Yellow fever virus

Etiology/Bacteriology

Taxonomy

ICTV Virus Classification

| Order = Unassigned | Family = Flaviviridae | Subfamily Unassigned | Genus = Flavivirus | Species = Yellow fever virus

Baltimore Classification

| Group= IV | Family = Flaviviridae | Subfamily Unassigned | Genus = Flavivirus | Species = Yellow fever virus

Description

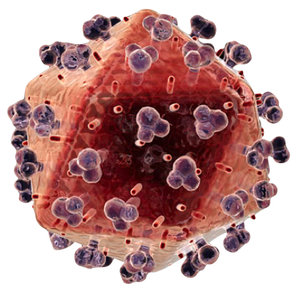

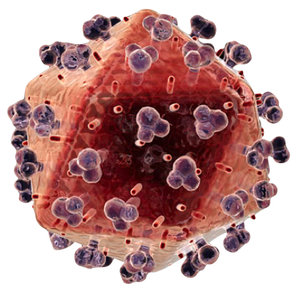

Yellow fever virus (YFV) was the first proven human-pathogenic virus in 1927[1] ; it is a Group IV positive-sense single stranded RNA virus due to its direct mRNA-like functions in a host cell [2]. It belongs to the family Flaviviridae and genus Flavivirus. Yellow fever virus was the first classified in both of these taxonomies, hence the “flavi” Latin root for “yellow”. Arthropod vectors are the main source for the spread of Yellow fever virus (e.g. mosquitos) like many other viruses in the Flaviviridae family (e.g. Hepatitis). There is a great deal of symmetry involved in the near spherical structure of YFV, similar to the other Flavivirus (e.g. Dengue, West Nile). YFV was named for the disease it causes in humans, Yellow fever. Humans are a dead-end host, terminating the virus’s life cycle and consequently suffering from much harsh symptoms than its native host.

Historical Overview

Yellow Fever, as a disease, took notable attention beginning in Philadelphia in 1793, killing 9 percent of the population, again in 1878 along the Mississippi with a death toll of 20,000, and the last major outbreak in the United States occurred in New Orleans in 1905 with 452 deceased [3]. The rapid decrease in outbreaks is attributed to the work of the US Army Medical Corps Yellow Fever Commission led by the Virginian physician Walter Reed during the Spanish-Cuban-American War. Reed used the work of Cuban scientist Carlos Finlay to prove the role of mosquitos, particularly Aedes aegypti, in transmitting the disease (what he believed at the time to be bacterial) and thus was able to develop sanitation techniques in reducing the mosquito population [4]. Infected individuals are characterized by general flu-like symptoms that in 15% of cases develop into the more toxic phase; the disease accounts for 200,000 incidents with 30,000 deaths a year [5].

Pathogenesis

Transmission/Reservoirs

Yellow fever virus (YFV) is transmitted via the mosquito vectors, Aedes and Haemagogus sps, and is endemic in many primate communities. However, humans are a dead-end host for the virus and fail to allow it to complete its life cycle. YFV transmission follows three distinct cycles: sylvatic (jungle) involving mosquitos transmitting virus through monkey intermediates to other mosquitos with the occasional human infection, intermidate (savannah) involve humans and monkeys surviving as intermediates with minor outbreaks occurring, and urban cycles, the largest of epidemics where infected humans introduce the virus to new mosquito population and non-immune people [5].

Incubation/Colonization

Yellow fever virus enters through the bite of a mosquito where it can remain dormant for 6 to 8 days causing massive viremia or quickly infects host cells, including dendritic cells of the lymph nodes and begin the acute stages of disease [2]. The virus enters its host via receptor-mediated endocytosis and then utilizing its mRNA-like structure begins protein synthesis in the host’s endoplasmic reticulum so that it can begin viral replication in the cytoplasm [6].

Epidemiology

Yellow fever virus is endemic among primate communities in sub-Saharan Africa and South America with intermittent epidemics in the countries around those areas[2]. This includes a total of forty-four endemic countries, with a combined population of nearly one billion. With 90% of infection occurring in Africa, it has been estimated that in 2013 120,000 cases and 45,000 deaths occurred in Africa alone[5]. Over time acquired immunity can occur which leads to an increased risk of contracting the disease among infants and children [2].

Virulence Factors

Yellow fever virus’s surface macromolecules are its main virulence factors and contribute to the entry, signaling and cell-cell interactions of the virus. The flavivirus E protein has many functions, but its role in binding and, fusion and cell entry is most important. The genome of the YFV has two distinct non-coding regions; the 3' NCR of these regions is a control mechanism for the virus's replication and level of virulence. The number of repeats and the point mutations within it have been found to effect the virus [7].

Clinical Features

Yellow fever virus (YFV) is distinct from other viral hemorrhagic fevers by the severe injury to the liver causing the namesake jaundice appearance in victims [7].Besides the liver complications. YFV is very similar to other viral infections, beginning with very minor flu-like symptoms early on that can progress to severe a more toxic stage. The toxic stage occurs in 15% of victims involving the jaundice described above, as well as deterioration of kidney function and internal bleeding [5]. Victims of YFV will either die or recover with substantial organ damage between the fifth and tenth day [7].

Diagnosis

Yellow Fever is difficult to diagnose and is often only recognized in its advanced stages, unless the physician has extensive knowledge of the patients travels and detailed history of events that transpired abroad. The first diagnosis comes from neutropenia, the decrease in circulating neutrophils, via laboratory blood testing. If jaundice appears early this indicates a poor prognosis. Blood in urine or feces, as well as, liver dysfunction. In the later stages of the disease, MODS develops [6].

Treatment

There is no primary treatment for Yellow Fever, only secondary, supportive care exists. Secondary care in an intensive care unit is required for complete care. Victims require constant hydration, as well as, treatment for disseminated intravascular coagulation, hemorrhage,renal and hepatic dysfunction. Secondary Infections are also very common among Yellow Fever patients. The most severe cases may require intubation due to the significant hemorrhage [6].

Prevention

Vaccination

The most important prevention of Yellow Fever is through vaccination. When outbreaks begin it is important to have widespread vaccination. In more developed areas the need for vaccination only exists for this e traveling in Yellow Fever" Hot Spots." The Yellow Fever vaccine is 99% effective within the first 30 days and provides life-long immunity [5]. Vaccination is not recommended unless deemed necessary due to severe adverse effects of the vaccine [2].

Mosquito Control

The first method used at combating Yellow Fever was pest control, which is still very effective where vaccination is not cost effective. The use of pesticides in areas where shallow water accumulates can often halt a potential epidemic. It should be noted mosquito control is only feasible for the Urban cycle of transmission and not for the Jungle or Savannah cycles [5].

Host Immune Response

Yellow fever virus, due to its injection via mosquito, is believed to first encounter the immune system via dendritic cells. Thus the cascade of nonspecific immune responses begin. NK cell and interferons are the most prominent immune responses in controlling YFV replication. Once cytotoxic T cells and antibodies have been made they further the immune response. Only one in seven infected with YFV develop the disease indicating that the innate immune response is often enough to combat the pathogen. However, research has shown that YFV can promote the expression of MHC I a natural deterrent for NK cells. Neutralizing antibodies develop after 7-8 days into the infection and make up part of the humoral immune response. The NS1 protein from YFV is the main target for antibodies [7].

References

- Stock NK, Laraway H, Faye O, Diallo M, Niedrig M, Sall AA. Biological and phylogenetic characteristics of yellow fever virus lineages from West Africa. J Virol. 2013 Mar;87(5):2895-907. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01116-12. Epub 2012 Dec 26. PubMed PMID: 23269797; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3571399.

- CDC. Yellow Fever. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011 Dec. 13. Web.

- PBS PBS. The Great Fever. PBS. PBS, 2006 Sept. 29. Web.

- University of Virginia. Yellow Fever Commission. Philip S. Hench Walter Reed Yellow Fever Collection. University of Virginia, The Claude Moore Health Sciences Library, 2004 Feb. 24. Web.

- WHO. Yellow Fever. WHO. WHO Media Centre, 2014. Mar. Web.

- Busowski, Mary T. Yellow Fever . Ed. Burke A. Cunha. Medscape. 2014 May 2. Web.

- Chambers, Thomas M., Aaron J. Monath, Karl Maramorosch, Frederick A. Murphy, and Aaron J. Shatkin. Advances in Virus Research. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2003.