 2012, 30: 6047-6053.

13 CDC. Traveler’s Health: Typhoid and Paratyphoid Fever. Available at http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2014/chapter-3-infectious-diseases-related-to-travel/typhoid-and-paratyphoid-fever

14 Maskey AP, et al: Salmonella enterica Serovar Paratyphi A and S. enterica Serovar Typhi Cause Indistinguishable Clinical Syndromes

in Kathmandu, Nepal. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2006, 42: 1247-53.

15 Rezwanul W, et al: Live Oral Typhoid Vaccine Ty21a Induces Cross-Reactive Humoral Immune Responses against Salmonella enterica Serovar Paratyphi A and S. Paratyphi B in Humans. Clinical and Vaccine Immunology 2012, 19(6): 825-834.

Created by MaKenzi Burke, Madeline Gabe, Regina Swenton, and Jordan Voth, students of Tyrrell Conway at the University of Oklahoma.