The History and Transmission of Treponema pallidum; Syphilis

Classification of Treponema pallidum

• Kingdom: Bacteria

• Phylum: Spirochaetae

• Class: Spirochaetes

• Order: Spirochaetales

• Family: Spirochaetacecae

• Genus: Treponema

The insertion code consists of:

Double brackets: [[

Filename: PHIL_1181_lores.jpg

Thumbnail status: |thumb|

Pixel size: |300px|

Placement on page: |right|

Legend/credit: Electron micrograph of the Ebola Zaire virus. This was the first photo ever taken of the virus, on 10/13/1976. By Dr. F.A. Murphy, now at U.C. Davis, then at the CDC.

Closed double brackets: ]]

Other examples:

Bold

Italic

Subscript: H2O

Superscript: Fe3+

Introduce the topic of your paper. What is your research question? What experiments have addressed your question? Applications for medicine and/or environment?

Sample citations: [1]

[2]

A citation code consists of a hyperlinked reference within "ref" begin and end codes.

Description of Structure and Significance

By: Marcus Townsend

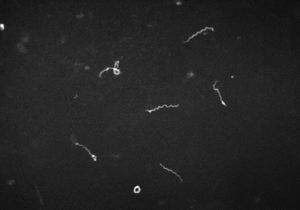

The bacteria Treponema pallidum is a bacteria prominently known for the cause of the chronic sexually transmitted disease syphilis. T. pallidum, also has relatives that are in a subspecies. These trepenomes include T. pallidum endemicum which causes Bejel, T. pallidum pertenue causes Yaws, and T. pallidum carateum causes Pinta. Phenotypically these four diseases appear similar along with their serology, but are very distinct based on their unique genotypes. T. pallidum genome is circular and is also very small in comparison to other prokaryotes as it contains roughly 1000 kilobase pairs in its genome. These distinct diseases are only found in humans. T. pallidum is classified as a spirochete, and its shape resembles that of a home telephone cord spiraling. Its structure is very thin and flexible. T. pallidum is considered a Gram-negative bacterium. Around its spiral shaped body, there is a cytoplasmic membrane which is enclosed by a second outer membrane. In between the cytoplasmic and outer membrane, there is a thin layer of peptidoglycan for stability. T. pallidum is a motile bacterium that possess endoflagella located in the periplasmic space between the two membranes, allowing the microbe to maneuver its environment, in what has been documented as in a corkscrew fashion. T. pallidum relies on chemotactic responses to be motile. The flagella contain 36 gene encoding proteins responsible for the structure and function of the flagella, along with two copies of the flagellar switch protein FliG. T. pallidum length ranges from 6-15µm in length and is 0.2 µm in width. T. pallidum is a small bacterium that requires a dark field microscopy to be visualized. Other techniques involved for visualizing this microbe include using a modified Steiner silver, the Dieterle stain or the Giemsa stain. This microbe is an obligate parasite as it needs a host to conduct its metabolic processes and life cycle; it is difficult to culture T. pallidum under in vitro conditions. T. pallidum thrives under low oxygen conditions from 10-20% levels, making it microaerophilic. It is also temperature dependent, as it prefers temperatures relative to the human body. T.pallidum is a primary pathogen because of its ability to compromise host’s immune system. As far as metabolic pathways are concerned, it does not contain a pathway to synthesize nucleotides, fatty acids, enzyme cofactors and most amino acids as well as lack genes to metabolize amino acids or fatty acids as a possible energy source. However, it does contain the necessities essential for glycolysis, but lacks genes responsible for steps that take place after glycolysis. T. pallidum lacks genes that would allow products from glycolysis to enter the TCA cycle, and eventually the electron transport chain. Lastly, it lacks genes that allows oxidative phosphorylation pathways to occur. Due to T. pallidum missing integral components for the TCA cycle and the ETC, its one dimensionality based solely on glucose metabolism via glycolysis, it cannot optimize its energy production. T. pallidum also has a specific set of genes that code for 18 unique ATP-binding cassette transporters with specificity for certain molecules. The limited pathway ability of T. pallidum can be attributed to the small genome it possess. It is heavily reliant upon the conditions the host supplies it with. These factors make it difficult for scientist to readily culture T. pallidum because of the ideal conditions it requires and the limited pathways it has.

Every point of information REQUIRES CITATION using the citation tool shown above.

History and Discovery

Include some current research, with at least one figure showing data.

Sometime during the 15th century, Europe recognized syphilis as a new disease. There are two main theories that have arisen. The first of the theories is, it is believed that during the time Christopher Columbus and his crew of ships went on their voyage to the New World, they may have contracted the disease and brought it back to Europe. The second theory is, syphilis was present in Europe but went undiagnosed. John Hunter, was a prominent physician and venereologist during the 18th century in Scotland. Hunter went on to conduct his own investigation of two rampant diseases. He set out to see if syphilis, and gonorrhea were similar diseases or if they differed. Just like many famous people who worked within these fields, he intentionally inoculated himself with some pus like fluid from an individual who had a disease. Unknown to Hunter, he inoculated himself with two etiological agents for both gonorrhea and syphilis. His findings would alter the scientific community for years, complicating any knowledge the scientific community already had. Eventually, Philippe Ricord developed his own study on the diseases. In 1838, Philippe Ricord published his astute findings. He identified syphilis and gonorrhea as two distinct diseases.

In February of 1905, Franz Eilhard Schulze and his assistant John Siegel believed they had come across the etiological agent responsible for syphilis. However, they speculated the etiological agent they discovered was possibly responsible for other prevalent diseases. It was first classified as a protozoan with the scientific name Cytorrhyctes luis. To conclusively dismiss any doubts, the director of the Berlin Imperial Health Service, proposed that Edmond Lesser delve deeper into this theory for a definitive answer. Lesser and colleagues placed Paul Erich Hoffmann an assistant dermatologist, Fritz Schaudinn, and Fred Neufeld an expert in bacteriology in charge of the assignment. Fritz Richard Schauddin attended the Wilhelm University, where he studied zoology. In March of 1905, Schaudinn looked at a papula from a woman’s vulva with secondary syphilis. Under a Zeiss microscope, Schaudinn observed the mannerisms and shape of the T. pallidum. He described the microorganisms as very light, thin, and their motility as back and forth. Based on these characteristics displayed, the trio named it Spirochaeta pallida. More research revealed to the trio, that the microbe resided in multiple samples of syphilis ulcers. Neufeld left the group during the time the group thought about publication of their findings. Schauddin and Hoffmann published a provisional work of their studies of in April. In May the duo presented their research to the Berlin Medical society. Their work was repeatedly challenged and many people at the conference fervently believed that Cytorrhyctes luis, was the etiological agent responsible for syphilis. The conference was ended by the President of the Berlin Medical society stating, a new etiological agent needs to be found for syphilis. Albert Neisser was a well-known venereologist, and very opposed to the findings of Schauddin and Hoffmann. Neisser conducted similar research and realized that the findings of the duo were conclusive and mirrored his results. Future studies showed numerous discoveries of syphilis observed in monkeys inoculated with the bacteria and even in children with congenital syphilis solidifying the Schauddin and Hoffmann’s findings. Schauddin and Hoffman decided to change the name the scientific name to Treponema pallidum. The medical world eventually, and unanimously concluded that T. pallidum was the etiological agent responsible for syphilis. Schauddin, who was credited by Hoffmann for discovering the etiological agent for syphilis, suffered from gastrointestinal amebian abscesses. This circumstance forced him to have an immediate surgery. Complications from the infection and surgery led to his early death on June 22nd, 1906.

In the year 1932, the United States Public Health Service began what was known as the “Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male” experiment down in rural Tuskegee, Alabama. Their patients came from Macon County, Alabama. The United States Public Health service, was interested in studying the history of syphilis. In the study, there were a total of 600 test subjects. Researchers conducting the study told their patients they were going to be treated for “bad blood”. The term bad blood refers to number of health related issues including anemia, fatigue. The study was done without the patient’s informed consent for the treatment. Out of the 600 patients, 399 already had syphilis, and the remaining 201 were syphilis free. The test subjects were told, in return for their participation in the research, they would receive free health-care from the United States government which also included meals and burial insurance. The research was supposed to last for a period of six months, but continued on for an astonishing forty years. They were promised treatment for bad blood but unfortunately the researchers did not live up to their promise. July 25th, 1972, a writer for the associated press, Jean Heller released the story that the United States Public Health Service’s research had some questionable ethics involved. In the year 1947 penicillin was found to help treat the disease, and during the time of the study no actions were taken to provide the patients with treatment. The Assistant Secretary for Health and Scientific Affairs Merlin K. Duval appointed an advisory panel to further review the ethics of the study. The advisory panel consisted of nine individuals with backgrounds in law, medicine, and religion. The advisory panel found that the patients did agree to agree to be screened and treated. On the other hand, it was concluded the researchers never told the patients what the real intent of the study was or any of the possible consequences associated with the study. The patients were never notified by the researchers that there was a chance for mortality. The information the patients received was concluded to be misleading and inconclusive for the patients to give informed consent. Even with the latest treatment of penicillin, there was no evidence that researchers either suggested the option of penicillin to patients or the option to discontinue the study. The study was immediately stopped in October of 1972, cited as being unethical and in-humane. In the following year a class-action lawsuit was filed for the patients still alive and the families of the deceased. Then in 1974, a settlement of 10 million dollars was reached for those effected. The United States government once again promised lifetime health benefits to those who were still living with the disease as well as burial service. In 1975 it was expanded to cover loved ones of the effected in the study. The last study patient under the Tuskegee experiments died in 2004.

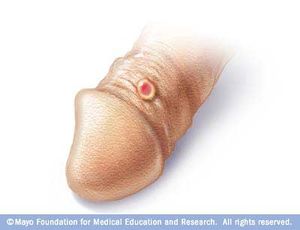

Transmission and Symptoms

Include some current research, with at least one figure showing data.

Section 4

Conclusion

References

Authored for BIOL 238 Microbiology, taught by Joan Slonczewski, 2016, Kenyon College.