Pasteurella

A Microbial Biorealm page on the genus Pasteurella

Classification

Higher order taxa:

Bacteria; Proteobacteria; Gammaproteobacteria; Pasteurellales; Pasteurellaceae

Species:

Pasteurella aerogenes; P. avium; P. bettyae; P. caballi; P. canis; P. dagmatis; P. gallinarum; P. langaaensis; P. mairii; P. multocida; P. pneumotropica; P. skyensis; P. stomatis; P. testudinis; P. trehalosi; P. volantium; P. sp.

Description and Significance

Pasteurella pneumotropica is an opportunistic pathogen that can be often found in many commerical and research colonies of rodents.

Genome Structure

The genome of Pasteurella has a GC content of 37.7-45.9 mol % and the genome molecular weights are 1.4-2.1 * 109 Da. An avian strain of P. multocida that was isolated from a fowl cholera-infected chicken was found to be 2,257,487 bp long (1.5* 109 Da) with 2,014 predicted coding regions. P. multocida was studying using microarray analysis in relation to nutrient limitation: about 1/3 of the presumed genes changed expression level when the the nutrients allowed were changed. Genes involved in energy metabolism, protein-, nucleotide- and lipid synthesis, iron transport and cellular binding were upregulated in rich media. Genes dealing with amino acid biosynthesis, protein transport, OMP and heat shock proteins were upregulated in nutrient-deficient media (Prokaryotes).

Cell Structure and Metabolism

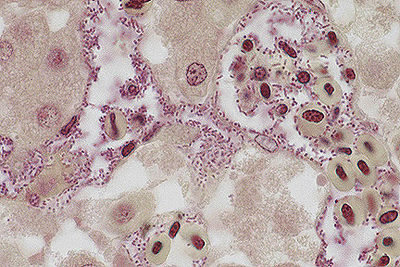

Pasteurella pneumotropica is a short, gram negative rod or coccobacillus with a size of 0.5 by 1.2 micrometers on average. It produces acid but not gas through using dextrose, glycerol, inositol, lactose, maltose, and mannose. It is oxidase- and catalase-positive and is able to reduce nitrate to nitrite (Charles River Lab). Pasteurella are also non-motile and often produce bipolar staining patterns. It is suggested that the strongly hydrophilic capsule found on P. multocida aides in the protecting the bacteria against dehydration and improves transmission from host to host and survival in the environment. In addition, it as been observed that encapsulated strains are more resistant to phagocytosis than those without a capsule; they are also much more virulent in mice than their nonencapsulated relatives (Prokaryotes).

Ecology

Pasteurella bacteria are part of the natural oral, respiratory, genital, and gastrointestinal floras of various wild and domestic animals; for example, P. multocida ssp. gallicida is most frequently isolated from birds and occasionally from pigs, and P. multocida subsp. septica is isolated from cats more than from dogs and infrequently from humans. Some of these bacteria are also considered pathogenic to animals and even humans. Interactions among Pasteurella and members of the flora of the different mucosal membranes where they can be found naturally as well as interactions between Pasteurella and its host are not known (Prokaryotes). When grown on blood agar, P. pneumotropica forms within 24 hours light gray to yellow-colored colonies about 0.5 times 1.2 micrometers in size (Charles River Lab).

Pathology

Pasteurella pneumotropica is an opportunistic pathogen that is not often associated with clinical diseases. However, when infecting a host, it can generally be recovered from the respiratory tract, the urogenital tract, or conjunctiva from the host: common hosts include mice, rats, hamsters, guinea pigs, rabbits, cats, and other laboratory animals. In the case of humans, many strains from Pasteurella multocida subsp. multocida, Pasteurella multocida subsp. septica, Pasteurella canis, Pasteurella stomatis, and Pasteurella dogmatis have been isolated from infected humans. Toxins were produced only by one strain of P. multocida subsp. multocida and P. canis; in addition, other than one severe case of necrotizing cellulitits caused by P. dagmatis, P. multocida subsp. multocida or P. multocida subsp. septica was involved in the more serious cases of infection. Symptoms of a Pasteurella infection vary on which body organ is involved and how long the disease is present. One of the most common symptoms is during respiratory infection and manifests as a nasal discharge. Others include sneezing, congestion, conjunctivitis, and clogged tear ducts. Pasteurella infections also can cause abscesses under the skin that can be chronic, requiring surgery to correct. Some abscesses can go as far as causing central nervous symptoms like oscillations of the eyes [nystagmus], circling to one side, and severe tilting of the head ([wry neck or torticollis] (Long Beach Animal Hospital).

References

General:

- Charles River Laboratories: "A review of Pasteurella pneumotropica."

- Christensen, Henrik and Magne Bisgaard. "The Genus Pasteurella." Release 3.14. The Prokaryotes: An Evolving Electronic Resource for the Microbiological Community

Pathology:

- Long Beach Animal Hospital: Pasteurellosis.