Hookworm

Etiology/Bacteriology

Taxonomy

| Domain = Eukaryota | Phylum = Nematoda | Class = Secernentea | Order = Strongylida | Family = Ancylostomatidae | Genus = Necator/ Ancylostoma | species = [[ N. americanus/ A. duodenale]] [1,2].

Description

The hookworm is a soil-transmitted helminth that is common in many third world and developing countries[3]. There are several types of hookworms that infect dogs, cats and other mammals. However, there are only two species that typically infect human beings— N. americanus and A. duodenale[4]. Hookworms are located in areas with warm, moist climates. Most people with hookworm infections have no symptoms. In some cases, the worms' voracious appetite for blood can lead to anemia and protein loss[3]. The loss of vital nutrients for a third world inhabitant reduces the ability to fight future infections. While mortality from hookworm is low-- hookworm-related deaths are under-recognized. Additionally, severe anemia

Pathogenesis

Transmission

An infected human being will have eggs in their stool. Under favorable conditions, 20-30°C, the larvae will hatch and mature in 5 to 10 days. If another human walks barefoot on the soil where the larvae reside, they can become infected [4]. After 5 or more minutes of skin contact the larvae will penetrate the skin [3]. After entering the skin larvae penetrate the blood vessels and are carried to the lungs where they penetrate into the pulmonary alveoli. Afterwards, they ascend the bronchial tree and are then swallowed and attach to the small intestine. During this time, the hookworms excrete chemicals that allow them to travel throughout the body—as well as avoid the immune response. N. americanus can only infect by penetration of the host skin. Unlike N. americanus, A. duodenale can be ingested and still infect the host.

Virulence Factor

Epidemiology

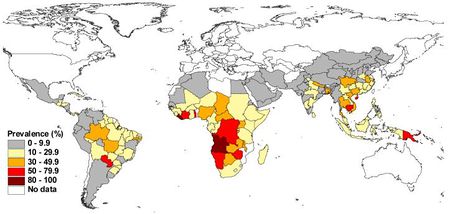

Around 500-750 million people in the world are infected with hookworm [4]. Third world countries' higher rates of poor sanitation and lack of access to clean water facilitates the prevalence of hookworm infection.In certain areas prevalence of hookworm infection can be 90%[3]. Agricultural laborers are at a high risk for hookworm—especially in areas where human feces is in fertilizer.

Clinical Features

Diagnosis

Treatment

Mortality is extremely low with hookworm infection. For classic hookworm disease appropriate treatment is anthelmintic drugs [3]. Treatments that may be used are—Albendazole single 400-mg does for 3 days, Mebendazole 100 mg twice daily for 3 days, pyrantel pamoate in several 11 mg/kg doses over 3 days.

Prevention

The best way to avoid hookworm infection is to avoid walking barefoot in areas where hookworm infection is common. The avoidance of walking on human fecal material and improving the sewage disposal systems can reduce the risks of hookworm infection.

Host Immune response

The larval sheath antigens are immunogenic. Most larvae cast off their outer sheath upon penetration. Potentially, diverting the immune response away from the larvae [6]. In a study with infected individuals all five human immunoglobuilin isotypes were found in response to larvae and adult hookworm antigens. However, the responses varied in larval antigens. Detection of IgE antibodies against ‘’necator’’ proved to be a highly specific test for diagnosing hookworm infection [6].

References

1. N americanus genome. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/?term=N+americanus

2. NCBI. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Taxonomy/Browser/wwwtax.cgi?name=Necator+americanus

3. Medscape. Hookworm. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/218805-overview#aw2aab6b2b6

4. CDC. Hookworm. http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/Hookworm/

5. Eradicating Hookworm. http://www.rockefeller100.org/exhibits/show/health/eradicating-hookworm

6. Immune response in Hookworm Infections. Alex Loukas and Paul Prociv. Clinical Microbiology reviews. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC89000/

7. Human Hookworm Infection in the 21st century. Brooker, Simon. Jeeffrey Bethony and Peter J. Hotez. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2268732/#R79

8. Soil-transmitted helminth infections: updating the global picture. de Silva, Nilathi R, Simon Brooker, Peter J Hotez, Antonio Monstresor, Dirk Engels, Lorenzo Savioli. http://www.sciencedirect.com.ezproxy.lib.ou.edu/science/article/pii/S1471492203002757