Cryptosporidium

|

NCBI: |

|

|

Classification

Higher order taxa:

Species:

Cryptosporidium parvum, C. andersoni, C. baileyi Description and Significance

|

|

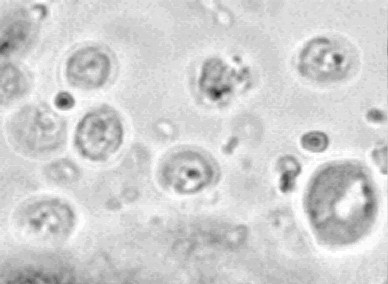

The life cycle of Cryptosporidium begins as the host ingests the parasite in its infective stage, the oocyst. Inside the host the oocyst releases four sporozoites, which move into the intestine and take up residence within the host's epithelial cells. Two asexual cycles take place, resulting in the production of meronts. First generation meronts contain eight merozoites; second generation meronts contain four merozoites. This second generation of merozoites invade other cells and develop into either female or male gametes. The male gametes break out of the host cells and fertilize female gametes in other cells. The fertilized female gametes morph into oocysts and in turn break out of the host cells. Two kinds of oocysts are produced: a thin-walled type which stays inside the host and continues replication and infection, and a thick-walled type which is excreted in the host's fecal matter. During these processes the host cells are destroyed, putting the immune system into action and causing many of the clinical symptoms of gastrointestinal disease. The oocysts are generally small spheres, 4-5 micrometers in diameter, and are highly resilient against chemicals and outside environment factors. |

Ecology

As Cryptosporidium is primarily contracted through drinking water, the prevention and control of this parasite has become a public health concern. Various government committees and associations are at work to regulate the decontamination of both public and private water sources. Prevention methods include the installation of more advanced filtration systems, constant testing of water supply, and educating populations about the signs of the disease and ways to prevent it. The distribution of Cryptosporidium is worldwide, but outbreaks are especially common in developing countries and those with high rates of AIDS among the population. {| width="100%"

References

Atwill, Rob. Cryptosporidium parvum and Cattle: Implications for Public Health and Land Use Restrictions. Medical Ecology and Environmental Animal Health, University of California-Davis.

Cryptosporidium.Animal Waste Pathogen Laboratory, U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Cryptosporidium Infection Fact Sheet. Division of Parasitic Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Khan, Omar A. Cryptosporidium parvum. Atlas of Medical Parasitology, Carlo Denegri Foundation.

Upton, Steve J. Cryptosporidium Research. Division of Biology, Kansas State University.

What Water Utilities Can Do to Minimize Public Exposure to Cryptosporidium in Drinking Water. Government Affairs, American Water Works Association. 2005.