The Role of Helicobacter pylori in Gastrointestinal Health

Human Gut Microbiome and Helicobacter pylori's presence

By Alexis Newman

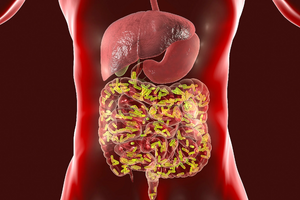

The human gut microbiome is a critical indicator of a person's health because of its profound influence on physiological processes. The number of bacterial cells outnumbers the number of human cells in the gut microbiota, and these microbes play large roles in metabolism and immune function to keep the body alive.[8] The gut microbiome also serves as a barrier against pathogens, preventing their colonization and mitigating the risk of infections. However, disruption in the gut microbiota composition or function can weaken this barrier, increasing the susceptibility to pathogen invasion and potentially leading to gastrointestinal infections.[9]

Helicobacter pylori is a gram-negative, flagella-bearing spiral-shaped proteobacterium1 that can grow in extremely acidic environments, like the stomach. Its "Helico-" name derives from its helical body and because of its shape, the bacteria can make its way through the viscous lining of the stomach with help from stomach enzymes. However, once H. pylori gets colonized in the stomach, its shape can convert from the rod shape to an inactive coccoid shape.[10]

Helicobacter pylori is a class 1 carcinogenic bacteria, 1 being named the most carcinogenic a microbe can be and 4 being non-carcinogenic. H. pylori was determined to be a class 1 carcinogen more than 30 years ago from purely epidemiological data. This investigation showed a positive relationship between gastritis cancer and H. pylori. A couple of years after this phenomenon, in 1991, further evidence showed the prevalence of H. pylori antibodies in patients with gastric and bowel cancer.[11]

Interstingly, H. pylori prevalence is not a problem for all hosts, in fact, some people will go their whole lives with no effects.[12]However, for the 20 - 30% of people who are infected, the consequences can be life-threatening: gastritis (stomach cancer), peptic ulcers, and gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma. Investigation reports state that at least 7 million cases of these listed diseases happen annually, worldwide.[13]

Who is at risk?

In the United States, age emerges as a significant determinant of H. pylori infection, with over half of infected individuals aged 50 and above. Moreover, disparities in genetics and health further exacerbate the prevalence of the infection among African Americans, with around half of Latin American and Eastern European descent also affected by H. pylori.[14]

The risk of H. pylori infection significantly increases when combined with aspirin, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and/or frequent steroid use. These medications compromise the stomach's epithelial barrier, creating a more favorable environment conducive to H. pylori colonization and persistence. Once the bacteria breach this barrier and infiltrate the gastric mucosa, the risk of developing complications like ulcers and long-term gastric cancer escalates.[15]

Research also shows that dietary factors contribute to the prevalence of this infection. Factors such as consumption of meat, chili peppers, unfiltered drinking water and restaurant food put humans at risk[16] as this bacteria can survive in contaminated water and food sources, especially where the pH is ideal at 4.9-6.0.[17]

Life Cycle and Survival Mechanisms of Helicobacter pylori

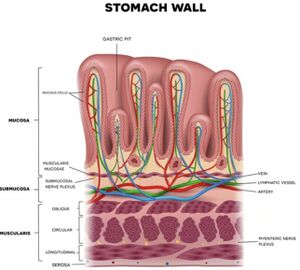

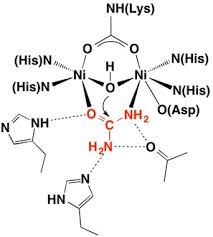

Once H. pylori makes its way into the host successfully, for it to survive and colonize the bacteria needs the means to survive in the highly acidic environment of the stomach. H. pylori secretes urease to neutralize the acidic condition and allow the bacteria to persist in the stomach.[18] The production of urease catalyzes the hydrolysis of urea into ammonia and carbon dioxide. Ammonia acts as a base to neutralize the surrounding pH of the bacteria's space. The neutralizing of this barrier allows H. pylori to use its flagella-mediated motility to adhere to epithelial cells and begin to colonize and infect the host.[19]

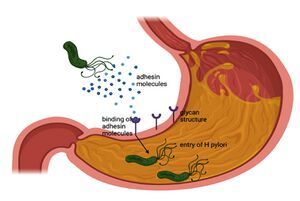

The attachment mechanisms are facilitated by the bacterial adhesions to very specific host cell receptors such as glycan receptors (BabA and SabA), membrane protein (HopZ), the specific luminal side of gastric epithelial cells (CD74), and Decay Accelerating Factor (DAF and CD55) receptors. Additionally, H. pylori can bind to sulfated molecules like herapan sulfate found on the surface of the epithelium. [20]

This immune response results in a congregation of neutrophils along with macrophages and lymphocytes all in an effort to rid the pathogen's survival and infection; however, this often does more harm than good to the host. The build-up of these immune cells causes tissue damage that creates gastric ulcers and/or more severe gastrointestinal infections.[21]

As mentioned previously, Helicobacter pylori is a successful pathogen that has colonized more than half of the human population. A valid question some might ask is how this pathogen does not infect everyone, while some immune response mechanisms do work effectively, H. pylori has evolved to overcome the host defense mechanisms.

Firstly, H. pylori has modified its surface, lipopolysaccharide, and flagellin to evade detection by host pattern recognition receptors, for example, the tolllike receptors. This makes the bacteria mimic the host structure and ultimately avoids triggering the host's immune system. [22]

H. pylori also avoids phagocytic death by killing the macrophage before it can commit phagocytosis uptake. H. pylori does this by resisting fusion and disrupting the production of reactive oxygen species and nitric oxide from phagocytes making the bacteria free from phagocytic death and survival within the host. [23]

Another way H. pylori has adapted to thrive and overcome the host's defensive mechanisms is the induction of apoptosis in gastric epithelial cells. In processes like upregulating the apoptotic pathways, this allows for increased permeability of the gastric mucosa and facilitate the entry of the bacteria into the underlying tissue. This specific path means that the bacteria is secreting its toxic enzymes into the body and degrading tissue. This tissue degradation can be short-lived, acute, and resolved to be only a peptic ulcer. Should this inflammation persist over long periods and continue to degrade the mucosa tissue, gastritis is in full effect. [24]

Symptoms and Detection of Helicobacter pylori Infection

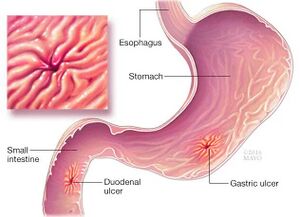

The first internal sign of gastritis is the formation of a peptic ulcer in the stomach or the duodenum area, the small intestine of the stomach. Peptic ulcers often cause symptoms of indigestion and this can be coupled with pain and discomfort in areas between the belly button and breastbone, this pain is the most common symptom of peptic ulcers. Other related symptoms are: feeling full too soon while eating, nausea, vomiting, bloating, and belching. However, these symptoms are no means of direct correlation between the two. [25]

Escalated symptoms that differ from other infections such as black or tarry stool or red and morron blood mixed with stool, red blood in vomit that looks like coffee grounds, sudden or sharp abdominal pain, and dizziness could be caused by H. pylori. These symptoms are obvious signs of peptic ulcers and should be brought to professional attention immediately to obscure the infection. [26]

Gastritis is the escalated scale of inflammation as it is the chronic and persistent degradation of tissue in the stomach lining. This has the more severe and long-lasting symptoms listed above, with the addition of weight loss and loss of appetite. [27]

With the evolution of science, there are now two frequently run stool tests employed to determine if Helicobacter pylori has infected the human body. The first is a stool antigen test, which looks through the stool for the antigens that are associated with H. pylori infection. The second is a stool PCR test. This test is especially useful to determine if there are mutations that could identify the presence of the pathogen as well as if the pathogen has mutations that might be antibiotic-resistant to prescriptions. [28]

Other tests like breath test can be used to quantify the release of carbon dioxide from the body. This test is effective because if H. pylori has colonized, the pill that is swallowed for the test can tag carbon molecules that were in contact with the bacteria and detected by special devices. This is incredibly useful for younger children who are unable to cooperate with a scope screening. Some professionals opt for a scope test that uses a tiny camera on a flexible tube, an endoscope, which can move from the throat to the duodenum to manually and visually search for the infection. [29]

Antibitoics and Remedies

The insertion code consists of:

Double brackets: [[

Filename: Paeruginosa.webp

Thumbnail status: |thumb|

Pixel size: |300px|

Placement on page: |right|

Legend/credit: Magnified 20,000X, this colorized scanning electron micrograph (SEM) depicts a grouping of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bacteria. Photo credit: CDC. Every image requires a link to the source.

Closed double brackets: ]]

Other examples:

Bold

Italic

Subscript: H2O

Superscript: Fe3+

Sample citations: [1]

[2]

A citation code consists of a hyperlinked reference within "ref" begin and end codes.

To repeat the citation for other statements, the reference needs to have a names: "<ref name=aa>"

The repeated citation works like this, with a forward slash.[1]