The Increasing Prevalence of Clostridium Difficile in North America

Section

By Aly Palia

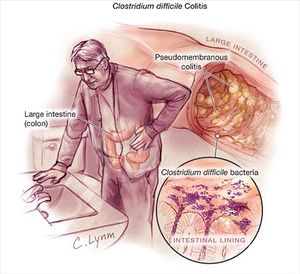

Clostridium difficile infection, or CDI, has become more prevalent through both the United States and Canada in recent years. The infection is spread by spores of the bacteria Clostridium difficile, also known as C. diff. The bacteria themselves are very common in the soil and can be found in the human intestine. In fact, C. difficile exists in around 2-5% of the adult population [1]. When they are in a stressful environment, the bacteria will produce spores that can tolerate more extreme conditions than the bacteria themselves. The bacteria become pathogenic when these spores are produced in the human gut. The spores contain toxins, such as enterotoxin (Clostridium difficile toxin A) and cytotoxin (Clostridium difficile toxin B). Patients with these spores can have diarrhea and inflammation in the body. While the majority of the infections from C. diff can be treated with antibiotics, there are some strains that are increasing in their antibiotic resistance [2]. Thus, many patients with CDIs aren’t able to receive adequate treatment for their infections, so many cases are becoming more severe.

At right is a sample image insertion. It works for any image uploaded anywhere to MicrobeWiki.

The insertion code consists of:

Double brackets: [[

Filename: PHIL_1181_lores.jpg

Thumbnail status: |thumb|

Pixel size: |300px|

Placement on page: |right|

Legend/credit: Electron micrograph of the Ebola Zaire virus. This was the first photo ever taken of the virus, on 10/13/1976. By Dr. F.A. Murphy, now at U.C. Davis, then at the CDC.

Closed double brackets: ]]

Other examples:

Bold

Italic

Subscript: H2O

Superscript: Fe3+

Introduce the topic of your paper. What is your research question? What experiments have addressed your question? Applications for medicine and/or environment?

Sample citations: [3]

[4]

A citation code consists of a hyperlinked reference within "ref" begin and end codes.

Bacteria and Spores

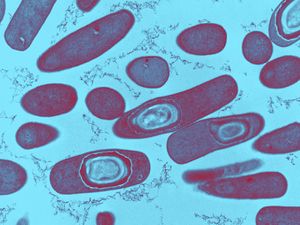

Clostridium difficile is gram-positive, meaning that the thick peptidoglycan layer of the cell wall retain staining. The clostridium family is spore-forming mostly anaerobic bacteria. This also includes Clostridium botulinum and Clostridium tetani (28). They are rod-shaped and motile, although under a microscope they can appear drumstick-shaped because there is a round bulge at their terminal ends (1). They are also anaerobic, although they are able to survive in stressful conditions by producing spores. Because they are anaerobic, they can commonly be found in the oxygen-deficient soil. Spores are formed when the cells are put in conditions that do not allow for typical reproduction and survival. When the environment becomes that unfriendly, the regulators in the cell express genes that function in alternate metabolic pathways to transition from active growth to a stationary phase (8). This involves the creation of a protoplasm that contains a copy of its genetic material. Then, proteins are synthesized into the complexes of the spore. Spores typically take around eight hours to form and are metabolically dormant, so they can remain stable for extended amounts of time. In this state, the spores can sense when there is even a little increase in nutrients in the environment. At that point, the spore then converts back into its typical metabolically-active cell. (7) This conversion can be divided into two different phases: germination and outgrowth (13). Germination is the “irreversible loss of spore-specific characteristics” (16). Germination is triggered by exposure of the spore membrane to different molecules that could serve as resources, such as amino acids and sugars. C. difficile specifically is triggered by bile salts, amino acids, taurocholate, and glycine (20). However, there is still research that is being done to look more into germination in C. difficile because there is a significant amount of diversity within the different isolates (21). Once the receptors in the membrane notice the increase in molecules in the environment, the spore is rehydrated and undergoes cortex hydrolysis (32). After the cortex hydrolysis, there is a release of pyridine-2,6-dicarboxylic acid, or dipicolinic acid (DPA), which lowers the core water content (14). The last stage of germination is coat disassembly, in which the shell of the spore is broken slightly (14). After the whole process of germination, there is outgrowth. During the outgrowth of C. difficile bacteria, the macromolecules are activated in the spore. Then, they are able to leave the shell of the spore and form the fully vegetative cell (14). C. diff spores produce two different toxins to be secreted into out of the cell: toxin A and toxin B. Toxin A is an enterotoxin that creates holes in cells. This makes the contents in cells leak out; in the case of the intestines, the fluid from the cells that line the tract leaks into the intestine itself. This leads to diarrhea as the body tries to dispose of the excess fluid (17). Toxin A is encoded by the tcdA gene within locus PaLoc (19). Toxin B is a cytotoxin that breaks down the cytoskeleton. That causes inflammation and pain for the patient as it impairs the actin cytoskeleton (17). Toxin B is encoded by the tcdB gene within locus PaLoc (19). PaLoc is the 19.6 kB pathogenicity locus that is highly stable in Clostridium difficile (27). While there are three other genes encoded on this locus, these two have been found to be the major virulence factors of C. difficile (19). The toxins also release cytokines from mast cells, macrophages, and epithelial cells. Cytokines are small proteins that affect the specific interactions between cells by acting on the cells that secrete them or the cells that are nearby (20). The cytokines that are released by toxin A and toxin B lead to even more fluid secretion and inflammation in the colon. Toxin A and toxin B are part of the clostridial glucosylating toxin family, because they inactivate Rho and Ras proteins through glucosylation. Glucosylation is the formation of glucoside, which is a molecule of glucose bound to another functional group. These two toxins are both monoglucosyltransferases, so they transfer a glucose molecule onto the Rho family GTPases. GTPases are a family of enzymes that hydrolyze guanosine triphosphate (GTP). They play a role in signal transduction, protein biosynthesis, vesicle transportation, and movement of proteins through the membranes (29). The Rho and Ras GTPases are specifically in charge of controlling cellular functions like the organization of the cytoskeleton and the epithelial barrier function (19). Ras proteins work as molecular switches between an active state that is GTP-bound and an inactive GDP-bound state (30). Mutations in these proteins can lead to cancer and developmental defects (30). Glucosylation by toxin A and toxin B lock the Rho and Ras proteins into a specific conformation into the GDP-bound state that makes them inactive. This stops all signal pathways in the cell that occur downstream of the inactivation. The inactivation will lead to a lack of cytoskeletal organization. When the actin cytoskeleton is disrupted, the cell will undergo apoptosis because the cytoskeleton will not be able to expand to accommodate the resources that are unable to leave the cell (21). Toxin B, while an essential virulence factor in C. difficile , is not as essential as Toxin A (19). Mutant cells with inactive tcdA still produced the same levels of tcdB. However, the mutation with an inactivation of tcdB expressed two or three times more tcdA (19). Additionally, isolated toxin A induces CDI pathology while isolated toxin B did not induce disease pathology unless it was also combined with toxin A (19). The glucosylating family typically has toxins that are between 250 and 300 kDa in size. They can also typically be easily found because they have a high degree of sequence identity (19). Toxin A and toxin B are comprised of three domains. The first is the N-terminal domain; the second is a centrally located translocation domain; and the third is a C-terminal domain. The N-terminus typically start a protein with a free amine group. Messenger RNA is created from the N-terminus; amino acids are then added onto the carbonyl end of the mRNA strand through dehydration reactions until it reaches the C-terminal domain. At that point, there is an amino acid at the end of the mRNA strand that would be looking to bind to the next amino acid. Instead, the C-terminal domain binds a carboxyl group to the amino acid that terminates the amino acid chain (31).

Risk Factors and Transmission

Include some current research, with at least one figure showing data.

Symptoms

Include some current research, with at least one figure showing data.

Treatments

Conclusion

Increasing Prevalence

References

- ↑ Ryan KJ, Ray CG (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. 322-4.

- ↑ [http://www.emedicinehealth.com/clostridium_difficile_c_difficile_c_diff/article_em.htm=PDF Nabili, Siamak N. "Clostridium Difficile." EMedicineHealth. Ed. Melissa Conrad Stoppler and Bhupinder Anand. N.p., 26 June 2016. Web. 17 Apr. 2017.

- ↑ Hodgkin, J. and Partridge, F.A. "Caenorhabditis elegans meets microsporidia: the nematode killers from Paris." 2008. PLoS Biology 6:2634-2637.

- ↑ Bartlett et al.: Oncolytic viruses as therapeutic cancer vaccines. Molecular Cancer 2013 12:103.

Authored for BIOL 238 Microbiology, taught by Joan Slonczewski, 2017, Kenyon College.