Granuloma inguinale

Overview

By Emma Mairson

Granuloma inguinale (also known as donovanosis) is a sexually transmitted disease caused by the Klebsiella granulomatis bacteria. The pathogenic bacteria was formerly called Donovania granulomatis and Calymmatobacterium granulomatis [1].

History

In 1882 in Madras, India, K. McLeod first described granuloma inguinale. He called it serpiginous ulcer, referring to the wavy margins of the symptomatic sores. However, it was Donovan in 1905 who first demonstrated and described the causative agent, which is why they are now known as Donovan bodies [2]. In 1913, Aragao and Vianna published a well-established work regarding the etiological agent, and proposed naming the bacteria Calymmatobacterium granulomatis. During the present century, the names Donovania granulomatis and Klebsiella granulomatis were also proposed. Then, in 1943, Anderson established that the Donovan bodies were bacterial in nature. In his experiment, he cultivated the microbe in a vitelline embryonic yolk sac. In 1950, Marmell and Santora suggested the name Donovanosis in reference to the disease’s characteristic Donovan bodies [3].

Prevalence

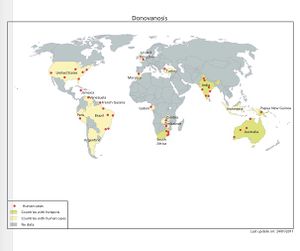

In the United States, fewer than 100 cases are reported each year [4]. Internationally, however, in tropical and subtropical countries, granuloma inguinale is much more common. In fact, the disease is endemic in Western New Guinea, the Caribbean, Southern India, South Africa, Southeast Asia, Australia (particularly among aboriginals), and Brazil [4]. Though granuloma inguinale does have differential racial and geographic prevalence, this is likely due to both hygienic and socioeconomic factors.

Transmission

Granuloma inguinale is transmitted mostly through vaginal and anal intercourse and rarely through oral sex. The disease can also be transmitted through ingestion of fecal matter of an infected person or passage through an infected birth canal. It has been hypothesized to have low infectious capabilities as clinical infection usually occurs only after repeated exposure.

Risk groups include homosexual men, sex workers, and young patients. Pregnant women, women who have had a hysterectomy, and patients who have had known contact with the infection are also at risk [1].

The proposed sexual mode of transmission is slightly controversial, however. Children who are not sexually active, non-infected spouses of infected patients, and the localization of ulcers in regions typically unrelated to sexual intercourse call into question the resolute assumption that granuloma inguinale is sexually transmitted [2]. Infection rates among conjugal partners has been reported to be anywhere from 0.4% to 52% [5].

Symptoms and Diagnosis

Symptoms can manifest anywhere from 1 to 12 weeks after exposure to Klebsiella granulomatis. However, they can take as long as a year to develop. The primary symptom is puffy dark red genital or anal sores. About half of granuloma inguinale-infected men and women will develop anal sores [6]. The sore starts as a bump. As the skin wears away, the bumps become beefy-red nodules of granulation tissue. The surrounding skin can also lose color. The sores are typically not painful but are prone to bleeding if disturbed. Though the disease progresses slowly, it can destroy genital tissue and the damage can ultimately spread to tissue in the inguinal folds. If the disease is allowed to progress to its late stages, permanent tissue damage and scarring and genital swelling due to scarring can occur [6].

In order to be classified as a granuloma-inguinale-caused lesion, the sore itself can have several distinct features. The ulcer can be located in the genital or surrounding region. It can be ulcerous, meaning that it is an open sore on a surface of the body. The ulcer can exhibit hypertrophic edges, meaning that any enlargement must exist within the boundaries of the ulcer. Most commonly, it can be ulcerovegetating. These lesions are typically painless, large, expanding, and pus-producing. They have clean edges with distinct, raised, rolled margins and tend to bleed very easily [7]. The border frequently expands along the folds in skin. They can also be vegetating, meaning that the ulcer is resting and not active. Elephantiasis of the genitals is another characterizing symptom. Though these symptoms are common in patients with donovanosis inguinale, it can present in odd ways, which makes diagnosis and treatment more difficult. As with any infectious disease, but especially with HIV-positive and AIDs patients, the clinical development of the disease can be entirely abnormal [2].

Extragenital presentation of ulcers occurs in 6% of granuloma inguinale cases. Self-infection or extension of the ulcer can occur and may lead to development of the infection on the lips, oral or gastrointestinal mucosa, scalp, abdome, arms, legs, and bones. Disease of the lymph nodes can occur not as a result of granuloma inguinale infection but as a secondary complication of a subsequent bacterial infection. In systemic cases that are frequently reported in endemic regions, the disease can be carried from the lesions, through the blood, and infect the spleen, lungs, liver, and bones. This only occurs occasionally but can result in death [7].

Granuloma inguinale presents slightly differently in men and women. Women often develop lesions in the labia minora, the mons veneris, the fourchette, and/or the cervix [7]. In addition to large, fungating labial ulcers, women infected with granuloma inguinale at its late stages can experience elephantiasis labial swelling, unusual vaginal discharge, rectovaginal fistulae and hematuria [8]. For men, the lesions present themselves in the sulcocoronal and balanopreputial regions of the penis.

In the earlier stages of the disease, granuloma inguinale can be mistaken with chancroid, which also causes ulceration in the genital region. Later stages of the disease have common features with genital cancer, lymphogranuloma veneer, and anogenital cutaneous amebiasis [6]. It can also be confused with herpes and syphilis. Granuloma inguinale causes sores that persist and spread, a feature which can be useful in distinguishing it from other diseases. Exploring the possibility that symptoms are caused by another sexually transmitted disease should be considered when making a diagnosis.

Several tests can be run to confirm that particular genital ulcers were the result of Granuloma inguinale. Tissue samples can be cultured, however this is difficult to do and is beyond the capabilities of most laboratories. Typically lab tests, such as polymerase chain reaction, to diagnose are only run on a research basis. Most commonly, a scraping or punch biopsy and the use of special stains can also be used to diagnose [6]. The best sites to collect samples to be tested are at the base or edge of the sore, or from the regional lymph nodes especially if the testing the ulcer itself for granuloma inguinale yields negative results [1]. The Klebsiella granulomatis organism exhibits bipolar staining and are referred to as Donovan bodies. Smearing is another method that can be used if a fast diagnosis is necessary. Gently, so as to avoid inducing bleeding, a cotton swab is swiped over the lesion. The swab is then wiped on a glass slide. After drying, the slide is stained using Giemsa stain or pinacyanol to visualize the Donovan bodies [9]. An alternative diagnosis technique is crush preparation. A sample of tissue is obtained and is then sandwiched between two glass slides, and separated. In order to demonstrate the Donovan bodies, the sample can be stained using Wright-Giemsa, Warthin-Starry, toluidine blue, or Leishman stain [9].

Treatment

In order to cure granuloma inguinale, a long term course of antibiotics must be prescribed. Typically the regimen will be about 3 weeks long or until the ulcers have healed completely. It is important to note, however, that although the drug therapy may have seemed to work and symptoms may appear to be gone, granuloma inguinale can remain dormant and then reemerge anywhere from 6 to 18 months later [10]. In this case, a drug regimen should be started again. Starting treatment earlier reduces the risk of permanently damaging genital or surrounding tissue – which can occur in later stages of the infection. In the case that permanent disfigurement occurs, surgical options may be recommended.

Antibiotics work well against the Klebsiella granulomatis bacteria because it is gram negative and its lipid solubility allows for good intracellular penetration. The drug of choice, according to the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in treating suspected or confirmed granuloma inguinale is azithromycin [11]. It is recommended that if the ulcers do not begin to respond during the first few days of therapy, aminoglycoside should be added [10]. This is also highly recommended for patients with HIV-associated granuloma inguinale [10]. Other drugs that have been used to treat the disease include streptomycin, chloramphenicol, erythromycin base, lincomycin, cotrimoxazole, norfloxacin, thiamphenicol [11], ciprofloxacin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole [10]. Tetracycline was at one point recommended but has been found to be capable of antibiotic resistance and thus is no longer a recommended treatment.

A 2007 study in Brazil gave 10 male patients infected with granuloma inguinale a treatment of 2.5 g oral thiamphenicol for two weeks. The diagnosis of granuloma inguinale was confirmed through tissue staining with Giemsa. During the first follow-up examination, all patients demonstrated reduction and regression of the ulcer. For eight of the ten patients, including two that were infected with HIV, the lesions healed. For the other two cases where the ulcers persisted, the patients were immediately given a dose of 1 g azithromycin followed by 500 mg every day for the next two weeks. There was no recurrence of the disease after the 90 day follow-up period. The authors proposed thiamphenicol as a cost-effective and useful agent in the cure of granuloma inguinale [12].

The CDC’s 2015 Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines includes recommended dosages for common antibiotics prescribed for granuloma inguinale. For all antibiotics, the patient should continue with the regiment for at least 3 weeks or until the ulcers have healed. The recommended regimen of azithromycin is 1 g orally once a week or 500 mg every day. For doxycycline, 100 mg two times a day is recommended. Ciprofloxacin should be taken as two 750 mg doses per day. Erythromycin base should be taken four times a day in 500 mg doses. Finally, one double-strength (160 mg/800 mg) pill of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole should be taken twice per day [13]. In order for the treatment to work properly, adherence to the prescribed drug regimen is absolutely necessary to ensure a cure.

When prescribing for pregnant women, erythromycin or azithromycin, the macrolides, are recommended. Because erythromycin has been found to cause hepatotoxicity in up to 10% of pregnancies, erythromycin base or erythromycin ethylsuccinate are recommended. Doxycycline is also not recommended for pregnant women, especially after 15 weeks of pregnancy. This antibiotic can cause hepatitis in the mother, inhibition of the infant’s bone growth, and brown coloration of the infant’s deciduous teeth. Additionally, ciprofloxacin should not be prescribed to pregnant women as it has been known to cause damage to fetal cartilage. It is also advised to look out for diarrhea in an infant who is breastfeeding from a mother on ciprofloxacin. This could be a sign that the infant has developed pseudomembranous colitis, an inflammation of the colon. Finally, a mother in her first trimester on trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (a combination of a sulfonamide antibiotic and a methoprim) is at risk of birthing an infant with cardiovascular defects. Other possible complications include preterm birth, low birth rate, and miscarriage. Additionally, if a pregnant woman who has a glucose-6-phosphate-dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency and is prescribed a sulfonamide, she is at risk for a serious brain dysfunction known as kernicterus. If she is in her third semester of pregnancy, her infant could be at risk for developing neonatal hyperbilirubinemia. Trimethoprim can decrease folate levels so it is important, especially during the first semester of a woman’s pregnancy, to take folate supplements if she is on this treatment [10].

Prevention and Follow-up

The only completely effective way to prevent transmission of any sexually transmitted disease, including granuloma inguinale, is to avoid all sexual activity. It is especially important to avoid sex with someone who has visible genital sores. However, the use of condoms during vaginal or anal sex can decrease the risk of transmission. Condoms must be worn throughout the entire sexual act. Additionally, while it does not change risk, early detection by testing for the disease can give an infected person the opportunity to practice safe sex.

In Australia, where granuloma inguinale is endemic, much progress has been made in decreasing the number of cases of the disease. Established in 2001, the National Donovanosis Eradication Advisory Committee connects project officers representing different geographic regions with primary health-care providers. The committee’s goals include the development of educational materials, the education of staff in rural and remote areas, the implementation of uniform protocols in treating and diagnosing granuloma inguinale and the surveillance of the spread of the disease. Since the committee was created, the number of new cases of the disease has fallen the lowest levels that have ever been accurately recorded. This success of this model, connecting project managers very knowledgeable on granuloma inguinale and primary care doctors, has been recommended for other areas where the disease is endemic [14].

Additional precautions may be taken upon receiving a diagnosis of granuloma inguinale. It is wise to avoid sexual contact for seven days after beginning the treatment. It is also wise to avoid sex with any sexual partners from the past six months until they, too, have been tested and treated. In order to prevent further spread of the disease, figuring out how the patient was infected may be important.

When following up with infected patients, physicians should be on the lookout for possible complications. One of the most serious of these complications is carcinoma, cancer of the epithelial tissue. This has been reported to occur in 25 of every 10,000 patients (0.25%). Thickening and scarring of the underlying genital tissue can also be a permanent complication. Male patients may also develop phimosis, the narrowing of the opening of the foreskin so much that it can no longer be retracted. Functional disability may also occur. If lymphatic destruction has taken place, patients can develop elephantiasis, or an extreme swelling, of the genitals. Development of granuloma inguinale can increase a patient’s risk of acquiring HIV. This risk is made worse if the lesions are chronic [15]. During a one week follow up, it is important for the doctor to ensure that the patient is properly adhering to their treatment regimen and check to see that symptoms are resolving. They should also check that contact tracing is being carried out. Additional sexual health education, including prevention education, could also be done at this time.

Due to the higher prevalence in regions of Australia and Asia, a Australasian Contact Tracing Manual has been devised. The manual advises to trace back a variable amount of time depending on sexual history and when the patient was last tested. Because the likelihood of transmission through unprotected sex is low, contact of regular partners should prioritized above casual partners [16].

Individual Case Reports

One reported case involved a HIV-2-infected 30-year-old male who neglected an ulcer he had developed on his penis for a year and his penis had auto-amputated. He was an alcoholic and had engaged in both unprotected and protected premarital and extramarital sex. Six years prior, he had developed an ulcer on his penis and after a year, the penis fell off [17].

In one case, a 50-year old female had a painless ulcerative growth that bled when touched. She had had the ulcer for 5 years. Initially, the issue had been a small skin lesion on her left labia but it eventually developed into ulceration of the entire vulva. Married for 30 years, she denied any extramarital affairs and her husband had never presented any genital ulcers. Inspection of the ulcer revealed that it extended from the clitoris to the fourchette, a thin fold of skin at the back of the vulva and encompassed the entire left labia. After staining of a tissue smear confirmed the presence of Donovan bodies, the patient was put on a dose of 100 mg of doxycycline for two weeks. This did not improve her condition. After further testing, it was discovered that she had developed squamous cell carcinoma. The patient underwent radical vulvectomy with bilateral inguinal lymphnode block dissection [18].

A married 27-year-old woman presented with a pus in her vaginal discharge that she had been experiencing for a year. Initially she was given anti-fungals, however this only provided temporary symptomatic relief. There was no extramarital or sexual activity so both the patient and her husband were tested for human immunodeficiency virus and were also given the Veneral Diseases Research Laboratory test. A Pap smear was also performed. The Pap revealed the presence of donovan bodies. Noteably, this was an incidental finding in a patient who was being given erroneous treatment [19].

In another case, a patient was thought to have granuloma inguinale but it was, in fact, cutaneous metastases of rectal mucinous adenocarcinoma. A 46-year-old man presented ulcerovegetative lesions in the anogenital region. He had initially noticed the lesions one month prior. Because the patient had a history of travel to Africa, it was assumed that the ulcer was the result of granuloma inguinale. However, when testing of scrapings was performed, Klebsiella granulomatis was not observed. Through histological analysis, it was revealed that the ulcer was actually the result of cutaneous metastasis of mucinous adenocarcinoma of the rectum [20].

An 18-year-old girl came for treatment with an ulcer on her labia that had been present for 8 months. She had decided to seek treatment because the ulcer had grown progressively larger over the course of the past two weeks. Additionally, there had been some enlargement of the right labia which was ulcerated. The ulcers were prone to bleeding upon touch. The patient had a history of unprotected sexual exposure. Based on these symptoms, it was assumed that the patient was infected with granuloma inguinale. Samples were sent for histopathological analysis. The antibiotics prescribed for the granuloma inguinale did not do anything to improve symptoms or cure the disease. Through multiple tests and biopsies, it was revealed that the actual cause of the ulceration and swelling was squamous cell carcinoma. The patient had to undergo a vulvectomy only on one side and ipsilateral inguinal lymph node dissection [21].

References

[1] Richens, J. 2006. Donovanosis (granuloma inguinale). Sexually Transmitted Infections. 82:iv21-iv22.

[2] Borchardt, K.A. and M.A. Noble. 1997. Sexually transmitted diseases: Epidemiology, pathology, diagnosis, and treatment. CRC Press.

[3] Gross, G. and S.K. Tyring. 2011. Sexually transmitted infections and sexually transmitted diseases. Springer Science & Business Media.

[4] Satter, E.K. 2015. Granuloma inguinale (donovanosis): Overview: Epidemiology. Medscape. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1052617-overview#a6

[5] Hart, G. 1997. Donovanosis. Clinical infectious diseases. 25: 24-32.

[6] Vyas, J.M. 2013. Donovanosis (granuloma inguinale). MedlinePlus. https://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/000636.htm

[7] Satter, E.K. 2015. Granuloma inguinale (donovanosis): Presentation: Physical. Medscape. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1052617-clinical#b4

[8] Wysoki, R.S., B. Majmudar, and D. Willis. 1988. Granuloma inguinale (donovanosis) in women. Journal of Reproductive Medicine. 33(8): 709-13.

[9] Satter, E.K. 2015. Granuloma inguinale (donovanosis): Workup: Laboratory studies. Medscape. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1052617-workup

[10] Satter, E.K. 2015. Granuloma inguinale (donovanosis): Treatment: Medical care. Medscape. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1052617-treatment

[11] O’Farrell, N. 2002. Donovanosis. Sexually Transmitted Infection. 78(6): 452-7.

[12] Belda Jr., W., P.E. Neves Ferreira Velho, M. Arnone, and R. Romitti. 2007. Donovanosis treated with thiamphenicol. Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases. 11:4.

[13] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2015. Granuloma inguinale (donovanosis). http://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/donovanosis.htm

[14] Satter, E.K. 2015. Granuloma inguinale (donovanosis): Follow-up: Deterrance/Prevention. Medscape. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1052617-followup

[15] Satter, E.K. 2015. Granuloma inguinale (donovanosis): Follow-up: Complications. Medscape. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1052617-followup#e3

[16] Australasian Contact Tracing Manual. Donovanosis. http://ctm.ashm.org.au/Default.asp?PublicationID=6&ParentSectionID=670&SectionID=674

[17] Chandra Gupta, T.S., T. Rayudu, and S.V. Murthy. 2008. Donovanosis with auto-amputation of penis in a HIV-2 infected person. Indian Journal of Dermatology, Venereology, and Leprology. 74(5): 490-2.

[18] Sri, K.N., A.S. Chowdary, and B.S.N. Reddy. 2014. Genital donovanosis with malignant transformation: An interesting case report. Indian Journal of Sexually Transmitted Disease. 35(2):135-7.

[19] Wahal, S.P., and D. Tuli. 2013. Donovanosis: An incidental finding on Pap test. Journal of Cytology. 20(3): 217-8.

[20] Balta, I., G. Vahaboglu, A.A. Karabulut, F. Yetisir, M. Astarci, E. Gungor, and M. Eksioglu. 2012. Cutaneous metastases of rectal mucinous adenocarcinoma mimicking granuloma inguinale. Internal Medicine. 51: 2479-81.

[21] Agrawal, M., S.K. Arora, and A. Agarwal. 2011. A forgotten disease reminds itself with a rare complication. Indian Journal of Dermatology. 56(4):430-1.

Authored for BIOL 291.00 Health Service and Biomedical Analysis, taught by Joan Slonczewski, 2016, Kenyon College.