Lemierre's Syndrome

By Jessie Griffith

Summary of this Article

This article will focus on Lemierre’s Syndrome. This disease has implications for human health, because although it is rare, the disease progresses toward extremely dangerous symptomology that can result in sepsis of the blood and eventually death. The research question that I will be addressing in this paper is how Fusobacterium necrophorum plays a role in Lemierre’s syndrome, and what other conditions can result from this bacterial infection. In this article I hope to demonstrate how an exogenously acquired human pathogen, Fusobacterium necrophorum can cause Lemierre’s Syndrome, and what processes lead toward the various conditions that can stem from this infection. WARNING: the following article may contain images unsuitable for those who are faint of heart, as photographs of the infection will be shown.

Defining Lemierre’s Syndrome

Lemierre’s Syndrome is a post-anginal septicemic infection.[1] A post-angial infection is one in which the first symptoms include pharyngitis, and later symptoms include a high fever, cervical adenopathy, thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein, and distant abscess formation [2]. In lay terms, cervical adenopathy is enlargement of lymph nodes specifically within the neck; thrombophlebitis refers to inflammation of a vein associated with thrombosis, in this case, specifically the jugular vein becomes inflamed. A septicemic infection is one in which the infection or its byproducts enter the bloodstream and cause inflammation throughout the body. Lemierre’s Syndrome is treatable with antibiotics, and some researchers have found that metronidazole is a particularly effective antibiotic for clearing out the infection due to its having a ß-lactamase inhibitor, compared to penicillin, which would need to be paired with another drug to increase its efficacy [3].

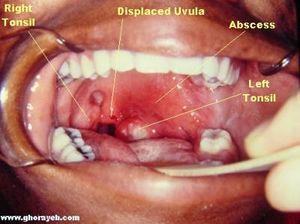

Three terms that will be used in the course of this article are Lemierre’s Syndrome, postanginal sepsis, and necrobacillosis. The three denote relatively the same condition; however there are slight differences between what they can mean when used precisely. Postanginal sepsis refers to the clinical term to describe the condition of complications that arise from peritonsillar abscesses, meaning an infected disease pocket that occurs in the throat near the tonsils (Fig. 1). These abscesses do not need to be caused by an anaerobe such as Fusobacterium necrophorum, but the location and severity of the abscess does need to fit specifically with the definition of postanginal sepsis. Alternatively, the term postanginal sepsis can also refer to the complications that arise from purulent pharyngitis. This term does not denote the presence or lack thereof of Fusobacterium necrophorum. Necrobacillosis, however, does denote the presence of Fusobacterium necrophorum. Necrobacillosis is a blanket term, and can be use to describe infection of Fusobacterium necrophorum in animals or humans. When designating specifically the host, a term such as human necrobacillosis must be used. When an infection of this bacteria leads to peritonsillar abscesses, thrombophlebitis, and septicemia, that is when a clinician would term the disease Lemierre’s Syndrome.[4]

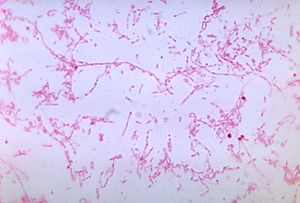

For unknown reasons, Lemierre’s syndrome is a disease that affects young adult males more than any other demographic [5]. This incidence in young males over females is very slight, and the small number of samples of this condition make it hard to know for sure whether this is a real demographic difference. It is known that infection of Fusobacterium necrophorum is typically exogenous, but it remains unknown whether transmission between human or from animals plays a role in sourcing the infection. Fusobacterium species are present in the human body at a very low concentration in healthy individuals. The oral cavity, gastrointestinal tract, and female genital tract are all locations from which Fusobacterium has been identified in healthy individuals.[6] However, the disease is undeniably rare; some studies rate the prevalence of this condition as low as one in a million.[7] The disease is typically caused by a gram-negative, anaerobic, bacilli called Fusobacterium necrophorum, although the presence of this bacteria is not requisite for a patient’s condition to be deemed Lemierre’s syndrome (Fig. 2).[8]

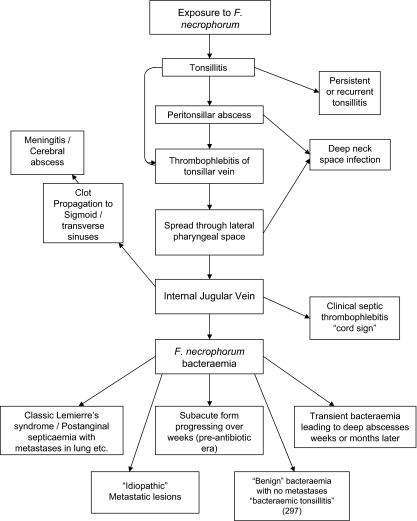

As stated before, the presence of Fusobacterium necrophorum is not requisite for a condition to be termed Lemierre’s Syndrome, therefore, there has been much controversy over the characteristics of a patient's condition that qualify them to fall under this classification. Similarly, exposure to the exogenous Fusobacterium necrophorum, which is also a part of normal throat flora does not always result in Lemierre’s syndrome; it can also result in tonsillitis, meningitis, and metastatic lesions, and a whole host of other issues (Fig. 3)[9]. It is currently not known why infection of Fusobacterium necrophorum only occasionally causes Lemierre’s Syndrome, and why it takes divergent pathways to different conditions instead of progressing in a linear manner from one symptom to another. For more information on these other complications of Fusobacterium necrophorum infection, visit the section of this page titled: Complications Associated with Lemierre’s Syndrome.

Lemierre’s syndrome is classically associated with the post-anginal sepsis with later metastases of the infection into the lungs. It is classified as a severe septicemic infection, and is also known as necrobacillosis [10]. It is classified as a septicemic infection due to the fact that it can be cultured from the blood; the infection will not remain in the lesions where it develops. The thrombophlebitis that is associated with this condition is also an extremely important factor in the classification of these symptoms of Lemierre’s syndrome. Most patients of Lemierre syndrome typically show symptoms of a high fever, neck pain, and pulmonary problems, the thrombosis of the jugular is depicted in figure 4.[11] Some define Lemierre’s Syndrome as a complication arising from an oropharyngeal infection due to the accumulation and infection of Fusobacterium necrophorum within the infected tissue.

History of Lemierre’s Syndrome

To better understand Lemierre’s Syndrome, it is important to briefly explore the history of the disease and to note prominent figures in the research of Lemierre’s Syndrome over time. The first person to recognize that Fusobacterium necrophorum was causing a disease was Loeffler, who recognized it as the cause for calf diphtheria. After culturing the bacteria, determining its gram stain and morphology, Flugge gave the bacteria the name Bacillus necrophorum. Bang was the first one to isolate the bacteria from cholera in swines, and he termed the abscess formed in the liver, necrobacillosis, a name which many people consider to be equivalent to post-anginal sepsis and the similarly resulting Lemierre’s Syndrome.

André Lemierre, for whom the condition is named, is the most prominent figure in the history of research on post-anginal septicemic infections. André Lemierre resided and worked in Paris France as a microbiologist and physician during his life from 1875 to 1956. Although he did not discover the bacterium at the root cause of this condition, this credit is often attributed to Loeffler, and he was also not the first person to describe the symptoms associated with post-anginal sepsis, which is credited to Bang when he termed it necrobacillosis, he did play a major role in clarifying how to classify the condition through his extensive description of the course the disease progresses through over time and the symptoms that patients typically exhibit. In a 1939 clinical review of the disease he described that “The appearance and repetition several days after the onset of a sore throat (and particularly of a tonsillar abscess) of severe pyrexial attacks with an initial rigor or still more certainly the occurrence of pulmonary infarcts and arthritic manifestations, constitute a syndrome so characteristic that [mistaking it] is almost impossible”.

Although Lemierre said that mistaking this condition for another is nearly impossible, it actually occurs consistently throughout case studies on this disease. Often times, because sore throat is one of the most common reasons for a doctor’s visit, symptoms can initially be written off as something less medically important than they actually are. Lemierre’s Syndrome is often referred to as “The Forgotten Disease” because after the advent of antibiotics, infections of this type and severity became less common.[12] When this case does present itself, however, actual definitive identifications of the disease are few and far between because the syndrome itself requires positive identification of Fusobacterium necrophorum for the proper classification as Lemierre’s syndrome. To identify the disease as such, blood cultures must be done, and the anaerobic bacteria must be grown in order to ascertain whether or not the patient is truly infected with Fusobacterium necrophorum in which case the patient can be classified as having Lemierre’s Syndrome.[13]

The Relationship Fusobacterium necrophorum with Lemierre’ s Syndrome

Around seventy percent of the case studies reported on in the literature since 1970 that fulfilled the criteria for Lemierre’s Syndrome are associated with a positive culture report for Fusobacterium necrophorum ([14], Figure 5). If Fusobacterium necrophorum is not requisite for contracting Lemierre’s Syndrome, then what is the relationship between Human necrobacillosis (infection by Fusobacterium necrophorum) and Lemierre’s Syndrome?

Research suggests that Fusobacterium necrophorum, along with other members of the Fusobacterium genera, such as Fusobacterium nucleatum and Fusobacterium mortiferum, is often present in the mucosa of the throat of healthy individuals who are not fighting off infection of any kind. This would suggest, contrary to previous thought, that infection by Fusobacterium necrophorum is not always exogenously acquired. However, the research also suggests that an exogenously acquired viral or other polymicrobial infection makes conditio that facilitate Fusobacterium necrophorum's ability to migrate into the mucosa and begin forming an infection, and then move over to the close-by internal jugular veins where it begins to cause thrombophlebitis.[15]

In the cases of Lemierre’s Syndrome in which infection has occurred due to another species outside of a member of the Fusobacterium genera, which is actually fairly uncommon, some sources reporting that this only occurs in as little as 10% of cases, many sources cite it as an atypical presentation of Lemierre’s Syndrome. [16] In the ten percent of cases in which Fusobacterium necrophorum is not present, infection usually stems from both the Bacteroides and Eikenella genera, both of which are included in typical oral flora. Additionally, Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes have also been shown to be present when cultures are taken from patients with Lemierre’s Syndrome.[17] Infections in which Fusobacterium necrophorum are not present are grouped as outliers in other studies, much in the same way that cases in which thrombosis of the internal jugular vein is not presented are excluded.

Although a positive culture result for Fusobacterium necrophorum is not required for a condition to be deemed Lemierre’s Syndrome, infection by Fusobacterium necrophorum and Lemierre’s syndrome seem to be inexplicably intertwined. Then, it is important to understand the mechanism for pathogenesis of Fusobacterium necrophorum. Fusobacterium necrophorum is able to infect a variety of animals, including humans of course; among the animals that it can infect is cattle, which is a major cause of concern for the bovine industries. [18]The way that Fusobacterium necrophorum infects its host is not well understood. Some have suggested that it uses a variety of virulence factors, which may include leukotoxin, endotoxin, hemolysin, hemagglutinin, proteases, and adhesin, leukotoxin being the most important for infection in ruminant species.[19] Interestingly, Fusobacterium necrophorum has split into a few subspecies, and the ones that infect humans appear to be different from the ones that infect animals, which would suggest that transmission between animals is unlikely due to the fact that the strains differ biologically and biochemically.[20]

Human pathogenesis is attributed greatly to the subspecies of Fusobacterium necrophorum funduliforme. Studies have shown that this is likely the subspecies that infects human through identification in blood cultures in addition to inoculation into animals hosts such as mice; these tests revealed a decreased ability to impact the host, and that time mouse immune system was able to clear the infection much better than when inoculated with other subspecies of Fusobacterium necrophorum.[21] It is maintained that Leukotoxin, along with coagulatory elements, are causative in allowing the Fusobacterium necrophorum to infiltrate the walls of the oropharynx tract and seed an infection anaerobically.[22] Once this infection makes the jump from the oropharynx tract into the internal jugular vein, thrombophlebitis and anginal septicemia follow, which created the conditions requisite for Lemierre’s Syndrome to be diagnosed in a patient.

Complications Associated with Lemierre’s Syndrome

Lemierre’s Syndrome can cause a wide array of complications that are potentially very dangerous. In a case study concerning two children that both had Lemierre’s Syndrome, doctors found that the condition caused the children to develop neurological complications.[23] One of the children developed what is called Clival Syndrome. This serious complication results from leptomeningitis of the clivus; it can cause nerve palsies (Peer 2010) The other child of the report also developed a palsy as a result of clival osteomyelitis (Peer 2010).

Fusobacterium necrophorum infection can also play a role in chronic sinus infections or sinusitis. In a few reported cases, sinus infections have lead to the infection moving towards the brain, and meningitis has developed [24]. Interestingly, although it is more commonly reported that Fusobacterium necrophorum infection leads to meningitis, it has not been shown at this time that Lemierre’s Syndrome caused by Fusobacterium necrophorum has ever caused meningitis [25]. Meningitis is also very rarely caused by anaerobic bacteria, which is another facet of Fusobacterium necrophorum's dangerousness that is occasionally overlooked.

Septic emboli from the infection can also spread into lung tissue and form serious respiratory complications. Two potential pulmonary problems that can arise as serious complications from Lemierre’s Syndrome is pleurisy and empyema [26]. Pleurisy is an accumulation of fluids in the pleural layers of the lungs that cause irritation, and chest pain for someone experiencing it.[27] The chest pain associated with pleurisy worsens when the person takes a breath in, typically. Empyema, on the other hand, is an accumulation of pus in the pleural space between the lung and the wall of the chest cavity.[28] Empyema puts pressure on the lung that can make it hard to breath. Occasionally, surgery to help a patient breathe better may need to be conducted. Otherwise, antibiotics and pus drainage are the primary means of dealing with empyema.[29]

Due to the septicemic nature of human necrobacillosis, before times in which antibiotics were prevalent, or without treatment, this condition can quickly become fatal. In Lemierre’s initial report on the condition, he found that there was about a 80% death rate amongst the patients he saw, most of which, we can assume were not treated with antibiotics effectively.[30] This is truly a dangerous disease and condition, and appropriate measures should be taken to make sure that it is given the attention that it so deserves.

Treatment for Lemierre’s Syndrome

It is very important to begin an antibiotic course of therapy as soon as possible when a patient exhibits the symptoms of Lemierre’s Syndrome. The high fever associated with the infection is also something that must be treated with swiftness. Typically, use of antibiotics will help in staving off the fever, but in occasional cases, it does not seem to help. The use of many different antibiotics have been shown to be one hundred percent effective against all strains. These antibiotics that Fusobacterium necrophorum is particularly sensitive to include metronidazole, ticarcillin-clavulanate, cefoxitin, co-amoxiclav, and imipenem; however most typically used in vivo are metronidazole, and penicillin in conjunction with another antibiotic [31]. It is often advised that the antibiotic that is used be a ß-Lactamase inhibitor, because this has been shown to be particularly effective in stopping an infection by Fusobacterium necrophorum[32]. In contrast to all of these antibiotics that are very effective against Fusobacterium necrophorum, about twenty two percent of Fusobacterium necrophorum strains are resistant to erythromycin.[33] This incidence of resistance is very high, and can possibly be attributed to increased use of antibiotics in the modern era. Additionally, when antibiotics are administered to a patient, it is preferred that they be administered intravenously rather than orally. This route of administration increases their efficacy.[34]

Because of the inflammation of the major veins and arteries associated with human necrobacillosis and Lemierre’s Syndrome, anticoagulants are also occasionally prescribed to assist in healing. However, the research on anticoagulant therapy is inconclusive to this day, as no controlled study has actually been able to successfully prove or disprove their efficacy [35]. Anticoagulants have been used in some patient cases, and case studies written on these patients mention the drugs used to potentially assist in the treatment process. One case study prescribed low molecular weight heparin for their patient, and then continued the course of treatment with twelve weeks of warfarin to follow up after she had left the hospital.[36] There are many concerns surrounding anticoagulant therapy, unfortunately. Anticoagulant therapy has the potential to cause life threatening problems if something were to go wrong. For instance, one of the inherent risks of anticoagulant therapy is that potential for the septic emboli to metastasize and spread to other parts of the body to cause even more damage to internal organs.[37]

The risk for metastatic infection is inherent in human necrobacillosis, however. Another case study on two patients with metastatic infections resulting from septic emboli shows that without the use of anticoagulant therapy, the infection metastasized and was able to cause septic arthritis in the shoulder and hip joints of one patient, and it was also able to cause encephalopathy.[38]

Conclusion

In conclusion, this article set out to explain how Fusobacterium necrophorum is related to Lemierre’s Syndrome, and it also set out describe the condition in greater detail as well as the conditions that can stem from Lemierre’s Syndrome. Lemierre’s Syndrome can be a life threatening condition, that must be paid close attention to and monitored by a healthcare professional. Although rare, around an incidence of one in a million in current times, there is potential for this infection to be on the rise, and we should be vigilant in order to protect ourselves from it. It must be treated with antibiotics as soon as identified, and one must go to their healthcare provider if they suspect that their persistent sore throat is causing other symptoms related to this condition.

References

- ↑ Riordan T.. Human infection with Fusobacterium necrophorum (Necrobacillosis), with a focus on Lemierre’s syndrome. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20(4):622-59.

- ↑ C. M., Clover R. Lemierre syndrome: postanginal sepsis. Journal of the American Board of Family Practice. 1995;8(5):384–391.

- ↑ Riordan T.. Human infection with Fusobacterium necrophorum (Necrobacillosis), with a focus on Lemierre’s syndrome. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20(4):622-59.

- ↑ Elzubeir A, Elzubeir S, Szuszman A, Petkova D, Fletcher T (2015) Lemierre’s Syndrome: The Forgotten Disease?. Clin Microbiol 4: 180.

- ↑ Riordan T.. Human infection with Fusobacterium necrophorum (Necrobacillosis), with a focus on Lemierre’s syndrome. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20(4):622-59.

- ↑ [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8711893/ Tan, Z.L., Nagaraja, T.G. and Chengappa, M.M., 1996. Fusobacterium necrophorum: Virulence factors, pathogenic mechanism and control measures. Veterinary Research Communications, 20 (2), 113-140 ]

- ↑ Hagelskjaer, L. H., J. Prag, J. Malczynski, and J. H. Kristensen. 1998. Incidence and clinical epidemiology of necrobacillosis, including Lemierre’s syndrome, in Denmark 1990–1995. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 17:561–565

- ↑ Courmont, P., and A. Cade. 1900. Sur une septico-pyohe´mie de l’homme simulant la peste et cause´e par un strepto-bacille anae´robie. Arch. de Me´d. Exp. 12:393–418.

- ↑ Riordan T.. Human infection with Fusobacterium necrophorum (Necrobacillosis), with a focus on Lemierre’s syndrome. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20(4):622-59.

- ↑ [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC440844/ Dack, G. M. "Non-sporeforming Anaerobic Bacteria of Medical Importance."Bacteriol. Rev. 4.4 (1940): 227-59.]

- ↑ Lu, Miranda, Zumin Vasavada, and Christina Tanner. "Lemierre Syndrome Following Oropharyngeal Infection: A Case Series." J Am Board Fam Med 22.1 (2009): 79-83. Print.

- ↑ Elzubeir A, Elzubeir S, Szuszman A, Petkova D, Fletcher T (2015) Lemierre’s Syndrome: The Forgotten Disease?. Clin Microbiol 4: 180.

- ↑ Elzubeir A, Elzubeir S, Szuszman A, Petkova D, Fletcher T (2015) Lemierre’s Syndrome: The Forgotten Disease?. Clin Microbiol 4: 180.

- ↑ Riordan T.. Human infection with Fusobacterium necrophorum (Necrobacillosis), with a focus on Lemierre’s syndrome. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20(4):622-59.

- ↑ James A. Coultas, Neena Bodasing, Paul Horrocks, and Anthony Cadwgan, “Lemierre’s Syndrome: Recognising a Typical Presentation of a Rare Condition,” Case Reports in Infectious Diseases, vol. 2015, Article ID 797415, 5 pages, 2015.

- ↑ Dees, Paola, and David Berman. "Lemierre Syndrome." Infectious Disease and Antimicrobial Agents. E-Sun Technologies Inc., n.d. Web. 24 Apr. 2016.

- ↑ Dees, Paola, and David Berman. "Lemierre Syndrome." Infectious Disease and Antimicrobial Agents. E-Sun Technologies Inc., n.d. Web. 24 Apr. 2016.

- ↑ [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16701574/ Nagaraja TG, Narayanan SK, Stewart GC, Chengappa MM. Fusobacterium necrophorum infections in animals: pathogenesis and pathogenic mechanisms. Anaerobe. 2005;11:239–246.]

- ↑ [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16701574/ Nagaraja TG, Narayanan SK, Stewart GC, Chengappa MM. Fusobacterium necrophorum infections in animals: pathogenesis and pathogenic mechanisms. Anaerobe. 2005;11:239–246.]

- ↑ [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16701574/ Nagaraja TG, Narayanan SK, Stewart GC, Chengappa MM. Fusobacterium necrophorum infections in animals: pathogenesis and pathogenic mechanisms. Anaerobe. 2005;11:239–246.]

- ↑ [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8711893/ Tan, Z.L., Nagaraja, T.G. and Chengappa, M.M., 1996. Fusobacterium necrophorum: Virulence factors, pathogenic mechanism and control measures. Veterinary Research Communications, 20 (2), 113-140 ]

- ↑ [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8711893/ Tan, Z.L., Nagaraja, T.G. and Chengappa, M.M., 1996. Fusobacterium necrophorum: Virulence factors, pathogenic mechanism and control measures. Veterinary Research Communications, 20 (2), 113-140 ]

- ↑ [http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1469-8749.2010.03718.x/abstract/ Peer Mohamed B., Carr L. Neurological complications in two children with Lemierre syndrome.Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. 2010;52(8):779–781. ]

- ↑ Riordan T.. Human infection with Fusobacterium necrophorum (Necrobacillosis), with a focus on Lemierre’s syndrome. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20(4):622-59.

- ↑ Riordan T.. Human infection with Fusobacterium necrophorum (Necrobacillosis), with a focus on Lemierre’s syndrome. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20(4):622-59.

- ↑ Riordan T.. Human infection with Fusobacterium necrophorum (Necrobacillosis), with a focus on Lemierre’s syndrome. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20(4):622-59.

- ↑ [http://www.medicinenet.com/pleurisy/article.htm/ Schiffman, George. "Pleurisy: Symptoms, Treatment, Pain & Causes."MedicineNet. N.p., 3 Aug. 2015. Web. 24 Apr. 2016.]

- ↑ Jatin. "Empyema: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia." U.S National Library of Medicine. U.S. National Library of Medicine, 2 Apr. 2015. Web. 24 Apr. 2016.

- ↑ Jatin. "Empyema: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia." U.S National Library of Medicine. U.S. National Library of Medicine, 2 Apr. 2015. Web. 24 Apr. 2016.

- ↑ [Lemierre, A. 1936. On certain septicaemias due to anaerobic organisms. Lancet ii:701-703.]

- ↑ Riordan T.. Human infection with Fusobacterium necrophorum (Necrobacillosis), with a focus on Lemierre’s syndrome. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20(4):622-59.

- ↑ Riordan T.. Human infection with Fusobacterium necrophorum (Necrobacillosis), with a focus on Lemierre’s syndrome. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20(4):622-59.

- ↑ Goldhagen, J., B. A. Alford, L. H. Prewitt, L. Thompson, and M. K. Hostetter. 1988. Suppurative thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein: report of three cases and review of the pediatric literature.Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 7:410-414.

- ↑ James A. Coultas, Neena Bodasing, Paul Horrocks, and Anthony Cadwgan, “Lemierre’s Syndrome: Recognising a Typical Presentation of a Rare Condition,” Case Reports in Infectious Diseases, vol. 2015, Article ID 797415, 5 pages, 2015.

- ↑ Riordan T.. Human infection with Fusobacterium necrophorum (Necrobacillosis), with a focus on Lemierre’s syndrome. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20(4):622-59.

- ↑ James A. Coultas, Neena Bodasing, Paul Horrocks, and Anthony Cadwgan, “Lemierre’s Syndrome: Recognising a Typical Presentation of a Rare Condition,” Case Reports in Infectious Diseases, vol. 2015, Article ID 797415, 5 pages, 2015.

- ↑ James A. Coultas, Neena Bodasing, Paul Horrocks, and Anthony Cadwgan, “Lemierre’s Syndrome: Recognising a Typical Presentation of a Rare Condition,” Case Reports in Infectious Diseases, vol. 2015, Article ID 797415, 5 pages, 2015.

- ↑ [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7369198/ Vogel, L. C., and K. M. Boyer. 1980. Metastatic complications of Fusobacterium necrophorum sepsis. Am. J. Dis. Child. 134:356-358. ]

Authored for BIOL 238 Microbiology, taught by Joan Slonczewski, 2016, Kenyon College.